Isabel Allende's New Novel 'The Wind Knows My Name'

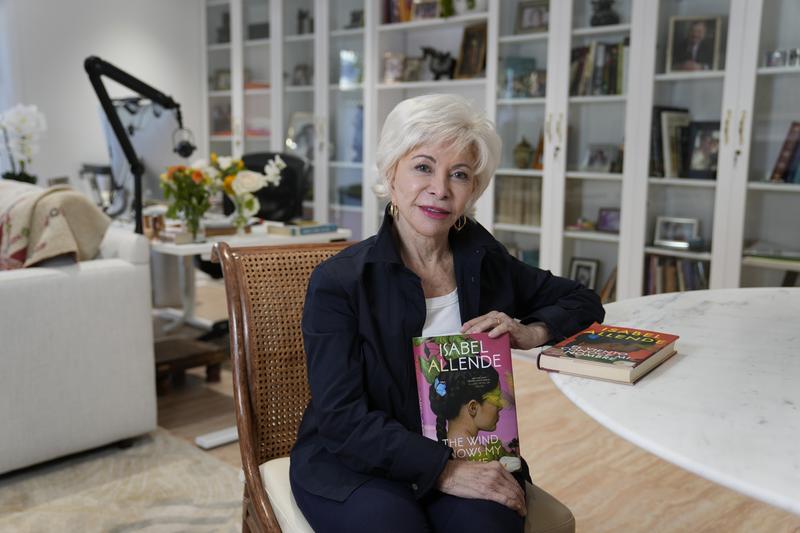

( (AP Photo/Eric Risberg) )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Thank you for spending part of your day with us, whether you're listening on the radio, live streaming, or On Demand, I'm really grateful you're here. On today's show, comedian Sarah Silverman has a podcast, a new comedy special out. She'll join us in about 30 minutes. Plus a new documentary premiering at Tribeca is about the history of Brooklyn Dance Hall. The directors will be with us and take your calls and your memories. We'll speak with writer Ruta Sepetys about how to mine your own life for inspiration if you dream of becoming a writer. That's the plan, so let's get this started with a celebrated writer whose new novel is both heartbreaking and heartwarming, Isabel Allende.

[music]

Isabel Allende's new novel intertwines the story of three people; Samuel, a boy orphaned by the Holocaust who we follow into adulthood, Leticia, a young woman who escapes a 1981 massacre in her village in El Salvador, she makes a life for herself in the States, and Anita, a seven-year-old girl nearly blind, separated from her mother at the US border and caught in bureaucratic limbo of detention centers and foster homes. Their lives collide, but not before they each endure emotional trials and trauma, as well as the kindness humans are capable of giving to one another. Part history lesson, part human rights alarm, The Wind Knows My Name was published yesterday and Isabel Allende whose work has been translated into 35 languages and who sold north of 70 million books, joins me now in studio. Isabel, welcome.

Isabel Allende: Thank you for having me, Alison.

Alison Stewart: As part of your practice, you begin writing a new work on January 8th of every year. When did you start this book?

Isabel Allende: I started last year, but I don't write a book every year. Sometimes a book takes more than a year, but I always wait until the next January 8th to begin something.

Alison Stewart: What do you remember writing on that day?

Isabel Allende: The day when I began this book?

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Isabel Allende: I remember the Kindertransport, which was the event that happened in 1938 when the Nazis were going to take over Germany, Austria, and Europe really. The Jewish families were already suffering the effect of this, and England offered 10,000 visas for children as refugees. The Jewish families had the horrible choice of either keeping the kids with the risk of ending up in a concentration camp or sending them away to an unknown destiny. My protagonist Samuel is one of those children.

Alison Stewart: I don't know if people know this. You probably know that Dr. Ruth was a child--

Isabel Allende: Yes, she was a survivor from the Kindertransport.

Alison Stewart: Yes, the book takes part-- The build-up to Kristallnacht, you describe how Samuel's family knew something was coming, but they weren't quite sure what it was, and how quickly things changed.

Isabel Allende: In 24 hours everything changed.

Alison Stewart: Gosh, what was it about the transport program that made you think, "I can make this into a novel?"

Isabel Allende: I didn't think that at the time. I started thinking about children being separated from their families in 2018 when there was a government policy that Trump established to separate children from their families to deter people from coming. Then I remembered the Kindertransport and other moments in history where children have been taken away from their parents. Well, in times of slavery, children will be sold, and nobody cared about what the parents felt or the child felt. Indigenous children that were taken away from their families to be put in some horrible Christian boarding schools to civilize them, and so many other instances. That event in 2018, and 19 was so horrible, and we saw the pictures and the photographs and the videos of the children in cages, of mothers screaming, of the Border Patrol, which I'm sure were as devastated as everybody else, pulling the babies out of their mother's arms. It's something that I needed to write about.

Alison Stewart: All three of your characters, and we'll talk about them each individually, leave their homes under these horrible circumstances. It's an experience you know. You were a political refugee in Venezuela for 13 years after the Chilean government was overthrown in a coup, a government run by a relative of yours, Salvador Allende. What do you understand about that experience that you wanted to make sure was communicated in this novel?

Isabel Allende: Well, the novel is about the tragedy of displacement. It's very different to be a refugee, someone who seeks asylum from being a migrant. Usually, an immigrant is a young person who chooses to go to another place in search of a better life. A refugee is someone who's running away from something. Usually doesn't have a choice, where he or she goes, is received with hostility, and is always looking back, waiting for the moment when they can return to where they left behind. I have had both experiences, being a refugee and being an immigrant. I can tell you how different it is. An immigrant looks to the future. A refugee is always stuck in the past. This book is, of course, about that, but this book is mostly about the thousands and thousands of people who are trying to help.

We hear only about the tragedy, we hear about the horrible things that happen and the horrible things that people do to each other, but we don't hear about the people who do good. Well, in the case of the refugee crisis, most of the people who are working to alleviate it are women because there is no glory or fame, or money in this work. It's just compassion and heart, so women do it. That's what I'm interested in, those people.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Isabel Allende, the name of the novel is The Wind Knows My Name. Let's learn about our three protagonists. Samuel, this boy who is orphaned by the Holocaust, he's sent on the Kindertransport, his mother makes this really difficult decision. From your research around the Kindertransport, and around Kristallnacht in this time, what was a detail that made it into the novel, and that really helped shape this portion of the novel when we first get to know young Samuel?

Isabel Allende: To me, it's imagining the family, imagining one story, one person with a face, with a name. In this case, someone is a musical prodigy. If he would have had a normal life, he would have been an extraordinary composer or performer, but because his life is cut when he's almost six, he's cut away from everything, including music. He never develops fully all his talent. I tried to imagine his life. There's a moment in the novel when he goes to the Holocaust Museum. He's already an adult, and he's looking among the-- I have been there many times, and he's looking for his past. He's looking for his family. Will he find his mom? Will he find his father among the thousands of pictures and names? Just imagining that was very hard.

Alison Stewart: The person, as a young man who shows him kindness is a former military officer who thinks of him as a grandson and gives him a medal and tells him, "This medal will help you be brave."

Isabel Allende: Yes, it's an old Prussian Colonel that did the First World War and he sees the coming of the Nazis as something horrendous that is going to happen. He can imagine the horror. He helps this Jewish family and falls in love with a kid. The Colonel would sit in the hall of the building where they lived to listen to the kid playing. When the Kristallnacht happens, and these mobs come to destroy and kill and beat up these families, he shelters them. This Colonel gives him his medal that he won in the war, and he gives it to the kid and says, "This will give you courage. If you ask the medal to help you, it will always give you courage." The kid has the medal forever until 80 years later, he can give the medal to another child who is going through something similar to what he endured.

Alison Stewart: Let's bring Leticia into the conversation. She escapes the massacre of her village by fate. She happens to have been in the hospital and then when her father returns home, realizes what has happened and is not really able to speak of it for a long time. The massacre happened in El Salvador in 1981. The town was El Mozote. You write about this in a very straightforward and graphic way. Why did you decide to be so graphic in some of the details?

Isabel Allende: Because people cannot understand why people leave their places of origin. Why do we have today millions of Ukrainian refugees that we didn't have a year or so ago? Because something has happened in their country that forces people out. In the case of Leticia, she was a child with her family in a small village in El Mozote. There were several villages there and the military, which by the way had been trained by the CIA, goes to El Mozote to terrorize the population with the idea of stopping the population from helping the guerrillas, which is a fantasy because it's not happening in reality. There are no guerrillas there. They're just farmers and poor people who live off the land. They go there and they kill more than 800 people in the most horrible way. They burn people alive, they chop them in pieces with machetes, they kill all the children.

With the blood of the children, they write graffiti on the walls with total impunity protected by the government, protected by the military and there's no accountability for this.

Alison Stewart: It's all right if I read a bit from here. There were no guerrillas in El Mozoteinic farm workers from the village and surrounding areas who flocked there in search of safety when the soldiers flooded in. But there was no safety to be had. That day, December 10th, the soldiers of the battalion arrived in the remote region by helicopter and occupied several villages in a matter of minutes. The objective was to terrorize the rural population to keep the people from supporting the insurgents. The following morning, the soldiers began separating the men to one side of the village and the women to the other. The children were sent to the rectory, which they called the convent. They tortured everyone including the children, trying to glean any information. They raped the women and murdered every living soul. Some were shot, others were stabbed with knives or machetes, some were burned alive.

The children were run through with bayonets and slaughtered with machine guns and then the convent was burned to the ground. The little charred bodies trapped inside were unrecognizable. With the blood of a murdered child, they wrote a message on the wall of the school, "One dead child, one less guerrilla." They also killed the animals and set fire to the houses and fields, then they left leaving only blazing coals and bodies strewn across the ground. They fulfilled their mission of scaring the locals into submission by annihilating more than 800 people, half of them children with the average age of six. Leticia has nowhere to go. Her father comes back, he's dazed, he's traumatized. What does she hope for her life after this?

Isabel Allende: She hopes to make a life somewhere else, but she carries the loss. The father doesn't even speak anymore. He barely survives because he needs to help Leticia. He has to care for his only remaining child. He tries to make a life in the United States as an immigrant, and it's very hard. He has minimal work. He doesn't speak English. He doesn't have legal documents. It's very hard for him. Leticia is the second generation. She makes it in the States. She works as a nanny and as a housekeeper. Samuel by now is 86, and he has Leticia as a housekeeper when the pandemic hits. Samuel asks Leticia to come and live with him because he doesn't want to be alone. Now we see their relationship.

Alison Stewart: We're discussing the novel, The Wind Knows My Name. It's by Isabelle Allende, who is our guest in studio. We bring in Anita, a nearly blind, very smart seven-year-old girl, separated from her mother in 2019 at the border, as part of the Trump administration's policy where every migrant, including asylum seekers attempting to cross the border, were detained and criminally prosecuted. What went into your decision to have Anita have near blindness?

Isabel Allende: Because it's a case that I saw through my foundation. I have a foundation, and we work with organizations and programs at the border. One of the cases was a little girl called Juliana that came with her mother and a little brother called Juan and they were separated at the border. The girl was blind. They were separated for more than eight months that they couldn't find the mother in the bureaucracy. When finally they were reunited, they were all deported.

Alison Stewart: I want to ask about your foundation. I was going to wait and ask about it, but I think this is a good time to talk about it. Your foundation works in spaces to protect women, supporting organizations like Mujeres Unidas y Activas. I was really moved by a piece that was on their website by a 16-year-old girl with the title, "With Biden's Asylum Ban I wouldn't be here." What kinds of programs do you want your foundation to invest in and support?

Isabel Allende: We help organizations that are already working in the field. We don't invent anything. We don't have the infrastructure for that. Through these organizations, we get to see the people who are helping and the way to help-- for example, there's an organization, excuse me, called KIND: Kids In Need of Defense. 40,000 lawyers that are helping these kids. We work also on the other side of the border in the refugee camps, I don't know, installing latrines, where women can go without being raped on the way. We try to find ways of informing people of their legal rights, of how they can navigate the system, which is very complicated. Right now, with th new ban, the Biden bans, for example, an asylum seeker needs to use an app in the phone.

Not everybody has a phone. Not everybody knows the technology to use it. Then it doesn't work everywhere. It only works in northern Mexico and Mexico City. Someone coming from Haiti or Venezuela has no way of getting it. If you are coming through another country and you have not seeked asylum in that country and be denied, you cannot seek asylum in the United States. Which means that if you are passing through Mexico or through El Salvador or whatever other country, you have to wait maybe years to be denied asylum. It's impossible.

Alison Stewart: You have a few characters in the book who raise questions, or who are just completely ignorant. One character is completely ignorant about what's going on. He only hears it as background in the news. Neither of them are bad people. They're not evil people. Why was that important to you and how did you balance creating these characters who were multi-dimensional, not just mustache-twirling bad guys?

[laughs]

Alison Stewart: Who were ignorant or had some feelings that might not be the ones that you share?

Isabel Allende: Because most people are like that. We are overwhelmed with news and information. We cannot process everything. Unless we know one case and we know one story, we can't connect to the tragedy that's going on, or we can't connect to the war or to famine or to anything because it's too much. I totally understand that, because I feel that way about many issues. I am very concerned about everything that happens to women, but I'm not concerned, for example, about things that happen to other people who are not within the little niche that I work with. I understand that, and that's the way the world works. It is in the book, of course. Also, there's a point in the book when Samuel, he's sheltered in place because of the pandemic alone with Leticia. For the first time in his life, he has time to reflect upon his life, upon the fact that he has had a sheltered life. That he has had a protected life. That the trauma of the separation is like a hole in his heart. He has protected himself from suffering and from knowing. He says, "My sin is the sin of indifference. Sooner or later you pay for that." He has the good chance of atoning for that sin when Anita appears in his life.

Alison Stewart: These three protagonists, they intersect at some point. When you're working on a piece like this, do you work in a linear fashion? Do you write by timeline or do you know, "I know these people are going to intersect, and now I'll work backwards."

Isabel Allende: I don't know anything, Alison. I have no idea. I just start a book and things happen. Sometimes I find myself in a dead alley that I can't get out and say, "How did I get here?" Then I have to go in another direction. I know writers that have a script that have everything written before. That they have a map. I can't work like that. For me, everything happens in the womb. It's organic. The characters start to grow and do things that are unexpected.

Alison Stewart: I love you threw your hands up in the air for this radio, "I don't know where they come from."

Isabel Allende: I have no idea what's going to happen.

Alison Stewart: Of your three protagonists, whose voice came to you first?

Isabel Allende: Anita.

Alison Stewart: The little girl.

Isabel Allende: The little girl. I could have been that girl. My child could have been that girl. Yes, Anita, for sure.

Alison Stewart: Whose voice took the most time to refine?

Isabel Allende: I had very good help with Leticia because one of my best friends, a person that I see every day for a cup of coffee is from El Salvador. She did not escape from El Mozote, but she escaped from similar circumstances and came to the United States escaping from the brutality of the military, and the gangs in El Salvador. She was my source of information, my research ally. That voice was easy for me because it was just a matter of listening to her. Samuel was more difficult because he's an 86-year-old Jewish man from Austria. I couldn't be more far removed from him.

Alison Stewart: My guess is Isabel Allende. The name of the novel is The Wind Knows My Name. One of the themes that runs through the book is, though these people and you touched on this earlier, experience such difficulty, there are these acts of kindness, people who go out of their way to help them. We mentioned the military gentleman. There are people who have pro bono lawyers who are involved. People who give people jobs and say "Okay, show up, and I'll try to help you out." As you were writing this book, how did you balance the truth of the horror and the difficulty with the moments of hope?

Isabel Allende: That was easy, because I see the hope, and I see the help all the time. I work with that. Selena, for example, was based on two women. There are social workers and they are friends. They even look like her.

Alison Stewart: She's trying to help find his mother and trying to find their home.

Isabel Allende: They represented Anita. It's easy because I see them all the time. Through the foundation, we are permanently in touch. We get the updates of what's going on. What does it mean when Title 42 is eliminated and is replaced by two bans that are just as hard? What does it mean exactly? I'm informed about all that.

Alison Stewart: How do you name your characters, Isabel?

Isabel Allende: When I wrote The House of the Spirits, among the many theses that were written about the book, one of the thesis was about the names in the book, and I didn't know but every name means something that has to do with a character. Then I realized that names mean something. I bought a book, a dictionary of names. For a long time, I would name my characters according to the dictionary. I thought, "Well, if this character is just a jerk, let's find a name that represents the jerk." Well, now I don't do that. This time I chose names from the people that I know. Letecia and Selena, they are names from the community of people that I know that are helping. Samuel, I made it up.

Alison Stewart: At this point in your career, Isabel, what inspires you to keep writing?

Isabel Allende: I love the process. People say, "Well, you are 80, why don't you retire?" I'm retired of everything I don't like, of toxic people, of cocktail parties, of signing books, of book tours. I'm retired of all of that. I am totally involved with the writing that I love, with my dogs, and my husband.

Alison Stewart: That is inspirational and aspirational. The name of the novel is The Wind Knows My Name, it's been by my guest Isabel Allende. Isabel, thank you for coming to the studio.

Isabel Allende: Thank you, Alison.

Alison Stewart: Sarah Silverman is up next.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.