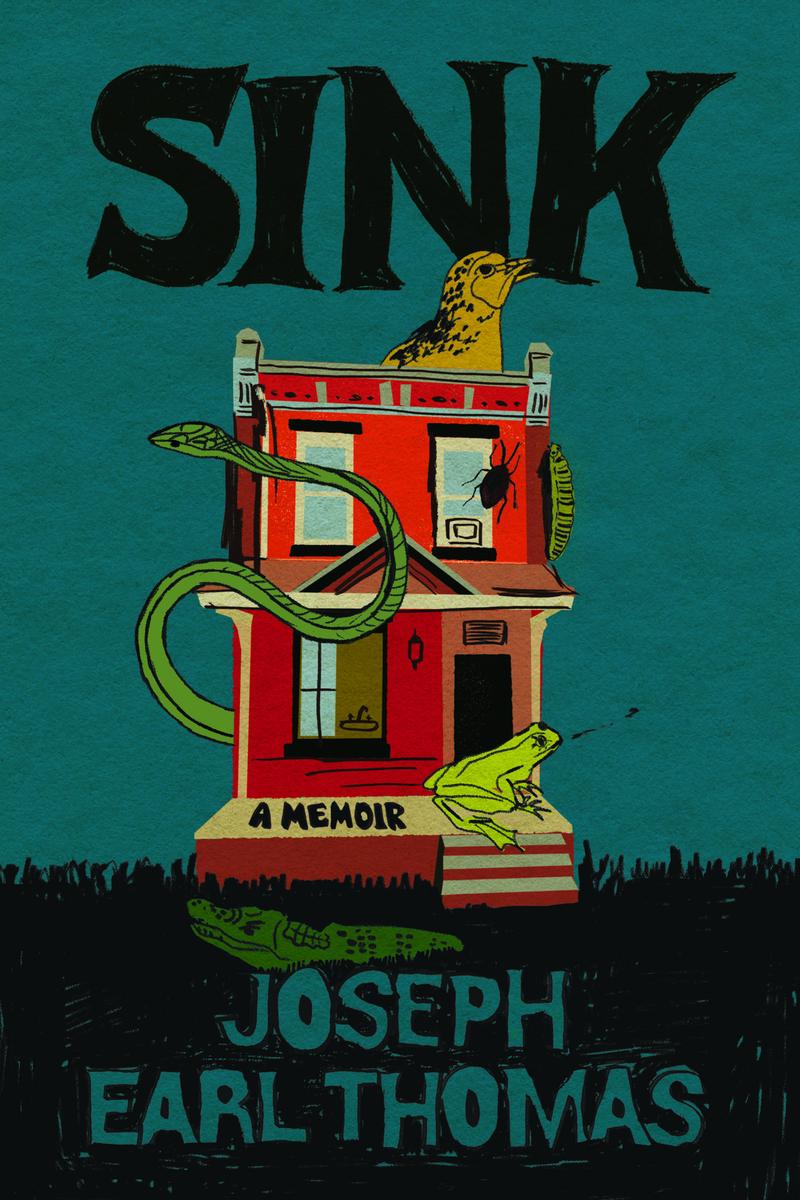

Joseph Earl Thomas's Debut Memoir 'Sink' Is a Difficult but Tender Story of Black Boyhood

( Courtesy of Grand Central Publishing )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. The first line of Joseph Earl Thomas's heralded new memoir titled Sink lets the reader know, this retelling of a life will deviate from tropes. It reads, "Of all the protagonists in this story—both real and imagined—just Joey, the boy, owned an Easy-Bake Oven."

The time and place are North Philadelphia in the 1990s, and we're introduced to this family that consists of Joey, who also loves video games, watching anime and exotic animals, his little sister Mika, and later his little brother Juju. They live in the basement of a house that belongs to their stern grandfather Popop, who has an attitude, smokes a bunch, and isn't really their blood relation. He is married to their sometimes affectionate grandmother known as Ganny, who seems to go from kitchen to bedroom to kitchen to bedroom and that's about it. The kids' mother, Keisha, has substance abuse issues and comes around every once in a while.

In the book, we watch as Joey lives his life. No big grand gestures, no real saviors. He is a kid surviving his circumstances and reacting to what life throws at him. Kirkus Reviews said of Sink: A Memoir, "It takes rare courage to tell a story this harsh and unredeemed."

Joining us is Joseph Earl Thomas. He's an associate faculty member at The Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, as well as Director of Programs at Blue Stoop, a literary hub for Philly writers. Joseph, are you still pursuing your PhD at UPenn?

Joseph Earl Thomas: Yes, indeed, I am.

Alison Stewart: Okay, keep going. Nice to meet you. [chuckles]

Joseph Earl Thomas: Hey, nice to meet you too.

Alison Stewart: A lot of memoirs give us the cradle to the grave, or near-the-grave or later-in-my-life kind of stories. What interested you about really focusing on you as a kid, Joey?

Joseph Earl Thomas: Yes, that's a good question. In most of the work that I read or have read, I'm most interested in the way that we try to explain the lives of children, whether that's ourselves, or explaining children through the lens of being an adult. I'm also interested in one of these tropes that occurs where we read about the life of a 20-something or maybe early 30-something person, and the only time where we go back into that perspective of childhood is when we want to explain away or towards maybe some fault or something that the adult person is doing wrong. Maybe they're in therapy, or maybe they're making certain kinds of mistakes that are then placed in a one-to-one relationship with some particular thing that happened when they were a child.

I always thought, what if we linger in the spaces of childhood for a little longer as if those things are important in themselves, and not just a backdrop or a way to understand our adult decisions? In part, because for a lot of us, those are the experiences, those are sometimes the only experiences that we have. If I'm reading correctly, to some extent, those are the experiences that we think of as being fundamental to who we are. That's the thing that we all share too. Everyone has some kind of story relationship about being a child, but for the most part, it's always piecemeal. I wanted to expand that as much as I could.

Alison Stewart: What is something you know about writing a memoir that you just couldn't possibly have known without writing one?

Joseph Earl Thomas: [chuckles] That it is difficult to stay in the frame of one position or part of your life. You said the cradle to grave thing before, which is also a great movie, classic. I found it really difficult, and this was a challenge I posed to myself, to stay in the perspective of my 8 to 12 or 13-year-old self, rather than constantly imposing my adult self that knows many more words or explanations for things in the world, et cetera. I found that very, very difficult, but it was something that I wanted to be deliberate about.

Alison Stewart: Yes, it's interesting that Joey, who we're following, says things like winkie to describe a male organ.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: He's got the vocabulary of an eight-year-old. That's such an interesting idea, that you have the brain of a grown man, but you have to put yourself back to thinking how an eight-year-old would respond to all its different stimuli.

Joseph Earl Thomas: Yes.

Alison Stewart: When you look back on that kid Joey, what was interesting to Joey? What interested him on a daily basis?

Joseph Earl Thomas: There were so many things. One of the things that I think about with coming from child to adult, and the things that we lose that are maybe not physical things always, are a certain kind of import of imagination or curiosity, I think. Particularly when it comes to young boys, some of the first things that are beaten out of us are your interior life. You're sitting there, you're daydreaming. You're valuing your imagination more than the material world and making your body strong and learning how to protect, defend or fight or whatever. Those aren't things that you're supposed to do, and those definitely weren't things that I was taught to do or taught to honor.

As a kid-- Ursula Le Guin has this really good essay about this called Why Americans are Afraid of Dragons, that at least in some ways relates to this question that I'd love to go back to, but I was, to some extent, interested in everything. I watched a lot of anime, I loved music, I loved video games, animals. I watched a lot of Steve Irwin. This is something that comes up a little bit earlier. The whole Animal Planet regime was coming into being around that time, prior to like those big Planet Earth documentaries. I was super invested in all of that. I was also interested in paying attention to what other people were doing with their bodies, and what maybe things that they wouldn't say or talk about as directly.

As I got older, I realized, or I tried to pay attention to the ways that I was being taught not to have an interior life that was as expansive and to narrow that down. Perhaps this happens in ways that are like, "What are you going to do when you get older? What do you want your job to be?" Teachers ask this or are taught or told often to ask children, "What do you want to be when you grow up?" And it's a firefighter or whatever. I'm like, "Oh, there's all these other things to think about." I was trying to be like, what is it that I was interested in prior to work, prior to labor, or joining the capitalist workforce or whatever, and those were the things that I wanted to stay close to.

Alison Stewart: You don't tell us. You show us that you felt you had to keep some of this secret because you had this little black notebook that you hid it. How did your young self know to hide it?

Joseph Earl Thomas: I think there's only about one instance in the book itself where I'm "caught" reading something and get yelled at about. That is seen as a certain kind of trivial pursuit. Go do your chores. Do something with your body. Go and cut the grass or shovel snow, or whatever. Make some money. Participate in the external world and all of these ways, and not do that interior stuff.

For me, I knew that if I was not even supposed to be reading things, and that was an unserious or too feminine of an activity to do, there was no way that I was supposed to be writing things, and in particular, not the kind of things that I was writing or drawing in that notebook, a lot of which were these really violent, childish, revenge fantasies as well.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Joseph Earl Thomas. The name of the memoir is Sink: A Memoir. Why Sink, the title?

Joseph Earl Thomas: There's so many reasons. The first one is, of course, maybe the most direct: allusion. Which is this relationship between sinking and buoyancy in relation to a lot of stereotypes about Black people not being able to swim, despite the fact that I didn't learn how to swim as an adult, which had to do with a lot of structural stuff. I wanted to play with that idea as an initial entry point, but the physical material part of the title has to do with the sink that was in the place where I most prominently grew up, where one of my chores was to clean the kitchen.

That meant doing the dishes first and mopping the floor and wiping tables, put all the food away, et cetera, but this sink was always, it felt to me, just filled with all this gunk and clutter, and just ridiculous stuff that shouldn't be in the sink, like a half-empty tuna can or something. One of the things that comes up in the book is, why is a whole chicken skeleton basically in here? Things that just feel slimy that you can't identify because you can't even see underneath the water because it's too murky.

I'm using that as a structuring metaphor to think about all of the things that you don't know and that you don't know you don't know as a child, and how frustrating and confusing the whole process can be, especially when you don't necessarily have a good education system or a safe education system, or a group of stable adult people to tell you things or to take the time to describe the world to you in ways that would be less confusing directly. I thought about that. Even though it doesn't come up until later in the book, I was thinking about that during the entire process of writing.

Alison Stewart: I kept thinking about it being the- they say, threw everything at you, including the kitchen sink. [chuckles] [crosstalk]--

Joseph Earl Thomas: Yes, exactly. That's another one. There's so many. [chuckles]

Alison Stewart: This kid has got so much coming at him. The name of the memoir is Sink: A Memoir. My guest is Joseph Earl Thomas. We'll have Joseph read from his memoir after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest this hour is Joseph Earl Thomas. The name of his memoir is Sink. People who are thinking like, who-- We've been talking about Joey. You are Joey. [chuckles] You are Joey, and you wrote this in the third person. What did that open up for you as a writer to write your memoir in the third person, third-person eight-year-old third person? [chuckles] [crosstalk] Eight to teenage.

Joseph Earl Thomas: [chuckles] Yes, a couple things happening. I was super interested in the question about what it takes-- Of course, there's a lineage of thinking about this, particularly in 20th-century African American letters, about the becoming of a subject on one's own terms, and what it would take for that to happen, particularly without the prying of white eyes. As a formal experiment, I was thinking about what are my earliest remembrances, or what are some of the earliest time where I felt most like a person or someone who I could say, I did this, or I want, or I feel, et cetera, and that wasn't necessarily when I was at around that age. It wasn't necessarily when I was around eight or so.

The third-person can be really useful in this- what we would call free indirect discourse and novels or whatever, can be this real interesting thing to trying to do this subjective and objective thing at the same time. Also, for simultaneously being in an interior space, and making all these queries about the things that are around you without always turning into exposition. I didn't want to write a long essay, and I didn't want to break into essays while I was working through this.

Settling on moving through most of the book in the third person, and eventually it goes to second too, helped me to break down the relationship with the barrier between what it would take to become a first-person subject and to be able to explain everything, to know everything, to have the pressure of knowing and being everything in the world, and this other part of me that was like, "I don't exactly know my place here or how all of these structures work, but I'm trying to figure it out." I wanted the whole book to read like or to feel like a story that is doing that, rather than a person who has the capacity will or ability to explain that process in terms of exposition.

Alison Stewart: Would you mind reading a little bit for our audience so they can get a sense of-- We talk about home and family a lot, you talk about home and family a lot, but you take us to life at school, which involves other kids too. Page 81, as contained--?

Joseph Earl Thomas: Yes, of course. [excerpt Sink: A Memoir page 81] As contained as the schoolyard felt when the gates were locked, there was a child-size hole on the far end of it that among other things, the teachers never seemed to notice. The hole was important, and sometimes Joey showed up late and walked through it into school instead of through the gate with the other kids. There were big gray metal doors that were hard to open, like they were made for Minotaurs or something, leading to his third-grade classroom. The school looked like it should have metal detectors, but didn't yet.

Outside, all the kids lined up in size order waiting to enter while taking off their jackets. As tall as a middle-schooler already, Joey brought up the rear. In the classroom, he put his coat on the floor beneath the others because there was never any more hooks. He was annoyed though because it had a little hole in the arm that he kept trying to tape shut. It spilled fluff haphazardly. He learned how important it was to find the most inconspicuous seat in the room anyway. Even though he imagined that sitting up front was more conductive to learning, it was too risky.

The tall, lanky kid in front of class with the bowl cut, the huge gap between his rotted front teeth and clothes that smelled of urine was too easy a target. Even Joey hated him. God forbid the roaches crawled out of his jacket or book bag again. The little brown bodies scurrying across the white classroom floor were hard to miss. But Joey thought that if he could go without incident for a week or two straight, maybe some kids would forget.

Alison Stewart: That was Joseph Earl Thomas reading from his memoir, Sink. How do you remember those details?

Joseph Earl Thomas: One of the rules that I made for writing this book, which is related to a whole host of other literary conversations about what is gratuitous, what is not gratuitous, especially with regards to violence and representation, et cetera, was that if something didn't happen multiple times, I would excise it as quickly as possible from the book. A lot of the things that do occur that I write about were repetitive, and so repetition becomes super important in the book in a lot of ways.

This was just a consistent- it was a very constant problem. It's one of the earliest ways that I remember trying to maneuver in certain spaces, or trying to comport my body in ways that would make me less obvious or would bring me less shame or become less noticeable because there was always a certain threat that one would be found out and the shame would come washing over again and lead to certain kinds of violences.

Alison Stewart: In the writing process and in the editing process, how did you keep yourself from just getting-- Sometimes certain things can bog you down. You can get lost in a story, you can get lost in a moment, you can get lost in an emotion. Just in a practical way, as someone who's got to write a book that has a pace and that people are going to read, how did you keep from getting stuck?

Joseph Earl Thomas: Yes, that's a really good question. I will say, this book took shape maybe over the course of around eight or nine years. Not all of which I was writing intensely for hours every day, but all of which I was working on in some capacity. I think that that helped, that it took a long time. That was one thing.

The other thing was that because I live in Philly still and I've lived there for most of my life, it wasn't abnormal for a lot of the conversations that I'm having in the book to be occurring all the time in my adult life. I'm talking to my grandmother, my mother, my grandfather, my brother, sister, et cetera, friends on a regular basis. That shared experience, or the fact that we all knew that we all knew and that we do have remembrances of these events, made it a little bit easier as well.

Then as a formal problem, I enjoy a short chapter, I enjoy a vignette, and I feel like they do a lot for me with regards to pace. This is especially true with going into vignettes that are purely in the mind or in the imagination. There's a lot of small breaks in the book that do that, particularly after a more weighty chapter. Even though I think the chapters tend to be shorter in here than in most books too.

Alison Stewart: The book has details. Some of them, sometimes it's funny. It's often harrowing. It's difficult subject matter: your mother's substance abuse, sexual exploration, maybe sexual exploitation. Did you have any personal ground rules about what you would put in and what you would leave out?

Joseph Earl Thomas: Yes, I did. If somebody told me, "Absolutely not, do not put that in there," [chuckles] I would not put it in. I would not do that. Of course, there's a kind of general memoir conceit that we have by either not using or changing people's names as well. That makes things a little bit easier and tries to avoid certain kinds of harassment that can happen as well from that aspect.

I also had this thing where if it wasn't part of a collective memory through groups of folks that I am still in constant contact with all the time, I might elide it or not give it as much focus or attention. Then I also had, to some degree, trust in my editor, in combination with these other things, to say, "Okay, how do we define what is gratuitous, and how do we define what is necessary to tell the story?"

Because quite honestly, the things that were most difficult for me to write about had to do with sex or sexual exploitation or exploration that I was avoiding for a long time, at first because I didn't want to include other people and force them to have to deal with it, less because of me. Eventually, I started talking to my aunt, I started talking more to my mom and other folks, and being like, "Do you remember this? Do you remember?" Folks did. They were like, "Oh, I remember exactly this."

We know that particularly in lower socioeconomic class like Black communities, sexual violence is much, much more common than in a lot of other places. There are all these kinds of established rules for how we talk about it and when and under what circumstances. I wanted to be true to, of course, on the broadest level, what is actually happening, while also not doing things just for play or show or for fun. I think the last thing I'll say about this, when I talk to my mother or grandmother or grandfather about their experiences as children, they make my experience as a child look like Sesame Place every day and night.

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Joseph Earl Thomas: Which says a lot to me about what kind of things are possible, or what things I think are worth talking about or exploring or taking time to sit in.

Alison Stewart: What was it like for you as an adult walking around as you are resurfacing some of these difficult moments, some of this really hard stuff? You can sit down and write about it, and then you got to go live your life as Joseph, and go to the grocery store and talk to people and get your assignments in.

Joseph Earl Thomas: Yes, so there's two things. I think maybe people find this part strange, in that I never felt detached from my experiences, mostly because I never detached myself from my friends and family who didn't go to college, who never got to the point where they had stable housing or stable work or a stable relationship to healthy food, et cetera, and all those things.

What I think we're prompted to think of as concerns of one's past were actually super present for me because every day, I'm talking to my mom or my sister or my grandfather, who actually just passed not too long ago, or a bunch of friends whose daily experiences are exactly the same as mine were in this particular text. There wasn't a lot of re-dredging up a lot of experiences. It was just a consistent continuation of those things.

I think this is also true because my longest-held adult job was at a hospital. I worked in an emergency department at Einstein Hospital in North Philly, and I would see a lot of people that I grew up with, that I went to elementary, middle school with, et cetera, coming into the hospital. Same exact stories or very similar as mine, and we would be talking about those, and I would be in a position of power over them, and also intimacy, when you're at a hospital. It was just impossible for me to forget. I never got to the point-- It is jarring because at this time, I'm at UPenn, and also in a situation where [crosstalk]--

Alison Stewart: Hold on. WNYC, and my guest is Joseph Earl Thomas. We're talking about his memoir, Sink. In our last moments-- That's interesting. You were saying that you didn't submerge it, you didn't walk away from it. This is your life and it's part of your story. It's part of your story whether it happened then, it's part of your story today.

Joseph Earl Thomas: Yes, it continues on, and moving between and within those spaces is something that I still consistently do all the time. There's a work life that is not necessarily comprehensible or important to the people that I grew up with or my family, and then there's my actual experiences of life of coming into being that would not matter even the slightest bit to people that I work with. That's just something that I constantly think about.

Alison Stewart: The name of the memoir is Sink. My guest has been Joseph Earl Thomas. First of all, congratulations on the memoir. Really appreciate you taking the time to talk to us and be so candid about your story.

Joseph Earl Thomas: Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.