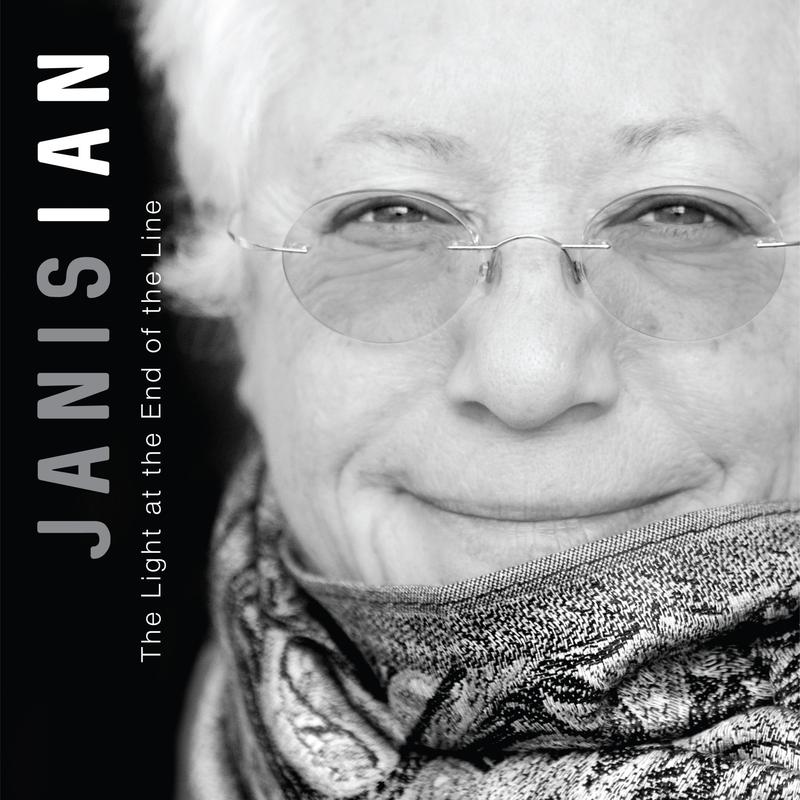

Janis Ian's Last Album, 'The Light at the End of the Line'

( Courtesy of Janis Ian and United For Opportunity )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. We continue our Grammy week coverage with a veteran nominated this year 55 years since her first release in 1967, Janis Ian's final solo studio album, The Light at the End of the Line is nominated in the best folk album category. This week it was announced she will receive the Lifetime Achievement Award at this year's Folk Music Awards. Janis Ian has been writing meaningful songs for decades. She spoke to generations of young people who felt like outsiders with her hit, At Seventeen, from her 1975 number-one album Between The Lines.

I learned the truth at seventeen

That love was meant for beauty queens

And high school girls with clear-skinned smiles

Who married young and then retired

The valentines I never knew

The Friday night charades of youth

Were spent on one more beautiful

At seventeen I learned the truth

And those of us with ravaged faces

Lacking in the social graces

Desperately remained at home

Inventing lovers on the phone

Who called to say, "Come dance with me"

And murmured vague obscenities

It isn't all it seems

At seventeen

Alison Stewart: At just 14 years old, Janis Ian burst onto the scene with the hit 1967 song Society's Child about the love of an interracial couple. She faced backlash because at the time interracial relationships were taboo and could even be dangerous. Now in her early 70s, Ian is as outspoken as ever. She released her nominated album in early 2022, and join me for a listening party. Listeners, Janis was kind enough to take calls for this segment, but this is an archived conversation so just a reminder, we can't actually take your calls live today. I started by asking Janis when she started working on her now Grammy-nominated album.

Janis Ian: Depending on how you look at it, 14 years ago, or just a couple of months, I turned in The Light at the End of the Line, which is the title song I wrote that two weeks before we went to master the album. I'm still standing, I started literally with the idea for the title in Australia, maybe 14 years ago. A work in progress for a very long time that COVID for all of its horror actually gave me time to finish.

Alison Stewart: When you were thinking about when you first started this album in assembling it, did you know it was going to be your final studio solo album, or did that reveal itself?

Janis Ian: I would say it revealed itself the closer I got to 70 which to my astonishment I am. The closer I got, the more I thought, "What do I really want to do with the rest of my life?" I know it's a cliche to say, "You can die at any moment. You can get hit by a bus," but somehow when you hit your 70s, it becomes much more real than it is in your 20s.

I thought what I don't want to do for the rest of my life is beyond what I call the wheel or the merry-go-round, the circus of make, an album, go on tour for six months, prep for the album, make an album, and go on tour for six months. The only way to do it in my industry is to stop. You can't be on the road and then be home and be on the road and home. I decided about two years ago that 70 was a good age to stop.

Alison Stewart: You mentioned that one of the songs which we'll hear a little bit later was written 14 years ago. Which songs in the album-- Were there any songs in the album I should ask that were written specifically once you realized this was going to be your last solo studio album that were written specifically with that in mind?

Janis Ian: Absolutely, Resist. Because there was a point in the writing of this album where I thought I am really really tired of people saying, "God you're a great guitarist for a girl. God do you know you've got so many Grammys for a girl." I've been hearing that since I was 13 years old and I tried to join my first band and they said, "Wow, you play satisfactions guitar great but you're a girl." I felt like saying, "I knew that already. Why didn't you guys notice till now?" For me, writing Resist in part was okay, this is my statement. This is the At Seventeen, that I would have written now.

Alison Stewart: You just teed that up so nicely those were the next two clips I was going to play. Thank you, Janis Ian. I want to start with-- I actually split it into two parts the song Resist because the top is spiky and it's different from the rest of the song. The song is quite a musical journey. Let's play the top of Resist and talk about it a little bit. This is from Janis Ian.

She is. She is. She is.

She is. She is. She is

She is. She is. She is

too short too fat too skinny

Too tall too plain too pretty

Too hot too wet too sticky

Too... picky

Alison Stewart: All right, tell me about writing those first 56 seconds of the song. How does it set up the rest of the song?

Janis Ian: Basically what boys talk about in locker rooms. You start out with she is, she is this and she is that and she is this and she is that and boys are stuck with that. They're stuck having to look cool in front of their friends. She's too wet. She's too hot. She's too sticky. She's too pretty. She's not pretty enough. She's all of these things that we are never quite right until somebody gets us and then we're fine for a while, and then we're not. That was a big part of this that opening with the guitar and that thud that Randy Leago put in there which to me sounds just like the heavy footfall of somebody who doesn't mean you any good. Your right, the song is in pieces, it required being separate elements.

The next element goes into put her in high heels, carve up between her legs, some very ugly things that again I found very uncomfortable to talk about, but they were necessary to the song. I think that was the big decision on this album. Do I be polite or do I do what the song requires? That's always the hard choice. On Resist that I tried to do with the song itself required

Alison Stewart: Let's hear another section of the song Resist when it really starts to pulse and rock there's some good homework in here as well this is Resist.

Tell me that my body bears a permanent stain

Tell me we can marry if I give up my name

Call me your baby so I never grow up

Tell me you love me when you only want to fu-fu-fu-

Funny how I whisper and you think it’s a roar

You ask me to the table then you seat me on the floor

You want me to be sexy. You want me to be pure.

I cannot be your virgin and I will not be your whore.

Resist. Resist resist resist.

Resist. Resist resist resist.

Alison Stewart: That's Janis Ian's Resist from her new album The Light at the End of the Line. Tell us about the band on the song what you guys are going for.

Janis Ian: The band is me and Randy Leago who is absolutely brilliant. We've worked together now for about 20 years. He's an incredible player and this was all done long distance during the COVID lockdown. I recorded my guitar part and then a vocal and I sent it to Randy and from there it was, "Okay, what would you think here?" "No, I think that we should have just a really nasty-sounding drum." Then, "What do you think here?" "Well, I love the stones, but I hate women being called bitches and whores, so let's do a shout-out to the stones with this axis."

A lot of it is Randy's sense of what it would be like to be a woman constantly having to think, "I need to cross the street because there's a group of men coming at me. I can't get on the elevator because it's filled with men." Things that women think about that he knows from his daughter and his former wife and his current wife and for me and he very boldly stepped in there and said, "Okay, whatever you want let's do it."

I said, "Then let's go for broke. It's my last album. I don't care what people think. I just want to do what's right." Big shout out to Society's Child with that Oregon sound because it's the exact same Hammond B3 sound all over Society's Child. I love those two lines. The lines that I love in the song most are, "You ask me to the table, then you seat me on the floor." Who has not had that happen? Of course, we want women to be part of this, and we're inclusive. Can you get me a coffee?

Alison Stewart: Right.

Janis Ian: That and the, "I cannot be your virgin and I will not be your whore." That was the hardest line to come up with because I really wanted to talk to men because men are half the world and we have to do it together. Women can't solve this alone. Men have to be a part of it. Bell Hooks said, "Education was the key for feminism, and you can't know that something's wrong until you know it's wrong." To say to a man, "I cannot be your virgin. I will not be your whore." That's a very clear definition. I tried to make it a definition and not a challenge.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Janis Ian. Her latest album is called The Light at the End of the Line. Our phone lines are full of people who like to [laughs] say, hello.

Janis Ian: That's encouraging, isn't it? Its horrible when no one calls.

Alison Stewart: Yes. Let's go to line one. Can we go to Cheryl calling in from Tewksbury, New Jersey? Hi, Cheryl.

Cheryl: Hi, Janis. It's a thrill to talk to you, and I'd like to- [crosstalk]

Janis Ian: Oh, thank you.

Cheryl: -brag that when everybody talks about the first record they ever bought. I know I took my babysitting money and I'm guessing it must have been 1970, I would've been 13, and I bought Society's Child.

Janis Ian: Oh, wow.

Cheryl: Not only did I love the song, I lived in a suburb of Detroit, which was a couple of years after the riots. They integrated my school and it gave me the courage to invite a Black girl home for my math class to do homework with me. I don't know if I would've done that if it wasn't for your song.

Janis Ian: That's outstanding. Thank you.

Cheryl: Thank you.

Janis Ian: Thank you. I was just saying to somebody the other day who said, "Oh, my music, I'm never going to get anywhere with it. I'm just going to play these little places and make my little CDs." I said, "You never know where your work is going to end up or what it's going to do." Thank you for affirming that, Cheryl, that was great.

Alison Stewart: Cheryl. Thanks for calling in and sharing your experience. Let's go to line two, calling in from Atlanta, Georgia is Stahamili. Hi, Stahamili.

Stahamili: Yay. Yes, you said it right. Thank you, Alison.

[laughter]

It is such a joy to speak to you, Janis Ian. Three things. Number one, I love the new lyrics. I love that. The two lines you just quoted I'm right there with you. Secondly, I'm really looking forward to getting the album and listening to it. Third, I just wanted to say how much At Seventeen meant to me as a young Black girl growing up in Harlem. I think I was a little older than 17 when it came out but- [crosstalk]-

Janis Ian: I was too.

Stahamili: [laughs]- it felt like you were talking to me. That was my life.

Janis Ian: Thank you.

Stahamili: It helped me through so many moments to know that I wasn't just imagining stuff or just being weird.

Janis Ian: No.

Stahamili: The song is still in my rotation. I still have it in my iPhone right now.

Janis Ian: Stahamili, is that right? Am I saying it right?

Stahamili: You are. Yes, that's right.

Janis Ian: Oh my gosh, they send us to special schools for this. That's really great to hear. I am so proud of that song, and I find it so incredibly moving that it's still relevant to people. When you say that in a sense gave you courage and made you feel not crazy. I really thought when I wrote it that I was the only person on earth who felt like that. I honestly believe that. It's been such a wonderful journey to watch other people discover that they're not alone in that. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: Let's go to, I believe it is Bob calling in from Forest Hill, Queens on line five. Hey Bob, thanks for calling. You're on with Janis Ian.

Bob: Hey. Janis, you are one of my heroes in life. I'm a 61-year-old White male, and the first 10 years of my life were punctuated by air raid drills, race riots, the war in Vietnam, political assassinations, and the world didn't feel very safe. Your music among many other factors was an anthem to my two older sisters and myself. As I said to the screener that it made me feel a little safer in the world.

Like, "Okay, there are voices that are saying things that need to be said, and putting out a message there." I always considered-- My mother was a college librarian who had a career at a time when it wasn't fashionable for women to be in professions. I always considered her to be a feminist who walked her talk but didn't talk it, meaning that she didn't march in rallies or burn her bra, but if you treated her as less than, she didn't get mad. She just didn't understand, because in her mind, "Surely you couldn't mean that I was somehow less."

Janis Ian: [laughs] That's like Zora Neale Hurston who said that she knew that-- I can't remember the exact words, but she said something about she knew people were prejudice because of her color, and all she could think was, "How could you not want to know the fabulous me?" I always thought that was just a fantastic way to look at it. Thank you, Bob.

I think it's one of the great frustrations of these last two years for performers like myself who, when 9/11 happened, went on the road deliberately to try and make people feel safer and feel better about things. Who have gone on the road--

I was in Ireland during the troubles. I was in England during the riots. I was in LA during the riots. It's been very frustrating because we haven't been able to do what we are supposed to do as artists, which is get out there and give people hope and give them dreams. Thank you, Bob.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Janis Ian. Her new album is The Light At the End of the Line. We'll take a listen to the title track. We'll also play a little nugget we found from the WNYC archives from 1967, and we'll--

Janis Ian: I've been working with NYC forever. Oh my God. We'll be fine.

Alison Stewart: We'll take more of your calls after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart. We continue where we left off with Janis Ian about her final solo studio album, The Light at the End of the Line, which is nominated for a Grammy in the best folk album category. The Grammys are this Sunday. A reminder to listeners, Janis took calls as part of the interview, but this is an encore presentation, so no live calls today. I began this part of our conversation by asking Janis to tell us a little bit more about the title track of her now Grammy-nominated album.

Janis Ian: Oh my gosh, I sound like Pollyanna. It's a love song to my fans. Really. It's a farewell song. I used to joke with my tour manager that when I was ready to stop, we needed to do a tour and call it the End of the Line. Then I thought, [laughs] "It sounds like I'm dead." I thought the light at the end of the line, I really liked that. When I sat down to write it about half a verse in, I realized that I was really trying to say thank you to people who've stuck by me since I was 13/14 years old.

It's incredible. I grew up in this fishbowl, and they've been patient through all of my experiments and through all of my failures, and they've been cheering me on for the successes. Again, it's Pollyanna-ish, but they've been great to me. It's a love song to them.

Alison Stewart: Here's Light at the End of the Line.

[music]

It's the end of the line

and I know it's been rough

Oh, but time after time,

it was always enough

You were there when I laughed

You were there when I cried

You are there as I tell you "Goodbye"

It's the end of the line

and whatever they say,

I was yours, you were mine

Just a heartbeat away

Close enough to be kissed

Far enough to be missed

From the cradle to silver and grey

Alison Stewart: That's a title track from Janis Ian's album The Light at the End of the Line. Let's take another call since you said that song was for fans. We've got several on the line. Let's go to Nira, calling in from Berkeley Heights. Hi Nira, you're on with Janis Ian.

Janis Ian: Hi, Nira.

Nira: Hi, Janis. Such a joy to talk to you.

Janis Ian: My pleasure.

Nira: Hi, how are you?

Janis Ian: I'm good. So far- [crosstalk]

Nira: I was a young--

Janis Ian: -so good.

Nira: Wonderful. My favorite song was your Watercolor.

Janis Ian: I love that song.

Nira: Beautiful song. It helped me so much. I was a young woman in South India trying to make sense of my personal experiences and trying to find my stride in the world. I was opening to all of the different experiences other women had in the world. Your song helped me so much in figuring things out. It just suddenly dawned on me when I was a kid that they were universal experiences that all women had.

Janis Ian: What a great realization.

Nira: It was very powerful. You know,

"Go on, be a hero

Be a photograph

Make your own myths,

Christ, I hope they last

Longer than mine

Wider than the sky

We measure time by." Fantastic. It was just poetic.

Janis Ian: Thank you. I'm going to count on you if I forget the lyrics at some point.

Nira: [laughs]

Alison Stewart: Nira, thank you so much. Let's go to Robin, who's been holding on line nine calling in from a Long Island City. Hi Robin.

Janis Ian: Hi, Robin.

Robin: Hi. Janis, do you remember you took an acting class with Ron Burris and a bunch of us, I think it was in Hollywood.

Janis Ian: Sure, at the Stella Adler School, of course.

Robin: That's right. I was so impressed that you took an acting class when you were a singer, and I want you to know, if you haven't heard, Ron passed away just a few weeks ago. We were dear friends with him.

Janis Ian: I'm sorry to hear that.

Robin: I took his class. How did you hear about it? Why did you take acting class as a singer? Did it help you? Did you like Ron?

Janis Ian: [laughs] That's a lot of questions in one sentence. I loved Stella Adler. She was 50 years older than I was, and I went to her because an acting teacher named David Craig said to me, "Everyone must study with Stella Adler at least once." I was 33, Stella was 83, and we were fortunate enough to become friends to the day she died. Three days after she died, I got my last letter from her.

I didn't know Ron very well. I got to take his class because it was required, not that it wasn't worthy, but it was required of first-year students. I'm trying to remember the other questions. Yes, it helped me enormously because Stella Adler gave me a vocabulary for what I felt as an artist. She made me understand that as an artist, I could hold my head up because my lineage went back to the very first person who drew on a cave wall or who told a story around a fire. I was standing on the bones of 10,000 years and more. That was something to be proud of, and also a very grave responsibility. I am forever grateful to everyone at that school and at the current school in New York.

Alison Stewart: Let's take one more call. Tom, calling in from Burton, New Jersey. Hi, Tom.

Janis Ian: Burton, Tom.

Tom: Hello, good morning.

Janis Ian: Hey, good morning.

Tom: Lived in Teaneck at one time too, Janis. I think you did too also.

Janis Ian: I think I lived all over New Jersey, you name it, the FBI were chasing my folks, so we moved a lot.

Tom: Anyway, I have a story about Society's Child. I was in a large parochial Catholic co-ed high school in South Jersey where the teachers were predominantly nuns, and quite elderly. I was 13, freshman, English class. To my surprise, the teacher was a very young nun. The first day pulled out an old phonograph turntable and played Society's Child which was quite astounding to me compared to the other structure of the classes and certainly got everybody's attention and led to a fairly interesting discussion and a lot more attention in that class than many of the others. Every time I think of you or Society's Child, I think of that instance which is pretty cool. I thought.

Janis Ian: That's very cool, Tom. I have to say that Society's Child was circulating among the Catholic I don't know what you would call it, the various Catholic groups a lot. Thomas Merton mentions it in one of his books. Oddly enough, my closest friend or one of my closest friends is a medical mission sister, sister Miriam Teresa Winter, even now as we speak. I think that nuns did a great job in a sense subverting the hierarchy as it was. They went under the radar and they educated people about things not always, but sometimes that really we're not being talked about. I think they truly embraced-- I say this as a Jew, I think they truly embraced the spirit of Christ, of inclusiveness, of non-judgment, and of moving forward rather than status quo. Thank you for that story. That was great.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Janis, Ian, we're talking about her history. We're talking about her new album, The Light at the End of the Line, her last studio solo album. Since we're been talking, we've been going down memory lane a little bit, Janis. Our archivist, Andy Lancet, heard you were going to be on the show, went digging in the archives, and found this from one of the earliest parts of your career. This is from December 1967.

Janis Ian: Oh, my gosh.

Alison Stewart: Courtesy of WNYC folk music host David Seer is a little bit of an intro describing where you are in your career, and then a quick Q&A. Let's take a listen.

Dave Seer: Hi, this is Dave Seer. Back last May, Henrietta Chenko, and I brought you an interview with a virtually unknown young lady by the name of Janis Fink. We believe Janis to be an unusually gifted musician, songwriter, and commentator on our times.

We were pleased to bring you the interview then, and we're even more pleased to re-run that interview now, in the light of what has happened to Janis over the last seven months. Today, she is widely known for her singing and her songs as Janis Ian. Tomorrow night, Friday, December 8th, Janis will be making her debut at Philharmonic Hall in a solo concert that I guess will be virtually sold out.

Let's go back and listen to Janis Ian seven months ago when she was Janis Fink, and I think we'll not be too surprised to see where she is today.

I was standing on the corner, I was smoking on the sly

When along comes a grownup from the grown-up FBI

He said - this ain't Marlboro country, hon

Henrietta Chenko: Do you feel that you're a protest songwriter?

Janis Ian: It depends if the protest songs are just songs against Vietnam and Johnson. No, I write about what I feel.

Henrietta Chenko: Very often you're not really at one, let's say with the rest of the world.

Janis Ian: No, sometimes you're not very compatible. Most of the time we get along very well.

Alison Stewart: I loved that you know your mind even at that age.

Janis Ian: I'm so 15. Oh, my God. I changed my name partly because I didn't want my family to have a hassle and partly because the name Fink came from Ellis Island. It wasn't even the family name. I felt no attachment to it. It's always odd to me when people make a big fuss over it because it wasn't my name, to begin with. Oh, my gosh. I'm so glad that I was being polite because there were so many instances in those days when I was either intentionally or unintentionally fairly snotty. That was a great relief to hear that. Gee, oh gosh, I remember Henrietta and Dave. That was great. Thank you. That was just a nice slice for me.

Alison Stewart: I did want to ask you something. It's funny, we had you booked in the show and then something happened earlier in the week, and I thought, "I really want to ask Janis Ian about this." I don't know if you're aware of it, you might be, you probably are, that a well-known male singer-songwriter, claimed that Taylor Swift didn't--

Janis Ian: Doesn't write her own songs. There's tricks everywhere.

Alison Stewart: First of all, you are aware of it. I want to know your thoughts about that.

Janis Ian: I think that Taylor Swift is great, and I think she has done more for young female guitarists than any of the rest of us have done. I think that the way she's handled herself and her career are to be admired. There is a school of songwriting and I've done it myself, where you sit with a track or you sit with a group of musicians and you come up with a feel. Then from that feel comes the song.

I don't know if that's what he was talking about, but at the end of the day, it's still Taylor writing whatever the impetus is. If I'm listening to a drum track and I write a song around it, did the bass drum write the song? No, I wrote the song. He has since walked it back, and from what I read, said that he was quoted out of context. I've been dealing with the press since I was 14, so that's a long time.

The press company accepted that it does take things out of context for a headline. There are certain magazines and newspapers that thrive on that, but you have to have said it first. I don't have a lot of patience with that. Maybe I'm wrong, but I have to ask myself if someone would've said that about a male songwriter. You did hear in the early days, "Oh, Bob Dylan doesn't write any of his own songs. There's some mysterious person in Jackson or Astoria that writes them all." You did hear things like that mainly because it was such incredible writing.

I think if you look at Taylor's career and her boldness in being willing to step out and try different things, certain people who may not be as prolific would find it hard to believe that someone could be that prolific, but I believe it. I was in Nashville through her entire rise and I know how hard she worked.

Alison Stewart: Thank you for weighing in on that. We have got so many comments. I'm going to read a couple and then we're going to go out on, I think one of my favorite songs on the album. I just did Dealer's Choice. Let's See.

Janis Ian: Sure.

Alison Stewart: My introduction to Janis Ian came at 17 when I had just turned 17. I'd always been an outsider even to myself. The song is still in my heart. Thank you.

Janis Ian: Oh.

Alison Stewart: Someone described your music like a sonic stress ball for them.

Janis Ian: Whoa. The sonics. That's great.

Alison Stewart: Love that. So many great comments. I hope that after this segment's over you'll go check out our Twitter feed because there's a lot of love for you on there.

Janis Ian: Absolutely. Of course.

Alison Stewart: The song that I picked was Summer in New York. I just think it's just a great box.

Janis Ian: Oh, I love that song. Oh, that's Randy Leago again. We did the song and then when we were ready to finish the album I thought, "Man, this could really use just a George Gershwin clarinet moment." I called Randy and said, "That's what I need," and got the tape back the next day, or got the digital version back the next day. I love this song because summer is my favorite time to be in New York, just walking in the park and the congas and the chess players.

There's a great video of it that Carol Wecter did on YouTube where she shows the chess players and the conga players and all of that. You're dripping in New York in the summer, you're just absolutely dripping with sweat and yet there's something so vibrant about it. It's great.

Alison Stewart: The name of the album is The Light at the End of the Line. Janis, what a pleasure to have you. Thank you for taking listener calls.

Janis Ian: Oh, Alison, my pleasure. Really. Thank you all so much.

Alison Stewart: This is Summer in New York.

[music]

Jazz in Central Park

Chocolate kisses

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.