A New Collection of Lenape Folklore

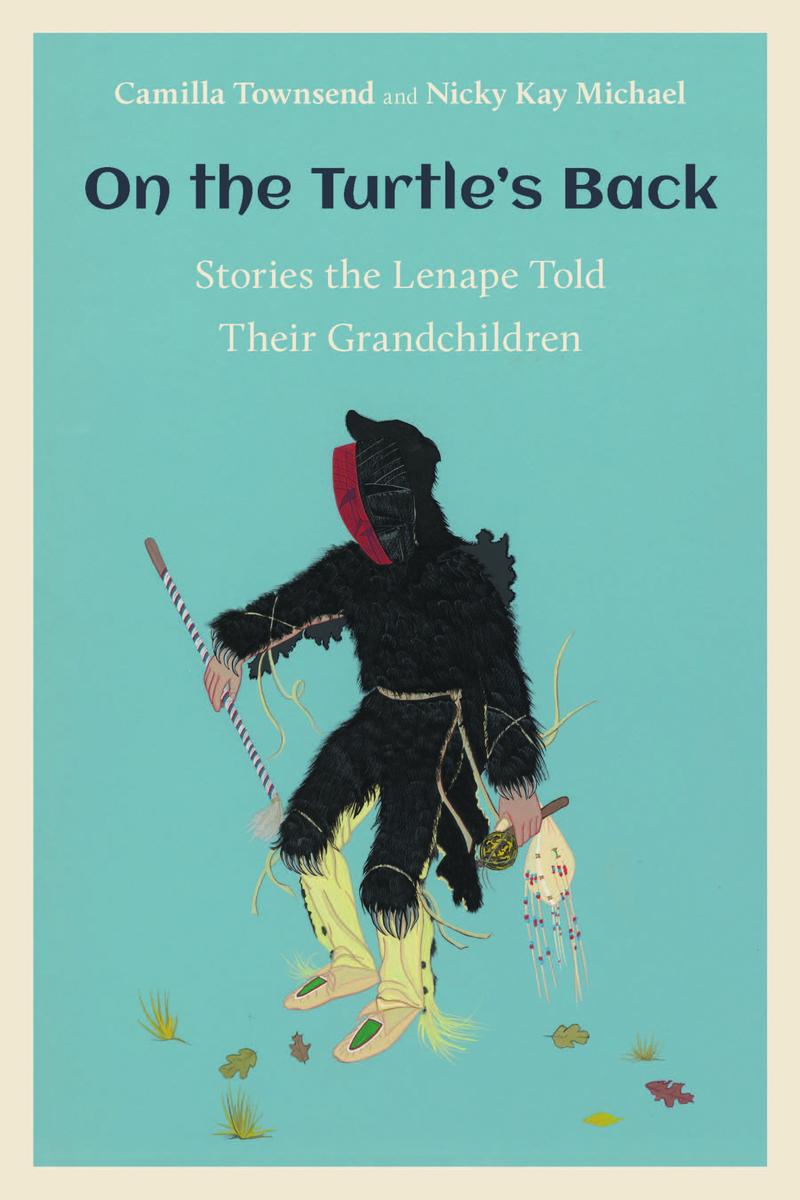

( Courtesy of Rutgers University Press )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Indigenous Peoples' Day is on the horizon, and this Monday, one of our next guests will take part in New York City's Indigenous Peoples' Day Open House at the National Museum of the American Indian.

Editors Camilla Townsend joins us, along with Nicky Kay Michael, to discuss the very first collection of Lenape folklore, which was gathered more than a hundred years ago, but not published until now. It's titled On the Turtle's Back: Stories the Lenape Told Their Grandchildren. Originally compiled by an anthropologist named M.R. Harrington. It includes stories about the world's creation, epic heroes. The Lenape, also known as the Delaware Nation, carried with them from their ancestral homelands. The editors of the collection join us now. Camilla Townsend is a professor of history at Rutgers University, New Brunswick. Camilla, nice to meet you.

Camilla Townsend: Very glad to be here.

Alison Stewart: Also joining us is Delaware Tribal Council member Nicky Kay Michael, who is the interim president of Bacone College in Oklahoma, where also she's the executive director of the Indigenous Studies and Curriculum. Nicky, welcome.

Nicky Kay Michael: Nèmi Lowááneen. Thank you. I'm glad to be here.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, we'd like for you to join the conversation. Native American listeners, what stories did you hear growing up? If you have children, how often do you tell those stories to them? Non-native listeners, what kinds of folklore beliefs are passed down in your culture? Why do you think those stories are so important to pass down? Give us a call or send us a text. The number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. Or you can reach out on social media, the handle is @AllOfItWNYC.

Nicky, if you grew up in New York or New Jersey, like I did, you learned about the Lenape people as a kid, but of course, we know history books of your don't always get it right and get the nuance right. Who are the Lenape, Nicky?

Nicky Kay Michael: We are an Indigenous group known as "the Grandfathers," and we originated in the East Coast of the United States. Our stories go back to the origins of being on this continent. The United States would be part of the turtle, and that's the metaphor of the turtle in the stories, and as the Grandfathers were the oldest Algonquin-speaking tribal nation, and there are many other Algonquins that consider us Grandfathers, and they came from our people and moved westward, but it wasn't until after the colonial settlement that my people, our ancestors, were removed 8 to 10 times before we got to Oklahoma.

From Oklahoma, there are two of us, Delaware Nation in Anadarko and Delaware Tribe of Indians in Bartlesville, and as the main bodies, we are the ones that have retained and continue to practice our traditional ways.

Alison Stewart: Camilla, a lot of these stories were compiled over a century ago by an anthropologist named M.R. Harrington. Who was M.R. Harrington?

Camilla Townsend: M.R. Harrington was actually born in Michigan, but he grew up in this area, in the New York City area, and ended up working for a man who was starting to found a museum of Native American artifacts, as they used to say, and he sent Harrington out west to Oklahoma because they knew that the Lenape, the Delaware, were by then living out in Oklahoma. He wanted him to buy their ancestral valuable and even sacred goods to bring to the museum, and we may wince at that. It's not what we would want somebody to be doing, but M.R. Harrington turned out to be a relatively interesting guy.

He sat with many different people, but especially two men, Charlie Elkhair and Julius Fouts, and their wives, two Delaware guys living in Bartlesville, and they told him stories, and he wrote them down. Then they started to dictate their stories to their children, who read and wrote in English, and they mailed more stories to Harrington after he got back home to the New York City area, and they really wanted him to publish these stories. We tend to think it's all about the anthropologist going out there and collecting the materials or collecting the stories, but Nicky said to me when I first met her, "I bet it was the Indians who wanted this done."

When I went to the UPenn Museum archive a couple years ago and found Harrington's correspondence, it became very clear that Julius Fouts, especially, was writing to him constantly saying, "When is the book going to come out? Come on, come on. We gave you the stories. Come on already." Unfortunately, Harrington's wife died, and he had a lot of problems, ended up leaving the museum and the book never did come out, but now, thanks largely to the effort of Nicky and her fellow tribal members, we are getting this book out so that the world can see these stories as they were told and written down then when the language was still vibrant and the stories were still well remembered.

Alison Stewart: Nicky, why did you know that the push for this was coming from the native folks?

Nicky Kay Michael: Well, a lot of it has to do with owning our own voice, and that voice needed to come through. They'd been through trauma after trauma after trauma of being in a new territory, and our stories are not just that. There's different categories of our traditional stories, whether it's our tribe or a different tribe, but those tell so much about who we are and what our values are, and they most likely wanted them out because they wanted to have that equal playing field.

Alison Stewart: My guests are Camilla Townsend and Nicky Kay Michael. We're talking about On the Turtle's Back: Stories the Lenape Told Their Grandchildren. Let's talk about the turtle's back on page 35. A number of Indigenous tribes share the story of a woman falling from the sky and landing on a turtle's back, on which the animals and the birds place enough soil so it gradually becomes earth. Camilla, I think you're going to read two versions of this for us?

Camilla Townsend: Two little mini versions that were told by Charlie Elkhair and Julius Fouts when Harrington asked them about the creation. They clearly knew longer versions, but they were giving him mini versions. Here we go. "The earth was created once (by Gicelemu'kaong)," and we'll have Nicky correct my pronunciation later. "He then covered it with water afterward. There was trouble in getting dirt to start a new earth. Various animals were sent down to get dirt, but they all came up drowned. The Muskrat finally got dirt in his paws, but he was dead too when he came up. Whoever was fixing the new earth--perhaps it was God--took this dirt, and after inquiring which creature was able to hold it, he put the dirt on the Turtle's back, and at once it began to grow, until it became the great Island we live on today."

Another day one of them told this story. "When Someone created the animals, he asked, 'Who can carry the earth on his back?' And da-gosh, the turtle said, 'I can!' So the creator put the dirt on his back and made it grow, and it became the earth.

About the same time, he asked, 'Who shall be the deer?' And the Rabbit said, 'I will.' 'Well,' said the creator, 'just run round and we'll see.' So the Rabbit ran by, and one of the Indians was told to shoot it. So he did, and he hit it with an arrow, and the rabbit squealed out loud. When he was done squealing, the creator said, 'Well, you cannot be the deer. You would make the Indians ashamed with your squealing whenever they hit you.' So he appointed deer to be the deer."

You can see they were perfectly willing to tell a joke, and at other moments, perfectly willing to be serious.

Alison Stewart: Nicky, why is this a common origin story among tribes of the Northeastern Woodlands?

Nicky Kay Michael: Well, that's a question above my pay grade.

[laughter]

I can't say why for sure. I just know that they are, and typically, again, as the Grandfather tribe, if all the tribes came from, or at least a majority of the Algonquin tribes came from us, of course, as they move west, the story is going to morph into something more fitting of where they're at ecologically, but I think that's the reason that it can come back to us is because we were the regional speakers.

The other part of that some of the tribes say, for instance, the Southeastern groups, like the Cherokees and the Muscogee, share our story because we were in the same place, and people tend to think that we didn't connect with each other, but there were a lot of shared dances and language and ways. I suspect that we were also sharing those same stories.

Alison Stewart: We have a few questions from listeners. Jane is calling in from the Bronx. Jane, thank you for calling in. You're on the air.

Jane: Okay, good afternoon, everybody. I appreciate this segment, really helpful. I have a question somewhat related, I hope, about land acknowledgements, and I'm sure or I imagine people are familiar with this. There's now a proliferation of land acknowledgments that we hear at the start of conferences and gatherings. To me, and I don't know a lot about this, it seems some are superficial and facile, and others seem to really help support the people at the gathering to think more deeply about place and where they are, and what a time would be like before Western colonization and genocide, et cetera, et cetera, and put people a little bit more deeply thinking about these things.

My question is, what do you think about land acknowledgments, and are there ways to make them better, deeper, different, more meaningful, or maybe you think the whole thing should be scrapped, and it's just not helpful? That's my question.

Alison Stewart: Oh, thank you, Jane, for the question. Nicky, would you like to take that?

Nicky Kay Michael: Oh, this is a loaded question [chuckles], and a really good one at that, especially from New York and New Jersey area. I think they're good. I think that everybody needs to have land acknowledgments, and if there are insincerity, then of course, I think they're important for others to understand that the Indigenous folks that were on that particular place or space or area was considered a nation and that basically anybody else is occupying it. In that regard, we want to make sure that that is a valid and meaningful start to many of the meetings. However, and completely in agreeing, some of the land acknowledgments are, oh, it's just bad as the thing to do rather than understanding the depth of what is taking place.

There are many stories I can give about what that means, but I can give you also a couple of scenarios to think about. We have a number of colleges, universities, historical organizations, especially in New York, that are making these, and if they connect with our tribes, so let's say for instance some of them go to the Munsee, the Mohican group that's in Wisconsin, or they'll come to us, and they will define and come up with a land acknowledgment that includes our voices, and that's wonderful. The other part of this, though, is why are we doing them if we're not also acknowledging that the land is stolen?

That Delawares, we would love to go back to our homelands. We would love to go back and be able to gather the wampum in, and we start over again and developing and renewing those cultures and dances that we had in those areas, but it's a long time ago, and it's a lot of work to recreate those. Those bridges have to be redone again, and I think that land acknowledgment should also include that. If there's no land back, there's really a kind of superficiality to it.

I also want to encourage, especially colleges and universities, to think about some of this especially back East where you have a handful of native peoples going into your college, and you're trying to start an Indigenous Studies program, while many of us in Oklahoma are just struggling. We have the Native students, but because they're in the East and they're on the traditional homelands, they are getting the funding that is not coming to us.

I just want to encourage folks to think about what that really means when we're acknowledging. Do we put land back into it? Do we put money and investment into it? Because we're still perpetuating the same situation, and marginalizing our native folks, only we're doing it now in a way that says, "Oh, hey, we're acknowledging you. Look, we've got the money to build an Indigenous Studies program but you don't have access to it."

Alison Stewart: Thank you for that thoughtful response. That was Nicky Kay Michael, the interim president of Bacone College in Oklahoma, where she's also the executive director of Indigenous Studies and Curriculum. Camilla Townsend is professor of history at Rutgers University, New Brunswick. We are talking about On the Turtle's Back: Stories the Lenape Told Their Grandchildren.

We got this great text. I want to read it real quick. I grew up in Iowa, and I am Muslim, but hearing the stories of human origin, I was in awe that they are as similar to ideas as an Islam, and that was a really powerful point of relation for me personally. Stories and traditions are so important to maintain within a culture and have a powerful way of resonating with people of all kinds outside of that culture, and showing that there are so many ways to approach the world, not just the post-enlightenment way we have been heavily influenced to accept in modern times. Thank you for that text.

Camilla, I mentioned we talked about the origin story. There are stories about heroes in On the Turtle's Back, what's important to know or what’s something you would like people to know about some of the heroes that they might encounter in this book and in these stories?

Camilla Townsend: That's a great question. I was really struck when we were working on editing the stories that, in general, the heroes are not like they are in Western myths and Western legends, that is, they're not fantastic, charismatic, buff guys, who always win whatever it is they set out to win, not at all. They tend to be rather ordinary folks who are doing their best to get along, and learning a lot as they go about it. There's one character that turns up in a number of Lenape stories, where he is often translated as a strong man who has an Amelia Bedelia-like characteristic of taking things very literally, not knowing, not recognizing the context, and then making mistakes.

There's another wonderful story about a boy who is abandoned. He's an orphan, and he's abandoned by his people, and bears find him and raise him. Later, he goes back to live with humans, but rather than being grateful and having learned all that he showed from his time with the bears, he uses the knowledge that he has of their lives to lead people in hunting them, and behaving other abusively towards them, but the bears have the last laugh, so to speak. That is, they track him down and teach them some lessons, and I won't give away what it is. It's very funny and very effective.

I love the idea that for them a hero is someone who's learning, who's going through life and figuring things out, and learning sometimes that he's wrong, and thus, in the end, I would say being stronger and wiser and better.

Alison Stewart: Nicky, what is the story that you'd like to tell people about in our last few minutes?

Nicky Kay Michael: [laughs] Oh, my goodness. Actually, I wanted to share one from some of our elders about how she learned to cook frybread, and it's actually not in the book, but we put it in our elders' interviews, at least a select few that we could put in there. I went to different elders in the ‘90s and asked them questions, and oftentimes, that I didn't even need to ask them they would just start talking, and I would just let them flow.

One of them, Aljie Brian, she said that she learned to cook frybread, and as some of you know, frybread has turned into one of our staples here in the country. It's literally bread that's fried, and it comes from the commodities that they used to give our ancestors in lieu of them being able to hunt. She said that when she first learned to cook frybread, she was terrible. [chuckles] She said, "My dog wouldn't even eat it."

[laughter]

That's really funny because if you can't cook frybread in any country, there's a problem. She said her brother ended up in the hospital, and he just looked at her and he said, "Aljie, I want frybread for my last meal," and she was like, "No pressure." She went back home and started cooking frybread, and she finally got it right. She took it to her brother, and before he passed, he said it was the best frybread that he'd ever eaten. Well, it was a really moving point, and from that day forward, whenever she cooked, she would always when she would pray, pray of course to the ancestors, and ask were a good result in frybread when she cooked it. To me, that's exactly why-- [crosstalk]

Alison Stewart: I’m loving the story. I want to make sure I get the name of the book in one more time before we have to wrap. It's called On the Turtle's Back: Stories the Lenape Told Their Grandchildren. I've been speaking with Camilla Townsend and Nicky Kay Michael. Thank you so much for sharing these stories with us.

Camilla Townsend: Thank you.

Nicky Kay Michael: Thank you.

Alison Stewart: There's more All Of It right after the news.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.