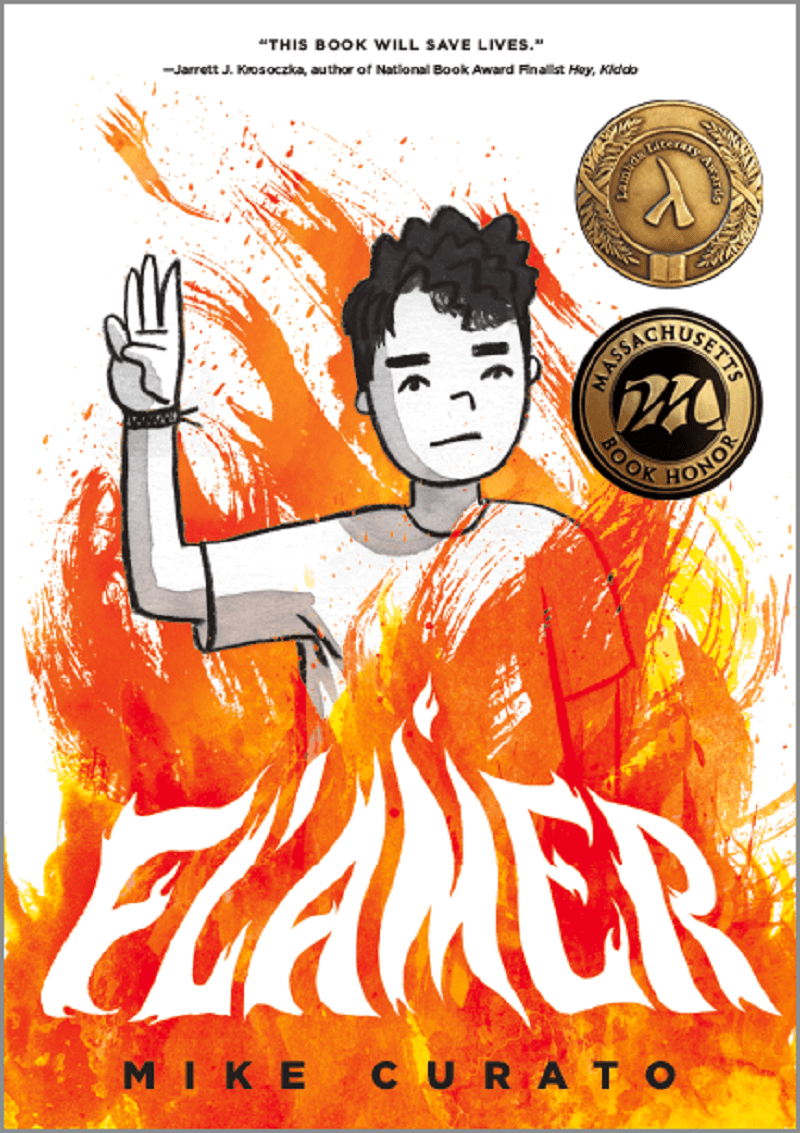

Mike Curato's Graphic Novel 'Flamer' (Banned Books Series)

( Courtesy of the Author )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All of It from WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. As part of our Pride coverage all month, we've been giving a signal boost to authors whose work has been banned or challenged with particular attention to those books with queer themes and or protagonists. We've arrived at the fourth most challenged book of 2022, according to the American Library Association, titled Flamer. It's about a kid trying to figure out who he is. Aiden is 14. He just graduated from middle school.

He's not really good at sports, and his doctor said he should lose a little weight, and he often feels a bit different from the other boys his age. During summer break, Aiden attends boy scout camp, and a lot of times things are okay. He's outdoorsy, he can canoe, he makes a few friends. Always lurking are bullies, including his own inner critic who taunts him as he comes to term with his identity. At one point, Aiden says to himself, "I know I'm not gay. Gay boys like other boys. I hate boys. They're mean and scary.

We learned at school how bad homosexuality is. It's a sin. Gay people do bad things, and I'm not a bad person. I try to do good all the time, so I couldn't be gay." Flamer is a graphic novel based on the life of illustrator and novelist Mike Curato. Since Flamer's publication in 2020, Curato received the Lambda Literary Award for Children's and Young Adult Literature in 2021. Caucasus review calls it "A story that will be read and reread, and for some, it will be the defining book of their adolescence.

His book also caught the attention of detractors like parents and school board officials in Oklahoma, Michigan, and Florida. By the end of 2022, Flamer became one of the most challenged books in America for its "inappropriate and sexually explicit themes." With me now to talk about Flamer is graphic novelist Mike Curato. Mike, so nice to meet you.

Mike Curato: Hi, Allison. It's so great to be here.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, this conversation may touch on suicidal ideations. Want to make sure we give you this number in case you need help. 988 is the number to call for the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. It is open 24 hours a day. Your background is in children's books, for little kids with these whimsical titles like The Sherry Godmother. Many of them feature animals and fictional creatures. What inspired you to write a young adult graphic novel with some very very real themes?

Mike Curato: Yes. One of my fellow challenged band authors, Tony Morrison, once said that if there's something you want to read and it doesn't exist, then you have to write it. That rang true for me. Before I was a published author, I had an idea about a book that I didn't have when I was young. Then in 2014, there's been We Need Diverse Books campaign that was taking off, encouraging more representation in children's literature. Queer youth are so underserved and children of color are underserved. I finished writing the book and here we are.

Alison Stewart: How would you describe Aiden?

Mike Curato: Aiden is a more courageous version of my younger self. He is very sweet and giving and kind. He is a chubby Filipino, white mixed kid, and he's just trying to make his way and make sense of everything.

Alison Stewart: Did you ever consider writing this with a character named Mike, just making it truly autobiography?

Mike Curato: I did consider it. I tried a few different routes when I first started writing it, and ultimately I decided that fiction was the way to go. It just gave me more leeway to encapsulate a lot of my life experiences into this one week of summer camp.

Alison Stewart: I was going to ask you about the device. It is one week of summer camp. What is it about a week of summer camp that is so intense?

Mike Curato: Okay, great question. I have been a camper, I've been a counselor. Basically, so much can happen in just one day of camp. First of all, it's an opportunity for a young person to experience this liberated environment. When we're young, we're used to going to school and then we go home. Summer camp, I don't know, there's a little more freedom. You feel a little more independent. Along with that, there's all this drama. When you're at school, you're around people for a few hours a day, and then you go home.

Now you're around your peers, literally 24/7, and a lot of emotions can run high. You could be at the top of your game in the morning. By lunch, you could be a social pariah. By dinner, you're besties with everyone again.

Alison Stewart: This actually made us think we wanted to do a listener call as we discuss your book about summer camp, because Flamer takes place at a summer camp, a week in summer camp, and it's such a formative experience in people's lives. We want to know if you experience something similar to Aiden. What was it that happened to you at camp? Was it a friendship, something that happened one summer that really changed how you think about something or think about yourself? Our phone lines are open, 212-433-9692, 212-433 WNYC. You can also text to us at that number.

Everybody, go back in your memory banks, think about something extraordinary that happened to you at summer camp or a way that it shaped who you turned out to be. 212-433-9692, 212-433 WNYC. In the book, Aiden is wrestling with his identity. There's a lot of name-calling, words that we can't use. People can guess what they are. He never really comes out in a big splashy way. Why did you make that decision?

Mike Curato: That wasn't my experience. I think a lot of people don't have that experience of, I'm going to come out to everyone all at once. I pulled the band-aid off rather slowly [laughs] and when I was much older. Aiden is just learning to accept that part of his identity. He still has a long conversation to have with himself. I think we should all be given that room and that grace as we're growing up to figure it out on our own and not have to make some big declarative statement.

Alison Stewart: I want to describe for people what the book looks like. It's in black and white and shades of gray. Then there are just these bursts of fiery orange-red flame like that pop out. They are in interesting places. At one point, it's around a heart. At one point, it's a little bit of blood dripping from a finger cut. At one point, it's just all the terrible things that Aiden is thinking. He's a little tiny black and white figure in the corner. All the words are just like in this red dark, fills the entire two pages. What went into the decisions of when to use color and specifically this color?

Mike Curato: First, you saw what I did there. The orange, red color, the title is Flamer. There's definitely a theme of fire. The color is reserved for these emotional touchstones throughout the story. They're highlighting emotions or objects or people that I want the viewer to pay specific attention to in this moment. Reds and oranges, they could be a color of anger. It could be a color of love. It could be a color of passion, whether that's religious passion or whatever. There's a lot of power behind that color.

If you allow me to segue, I chose the title Flamer because it was used as a derogatory term when I was growing up, but when you think about the power behind the concept of fire, it was something that I wanted to reclaim. That's all connected.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Mike Curato. The name of the book is Flamer. He's the illustrator and the writer of this graphic novel. It was one of the most challenged books of 2022. A lot of the challenges talked about some of the queer themes, but you really get into some of the other ways that Aiden feels othered, whether it's his race or his weight or his mannerisms, or about what he likes. One bully taunts him about his eyes. Why was it important to write about his experiences beyond his sexual identity?

Mike Curato: We as people have multiple layers to who we are. That's one thing that a lot of queer people experience in the world is that we are stigmatized, we're sexualized. Everything about us is somehow about sex, and that's not the case. We're three-dimensional human beings, just like any straight person we're not defined by our sexual identity. We're not a monolith. I wanted to show all the ways that Aiden is different and all the ways that he's picked apart by other people. That's a lot of stress for anyone to go through, when all these different aspects of who you are, are challenged and questioned.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Elise, who is calling in on Line 1. Hi, Elise. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Elise: Hi. How are you? I'm enjoying the program very much.

Alison Stewart: Great. What was your camp experience?

Elise: My camp experience, I started going to camp when I was very young, and I enjoyed it. It was really a highlight for me. Coming to New York City as an adult, I've made the Fresh Air Fund, one of the leading charities that I donate to because camps are great for all the reasons you're talking about, and I think every kid should have that opportunity. Great show. I look forward to reading the book. I can't wait.

Alison Stewart: Elise, thank you so much for calling in. Faith and religion are a part of this story. It's a thread in the book, something very-- I won't give too much away, dramatic happens with Aiden and his faith. When you think about the role of faith in Aiden's life, what's been a positive in Aiden's life, and what's been a negative?

Mike Curato: I think positive is that he draws a lot of hope from his faith and he is trying to use it as a roadmap to be a good person and I think majority of us, that's all we really want to be good but within that, the challenging thing for him is like, okay, I'm trying to be good, but my religion is telling me that this part of me is something bad and but it's something that I can't help, so what do I do? Am I stuck in that? That is a big question that I had to grapple with for many years.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, we want to get you in on this conversation. Flamer takes place in a week in summer camp, and it turns out to be a formative experience in Aiden's life, the protagonist. We want to know if you experienced something similar, maybe it was a camp friendship, maybe you really came into your own at camp that changed how you thought about yourself or the world. Give us a call 212-433-9692. 212-433-WNYC, that's our phone number, or you can text us. We heard from Elise earlier.

One of the things I really liked about the book, Mike was that not everyone is a mustache-twirling bad guy. [laughter] There there are some really bad kids, and you have a mustache, by the way. There's a lot of kids who just want to be Aiden's friend, some kids who aren't sure but have to figure out if they want to or not and that's reasonable as well. When you were thinking about that balance of how the kids would react, what were some of the versions, things that you threw away, maybe things you kept, things you knew you wanted to do, things you knew you didn't want to do?

Mike Curato: I think it is lazy to cast a bully, particularly in a two-dimensional light of just, that's the bad guy, especially when we're young. We were just trying to make our own way. People may make some decisions, some poor decisions, some fear-based decisions that affect other people negatively, and some people make poor decisions, and they think that they're helping, so I wanted to show that spectrum. There is a bully at camp that tortures Aiden a lot, says all these mean things, but we do see this moment where he's a little vulnerable.

Aiden claps back and then this guy is feeling sad and you're like, oh, someone else has feelings. Then we see one of Aiden's friends, someone that we think is his friend, and he thinks he's doing him a solid by suggesting, hey people are going to say stuff, so maybe you should act differently. That's definitely, I think something more common, where people, they're coming from a place of love or concern, but not really supporting the person. I wanted to show, hey, we can all be heroes and villains if we wanted to be.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Mike Curato, he's the author of the graphic novel Flamer. As I mentioned, it is I believe, the fourth most challenged book of 2022 by the American Library Association's count. When did You first realize that people were starting to say not great things about your book?

Mike Curato: Well, it was a while, Alison. It came out in 2020 and it was a year and a half of frosting and a lot of cherries on top, just people being really kind and sharing the book. Then in '21, a Texas lawmaker came up with this McCarthy-esque List of 800 some odd books that he wanted investigated. It's a political ploy, it's an old move and that's when all this hate started coming in. Flamer in particular, and other graphic novels like Gender Queer, by Maia Kobabe, they've really been exploited, because it's easy with the graphic novels, since it's so visual to take a quick photo, you cherry-pick a few lines, and suddenly people are saying it's pornography.

It's been a snowball, since that list, I would say.

Alison Stewart: If you could sit down in a room with one of these people who is saying, "I don't think this should be in my child's library," or, "I don't think children should have access to this." If you could really have a one-to-one conversation with someone, how would you start that conversation? Not that you should have to, but to be clear, but just hypothetically.

Mike Curato: I think there's a few things that need clarification. First of all, my book is a book about teenage life, for teenagers. I think some people are getting things misconstrued that this is somehow in elementary schools or something. It deals with some hard topics, but there are topics that we can't just ignore when they're a part of teenage life. Second of all, this isn't a book about sex, which is, of course, when we talked about before, since it's a queer theme book, people make this assumption that it's all about sex, and there is no sex in this book.

There's nothing explicit in it. Again, they are implied things, things that teenagers talk about but the big message that I want to tell people is that by removing a book from a school, from a public library, you're sending a message to the people that book represents, you're telling them, we don't want you to be here and this is what's causing real harm to children, not my book, not these other books being banned. The real harm that's being done is the messaging. You're creating a hostile environment that's unwelcoming and it's it's a dog whistle to people with prejudices who feel now emboldened to be like, yes, I am going to call that kid, the F word.

I am going to exclude this genderqueer person from my friend group, because, I guess the powers that be are saying that they are weird, so we should stay away from weird. That's my message. If you are doing this in the name of protecting the children, I would say take a big step back and reconsider that.

Alison Stewart: Let's slide one more call in. Serena, you have about 45 seconds. You're on the air.

Serena: Hi. I just want to say I love the program. I'm a genderqueer lesbian who went to camp for many summers and the total unsupervised chaos of being at camp without your parents or without your home structure really helped me figure out how to dress, how I want to dress and present myself how I want to present and it was really changing. It was so freeing in a way that you can't really get at home. That's my camp experience. I can't wait to read the graphic novel, graphic novels helped me realize my sexuality too. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: Serena. Awesome. Thank you so much for calling in. Once again, the name of the graphic novel is Flamer. It is really quite beautiful. I've been speaking with its writer Mike Curato. Mike, thank you so much for being with us and taking some listener calls.

Mike Curato: Thanks so much, Alison.

Alison Stewart: That's All Of It for today. I'm Alison Stewart. I appreciate you listening and I appreciate you. I will meet you back here next time.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.