A New Biography of Our Unofficial First Female President

[music]

Alison: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart. Thanks for spending part of your day with us. Whether you're listening on the radio, live streaming, or on demand, I'm grateful you are here. On today's show, we'll hear some music from singer Yazmin Lacey, who just released her debut album, Voice Notes. We'll talk to Triangle of Sadness Director Ruben Östlund, and we'll talk about why 1993 was a big year for Steven Spielberg and take your calls. That is all in the way. Let's get this Feminist Friday started with a look at a surprising life of a surprising First Lady.

[music]

Alison: A new biography reframes the legacy of a woman who for a time was practically if unofficially and unconstitutionally the first female president of the United States, Edith Wilson. After a good deal of dating on the down low, President Woodrow Wilson wed Edith Bolling Galt in 1915 while he was in office. It was a second marriage for both. The public embraced the tall, elegant, youngish smart woman as First Lady. When Woodrow Wilson suffered a stroke during his second term, she was there for him. Boy was she there for him. Wilson's Health weakened to the point that he could hardly leave his bed, let alone carry out his presidential duties.

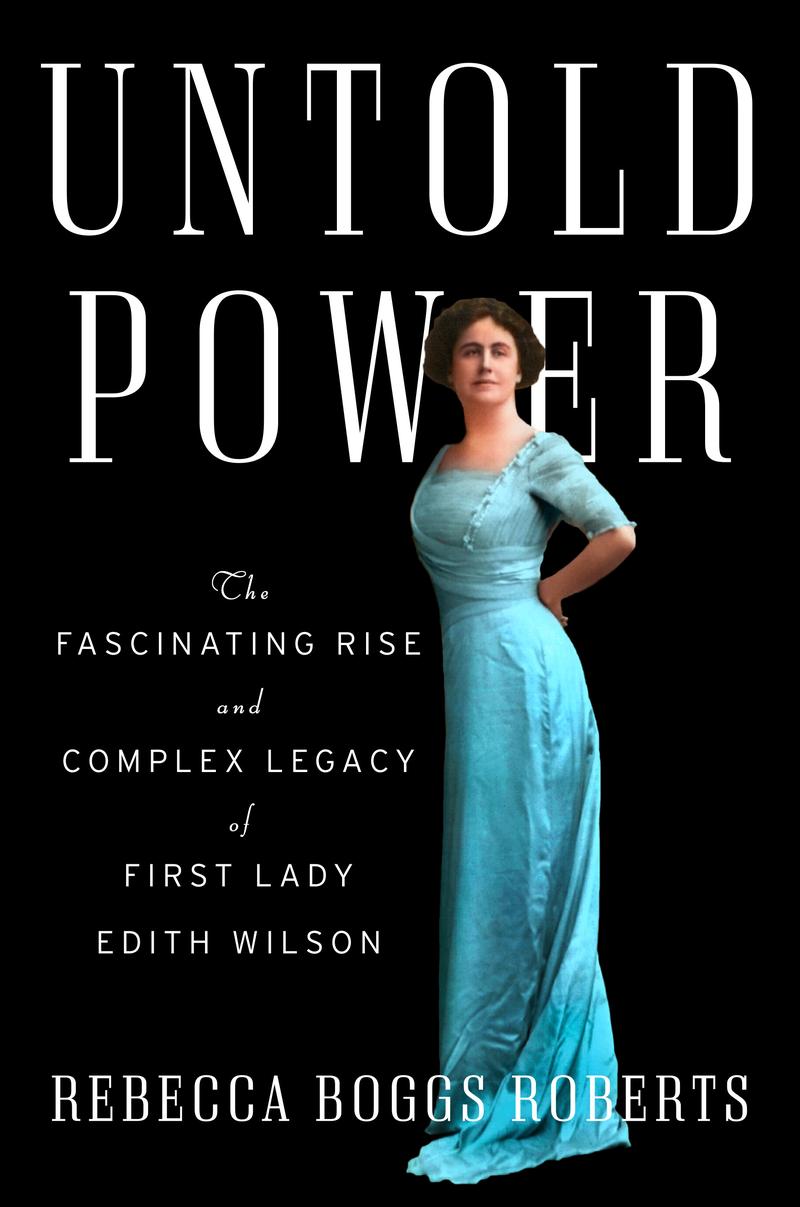

During the last year of his presidency, responsibilities like meeting with cabinet secretaries, writing public statements, choosing which issues to prioritize were carried out by Edith, all while she hid the truth of her husband's illness or the severity of it from the public. Beyond being First Lady, Edith Wilson was the first of many other things as author Rebecca Boggs Roberts details in her new biography, Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson.

Edith Wilson was the first First Lady to publish a memoir, the first to stand behind the President when he took the oath of office, and the first to travel abroad while her husband was in office, as well as accompany him to meetings with cabinet secretaries. She was even the first woman with a driver's license in Washington DC. Rebecca Boggs Roberts joins me now. Hi, Rebecca.

Rebecca: Hey, how are you?

Alison: I'm good. You opened the book. You take us to 1919. Woodrow Wilson has already had a stroke. Edith and his team are trying to make him presentable enough to visit some hostile congressman who want to know the truth. It is nearly like a Weekend at Bernie's scene.

Rebecca: It really is.

Alison: [chuckles] Why drop us there? Why start there?

Rebecca: Well, first of all, that scene is bananas. [laughter] It is this setup where members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee are tired of not hearing anything from the White House. They take an excuse of a complicated situation in Mexico to say, "We need to go find out the president's opinion on Mexico," and insist on showing up in person. The president was a really sick man, and his wife, Edith Wilson, his doctor, Cary Grayson, and his secretary, Joe Tumulty, had really conspired to keep that detail from everybody, the public, the press, the Congress, the cabinet, the president himself, the vice president, and had really just told everyone he was fine.

He was making decisions behind closed doors and they really needed to stop asking so much. This was the first moment when people really started to question that stonewall and say, "If he's okay, we need to see him, and if he's not okay, we need to know that." Edith and Cary Grayson and Joe Tumulty propped him up in bed and draped the blanket over his paralyzed left side and staged the whole thing with lighting that left him in shadow. It really is this Weekend at Bernie's moment and you think, "How did it get to this?" That's why I wanted to start the book there because you read that scene and you think, "Wait, what?" Ideally, it draws you in to understand the whole breadth and scope of the story.

Alison: What does it illustrate about Edith Wilson and how far she would go?

Rebecca: Edith Wilson was not afraid [laughs] to take control of almost any situation. She had confidence in her own ability to muscle on through. That's one of the reasons I wanted to write the book, is other biographies that concentrate solely on her time as First Lady. I get why. It's a fascinating chapter, but it's this sliver of what was a very long life. If you are only looking at that moment, you might be amazed that she did those things.

If you were paying any attention to Edith Wilson at all before that, you shouldn't be surprised she telegraphed again and again, that she was the woman who would take charge, who would manipulate a situation. It worked for her and her loved ones, and she really wasn't all that concerned with the truth.

Alison: You note in your epilogue that probably the only place where you can really find information or a tribute to Edith Wilson that does not include her husband is in her hometown. What did you learn from visiting where she grew up in Virginia?

Rebecca: She grew up in Wytheville, Virginia, which is in the southwest corner in the Appalachian foothills. Her childhood was not necessarily the one her family expected her to have. They had been planters in the James River Valley and after the civil war, they could no longer sustain a plantation without enslaved labor and had to move to these somewhat cramped little rooms over storefronts. She was the sixth of nine children. There were a lot of people in there, both grandmothers, a few aunts, a couple of cousins, various hangers-on.

She easily could have been lost in that shuffle, but she was singled out as a favorite by her totally terrifying grandmother who taught her somewhat unusually for the time that she was special, that she was smart, that she should rely on her own opinions, and she did have justifiable confidence. Meanwhile, she was getting from her other grandmother, and of course from society at large, the Victorian southern women should be pious and submissive and domestic message.

I don't want to psychoanalyze a woman too much 150 years later, but I really do think those two conflicts her natural inclination for strength and brains and confidence and the social expectations of submission and piety explain a lot of the contradictions of Edith Wilson. She was doing a lot and pretending she wasn't.

Alison: What was Edith's education like?

Rebecca: Limited, at least formally. That grandmother who singled her out, taught her to read and write, taught her the Bible, taught her French, which was a little bit of a mixed blessing because she had taught herself French that pronunciation was eccentric. Edith went to school for a year, hated it, came home, went to a different school for another year, loved that but that school, the headmaster got sick, and by the time it was time to figure out what happened next, she had three younger brothers who needed school more than a girl did and that was really it for her.

I think talking about her lack of formal education is a specious argument. I think that it's been used to cast her as this rube. This hillbilly figure who comes to the big city and is taken advantage of by politically savvy men. That's really not fair. She did come to Washington as a teenager, and she succeeded. She thrived. Washington was booming. It was the Gilded Age. She was not some hick. She became the woman she always thought she could be this sophisticated, stylish person of substance.

Alison: Why DC? Of all the cities she could go to, why DC?

Rebecca: Well she had a sister here. Her older sister was here and married and had a baby. Her first trip here was really to help out with that baby. She figured out pretty quickly this was the place that she could make the life she wanted. If you think about 1890s Washington, this is the world where people like Mark Twain and Edith Wharton had characters that reinvented themselves in Washington because the social strictures of New York where you are were much harder to navigate. It was a place where you could really figure out your role in society without running into Mrs. Astor's 400.

She took advantage of that fully and married a man who ran a high-end jewelry store here in town, Galt's. When he died and they were childless, she became a really unusual woman for the early part of the 20th century. She was independent. She had means, she was beholden to no one. She didn't need a chaperone. She had control over herself and her assets in a way that not very many women did. That's who she was when she caught the eye of the president.

Alison: I want to ask about Norman Galt. By all accounts, he was faithful and devoted and loving and good to her family. Was it a love match on Edith's end? It sounds like it was on Norman's end.

Rebecca: Norman was pretty smitten. Poor Norman, he seems like a perfectly nice guy. She dismisses him in a page and a half in her memoir.

Alison: Ouch. [chuckles]

Rebecca: I know, right? They were married for 12 years, and I don't know whether she downplays Norman in her memoir in order to foreground Woodrow, or whether it really was just a marriage of convenience to give her some status and security and get her out of Wytheville. A little bit of both probably. Norman was pretty in love. He was absolutely a stalwart, upstanding citizen. He was on every board. He volunteered for every cause. He was a good guy.

Alison: With Galt and with some of her other suitors and even Woodrow Wilson to a certain extent, there this sort of the feeling is not decidedly mutual. [laughter] It's just okay, there's an okay about this with Edith. What do you make of the fact that she seemed to be maybe dispassionate as too harder word, but maybe perhaps aloof when it came to romance?

Rebecca: I don't think that's an unfair word, aloof, I also need to constantly remind myself that she is the source for these things. Her memoir is often the only source for how she was thinking and feeling about things, and her memoir is at points demonstrably untrue. You have to wonder why she was presenting herself as aloof even if maybe she wasn't all the time. I think she liked that vision of herself as someone who was not particularly dramatic and hyper-feminine and was going to make the sensible choice all the time. It is true in her letters back and forth with Woodrow which are quite something. His are racy, steamy, and hers are very much not.

Every time he starts going on and on about her beautiful form and how he wants to kiss her eyelids, she changes the subject, and says, "Hey, what's going on in Mexico? What are you going to write to the Germans about the sinking of the Lusitania?" She was holding him at arm's length, even in the letters which are curated for just an audience of one.

Alison: My guest is Rebecca Boggs Roberts, the name of the book is Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson. Saw her memoir, titled My Memoir, [laughs] from 1938, as a source of information, and you write very beautifully that she tended to "embroider the truth." How did you work with that as a biographer, and as a journalist? How did you figure out what you could trust, and what was embroidery?

Rebecca: I mean, once you realize a couple of things can't be trusted, then you stop trusting the whole thing. Everyone in the Wilson administration wrote a memoir, I think there is no lack of documentation for those years. There were times when her version of events was directly countermanded by other people's versions of events, which meant I had to take a pretty cynical eye on the rest of it as well. No one was paying any attention to Edith Wilson before she married the president. Where I had no other sources, for instance, I'm taking her word for it, that her grandmother was terrifying.

The only thing I could do was build context around her, understand what Reconstruction Era Virginia was like. Understand what Gilded Age Washington was like, and place her in context in this very interesting life and times. I mean, she really did live through fascinating moments in US history. There weren't other people saying, "Actually, this is the way it went down," until she got to the White House, and then there were plenty of other people saying that.

Alison: My guest is Rebecca Boggs Roberts. We're talking about Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson will get into her time in the White House after a quick break.

[music]

Alison: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC I'm Alison Stewart. My guest this hour is Rebecca Boggs Robert. The new book is called Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson. Edith was introduced to Woodrow Wilson by her friend Cary Grayson, who would act as Wilson's doctor for pretty much his life. Grayson is often present in the anecdotes in this book. What do you make of this threesome, Edith, Woodrow, and Cary?

Rebecca: [laughs] Cary Grayson is an interesting character, and I hope somebody writes a biography just of him. He and Edith were friends before she met the president. They were mainly friends because Cary Grayson was courting a young woman who was a very close friend of Edith, Altrude Gordon, and Edith was the agony amps there. She gave them each advice, and she arranged times and places for them to meet, and she listened to all of their rollercoaster ups and downs of their relationship, which had quite a few. When Woodrow Wilson's first wife, Ellen, died in 1914, he was heart broken, and he was really lonely.

Cary Grayson was his doctor and was worried about him, was worried he was depressed and sad. Wilson and Ellen had three daughters who when they moved to the White House, were unmarried young women, and in the meantime, two of them got married and moved out. The third one wanted to be a singer. She was off on tour trying to have a career. He was rattling around that big old White House alone. He had a cousin Helen Bones, who was taking on whatever First Lady duties couldn't be ignored in a White House in mourning, and she was lonely, too, and worried about Woodrow.

Cary Grayson hit on this idea that Edith should befriend Helen. I think that was all staged from the very beginning. I think the ultimate plan was for Edith to meet Woodrow, but that's how Cary came in the back door. He asked Edith if she befriend Helen Bones, and Edith said no. She said she didn't want any part of official political Washington, that wasn't her wor, and Cary said, "You don't need to worry about official political Washington, the White House isn't doing anything. They're in mourning. She just needs a friend be nice." Edith and Helen became friends.

One of the things they did a lot was take walks through Rock Creek Park. Usually, they'd finish their walk and go back to Edith's house in Dupont Circle and have tea. One day, Helen insisted that they go to the White House for tea instead, which was a little weird. Edith said, "I've just been for a walk in the park. My boots are muddy, I don't want to show up at the White House and muddy boots." Helen insisted and swore they wouldn't run into anyone. They could go up the private elevator, don't worry about the boots. They go to the White House, and inevitably, because of course, this was a setup, they go up the elevator.

The elevator doors open, there is Cary Grayson and the President, and so they all have tea together. The President, more or less fell in love at first sight. He was just gone from the minute she stepped off that elevator, she took a little while longer.

Alison: He was pretty gobsmacked. He would sneak off to just watch her while World War I was going on. [laughs]

Rebecca: Isn't that amazing?

Alison: It is amazing.

Rebecca: I have to say, Alison, I never liked Woodrow Wilson very much. I've written books on the suffrage movement, you don't learn to say a lot of nice things about Woodrow Wilson in that context, but his letters made me like him more because he's so vulnerable and out there. He'll admit to sneaking into the green room and watching her through the lace curtains while she's at a lady's tea at the White House while he's President of the United States and trying to figure out whether or not the US should be involved in global conflict. He's catching a little sneak peek of his girlfriend.

Alison: You mentioned a couple of times that once they marry, she preferred to go by Mrs. Woodrow Wilson rather than the First Lady. What was her reasoning, why did Mrs. Woodrow Wilson mean more to her than the First Lady?

Rebecca: I think she hesitated to marry him in part because she had a lot to lose. That independence and social status was rare enough and enjoyable enough, frankly, that she knew giving up her independence and her privacy was going to be a very big deal. She also knew that she was going to be accused of being a social climber, not a gold digger because he had no money, and she had plenty but of wanting as she said, "The office, not the man." When she decided she would marry him, she was all in. She had taken a long time to think about it. She understood what was at stake, she understood what she was giving up, and she just jumped in with both feet, which was characteristic.

Also remember, she became First Lady overnight. She didn't have an on-ramp of any kind, and so she had to pick her public persona of what kind of presence she was going to have publicly. She picked dutiful wife. She never gave interviews, she showed up wherever he showed up to make his life easier, and she pitched that pretty well. I mean, if she was going for something that would be popular with the press of the day, she chose wisely, and so that Mrs. Woodrow Wilson's stuff was what she wanted to be known for. She wanted everyone to think that she was devoted to him, and it wasn't about national stature or fame in her own right.

Alison: It's interesting, because we said, "Oh, we'll book this book about Edith Wilson on Feminist Friday." She would not have liked that.

Rebecca: No, she sure wouldn't have.

Alison: Even though she behaved like one, she was not--

Rebecca: Right, but that's why I find her so fascinating. Actually, I think that there are more women stories like that than not at least 100 years ago, that women who made history had to pretend they weren't making history.

Alison: Was she truly anti-suffrage?

Rebecca: Oh, it kills me to say so but yes, she was. Why was this car-driving business-owning independent tradition-breaking woman anti-suffrage? Why didn't she want to exercise all of her rights as a citizen? I don't know. I think she never said exactly why. She certainly hated the tactics of the more militant National Women's Party, especially when they started picketing the White House in 1917 and really criticizing Woodrow Wilson very directly. She hated that. Even before that, she was anti. Some of it was just classist, I think. There was just a little something not nice about the suffrage activists.

If she wanted social cover, she could have had it. There were plenty of fancy society ladies in the movement. I think it goes back to that Victorian southern cult of true womanhood stuff that a lot of women at the time felt that there was something inappropriate about wanting to participate in public political life. That women's sphere was properly the private domestic sphere and that was important and that was something to be proud of. Wanting to participate in the men's public sphere, undermined the importance of that.

Alison: We know that Woodrow Wilson's name has been removed from high schools and buildings on Princeton's campus for the way that he resegregated the government and really destroyed a generation of Black wealth and progress and destroyed a lot of Black families. You noted from the book that she too was a bigot. Did she continue her bigotry in any formal way, considering that he really did consider her to be such a confidant and someone who he, as you point out, said, relied on more than any man in his administration?

Rebecca: The priorities of his administration had shifted so far away from domestic issues by the time they married because World War One was so overwhelmingly the issue that he had to deal with. Resegregating the civil service, showing Birth of a Nation at the White House, those things happened before they married. There wasn't much opportunity for her to weigh in on racial equality issues because that's just not what the administration was focusing on.

To its detriment, actually, I think that that's one of the really interesting parts about her legacy is, once World War I happened, and he negotiates the treaty in Paris, and she's there with him, and they come back here to Washington to fight with the Senate to make sure that the treaty is ratified, he focuses on that so much to the exclusion of all else. That when he got sick and when she really did take the reins of the executive branch, she kept all critical news from him. All he talked about, all he heard about was the Treaty and the League of Nations.

I'm not sure he knew what else was going on in the country. I'm not sure he knew about Mitchell Palmer's raids. I'm not sure he knew about the Red Scare. I'm not sure he knew about the labor unrest. His focus was really tunnel vision once the war came on.

Alison: To be clear, she was a woman of the South, her family enslaved people.

Rebecca: No question. Her memoir has some references to how happy her family's enslaved people were and how much they relied on the family and how at a loss they were after freedom. It's not. She was racist. I'm not afraid to say that.

Alison: We're talking about Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson. My guest is Rebecca Boggs Roberts. After Woodrow Wilson has the stroke, he was weak, he was bedridden. The idea was that even if he could do the work, if he was pushed too far, if that would have an adverse effect on his health, Edith adopted her role, which she described as a steward.

Rebecca: Yes, her stewardship.

Alison: What did her stewardship actually include?

Rebecca: How's that for a euphemism? According to Edith, the doctors came to her after his stroke, which was major. He was a very sick man, and said, if he is exposed to any kind of stress, if he gets out of bed, if he's not able to sleep as much as he needs to sleep, in other words, if he is President of the United States, he's going to die. If he quits, he's going to die because the only thing he's living for is to see this division of the League of Nations and global world peace and so he's got to stay in office. Also, PS if he dies, global peace will never be achieved. That's how high the stakes are.

If he does everything he's elected to do, he's dead. If he quits, he's dead. If he's dead, no world peace. From Edith's point of view, what could she possibly do as the most devoted wife? She could do his job for him until he was better enough to do it himself, which she claimed was not very long, and the stuff she did for him was not very extensive. That is hogwash. She controlled who saw him, she took meetings, she drafted public statements. Anyone in the cabinet who needed something wrote letters directly to her, she wrote back. She claims she consulted him in what she wrote back, sometimes, yes, sometimes no.

It went on for an extraordinarily long time. Now, I'm not sure she did anything he wouldn't have done. She knew his mind and his priorities quite well. She wasn't seizing control for her own agenda, but no one elected Edith to anything. It was 100% unconstitutional.

Alison: Is there anything in our daily lives today that Edith Wilson had an impact, that we can say, "Oh, this is because of that woman, in that period of time."

Rebecca: Hard to know because she covered her tracks so well. I think actually, the thing she did that had the most impact was keep him isolated because he lost such extraordinary touch with what the nation cared about, and even what the Democratic Party cared about. If you are only surrounded by people telling you, you are brilliant and healthy, and the nation loves you, you become almost delusional in your worldview. To the point where he thought he could run for reelection in 1920, which is preposterous. He never would have survived a campaign.

Even if he had, he wouldn't won. The nation had moved on. He dragged his feet for so long on saying whether or not he'd run again, that an [unintelligible 00:26:57] couldn't really emerge from the pack. Maybe Warren Harding would have won in 1920 anyway, maybe that's what the nation wanted, but the fact that the Democrats more or less forfeited that campaign because they couldn't nominate someone until the last minute, and they nominated James Cox. That might have been the biggest impact of that whole situation.

Alison: Edith Wilson lived for more than 30 years after Woodrow Wilson's death. That was longer than she'd even known him, when you really put it in that context. She really tended to the legacy of Woodrow Wilson. She really shaped the legacy, put up a firewall between what really happened and what she wanted the world to think happened. What else did she do with her life?

Rebecca: That legacy stuff was a real deal. You talked about how we're revisiting this notion of Wilson as a heroic figure. Well, where did that heroic figure come from? That was Edith Smith making. She really dedicated herself to that. She also went back to enjoying being an independent widow of means. She traveled the world. She was always very fashionably dressed. She had really good jewelry as you might imagine from someone who owned a jewelry store. Because she was here in Washington, when they left the White House in 1921 when Warren Harding was inaugurated, they decided to stay here in town, which no presidential couple had done at that point.

Now, the Obamas have done it. She realized as this First Lady here in town, that she had a role to play in welcoming future first ladies. She had each of them to tea regardless of party. Not to say, "Come pay homage to me, the grandam of first ladies," but to say, "I actually know this job is bonkers and really hard, and you've got a friend here in Washington." To me, that's a really interesting part of her post-Woodrow life that she saw a figure that maybe she wished she had had of someone telling her, "You're not wrong. Being First Lady is really crazy."

Alison: The name of the book is Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson is by Rebecca Boggs Roberts. Rebecca, thank you for the time today.

Rebecca: Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.