A New Book Celebrating Female Philosophers

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. In honor of Women's History Month, we're going to take the opportunity to wax philosophical about some influential thinkers from the male dominated-world of academic philosophy. The same world whose most famous name said things like she, the proverbial woman has the capacity for understanding, but her capacity is weak. That was Thomas Aquinas.

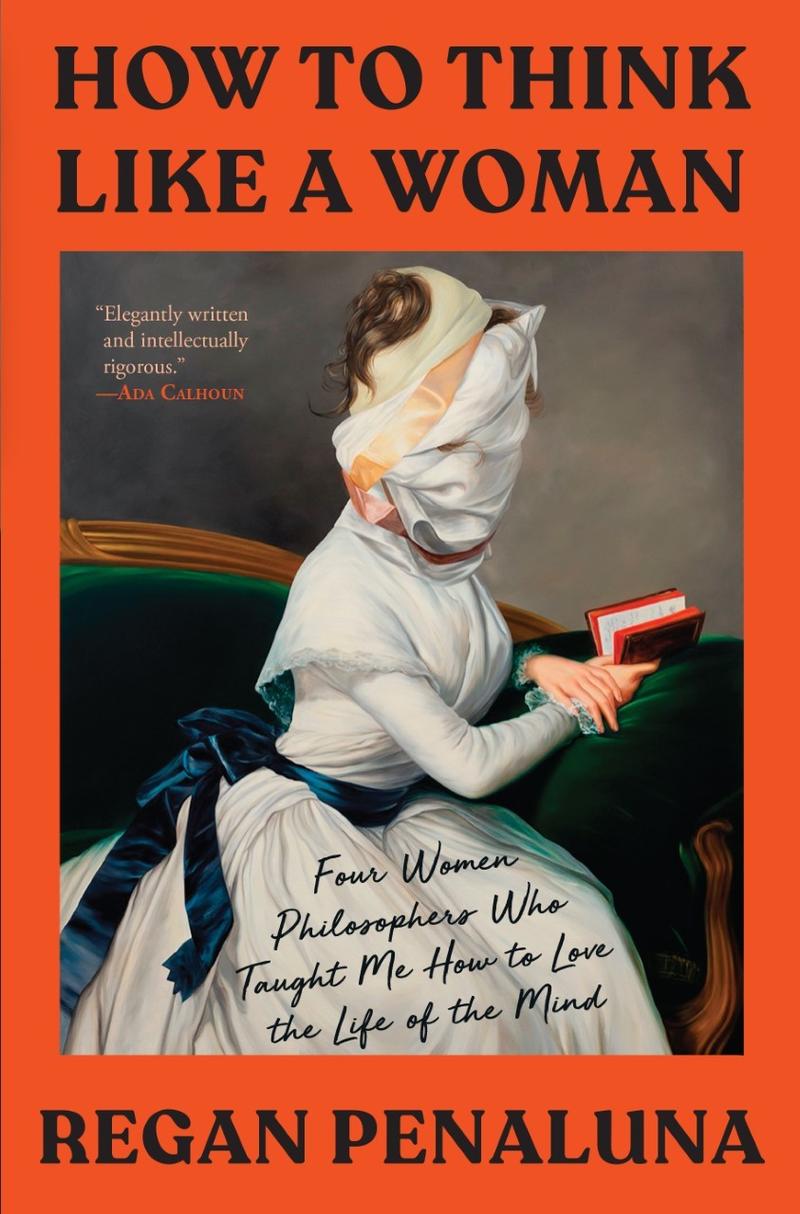

To women, silence is a crowning glory from Aristotle. Troubling things they hear from guys whose ideas shape society as much as they do. More troubling still if you're a graduate philosophy student who happens to be a woman, as my next guest was. Her name is Regan Penaluna, and her new book is called How to Think Like a Woman: Four Women Philosophers Who Taught Me How to Love The Life of the Mind. It comes out tomorrow.

Its chapters flow between the story of Regan's academic career and personal relationships through gatekeeping professors in self-doubt and outright misogyny to a survey of how some of the field's favorites Plato, Aristotle, Bacon, treated the women in their lives to a celebration of the lives of four philosophers, Mary Astell, Damaris Masham, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Catharine Cockburn. It's a Cockburn or Copper?

Regan: It's Cockburn.

Alison: Thank you. We'll get to talk all about that with Regan Penaluma. Reagan, welcome to the studio.

Regan: Thanks, Allison. It's great to be here.

Alison: You mentioned that when you were defending your dissertation, your professors gave you props for being the first doctoral student in the department's history to focus research on women philosophers. First of all, that must have blown your mind as being the first. How did that academic work inform the ground you cover in the book?

Regan: That did floor me. At the same time, I had never studied a woman philosopher in any class. I hadn't taken any feminist philosophy courses. I knew what I was getting into. My dissertation covered three of the four figures you mentioned and they formed the bedrock for this book. I completed my PhD. I went on to teach philosophy and I never forgot them even after I left academia. I wanted to tell their story because we don't often hear the story of women in philosophy. It's the field that's known to be the field of dead white men, but, actually, there were women in the early enlightenment, which is the period I studied, and there have been women from the very beginning.

Alison: It's interesting you talk about-- I'm going to get to the woman very shortly, but the idea of the woman question, the woman question comes up over and over again. Male philosophers weighing in on the woman question. First of all, what is the question exactly?

Regan: Good question. It's a question that comes up from the dawn of philosophy is philosophers are very much interested in the human condition. What is it to live a good life? What is it to be a member of society? Often, this question is framed in a way that is specific to the men doing the philosophy, to white men. Other questions, such as who are these other people over here, these women? Are considered to be a unique question, let's call it the woman question. It's something that I found didn't bring me into philosophy, but once I was there, I realized I couldn't stop thinking about it because it's treated as a marginal question, which seems so strange. To be a woman is to be a human, and it should be part of the larger questions that we ask in philosophy.

Alison: Although you write in the book, as I was reading through it, it's always the man's opinion of the woman. Is the answer to the woman's question. [laughs].

Regan: Yes. Right. This has to do with the history of philosophy as it's taught. We learned that the greatest philosopher of all time are Plato, Aristotle, René Descartes, John Locke, Immanuel Kant. These guys, it also turns out didn't have very pleasant things to say about women. They set the discourse. The truth is, though, there were women responding to these thinkers and defending women. There are also men doing the same thing but we don't hear about them.

Alison: My guess is Reagan Panaluna, the name of the book is How to Think Like a Woman: Four Women Philosophers Who Taught Me How to Love The Life of the Mind. Let's talk about some of the philosophers, Marry Astell, born in 1666. How did she buck the expectations of the time for women living? She was in England, right?

Regan: She was. All four these thinkers that I focus on are British. There is a chapter where I run through the history of philosophy. I talk about women from all over the world. These four were British. Mary Astell grew up in New Castle in northern England, and she was an incredible person. She was brought up in a coal mining family and as gentry, so she was well-to-do, but it just turned out that the mines were running low.

Her father lost a lot of money and the family was in debt. By the age 12, her father died. She realized she had no dowry, which meant that if she would marry, which, of course, she would marry, she's a woman, she would have to marry below her. What this meant, too, was that she would have to give up the studies that she was undertaking with her, uncle, Ralph Astel, who was a philosopher, hence studied at Cambridge University.

This was a bleak future for her. To marry someone below her station would most likely mean she would be left to do drudgery. Her teenage years were very melancholic. She didn't want to participate in parties. She writes about this in poetry. She found it all terrible doing makeup and dresses. She decided that around her early 20s, that she was going to buck tradition, as you said. She left New Castle and took a carriage south to London, a two-week journey at that time. Took a risk to try to make it as a philosopher. No woman had ever done this at the time. There was a woman who made a living writing, Aphra Behn, and there were a few women doing philosophy but they were aristocrats.

If their works didn't sell, it wasn't a problem. Mary Astell took a big risk, and it was tough that first year but the risk paid off. She became a very well-known woman philosopher of her age.

Alison: What about her work or her way of thought has-- Why does it have staying power? What about her work?

Regan: Mary Astell spoke to me, first, as a graduate student when I came across her work. Her book that spoke to me is titled A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, and I loved that title. No other title in early modern philosophy spoke to me like that. The titles of the book are Meditations on Philosophy, The Search After Truth, Ethics, and then there was A Serious Proposal to the Ladies.

Alison: Love that. [laughs].

Regan: In this book, she addresses the sexism and misogyny that a woman confronts a woman who wants to think. She wants to provide a remedy for this. Her solution is for women to come together and form an intellectual community, one that is protected from that misogyny and sexism they find because no men are allowed. It, essentially, is a first proposal for a first female college.

This idea in graduate school was a revelatory, the importance of finding those people who make you feel like you belong so that when you are working through ideas and taking risks, you feel that support, which is something that I didn't feel as a graduate student in a male-dominated world.

Alison: Damaris Masham, tell us a little more about Damaris Masham.

Regan: Damaris. She lived a very different life from Mary Astell. She was born and raised on the grounds of Cambridge University. Her father was Ralph Cudworth, a famous philosopher at the time, although we don't know about him because he had a very strange philosophy. She studied philosophy from a young age and most likely from her father. Although she does talk about how she was discouraged from it, but we don't know why that was.

She eventually met the most famous philosopher of the time, John Locke, who inspired the founders of the US Constitution with this theory of inalienable rights. She met him, over twice her age. She's a hot, smart young woman. They met at a party. He was turned on and he wrote her a letter. It kicked off this long, almost 20-year correspondence between the two.

Alison: How would that correspondence have been viewed at the time?

Regan: It wasn't unusual for older men to court young women. John Locke, he also was not interested though in a serious relationship, and this was partly because at that time, to be an intellectual, as a man, was to be chaste. There was a theory that too much ejaculation actually robs you of your reason. John Locke was not interested in engaging in marriage, although he did have flirtations with other women. This relationship was not unusual.

Alison: What did Damaris want to explore? What did she want to think about?

Regan: Damaris, she was intimately familiar with theories of knowledge and metaphysics of her time, she knew her father's philosophy inside and out and explain that to John Locke and to live nets and other contemporary philosopher. What got Damaris into philosophy, what made her take that risk because it was a risk for a woman to do philosophy, a woman doing philosophy was considered monstrous.

She was looked down upon as if she's stepping outside of what is expected of her.

What drew her to it was-- many years later, after she was married, and she didn't marry John Locke, she married someone else and had children, but it was motherhood. It was thinking about what it is to be a mother and she wrote about the dignity of motherhood at a time when mothers were being disparaged and blamed for perpetuating sin in the world.

Alison: [unintelligible 00:11:53], you mentioned risk and stepping outside of the prescribed roles. If you stepped outside the role, were you allowed to come back into the fold, or was it one of those situations where if you step out, if you take this risk, there's a chance you cannot come back into society, or what society says you should be doing or behaving?

Regan: I just think that depends on a case-by-case situation, Masham took this risk. It's not clear, I don't think her work was that popular. Not many people discussed it. A friend of hers translated into French and that's about all we know. Mary Astell, on the other hand, was very well known, very controversial. She was called a monster. I think it was tough, but by the time all of her works are coming out, she had a really good support network with some women. I think she could manage that.

Alison: My guest is Regan Penaluna, the name of the book is How to Think Like a Woman, it comes out tomorrow. Mary Wollstonecraft, you write in her book, Rights of Women, that what she wrote about male philosophers was racy and delightfully out of place among the niceties of academia. Why did she lean into that tone? Why was that her route to philosophy?

Regan: I love Mary Wollstonecraft. She kind of met the things that men were saying about women, the way that, frankly, philosophers treated the woman question as a special question and is separate from your nature. As this was discussed, how can this be? How come you aren't treating women as equals, right? Her favorite philosopher was Jean-Jacques Rousseau. She looks a lot to his theory of education, his moral psychology in his claim that freedom is the goal of human life. The thing is, though, is we're so really only extended that to men, and that she just found it incredibly upsetting, and so she extends it to women too.

Alison: This is a great line that she writes, men indeed appear to me to act in a very unphilosophical manner when they try to secure the good conduct of women by attempting to keep them always in a state of childhood.

Regan: Yes. Then they're in a state of childhood because they haven't been allowed to reason. They haven't been allowed to cultivate their intellects. This is something that I found really fascinating but Wollstonecraft, too, is she describes women as capable of so much but they have been conditioned to be and she says this, "Like a dog, spaniel like," to please men just as dogs are so good at pleasing humans.

She found that, she was so disturbed she found that in herself. She fell in love with a man, an American, Gilbert Imlay. When she found out he cheated on her, she attempted suicide, and then when she found out he did it again and she attempted again. She was so conflicted in herself that a part of her was so susceptible to being the conditioned weak woman. Then there was this other part of her with this feminist imagination who had great ideals for womankind.

Alison: Catharine Cockburn began as a playwright for women on stage. How did theatre and expression through theater fold into her work as a philosopher?

Regan: She started off writing plays. These plays, she saw as instructive, and this goes back to Aristotle's idea of drama as really a way to change and the sentiments of those who are watching. She used her plays as a vehicle to convince people that women deserve freedom of conscience that we have to care for them. What happened is that she and these couple of other female playwrights who were relatively successful also took quite a bit of battering.

There was a play written called Female Wits, which really disparaged these three, and so, eventually, they all left playwriting behind it, it was a tough field. They were made fun of, they were called prostitutes, they were called idiots, all these awful things. Cockburn retired to the country and realize that if she is going to get this message across about women's right to freedom of conscience, she's probably going to have to choose something else, something that people will take her, hopefully, a little more seriously, and which she can provide a more firm foundation for, and so this began her turn to philosophy.

Alison: For you, you left academia, what made you want to leave? Start with that. What made you want to leave, let's leave it there.

Regan: It's a complicated answer. I turned to journalism and into writing for a general audience. Part of it is what I found when I left, and I left because I fell in love, and my husband's in New York City. It's very difficult as an academic to find a job where you want to live and I was in a four-year contract position. The short answer that is simply convenience and for family. Also, I began to see the questions that I was asking and the ways I wanted to think about these philosophers, and about these four in particular, I really wanted to lean into their female subjectivity and telling their life stories and understanding them in a way that, I think, started to bleed outside of academia and made more sense as a writer.

Alison: The name of the book is How to Think Like a Woman: Four Women Philosophers Who Taught Me How to Love the Life of the Mind. I want to let you know that Regan Penaluna will be at the Cobble Hills, Books Are Magic tomorrow at 7:00 PM with Ada Calhoun, want to make sure I got that in there. Thank you so much for coming to the studio today.

Regan: Thank you so much.

Alison: There's more All Of It on the way. Stay with us.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.