A Memoir of Kidnapping from Poet Shane McCrae

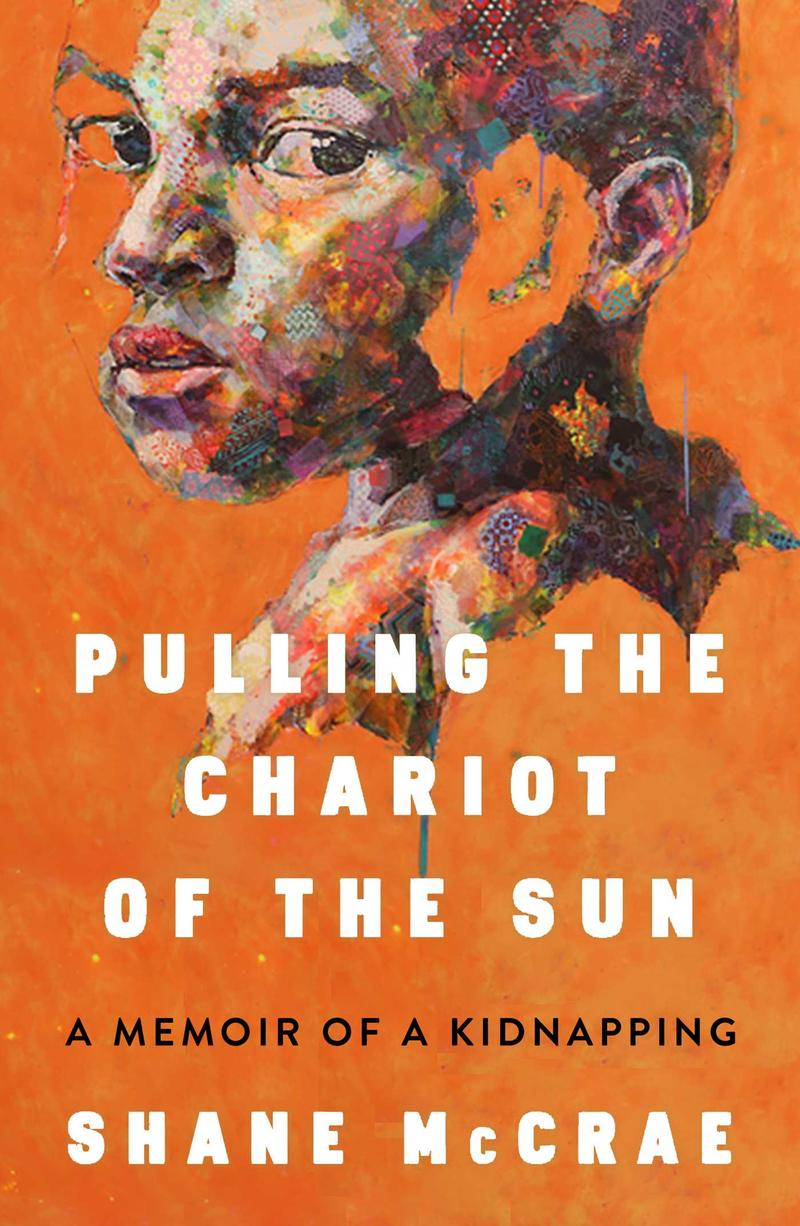

( Courtesy of Simon and Schuster )

Voice-Over: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

[music]

Bridget Bergen: This is All Of It on WNYC, I'm Brigid Bergen, filling in for Alison Stewart. When Shane McCrae was about three years old, he was forcibly separated from his Black father by his white maternal grandparents, who were also white supremacists. While he remained in contact with his mother from time to time, he wouldn't see his father again for 13 years, a man he barely recognized. He writes about his childhood and upbringing in his new memoir, it's titled, Pulling the Chariot of the Sun: A Memoir of a Kidnapping.

In the book, he shares the story of how he came to start a new life in Texas with his grandparents, his grandfather's abuse, moving to the West Coast, and struggling to make friends as he sifts through his memory to reconcile the stories his grandparents told of his origins, how he remembers his life, and what actually happened. In New York Times profile from The Sunday Magazine, it states that the book is "the story of an undoing, but is no less a story of becoming." The memoir is titled, Pulling the Chariot of the Sun: A Memoir of a Kidnapping.

It Comes out tomorrow, August 1st. Tonight, author Shane McCrae will be in conversation with poet Patricia Smith at Books Are Magic in Brooklyn Heights at 7:00 PM, but first he joins us now. McCrae teaches at Columbia University, is the author of several poetry collections, including The Gilded Auction Block in 2019, In The Language of My Captor in 2017, and The Animal Too Big to Kill in 2015. Shane, welcome to All Of It.

Shane McCrae: Hi, Brigid. Thank you for having me.

Bridget Bergen: I want to start with the kidnapping. What happened on the day you were separated from your father?

Shane McCrae: I actually just discovered from reading that profile that I was-- I guess I would have been three years old and nine months, but I don't really remember it. My understanding is that I was with my father in Salem, Oregon, and my paternal grandfather had died very recently, maybe that day. My father wanted to take me to the funeral, which would have been in Arizona. My maternal grandmother came by and said, "Before you take him, can we have him for the night," my maternal grandparents, and my father said, "Sure."

What happened then? My grandmother took me, but didn't-- my father had been under the impression that my grandparents were still living in Salem. Unbeknownst to him, they had moved to Portland. My grandmother took me with her, didn't tell my father where she was actually taking me, instructed my mother not to tell my father where I was. Then I guess maybe a few days later, my grandparents moved with me to Texas and didn't tell my father.

Bridget Bergen: What stories did your grandparents tell you about your father?

Shane McCrae: They told me that he didn't want me, that he was busy with a new life and other children. They also told me that he had decided he was no longer interested in me when I was 18 months old, and that I had been living with them ever since, which was actually two years before it actually happened. The main idea was that he wasn't interested in me and never had been.

Bridget Bergen: Throughout this, how often did you see your mother? What role did your mother play throughout your childhood?

Shane McCrae: I honestly do not know. My memory of it was it wasn't that often. We always lived in the same city-- not always in the same city, often in the same city. Sometimes she would live in another nearby city, but it being Texas, nearby is relative. Maybe every few weeks, maybe every few months. I really don't know. My excitement when she would come to visit, my memory of that excitement suggests to me that it couldn't have been more than every month or so or maybe every few months.

Bridget Bergen: The book is both so beautiful and so painful to read. One theme that runs through it is your grandparents' racism. What kind of space did they make for you in their lives? How did they perceive your Blackness in their home?

Shane McCrae: Honestly, I don't know how they perceived it. Particularly, my grandfather didn't like Black people, and he was vocal about that whenever he got the opportunity. I think that he probably toned it down because I was in the house, but they also never really emphasized that I was Black. When I asked why I wasn't the same color as them, they said it was because I tanned easily, and yet I still have some memory of being aware of being Black. There was a double consciousness going on.

I think that they made space for me just by not really thinking about it, which I think is, to some extent, easy to do when you're raising a child, you have other things to think about. I don't really know how it worked for them.

Bridget Bergen: For you then, when did you start to feel something was off, that something wasn't right? How long before you could use the word "kidnapping" to describe what happened to you?

Shane McCrae: Well, I think I always felt that something wasn't right. I don't have a memory of feeling perfectly comfortable and normal, although who's to say. I guess I don't know what normal feels like, so feeling not normal was normal. [laughs] I guess I can't say for sure, but I don't think I ever felt right in that home. When I started to feel comfortable thinking of it as a kidnapping, probably it could have been in my 20s, it could have been in my 30s.

Bridget Bergen: Wow.

Shane McCrae: It wasn't until really two or three years ago that it really sank in. I'm not sure why it took that long. I think it was hearing my father tell the story of me being kidnapped, which I think that he tried to avoid telling when my grandmother was still alive. Hearing him tell the story suddenly unlocked, I guess, an awareness of what it meant having been kidnapped. In some ways, it feels very fresh even though it was rather a long time ago that I became aware of it.

Bridget Bergen: You talk a lot about how physically and emotionally abusive your grandfather was. Where do you think that anger came from?

Shane McCrae: Well, I really don't know. He grew up, as I understand it, pretty poor, in what seemed like really not great circumstances. I don't know anything about his parents really at all. I can't really account for his anger, his particular violent anger. For whatever reason, my grandparents weren't especially forthcoming about their families, my grandmother more than my grandfather. I knew really almost nothing about his family, his upbringing.

Bridget Bergen: Can you describe the relationship between your grandmother and grandfather?

Shane McCrae: Not really. [laughs]

Bridget Bergen: [inaudible 00:08:52].

Shane McCrae: Yes. I don't think I ever saw them fight, which is not to say that they had a good relationship. I guess the closest I came to seeing them fight was when my grandmother told me that they were getting divorced because my grandfather had been sleeping with sex workers. I don't think I got to see much of their relationship. He drank a lot, constantly drinking. Really, I just remember we all sitting in the living room and being quiet. I don't remember any conversations they had other than them talking about the divorce.

It wasn't demonstrative. I don't remember them ever kissing. I'm sure maybe they must have at some point, but if they did, I have no recollection of it. Yes, very quiet is what I can say about it.

Bridget Bergen: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Brigid Bergin, filling in for Alison Stewart, and I'm speaking with Shane McCrae, an author and poet, about his new memoir, Pulling the Chariot of the Sun: A Memoir of a Kidnapping. It is out tomorrow. He has an event tonight at Books Are Magic in Brooklyn Heights. It's at 7:00 PM with Patricia Smith. We're talking about writing a memoir. As I said, you have these collections of poetry you've done, but you decided to put this story in another form. Why did you want to write a memoir about these experiences?

Shane McCrae: I've written poems about it. I think writing poetry was how I started writing. I think writing poems makes me the happiest. I did write the memoir in a way that was very similar to the way that I write poems, the way I approached it. I think that I had some awareness that I couldn't really get the whole story into poems. You can, but it works differently. I thought that I wanted to have some kind of record while I still remembered what little I do still remember. I'm always, as a writer, trying to do something new and always anxious that I'm not doing enough that's new.

Writing a memoir, particularly because I'm very worried that I can't write prose at all, felt like a very big new scary thing, and that made it attractive.

Brigid Bergin: These are your words, so no fear. I'm wondering if I can ask you to read an excerpt from the memoir perhaps starting on page 140.

Shane McCrae: Yes, I would be happy to.

Brigid Bergin: Thank you so much.

Shane McCrae: Okay. A teenager is a person who has begun to realize they're a person. I became a teenager early during my first months in California when I was 11. While my peers at East Avenue were starting to think about the lives they might someday have, I could think only about the life I already had and from which I was sure I would never recover. Never as a teenager could I imagine a future for myself. By the time I was 15, I was certain I would die when I was 18 because what's beyond 18?

When I was a child, I wanted to grow up to become a baseball player. When I was a slightly older child, after I got hit in the eye with a baseball, I thought I might grow up to work at IBM because my grandfather worked there. When I was a teenager, I couldn't imagine growing up. I didn't aspire to be more than the harm done to me. I didn't want to outgrow it. My grandfather had started beating me almost immediately after my grandparents kidnapped me. The chain of beatings bound me to the kidnapping, that great wound at the beginning of my life.

Before the beginning of my life, before the kidnapping, I was waiting still unharmed. Not a separate self but my actual self, my whole self from which fragments proliferated forward through time as me. To imagine my future life would have been to lose sight of the chain binding me to that distant self.

Brigid Bergin: That's Shane McCrae, author and poet, reading from his memoir, Pulling the Chariot of the Sun: A Memoir of a Kidnapping. Shane, there are often details shared in this memoir that you revisit. For example, the book opens recalling that trip to a fabric store with your grandmother, but you're not sure what age or what day. Why did you begin the narrative of your life in this particular trip to the fabric store and these choices you made about the moments that you share?

Shane McCrae: I knew that my memoir would have to be a memoir about memory to some extent because I think in order to survive my childhood, I actively blocked out a lot of things that happened to me. I think I did this starting pretty young. A consequence of this has been I think my memory has been consuming itself for decades and so there are a lot of holes, a lot of things I forget. I wanted to start with that particular image of going to the fabric store, the sideways rain that I saw that day because it was a really vivid thing.

I could still see it in my mind, the rain sweeping across the parking lot and feeling I had never seen such a thing before. It might seem like maybe a bit of an idiosyncratic place to begin, but for me, because the book is about remembering as much as it is about my life, I wanted to start with a memory that was very strong for me. The reason the book is sort of recursive and returns to things and repeats things is it's trying to make the memories more palpable. It's trying to sort of give them an almost physical presence in the landscape of the book.

Brigid Bergin: We just heard you read this passage about life as a teenager. As you look back on young Shane, what did he think about his life back then and what did he think of himself?

Shane McCrae: As I said in the part that I read, I really couldn't imagine getting any older than 18. I, starting very young, had sort of given up on life. I stopped paying attention to school. I might have been 11 or 12 when this happened. I guess I had some vague notion that I would like to be a professional skateboarder, but other than that, no real goals. I didn't have any sense that I would have to do anything to achieve my goals other than skateboarding. I didn't think I would have to graduate high school. I had no real sense of the future.

The skateboarding thing was really rather a default thing because I was skateboarding and that's what I cared about. I was very unhappy about myself. I didn't think I had any value and I could not locate myself relative to any sense of the future. I didn't think I had one.

Brigid Bergin: There's a period in the book where you're in your early teenage years when you talk about experiencing depression or wanting to experience depression going through a goth phase. As you think about it now, why was it necessary to be outwardly sad at that point in your life?

Shane McCrae: Well, what I wrote in the book was I thought that it would signal to people that I needed help, but I think at the time, that's a reflection, at the time, I was just really sad, but I also thought being really sad was very, I guess, romantic. I had a very grim sense of the world and a very narrow sense of the world. I was just very deeply unhappy. I don't think any longer that that's really what goth is about, but at the time, I still love goth, but at the time I thought goth was just about being unhappy, basically. It was an artistic manifestation of unhappy feelings.

It's more complicated than that, but I was 14, 15.

Brigid Bergin: Sure. Which part of the writing process itself about your own life experiences did you find most challenging?

Shane McCrae: I'm used to writing about myself because I write a lot of poems or I try to and a lot of them are about myself. I enjoy much more writing about other people, writing about historical figures, but I do occasionally write poems about myself. That wasn't challenging. It's just something I'm familiar with. The sheer size of the book was challenging.

Writing a lot of prose is very intimidating to me and so being aware that I would have to conjure up this thing that would eventually be 200-plus pages long was terrifying to me.

The only way that I could manage it was to not think of it that way, to just write what I could on any given day and then that was the end of thinking about it in a sense unless I got really excited and something would occur to me as I was falling asleep and I'd have to write that down. It was frightening.

Brigid Bergin: How long did the process take you?

Shane McCrae: Oh, depends on how you think of it. I first started thinking of doing a memoir probably in 2003 and I finished it probably in 2022 so almost 20 years, but really intense writing was maybe two or so years.

Brigid Bergin: Wow. In the memoir, you eventually do reconnect with your father. How did his recollections of your kidnapping, the separation shift your perspective on your family dynamic?

Shane McCrae: He reified the whole thing for me in a lot of ways and he helped me to understand the depth of the wound to him and also to me because I don't have any real memories of it. He gave me a sense of what it was like, as I said at the beginning of our conversation, I just learned through that profile, through the New York Times, what time of year that I was kidnapped at the beginning of June. Which my dad told the interviewer, but I don't think I recalled that. I don't think I had been told that before. Talking with him has given me a sense of the really heavy reality of it.

Brigid Bergin: How did your family respond when you told them you were going to write this memoir and has the final work sparked any unexpected conversations with them?

Shane McCrae: I don't know that they've read it. My father's read it and he likes it which makes me happy. That makes it worth it, but there haven't been any unexpected conversations yet, and nobody responded negatively to the idea.

Brigid Bergin: How are you doing mentally, emotionally after having gone through this excavating of self to write this memoir and now having to talk about some of the most difficult parts of your life over and over as the memoir comes out tomorrow, August 1st?

Shane McCrae: That's a really good question. I'm kind of a wreck, but I think of myself as a fundamentally optimistic person, I have figured out how to be geared towards happiness. I think that this whole story if I think about it too hard, it makes me really very, very profoundly sad, but I'm happy to talk about it. I'm glad the book is coming out, and I will be happy with it if it is of use to anyone, then I'm glad that I wrote it.

Brigid Bergin: Can you say a little bit more about that, how you want this book to resonate with people?

Shane McCrae: Ever since the profile even, I've gotten contacted by a few people who've told me that similar things happen to their family members or to them. If people connect with something in it, and through that connection find a way to express something in themselves, that they otherwise hadn't been able to express, that would be fantastic, but otherwise, I just hope it's an experience. The subject matter is awful enough that it's difficult to say that I hope people are pleased by the writing, but I do hope that people think it's a good book.

Brigid Bergin: It is a remarkable achievement, and I'm so grateful that you took some time to talk to our listeners and to spend with us today. The day before your book is officially published. I'm speaking with Shane McCrae, author, and poet. His new memoir is Pulling The Chariot of the Sun: A Memoir of a Kidnapping. He has an event tonight, a conversation with Patricia Smith at Books Are Magic in Brooklyn Heights, that's at 7:00 PM. Shane, thank you so much for being here on All Of It.

Shane McCrae: Thank you for having me.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.