Jacqueline Woodson Celebrates Her Bushwick Upbringing

[MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Citysong]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. On the show today, Stewart Copeland of the Police will be here. He has a new book out called Stewart Copeland's Police Diaries, a cool memoir about the band before they hit it big. We'll also celebrate the Broadway show, Wicked at 20. Composer Stephen Schwartz will be with us as well as the current cast, the current Elphaba, and the current Glinda and we'll take your calls.

Plus artist Melissa Joseph, she's got this great small gallery show down in the Tribeca-ish area, and she works in felt, really interesting young artists that we'll introduce you to. That is all in the way, but let's get this hour started with a new book.

[music]

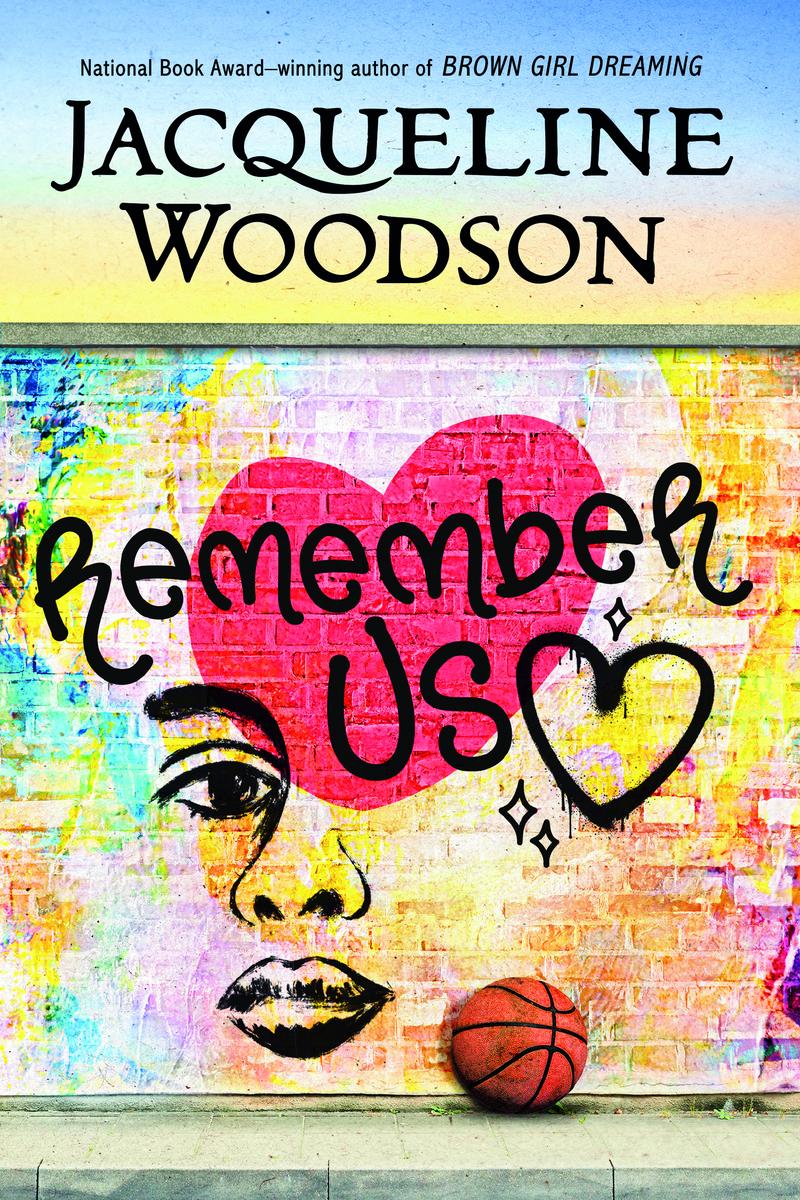

Alison Stewart: Author Jacqueline Woodson's latest middle-grade novel takes the reader to her old neighborhood, 1970s Bushwick. It's titled, Remember Us. The story follows a 12-year-old girl named Sage who is a basketball-loving kid who could smoke anyone on the court. However, Sage and her friends have more to worry about than just making it home before the streetlights come on. Fires have swept through the neighborhood destroying homes and causing families to move. Some left preemptively because you never know when the house might be next. The fires happen so often that the neighborhood became known in the media as the Matchbox.

Sage's father, a fireman, one of the few Black men in the department, died on the job. As Sage matures, she struggles with friendships, self-image, and the possibility that she too might have to leave her home. Remember Us is out now, and Jacqueline Woodson joins us to discuss. Jacqueline, welcome back.

Jacqueline Woodson: Thank you, Allison. Good to be here.

Alison Stewart: Really nice to see you. You told our friends over at Gothamist that writing about this area of Bushwick has been a goal of your entire career, that you really wanted to do this. Why was it so important to you?

Jacqueline Woodson: I think when I was living in Bushwick at the time, the fires didn't have a huge impact on me in terms of-- I was a kid, just being a kid. Looking back on it and watching how Bushwick has morphed into all of these other identities, I didn't want that part of it forgotten. Then I realized as I began thinking about it and eventually writing about it, how important it was, not only to my childhood but to the history of Bushwick as a neighborhood.

Alison Stewart: What was that community like when you were growing up there? How would you describe it?

Jacqueline Woodson: It was amazing. I just wrote a piece about my best friend Maria, who you meet in Brown Girl Dreaming and sharing food. Her mother would make Puerto Rican food. My mother would make soul food, and we would come out at night with our plates of dinners and trade them. That was pretty much the energy of the neighborhood. It was really people looking out for each other. It was a Black and Latinx community, and we were just a huge family of people surviving.

Alison Stewart: As you started to go back through your memory, what details did you wanted to include in the book Remember Us?

Jacqueline Woodson: I wanted to include Palmetto Street. That was first and foremost because I think that was the neighborhood that was the poorest at the time and where there were the most fires. I wanted to include stone buildings and talk about that history between wood-built structures and stone structures, and the history of the Vulcans, of Black firemen. I didn't know about that until I started writing the book. My niece Sadie, who's a librarian, helped me research it.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk about the research process. Where did you start?

Jacqueline Woodson: I started looking at the fires. I started looking at newspaper articles, going back to the Daily News, going back online and looking at the history of how Bushwick was talked about from the outside. People who didn't live there were talking about the neighborhood. As we know, when people from the outside talk about the place, it's a very different reality than the people inside talking about it.

Alison Stewart: When did you first learn that term, the Matchbox? That's how the media decided to portray the neighborhood.

Jacqueline Woodson: I've known that term since I was a child. I remember reading articles where they called Bushwick the Matchbox and thinking, "No, this is my neighborhood. This isn't a matchbox." It became this catchphrase in the media that didn't feel great, to say the least, to have a neighborhood talked about as this object that its time was coming, that eventually everything would burn.

Alison Stewart: My guest, Jacqueline Woodson, the name of the new novel is Remember Us. It centers around Sage who just loves basketball. She's really good at basketball. It's her thing. How does she fit in with the other kids in the neighborhood when we first meet her?

Jacqueline Woodson: When we first meet her, Sage, is at this crossroads where she's no longer this girly girl who likes to do, and I'm putting up quotation marks for that, do "girl things" like hopscotch and Double Dutch. She loves basketball, and she's at that point where people are telling her to make a choice. I really wanted to investigate the binary of the '70s. It wasn't like now where there was any fluidity, you had to make these choices in terms of an assumed gender. I really wanted Sage to go back and investigate that. I wanted that to be investigated in the book. I know Penguin says it's a middle-grade book, but it's actually breaking that rule because it's an adult looking back on that period.

As you know, middle grade is usually a person at that age talking about that age, but it's not that. Sage is looking back on that time where she loves ball, and I was very intentional about making her a very good ball player. As you said, she smokes the people on the court. She gets deep respect, she gets chosen for teams, and the girls are saying, "No, either you do that or you hang with us." She doesn't and she begins to question gender and all the rules around it.

Alison Stewart: I was going to say, I don't want to give much away, but there's this moment when Sage is confronted by this bully who really gets in her face about "acting like a boy". As you were thinking back and thinking about this period, why did people have such confining ideas about how boys act and how girls are supposed to act, and why would create such hostility because this bully is hostile?

Jacqueline Woodson: Yes. There was that hostility because I think there was a fear. I think people were fearful of their own genders and there wasn't a way to question it. There were no mirrors as Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop talks about. There was no way in which you could see reflections of yourself in the world and other people and for Sage and other girls for a long time. For this boy, if this girl is this really good ball player who is getting all this respect, what does that make him? I think a lot of times when there is fear, there is violence. Of course, in the book, I go to the emotional violence of that because I think that's important to talk about. The ways in which words can be very damaging and hurtful.

I wanted to put that moment in the book to show how fragile identity can be and especially when we're young people, how someone can say something that can break the spirit almost. The rebuilding of that spirit is part about growing up and realizing who you are and the strength of who you are.

Alison Stewart: How do you think about writing about some things that are tragic in here, this Sage loss of a parent, loss of a home, loss of the neighborhood, in a way that would be successful in touching 12 and 13-year-old readers, but also not frightening them?

Jacqueline Woodson: I think that part of it is about the language. You have to be very thoughtful about how you talk about stuff. In Remember Us, there is definitely a deep melancholy, but you also have a character who has survived. When that reader opens that book, the first thing they know is the person telling the story has lived to tell this story. That's really important. There has to be hope throughout the book so that the reader keeps turning pages. I think the reader is often reading the book from a very safe space. I think about myself as a young reader reading books like Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry where you're afraid of these things happening.

It's like, "I'm here, I have my popcorn, I have my book, I have my warm house, and I am okay so I can have this experience, and through this experience, learn empathy." That's what we gain by going inside these experiences of other people and seeing their lives and then closing the book and becoming a little bit different than we were when we first opened it.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is Remember Us, my guest is Jacqueline Woodson. There's some really cool history in the book. Sage's father was a member of the Vulcan Society and Organization of Black Firefighters. What was the purpose of the society? Tell us a little bit more about it.

Jacqueline Woodson: I think the first and foremost purpose of it was safety. I think when Black firefighters were first getting hired, there was a lot of racism. We don't see that many, but every time I see a Black firefighter now, I'm like, "Yo, there's the brother in the fire department." [laughter] Back in the day, there was a push to hire Black and Brown firemen, finally, but there was a resistance from white firemen and they didn't want to live in the firehouses with them because you have to sleep there. When fires happened, they pushed them to the front of the most dangerous fires.

In creating this fraternal order of Black firemen, it was a way of men coming together and having this safety net. There was actually a firehouse in Crown Heights, and I forget the number, I think it was 234, but it was all Black firemen. There was a way in which you go into these fires and it's like, "I know my brother's got my back. I feel safe in this space."

I think that's a lot of times why we create organizations like Black fraternities, sororities, Jack and Jill, for a safety net in a world where a lot of times people of color are not safe.

Alison Stewart: I think in the Vulcan Society, the president is a Black woman now.

Jacqueline Woodson: Oh, really?

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Jacqueline Woodson: That's amazing.

Alison Stewart: I think it's recent, actually, yes.

Jacqueline Woodson: That's amazing.

Alison Stewart: There's a great chapter. Do you mind if I read a little bit from your book?

Jacqueline Woodson: Oh, please.

Alison Stewart: It's really interesting because you go all the way back in the history of Bushwick. You write, "Before it was a neighborhood with wood-framed houses, bodegas, basketball courts, and double Dutch ropes spinning on every street, my neighborhood was a forest filled with trees. Before it was Bushwick, it was the land of the Lenape who lived among the trees and didn't need a bear coming on the TV screen on a Sunday night to remind them about the dangers of fire. They understood smoke and flame and the power of the woods.

When the Dutch explorers came, they called this place Boschwick, little town in the woods. Then they cut the trees down to make room for houses. The woods became the wood that became the wooden houses. Bluestone was laid over earth and ground to make sidewalks. Stoops leading to upper floors were slabbed. Windows and doorways were framed. Tar roofs were laid so that from above it must have looked like a long black street. The blocks that grew out of the woods were named for the trees that once thrived there, linden, cyprus, woodbine, evergreen, cornelia palmetto.

We lived in the shadow of the forest, the long-ago history of it mostly forgotten. Most of the blocks were treeless now, so we lived in the once was of the Lenape and the trees and our homes were burning. Who would remember this place? Who would remember us?" That's such a beautiful passage. There becomes this distinction between the wood houses and the brick houses. Could you explain that distinction?

Jacqueline Woodson: The brick houses were the safer houses. They didn't burn as fast. As a result, those houses became the more sought-after houses. Because they became the more sought-after houses, they became the more expensive houses. It created a class divide. That class divide was, of course, economic, but it was also a divide about safety, who was safer, which often a class divide is [chuckles].

Alison Stewart: Why do you think your character Sage turned out okay and survived? We know that from the beginning.

Jacqueline Woodson: I think she survived because of her own will, because of the friendship she had, because of the family she had. I think she survived because the way most kids survived, deep resilience. The hardest struggle is moving from childhood to adolescence. To survive that means to survive a lot of stuff.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: What do you hope people remember? I know that's a cheesy question because the name of the book is Remember Us. At the end, if there's something you hope people remember?

Jacqueline Woodson: I hope people always know that the space that they walked on has been walked on by people before them and to respect it as that. I always hate when I hear people say, "Oh--" I remember people saying, "I discovered this neighborhood called Bushwick." It's like, "No, you didn't. There were people before you there." Let's take it back to the Lanape, and let's always take our history back to the indigenous people wherever we are because they were here first and we're coming after them. Our deep responsibility is to remember history, especially in this moment where there's this attempted erasure of our histories, and to remember those walked on the land before us.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is Remember Us. My guest has been Jacqueline Woodson. Jacqueline, thank you so much for being with us.

Jacqueline Woodson: Thanks. So great to see you again, Alison. Take care.

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.