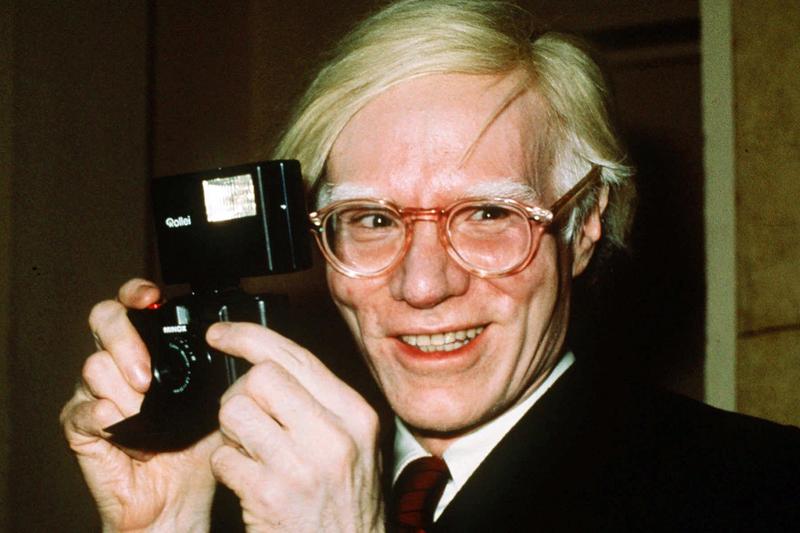

More Perfect's Season Finale Covers Andy Warhol and The Doctrine of Fair Use

( AP Photo/Richard Drew, File )

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC studios.

[music]

Brigid Bergin: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Brigid Bergen filling in for Alison Stewart. In May, the Supreme Court made a landmark decision over famed artists Andy Warhol's use of a 1981 studio portrait of musician and cultural icon Prince, taken by photographer Lynn Goldsmith. In a majority opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote, "Goldsmith's original works like those of other photographers are entitled to copyright protection even against famous artists." In the finale of season four, WNYC Studios podcast More Perfect revisits the case.

The episode investigates a previous court case involving rap group 2 Live Crew use of Roy Orbison song Pretty Woman. The nuances behind the legal doctrine of fair use, and they explore how the courts determine what is considered a transformative peace. The final episode of this season of More Perfect drops tomorrow, August 3rd. You can listen to this and previous ones at wnycstudios.org or wherever you get your podcasts. More Perfect Senior Producer Whitney Jones joins us to give us a preview of the episode. Whitney, welcome to All Of It.

Whitney Jones: Hi. Thanks to be here.

Brigid Bergin: Also joining us today is Alyssa Edes, who is a producer for More Perfect and featured in the episode. Alyssa, welcome to All Of It.

Alyssa Edes: Thanks so much for having us.

Brigid Bergin: Alyssa, let's start with the Prince portrait. In 1981, Lynn Goldsmith was commissioned to shoot a series of photos of Prince for Newsweek. He was just 23 years old when these photos were taken of him. What did those original studio portraits of Prince look like?

Alyssa Edes: Like you say, he's so young in his career. It's really interesting to see these photographs. They're black and white. The shot in question in the Supreme Court case is Prince from the waist up. He's wearing a white shirt, black suspenders. He's got this very direct stare into the camera. Lynn Goldsmith, the photographer had put on purple lip gloss and eyeshadow right before she took the shot.

Which is fun to imagine that conversation playing out with friends what lip gloss he wants to be wearing, but it's black and white so of course you can't see that. The thing that's so striking about the photo is he just looks really vulnerable. To me, it almost looks like the photographer's in control, and he's a little bit uncertain. He's just got this look of uncertainty, vulnerability, but very intent on the camera.

Brigid Bergin: I mentioned that he was 23, but just give us some context. Where are we in his career at this point? Are we pre or post Purple Rain?

Alyssa Edes: Pre Purple Rain. This is three years before his breakout global hit. He's released four studio albums by this time. Each one is successfully more successful. He releases one in '78, '79, '80, and '81. He is getting attention but he's still this up-incoming artist at the time, which is wild to imagine since Prince is the Prince that we know him in our culture today. It's just a year before his top hit 1999, and it's three years before Purple Rain.

Brigid Bergin: Whitney, in 1984 Lynn Goldsmith then licensed the use of one of her photographs of Prince to Vanity Fair for a special portrait by Andy Warhol for a feature that November. How did Warhol adapt Goldsmith's original work for this feature?

Whitney Jones: 1984 Purple Rain is now out and is at the top of the charts from August throughout the entire rest of the year. In that context, this is like three months into that. Warhol takes this photo that's black and white and he Warholizes it. It's like if you can imagine the Marilyn Monroe series. The background is washed in this red color, his face is now purple. There's some black around the eyes, his hair is black, his facial hair is black. There's some neon. It looks like hand-drawn lines around the face and some of the facial features, and you see it and it's like "Oh, that's a Warhol."

Brigid Bergin: Vanity Fair compensated Goldsmith for her original work, right?

Whitney Jones: Yes. Vanity Fair went to Lynn Goldsmith, I believe paid her $400.

Brigid Bergin: Oh, my goodness.

Whitney Jones: Got the licensing as a reference photo for this work. I don't think she knew that it was going to be Warhol. It was going to be the artist that was going to interpret it. Vanity Fair goes to Lynn Goldsmith and then goes to Warhol and be like, "Hey, we're doing this article about Prince. He is the biggest artist in the country right now. Do that for us."

Brigid Bergin: Wow. Let's fast forward to 2016, Alyssa. Prince has died. Vanity Fair's parent company Condé Nast puts together a tribute titled The Genius of Prince. It featured one of Warhol's portraits of Prince on its cover, and the company paid the Andy Warhol Foundation about $10,000 for use of that portrait. What happened to Lynn Goldsmith, while this is all going on?

Alyssa Edes: Lynn goes on to have a great career. She's a celebrity photographer, and so she's photographed so many different people that you would know. She took those photographs of Prince in 1981 and didn't really think about them again. I think she licensed them to some magazines over the years in the intervening time. Then just like everybody else you're seeing all this coverage of Prince's death, and she comes across this cover of the magazine with the Andy Warhol on it that is created from her photograph. She had never seen that. She had never seen that silkscreen, that portrait before. Go ahead.

Brigid Bergin: No, go ahead.

Alyssa Edes: To her knowledge, there was one portrait of Prince that Warhol created from her original photograph, but it turns out he actually created-- what is it, Whitney, 15 others?

Whitney Jones: Yes, 15 others.

Alyssa Edes: Yes, from that original portrait. One of them is what she sees on the magazine and she reaches out to the Warhol Foundation, and it's like, "Hey, what the heck. I didn't know about this. Let's talk."

Brigid Bergin: Now we're getting into the fair-use space, Whitney. The Warhol Foundation argued that Warhol's portrait was transformative in legal terms because his artistic rendering was different enough from Goldsmith's original work. What legal ground did they have to stand on here? How could Warhol's rendering potentially have fallen under this fair use? I'm doing air quotes category.

Whitney Jones: I want to carry out this with like I am a podcast producer, I am not a lawyer. My legal understanding is based on having done stories about copyright over and over and talking with other people. Copyright has always been a limited right. There are times when you can break somebody's copyright, and a judge can determine if that's okay to do.

Judges over the years have basically created this thing that we call fair use where they've outlined under certain circumstances or certain ways in which you can take a pre-existing work and change it and do something different with it and that could be okay.

There's no checklist. It's not like as an artist you can be like, "Oh, I've done one, two, three so this is fair use." You have to violate copyright, you have to then get sued, and then a judge determines, "Well, this falls on this side of line, this falls on this side of line."

Brigid Bergin: Well, speaking of judges, I want to play a couple of clips from the podcast to hear how the Supreme Court justices tried to unpack this particular case. Because it's sort of surprising, I will say. This first clip is about a minute and a half. This is a discussion between the Supreme Court justices over whether the work is actually transformative.

Alyssa Edes: If you didn't know, this is what the justices do.

Male Speaker 1: Let's say somebody uses a different color.

Alyssa Edes: It might sound like they're just going off the rails. Here's Clarence Thomas.

Clarence Thomas: Let's say that I'm both a Prince fan, which I was in the '80s.

Amy Coney Barrett: No longer. [laughter]

Clarence Thomas: Normally on Thursday night. Let's say that I'm also a Syracuse fan.

Alyssa Edes: He's like, "What if I make a giant orange Prince head poster for a Syracuse game."

Clarence Thomas: I'm waving it during the game with a big Prince face on it, go orange.

Alyssa Edes: Go orange. Is that transformative?

Amy Coney Barrett: If a work is derivative.

Alyssa Edes: Then Amy Coney Barrett brings up Lord of the Rings.

Amy Coney Barrett: Like Lord of the Rings book to movie.

Male Speaker 1: I don't think that Lord of the Rings has a fundamentally different meaning or message but I would have to probably--

Amy Coney Barrett: Really?

Alyssa Edes: Seems like she's a fan.

Male Speaker 1: I would probably have to learn more and read the books and see the movies to give you an affirmative decision on that. I recognize reasonable people can probably disagree on that.

Alyssa Edes: It goes on like that for a while, until--

Male Speaker 2: Thank you, counsel.

Male Speaker 1: Thank you.

Alyssa Edes: That's all pretty weird and interesting, but then justices making pop culture references.

Then Justice Roberts chimes in like this. John Roberts is like, "Isn't Warhol doing something bigger?"

Justice Roberts: It's not just that Warhol has a different style. It's that unlike Goldsmith's photograph, Warhol's sends a message about the depersonalization of modern culture and celebrity status and the iconic. It's not just a different style, it's a different purpose. One is to commentary on modern society. The other is to show what Prince looks like.

Amy Coney Barrett: Yes, I think-- right.

Alyssa Edes: Goldsmith's lawyer is like, "You're missing the point."

Amy Coney Barrett: What I think all this goes wrong is you're just focusing on meaning and message independent of the underlying use.

Alyssa Edes: In other words, this isn't about aesthetics, this is about money and the market.

Brigid Bergin: Wow. Whitney, Alyssa, can we talk about how the Supreme Court justices ultimately decide this?

Whitney Jones: Yes. There's this previous decision that in some way takes into account the aesthetic changes being made to an original work. I think in this current decision the court sets aside those. They're very concerned with not being seen as art critics because those are not clear legal lines in areas they like to work. It's like they're very conservative not being seen as art critics. In this case, they put aside a previous standard that had included some of those aesthetic evaluations like have you changed the meaning and message of a work? What does that even mean first of all?

In this decision they move away from like, was Warhol okay to do this in the first place, and look at the foundation's licensing of the work to the magazine as the thing that they're actually going to comment on. They say that in licensing this image to the magazine, they're doing the same thing as the original photo. Lynn was licensing her photo out to magazines to illustrate articles about Prince as well, and because those have the same purpose, no, there hasn't been transformation here. The foundation is not okay to use the Warhol work in this way.

Brigid Bergin: Alyssa, when was the last time the Supreme Court dealt with a case this?

Alyssa Edes: The last time something this came up was all the way back in 1994 with the case revolving around 2 Live Crew. They do this parody or they do a cover their own version of Roy Orbison's Pretty Woman. That is the case that lays the foundation for what the arguments in this current Warhol case were revolving around.

Brigid Bergin: We have a little clip from that part of the podcast as well. Let's take a listen to that piece. Just before I throw to it we'll set it up a little bit more that this is related to 2 Live Crew's use of Roy Orbison's Oh, Pretty Woman and just a little bit of more from More Perfect.

Alyssa Edes: In this spirit of humor, they're taking things they think will be recognizable and making fun of them. In 1989, they land on the Rory Orbison song-

[MUSIC - Rory Orbison: Oh, Pretty Woman]

-as something that would be fun to rip and mix.

[MUSIC - 2 Live Crew: Oh, Pretty Woman]

2 Live Crew: Childish humor, that's what we were doing. It was childish humor in a way where it could be a lot of money was made, but their beef was is that we didn't get permission from them to do it.

Alyssa Edes: To no one's surprise they get sued, and they end up in the Supreme Court.

Brigid Bergin: Alyssa, what conclusion does the court to come to in the end?

Alyssa Edes: In that case, with 2 Live Crew it's a unanimous decision, and the justices say that this is a parody that is a clear example of fair use. They introduced this new standard in order to decide what's fair and what's not to use. Like Whitney was talking about, this has always been kind of a murky area of the law. In this case, they sort of codify in a way this standard called the transformative use standard, which came from a lower circuit judge who I spoke with. That's how we get the question, is it transformative in the Warhol case between the Goldsmith photograph and the Warhol silkscreen?

Brigid Bergin: It's so fascinating how these cases build on each other and how these standards build on each other. Can you talk about-- I think as you said, it is the transformative standard that links to the Warhol, but this is really central to the Warhol case. Do you want to pick that up, Whitney?

Whitney Jones: Yes. To answer your earlier question, when Warhol Foundation's lawyers are arguing their side, this is what they're arguing. They're saying, "The same standard that you applied in the previous case about 2 Live Crew should be applied here." Warhol very clearly, artistically, aesthetically has changed the meaning and message of the photo. Applied in the same way as the Campbell case, the 2 Live Crew case we should win. Warhol has transformed the thing and we should win according to that standard.

Brigid Bergin: Alyssa, this was a long battle for Lynn Goldsmith. It took six-and-a-half years. How did the Supreme Court end up taking on this case in the first place and why?

Alyssa Edes: Such an interesting question because I think a lot of people have this idea that cases just dribble up to the Supreme Court somehow. They just trickle up and then they arrive. The justices actually have a lot of control over which cases they take and which they don't. There has to be four justices on the bench who agree to take a case. This usually involves because there was a conflict in the lower circuit courts.

I actually was told on background by a source who is pretty close to the Supreme Court that she thinks that they took this case for fun. They got a lot of heavy stuff on their docket. Why not get some pop culture Warhol, Prince action in while we can, and who knows? Who knows if that's true? We don't really ever know why the court decides to take one particular case or not.

Brigid Bergin: Whitney, the case has received a lot of press coverage. Obviously, we're dealing with these pop culture icons, but what are some of the other things that have made this case so fascinating? Why were you interested in it?

Whitney Jones: Because I'm a nerd about copyright and fair use issues. This is the third piece I've done.

Brigid Bergin: Sweet spot.

Whitney Jones: Yes. No, I love this stuff. From the work that I do in podcasting, I've used a lot of things from other places over the course of the things I've made and it's a thing that I find enjoyable to do. I come at it from a personal interest. I think coverage generally, you look at the Supreme Court's docket this term, and then you see this case that involves Prince and Andy Warhol, and I don't think it's much more complicated. I was like these are massively important iconic American figures. I think if there's a story to do about them, I'm going to do it. I think a lot of ones probably feel that way too.

Brigid Bergin: As you mentioned, you are not a lawyer, and Alyssa, I don't know, but I think that you are not-

Alyssa Edes: Also not a lawyer.

Brigid Bergin: Also not a lawyer. Three not lawyers digging into the Supreme Court. Let's pull back the curtain a little bit on your process for More Perfect. I know there's a great team of people who are involved in making the podcast. Can you talk about how you start to take some of this really dense legal language and make sense of it? Who are some of your advisors that really help guide you through the reporting process?

Alyssa Edes: Oh, that's such a good question. In our show, we have a lot of background conversations before we start digging into tape and crafting a story to make sure that we understand what we're talking about. We talked to several people who are lawyers on background. One of our legal advisors is Sam Moyn at Yale. He's a professor, and he was immensely helpful in trying to figure out not only what is going on in this case, but really what it can say more broadly about art and American culture and the law.

Jeannie Suk Gersen is another legal advisor who we work with. She's a writer at The New Yorker, and she's a professor at Harvard. She also helped explain what's going on in the opinions, and what does this case tell us about how the court works? So yes.

Whitney Jones: I'm sorry. I was going to say, another thing that made this one fun, I think among the team is that, again, none of us are lawyers necessarily. This case there's something about it and the fact that it's about art and you can argue about it. There are very different opinions about this case inside of our team, and it made it a really fun piece to work on and work through and argue ideas about and make it all into one piece at the end that hangs together.

Brigid Bergin: As we said, the court ultimately ruled against The Andy Warhol Foundation. Just briefly, Whitney, what implications do you think this decision will have for artists?

Whitney Jones: It's really difficult to say until more cases come up with this as their background. I think it's clear if you were a photographer or somebody making original art, if somebody then takes that and makes something from it, it's maybe easier to bring a case now. I don't know that we know much beyond that.

Brigid Bergin: Well, we will have to leave it there for now. My guests have been Whitney Jones, senior producer, and Alyssa Edes producer on More Perfect Season 4. It's a nine-episode series. You can check out the latest episode and the others coming wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you so, so much for joining me on All Of It.

Alyssa Edes: Thanks for having us.

Whitney Jones: Thanks for having us.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.