The Legend of NBA Star Bill Russell

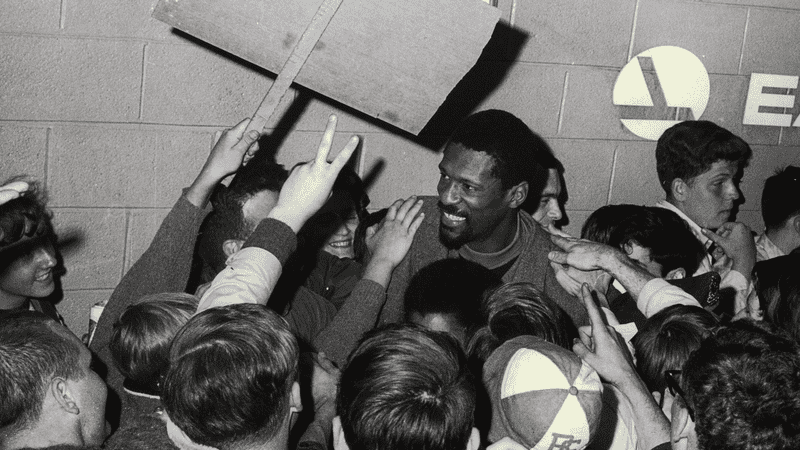

( Courtesy of Netflix © 2023 )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios in SoHo. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. In a new documentary about the life of Boston Celtics' great, Bill Russell, LA Laker great, Jerry West, now 84 years old, says, "I loved Bill Russell. He had a soul. Some people have no soul. He was one of the most unique men I met in my life. I don't say that because of his success as a basketball player, he was a leader. He was an activist when it was not proper to be an activist, at the expense of his own career." That was from someone who Russell's Celtics beat.

The film Bill Russell: Legend brings together some of the greats of the game, Bob Cousy, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Magic Johnson, Renee Montgomery, Steph Curry, Chris Paul, to tell the story of the late athlete who was admired for his work on and off the court. Born to a family in Louisiana, his family, just a couple of generations from enslavement, he went on to be his ancestors' wildest dreams. An Olympic champion, a five-time MVP, an eleven championships as a player, and the first Black head coach of the NBA. He had more championship rings than he could fit on his fingers.

He led the Boston Celtics in the late '50s and '60s to become one of the most dominant dynasties in sports history. He practically reinvented defense. He was a king of the rebound. He saw the game like no other. Bill Russell was more than just an iconic NBA player. What makes him a truly legendary human was his commitment to civil rights and calling out the racism he faced on a daily basis from his own fans at Boston's for what it was. Ugly. He could be prickly, wouldn't sign autographs, was known to throw out sharp words that cost him friendships.

The two-part documentary, Bill Russell: Legend, streams on Netflix starting on February 8th. With me now in studio is the film's director, Sam Pollard. So nice to see you in person.

Sam Pollard: Very nice seeing you too, Alison. Great to be here.

Alison Stewart: The film after the credits-- Actually, let me start back this. The film begins actually with Bill Russell's death. There's a beautiful beginning and then the credits run. He died July last year. How long had you been working on the film before he passed?

Sam Pollard: We had working on the film for about two years.

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Sam Pollard: I had been approached by the former president of HBO Sports, Ross Greenburg, if I was interested in directing this documentary, originally a series about Bill Russell, became the two-part film. I didn't hesitate. I said yes, because I grew up in the '60s. I was very familiar with Bill Russell. I was familiar with the rivalry between Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain. I was excited to jump in and do this documentary.

Alison Stewart: How did things tone? How did it shift after his passing?

Sam Pollard: We didn't have a sequence in about his passing. Immediately, we knew that we had to create a little sequence at the very beginning and also at the very end, that dealt with his passing and the fact that they was going to retire his jersey across the whole NBA. Our last interview was with his widow, Jeannine Russell, who gave us some really interesting insights about who Bill Russell is and what he meant to both players, and what he meant to the African-American community.

Alison Stewart: Yes. When he passed over the summer, we did a call in with Jemele Hill and Howard Bryant from ESPN. It was extraordinary to hear people call in about how much he meant to them. It really was beyond just him being a player.

Sam Pollard: I think the thing that hopefully comes through in the two-part films is that Bill Russell was just a phenomenal human being off the court. He was a civil rights or human rights activist. He understood the importance of standing up and speaking out. Here's a man back in the late '50s and '60s who went to the March on Washington with Dr. King, who went down to Jackson, Mississippi after the death of Medgar Evers, who was involved in the bussing issues in Boston. Who was at the Cleveland Summit with Jim Brown and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. He was a man who stood up for his principles.

Now, and it's not to say he wasn't a complicated human being, but that was another part of his personality that we wanted to really bring out and show an audience.

Alison Stewart: A moment I found fascinating was when he was first asked to be on stage with Dr. King, he declined. He declined because he felt like he hadn't been there doing the work, which I thought was a really interesting insight to the way his mind worked.

Sam Pollard: He felt politically he hadn't done enough. He'd done some stuff, but not enough, not to the same level as a Dr. King or Ralph Abernathy, and the other members of the Civil Rights Movement. That's why he felt he shouldn't be up on stage to take away the spotlight from the importance of A. Philip Randolph, Dr. King, and all the other people who were at the March on Washington, which I thought showed that he understood what his role meant in the community.

Alison Stewart: I guess Sam Pollard, the name of the documentary is Bill Russell: Legend, streams on Netflix on February 8th. There's all this great old footage. Where did you find it? What was the process of acquiring it? Just all that really good old Celtics footage. [chuckles]

Sam Pollard: The thing that's always wonderful about doing these documentaries is if you bring on a great archival team, and we had a wonderful archival producer and her team that was led by this woman, Helen Russell, who'd done lots of sports docs. She was able to do a really deep dive in finding the material of Bill at USF, Bill in the Olympics, Bill in his first years with the Celtics, and his teammates, to be able to see him with K C Jones, and Sam Jones, and Bob Cousy, and Satch Sanders.

If you have a great archival producer, he or she, or they are worth their weight in gold at helping you find the material. The other two things that we had that was important that my producer, Reuben Atlas, really said we should really dig into was taking excerpts from Bill's books that he had written. We went through those. Those excerpts from the book, that was read by Jeffrey Wright, really gives you insight into how complicated he was, both as a player and as a Black man.

He was a guy who by the '67, '68 year of his career, in 1967/1968 wasn't as excited about basketball anymore. He was being worn down, physically and mentally. It didn't surprise me as we got to that last game seven in 1969 against the Lakers where they beat the Lakers, the Celtics beat the Lakers, that Bill Russell walked away from the Celtics, walked away from the City of Boston, and walked away from his family to go on a search to find himself, which led him to Los Angeles and a whole trajectory in his life that was very, very different.

Alison Stewart: Who did you know that you wanted to talk to for this documentary? How'd you get your hit list?

Sam Pollard: We put together a long list of people with my executives. We knew that we wanted to talk to Bob Cousy. He was the first interview we did, two years ago.

Alison Stewart: He's a riot.

Sam Pollard: He's a great character.

Alison Stewart: [laughs] This is great character.

Sam Pollard: We interviewed Satch Sanders, another former teammate on that same shoot. We also knew we wanted to interview Magic Johnson. We wanted to interview Larry Bird. We wanted to interview Dr. J. We wanted to interview Kareem, Shaquille. Renee Montgomery we interviewed. We interviewed Tommy Smith, but he didn't make in the cut because we talked a little bit in one of the earlier versions about the '68 Olympics in Mexico City.

There was a long list of people. One of the last interviews we did besides Jeannine, Bill's widow, I went down to Orlando and I interviewed Oscar Robertson, which was a phenomenal treat for me.

Alison Stewart: One of the one of the things, I think it's Shaq who says it, describes about how modern-day players are like big babies compared [chuckles] to if the temperature isn't right in the hotel room, they have a fit, versus what a man like Bill Russell had to put up with.

Sam Pollard: Kenny Smith said in the film-

Alison Stewart: Is it Kenny? I can't remember who.

Sam Pollard: -back then, the things you could do as a Black man, you could lose your life.

Alison Stewart: That's right.

Sam Pollard: Kenny understood the sacrifices that Bill Russell would make to stand up for his principles. When him and his Black teammates were in Lexington, Kentucky, and they refused to play because they weren't going to be served in hotel, that said a lot about who Bill Russell was. Even someone like Earl Monroe, who we interviewed, said players back then didn't usually take stances like that because it could have recriminations that could hurt your career. You got to really admire Bill. You look at what happens today with players like LeBron and Chris Paul, they're standing on the shoulders of Bill Russell.

Alison Stewart: They understand that.

Sam Pollard: They understand it. What's interesting to me is when we interviewed Steph Curry, I was very impressed that Steph had even read Bill's autobiography. He knew exactly what Bill Russell was all about. A lot of these young players may not know the level of importance Bill played in the evolution of the game, but they saw Bill Russell because he would always be at those NBA finals because they named a trophy after him. He would be there.

They knew who he was, but they didn't quite know the legacy that he had, the rich, important legacy. You talk to young people today and you say, "Who's the greatest basketball player of all time?" Usually, the discussion is LeBron, Michael Jordan, but you got to put into that discussion, Bill Russell and even Wilt Chamberlain.

Alison Stewart: For sure. My guest is Sam Pollard. The name of the documentary is Bill Russell: Legend. In his life story, born in Monroe, Louisiana, grew up in a segregated neighborhood, just, like I said, a couple generations away from enslavement. His family decides to leave when they're nine. They hop a train to California. How to being part of a, Isabel Wilkerson calls them the sons of the great migration, what impact did that have on the way Bill Russell moved in the world?

Sam Pollard: Well, here's what I would say. His family moves to Oakland, and he has an opportunity to go to a school where he's able to shape his athletic prowess in his career. He's at a school where a lot of African-Americans had migrates Oakland and their off-springs also became athletes. If you look at the people who came out of the school that he went to McClendon, Frank Robinson, Veda Pinson, Curt Flood, Bill Russell, that's pretty phenomenal that these athletes came out of that they became out of the [unintelligible 00:10:45] that migration.

The migration for those of us as African American families who believe that the sense of possibility would be greater leaving the south. Now didn't always work out that way, because de facto segregation existed in these northern enclaves. It was the dream that Black people had.

Alison Stewart: Bill Russell settles into his new life. Let's listen to a clip of Jeffrey Wright narrating Russell's memoir regarding his love of the library as a child.

Jeffrey Wright: I had my own private world, and my most prized possession was my library card from the Oakland Public Library. I went there almost every day, I check out reproductions of paintings and take them home with me. Prints of Da Vinci, Michelangelo. Those paintings helped me spellbound. I would study in Michelangelo for hours trying to memorize each little detail. It took me weeks before I was satisfied that I could close my eyes and recreate anything resembling what I saw on the reproduction. Then I would psych myself up for an acid test, drawing the painting from memory, the result always frustrating.

Alison Stewart: That becomes so interesting because it becomes important to the way he would play the game to towards his basketball IQ, that he could envision things on the court. Tell us a little bit more about how that time of his reading his love of painting, his love of art seeped into the way he played ball.

Sam Pollard: Well, he understood that the game of basketball is just not about being physical, it's about being mental. It's about understanding how to position yourself and play against other players, where you should be where one of your teammates should be to get the ball to take it down to court to get a basket, to know when to get a rebound and where to get the rebound and how to use that. When he was at USF with his future teammate, K.C Jones, they came up with the strategies. That's what they would call themselves rocket scientists.

They were really thinking about the physics of basketball. It just goes to show you that athletes are very intelligent people, they're not just jocks, they're very intelligent. Bill took it to another level in terms of understanding the science and the physics of the game and how to use the game to his advantage. Think about it this way Allison, when he would play against Wilt Chamberlain, he was 6'9 will change 7'2, Wilt Chamberlain had 30 pounds on Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain could out-score him, he could probably rebound him.

Bill Russell understood that if he strategically knew how to contain Wilt Chamberlain just to a certain degree, he can help his teammates get baskets and win games. As [unintelligible 00:13:36] says in the film, it wasn't about how many points a player would score, it's about who would win the game. You look at the stats, the Celtics always were on top when it came to playing against any team that Wilt Chamberlain was on.

Alison Stewart: I was so interested in the idea of Bill Russell being able to jump high, and how that just changed the way people thought about being a defender. The time I grew up of course you would do that, but that was considered rad, at the time.

Sam Pollard: It was radical, because you're supposed to keep your feet planted. All of a sudden, you become vertical and you go up, people were telling him that was the wrong way to play the game that's what he was hearing from his coach at USF the wrong way to play the game. Something that Nelson George says in the film, which I think really pinpoints the importance of Black players in the evolution of the NBA was that when Oscar Robertson, Bill Russell, Elgin Baylor, came into the game of basketball, they brought with it the Black athletic aesthetic, a new way to approach the game.

You're going to see that with Black players in football and baseball, when they bring that skill to those games it changes the whole the way you approach the game, and has elevated every one of those sports.

Alison Stewart: Following up on that point, the NBA was all white.

Sam Pollard: All the white. There were barely any Black players in the team.

Alison Stewart: It's wild.

Sam Pollard: When we Bill Russell's talking about playing his first game against the team that Bob Pettit was on, and the crowd was yelling things, "Don't get there because, he sue chocolate." He was the only Black man on the court. You could see that he had some mountains to climb but by the mid 60s, the game was evolving and changing, and it was definitely as we all know, basketball is a Black game.

Alison Stewart: Name of the film is Bill Russell: Legend streams on Netflix, February 8th, I'm speaking with his director, Sam Pollard. You brought up Wilt Chamberlain, the press called them rivals, I think Bill says no, they were just competitors. What did you observe after really thinking about the way these two men had to interact with each other, engage with each other? What was the relationship?

Sam Pollard: I think it was a relationship they were competitive. I think what Bill Russell understood was, he was a man in terms of Wilt Chamberlain, who was phenomenal, a phenomenal ballplayer. He was a man that I had to figure out how to play against and to figure out how to control my sense of play against his sense of play that would help my team. Bill Russell understood that even though Wilt Chamberlain could score 100 points a game, he could have more rebounds in the game, he was not a team player. Bill Russell understood that, that's why he had 11 championships in 13 seasons, what did Wilt have? Maybe three championships and all of his years? Bill Russell understood that.

What was interesting about that dynamic was that when the Celtics will come to Philadelphia, Chamberlain would have Russell come to his house to have dinner. Most players wouldn't do that. They would sit down and have dinner and hang out, but then when they go to play, Wilt Chamberlain mother will always say to Bill Russell, "Don't beat up on my son too badly." That day you would have to worry about Bill Russell beating up on Wilt Chamberlain.

Alison Stewart: We have to talk about Boston, Bill Russell once said, "I played for the Celtics. I don't play for Boston." Boston has earned its reputations in many ways, a very racist city. While he was a Celtics player, how did he feel about wearing the jersey? How did he feel about-- given how poorly some of the fans behaved?

Sam Pollard: He always said he was a Celtic. He loved being a Celtic. He loved wearing that green, but he didn't love the Boston fans. Think of it this way. Here he comes, he really becomes the linchpin in the mid to late 50s of the Celtic team and the Celtics fans even when he starts to be the one to help the Celtic players win championships, who do they think the greatest player on the Celtics is? It's not Bill Russell is Bob Cousy who's called the Houdini of the hard way.

Bob Cousy understood the difference because Bob Cousy says in the interview, "I was the man before Bill Russell came on the scene, and when Bill Russell came, he became the man, because he became the linchpin that turned the Celtics into a dynasty." The Celtics fans never embraced him, and the sad part is that when him and his family moved out to Reading, Mass, they were not welcomed with open arms. The story that when they left, they were on a trip, somebody broke into her house and you defecate in the family bed and wrote on the walls and destroyed the house.

You could see why Bill Russell had a chip on his shoulder about the Celtics fans, why he wouldn't go and beyond him initially when they want to honor him and retire his number. In some ways as he got older, like a lot of us he mellowed so that's why near the end of the film, you see him go to that ceremony.

Alison Stewart: Let's listen to a clip from the film Bill Russell: Legend. This is a clip of Russell speaking about his role as a Black athlete after being asked by a reporter.

Reporter: Do you think the new Black athlete can collectively bring about any social or political change?

Bill Russell: I can say things that I did, I said over the years, it's because I had a position of power, and that I was very good, but converse that made me have more to lose, in the sense of what they were talking about but it was nothing to lose to me because if I don't have my manner, they don't have anything, athletes or products rather than people.

Alison Stewart: I got that sense in the film not only did he feel a responsibility, he also felt it very personally, I took away from this film that Bill Russell was actually an emotional man.

Sam Pollard: Oh, extremely emotional, extremely sensitive, and you can see it through everything he did. Every sentence of those autobiographies you can feel the sensitivity he had about being a Black man in America. About the responsibility he had to stand up. He just didn't want to shut up and dribble. He wanted to stand up and have his voice heard. I think he's a very emotionally human being.

Alison Stewart: When he was first offered the opportunity to be a coach, Bill Russell refused at first. What was behind that?

Sam Pollard: Well, I didn't think he felt he had the ability to be a coach and it was going to be a lot of responsibility to coach a team and also be a player. Then he realized when Red Auerbach was making certain suggestions that besides Red Auerbach, the only person who could coach Bill Russell was Bill Russell. Imagine this back in that period 66, 67, 68, 69 he didn't have what coaches have today a bunch of assistant coaches and trainers and all that stuff. He had to do everything and also play. It had to be really tough. Chris Paul even said that, "I don't think I could do that," and so did Steph.

Alison Stewart: You mentioned earlier how he got worn down and he decided to leave the game. What did he want to do when he went to the West Coast? It seemed like he was actually trying to pursue a little bit of fame and fortune, but it didn't seem to be the ill-fitting suit to me when I watched him going down that road.

Sam Pollard: He was trying to figure out I think how could he turn his sports celebrity into something that was going to be much more lucrative. Probably because he was really close with Jim Brown who had done that. Jim Brown had left the Cleveland Browns to become a pretty well known actor. Making lots of movies and becoming a star to a certain degree. I think Bill and somewhere in his mind look for that. You saw that little clip we have where he's in Miami Vice. He's terrible.

Alison Stewart: He's really bad. [laughs]

Sam Pollard: He's doing commercials. He's on the Flip Wilson Show, he's on doing all these shows. He's trying to figure out, he was searching for what's the next step for me after this illustrious basketball career. I think he may have never found the same satisfaction he had as a basketball player. He became a coach of the Seattle Supersonics and the Sacramento Kings. He was successful with one team but not so successful with another. He ended up moving to Washington State. I think he was still a young man so he was looking for something else in his life.

Alison Stewart: The film also talks about the Bill Russell laugh. That laugh was such a signature, and it was also such a icebreaker in a way. [crosstalk] When you think about how intellectually strong he was, how emotional he was, and then this goofball laugh would just pop out.

Sam Pollard: Yes, for sure. He was human. That he could open up to people. With that little montage where you hear that cackle of his, and it broke the ice. It enabled him to slowly say, ah, take a breath. He also had the other thing where before every game he would vomit because it was like superstition. If he didn't vomit maybe the Celtics wouldn't win. He had these little ticks that were part of his personality, and then he's famously known for not signing autographs.

He wouldn't sign autographs. He felt like it was more important to talk to a fan than to sign a piece of paper. Now when I mentioned this to Steph Curry, when we interviewed him which we didn't put in the film Steph didn't quite understand why Bill Russell wouldn't sign autograph because for him as a major sports celebrity that's part of his responsibility to sign autographs. Bill didn't feel that way, not even with his teammates.

Alison Stewart: What something that his daughter told you that was really useful for you in making this film whether or not you used it or not but it was just some piece of information that really was helpful.

Sam Pollard: I think the most poignant thing that she told us was how much she loved her father. The father daughter connection was very strong. You could see that she felt this real bond with her dad, that comes through every time she talks about him. That father daughter connection.

Alison Stewart: The name of the film is Bill Russell: Legend. It streams on Netflix starting on February 8th. I've been speaking with its director Sam Pollard. Sam thank you for being with us.

Sam Pollard: My pleasure Alison. Enjoy the rest of your day.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.