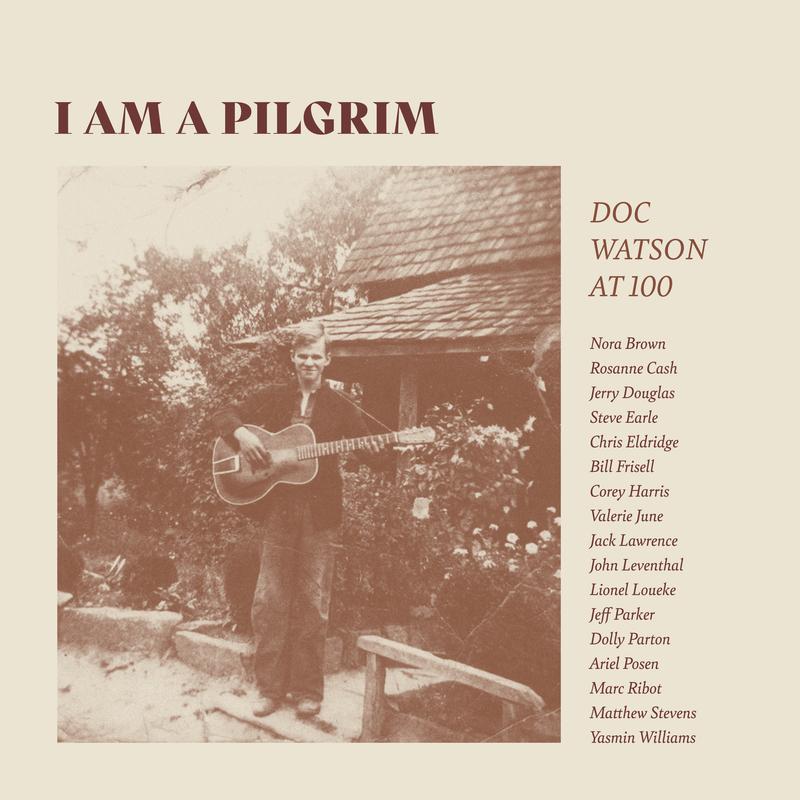

'I Am A Pilgrim: Doc Watson at 100.'

( Courtesy of FLi Records/Budde Music )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All of It. I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Thanks for spending part of your day with me. Next week, spend some time with us as well. We have great conversations coming your way. We're going to speak with the director of Reggie, the new documentary about baseball legend Reggie Jackson. We'll also talk about the new film adaptation of Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret. Plus W. Kamau Bell will join us to discuss growing up mixed race. He has a new documentary out about it. We'll talk about Cellino & Barnes the comedy musical. That is the play. That is the plan. Right now let's get this hour started with Doc Watson at 100.

[MUSIC - Doc Watson: Deep River Blues]

Let it rain, let it pour,

Let it rain a whole lot more,

'Cause I got them deep river blues.

Let the rain drive right on,

Let the waves sweep along,

'Cause I got them deep river blues.

My old gal's a good old pal,

And she looks like a waterfowl,

When I get them deep river blues.

Ain't no one to cry for me,

And the fish all go out on a spree,

When I get them deep river blues.

Alison: A new album out today celebrates the legendary guitarist Doc Watson, 100 years after his birth. Born March 3rd, 1923, the blind North Carolina guitarist came to prominence during the folk revival of the 1960s. Thanks in part to a landmark concert at PS41 in Greenwich Village. Following his death in 2012, the folklorist Ralph Rinzler said of Watson, "He's single-handedly responsible for the extraordinary increase in acoustic flatpicking and fingerpicking guitar performance." Now a group of musicians who are influenced by Watson have come together for the new album I Am A Pilgrim: Doc Watson at 100, featuring mostly guitarists and vocalists. The tribute group includes Steve Earle, Rosanne Cash, Valerie June, Bill Frisell, and none other than Dolly Parton.

[MUSIC - Dolly Parton: The Last Thing on My Mind]

It's a lesson too late for the learning

Made of sand, made of sand

In the wink of an eye my soul is turnin'

In your hand, in your hand

Are you going away with no word of farewell

Will there be not a trace left behind

Alison: To talk about the album Watson's legacy I'm joined by three guitarists who come from different stylistic backgrounds. The album's producer is local musician Matthew Stevens, a guitarist who has worked and taught extensively in jazz. Matthew, welcome.

Matthew Stevens: Thank you so much. So happy to be here.

Alison: Guitarist and singer Chris Eldridge has played as a member of the Bluegrass bands such as the punch brothers and most recently Mighty Poplar. He was also once part of the public radio family as a member of the house band on live from here. Hi, Chris.

Chris Eldridge: Hi, there. How's it going?

Alison: It's going well, thank you for asking. Corey Harris is a 2007 MacArthur Fellow and blues guitarist and singer based in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is also the author of a recent book called Blues People Illustrated: Legends of the Blues. Nice to meet you, Corey.

Corey Harris: Greetings.

Alison: Matthew, where did the idea for the tribute album come from?

Matthew Stevens: It came from Mitch and Matt Greenhill, Mitch managed Doc for a long time after his father had begun initially managing Doc in the 60s, Manny Greenhill. Mitch and Matt work with a publisher named Peer Steinwald, with a company called Budde in Germany and they have been working together for multi-generations actually, the two respective companies Folklore and Budde on the publishing side of Doc's music and to celebrate his centennial, they wanted to come together and do a tribute record. That's where the idea initially came from.

Alison: Matthew, how did the selection process work for contributors that you wanted to have be a part of this?

Matthew Stevens: I think that we were eager to showcase the enormous breadth of musicians that Doc and his music had influenced and how it was able to be interpreted and reimagined in so many different ways by artists from all these different corners of music and really point to the long-lasting impact and longevity of Doc's legacy and the music that he represents.

Alison: Corey, why did you want to get involved with this? Why was this a project you wanted to take on?

Corey Harris: I've long admired Doc Watson for his musicianship and then being a long-time resident of Virginia, the sound that he had was very much of a Piedmont mountain sound so it's something that I can relate to. Even though I didn't really grow up around bluegrass I can hear the blues in it.

Alison: Chris, how about for you? Why was this a project that interested you?

Chris Eldridge: For me as a musician, being a bluegrass musician essentially and a flat picker it's the guitar style that Doc really made famous where you can play fiddle tunes usually at breakneck paces with a flat pick. Doc he's just one of the key figures who got it all going. Without Doc, you don't have a lot of the evolution of the music, especially from the guitar player perspective, especially from the perspective of a guitar player playing lead in this kind of music. Doc is just this monumental figure and to join with all these other amazing heroes to celebrate Doc is like, what an opportunity.

Alison: Chris, what is this flat picking you speak of for people who don't speak guitar?

Chris Eldridge: Flat picking it's a style. Basically, it was born where guitar players used to play old-time music, fiddle music, music that was social back in the day. Where you might have a group of people hanging out, dancing. You'd have a fiddle player playing melodies [flatpicking sound]. This music that's really syncopated has a real kind of groove and you can get a bunch of people moving to it. The guitar player, if there was a guitar player would just be playing very simple rhythm guitar.

What Doc did is he took those melodies that the fiddle players would play on their instruments and he just brought that to the guitar so that you can have these rapid-fire melodies coming out of a guitar. It's a very fast style. You're just using the flat pick going back and forth, as opposed to people who use all of their fingers or several of their fingers on their right hand to make the sound. Doc is just kind of [fingerpicking sound]. It's a very exciting sound.

Alison: Let's take a listen. We have a little bit of Doc Watson flatpicking.

[MUSIC- Doc Watson flatpicking sound]

That did sound like just what you said, Chris.

[laughter]

Corey, I have also queued up some of Doc Watson's fingerpicking. What's unique about it or what's special about his version of fingerpicking?

Corey Harris: What stands out to me with his fingerpicking is how advanced it is. His fingerpicking and his flatpicking were at a very high level. From listening to his fingerpicking you can really hear that he spent a lot of time with not only people in his community but people from different communities like Black folks. I know western North Carolina have even Native American people so you can really hear the pastiche in his playing.

Alison: Let's listen. This is Doc Watson's fingerpicking.

[MUSIC- Doc Watson fingerpicking sound]

We're talking about the album I Am A Pilgrim: Doc Watson at 100. My guests are producer and guitarist Matthew Stevens, as well as guitarist Chris Eldridge and Corey Harris who are part of the project. Matt, I think it's interesting that Doc Watson is often thought of, as people think acoustic music right away picking styles right away. He also played electric guitar, correct?

Matthew Stevens: He did. He was playing a Gold Top Les Paul in the 40s and into the 50s in local dance bands around Tennessee, playing pop standards at the time. It wasn't until as you mentioned in the introduction, Ralph Rinzler came down and said, "Hey, there's this big folk revival going on, you got to come up here and start playing all these old tunes that you learned as a kid for some bigger audiences," which is when he switched from electric to acoustic guitar. I think that the story goes that he initially showed up to a session. Chris would be able to enlighten us on this.

He showed up to a session maybe with Gaither Carlton, somebody, and he had his electric guitar. It was a session that Ralph was producing and he said, "Forget about it. Don't even bother to play." It wasn't until Ralph heard him playing banjo that he said, "Gosh, this guy's an incredible talent and I really need to focus on getting him some exposure and convinced him to switch back to exclusively acoustic guitar." I'm not sure how much convincing it took but that was the story.

Alison: Chris, do you want to add anything to the story?

Chris Eldridge: I think that's pretty good. I think you pretty much hit it. Yes.

Alison: Matthew, so not only did you produce the album, you play a song on it with Jeff Parker, a guitarist. It's called Alberta from Watson's '66 album Southbound. Let's listen to a little bit of the original.

[MUSIC - Doc Watson: Alberta]

Alberta let your hair hang low

I saw her first on an April morn'

As she walked through the mist in a field of hay

Her hair lit the world with its golden glow

And the smile on her face burned my heart away

Alison: Matthew, tell me a little bit about this song and where it fits in Doc Watson's career.

Matthew Stevens: Yes. I think it's a beautiful song and it's a little bit unusual from what I had heard in terms of the amount of core changes in harmony that's happening in the song. I think that that's part of the reason that I was drawn to it to play with Jeff because neither of us sings as beautifully as Chris or Corey do, and so we were going to do an instrumental version of something.

There's a lot of harmony that moves through that song and adds a lot of interest to it. There's a lot to sink your teeth into as an instrumentalist and neither Jeff or I can lay any claim to being bluegrass guitar players or flat pickers in the lineage of Doc. It just felt like a really great vehicle for us to find our way into and do what we do. I think that in terms of where it fits into Doc's discography, it's a traditional song and I think it just sits within that realm of the music that he played.

Alison: Let's hear the version that is on the album, I Am A Pilgrim: Doc Watson at 100.

[MUSIC - Jeff Parker and Matthew Stevens: Alberta]

Alison: We're discussing the album, I Am A Pilgrim: Doc Watson at 100 with Matthew Stevens, who you heard there. He's producing the album as well as guitars and singers, Chris Eldridge and Corey Harris. We'll hear Chris and Corey's contributions to the album after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. We're discussing an album that comes out today called I Am A Pilgrim: Doc Watson at 100. My guests are Matthew Stevens, producer on the album, as well as Chris Eldridge, guitarist and singer, and Corey Harris, guitarist and singer, who also appears on the album. Corey, you're up. You're MacArthur Fellowship was awarded for, here's the quote, "Leading a revival of Mississippi Delta blues by infusing traditional styles with influences from jazz, reggae, gospel, and African and Caribbean folk styles." You wrote a book about blues legends. First of all, why did you focus on the blues? What led you to the blues?

Corey Harris: My family comes from the south, from Northeast Texas, Louisiana, near Texarkana, and so it was just something that was in the family heritage that I grew up listening to.

Alison: When you think about Doc Watson, how does he connect to those influences or how did you make the connection?

Corey Harris: For me, the connection was made just through being a guitarist and loving to hear great guitarists. Later on, I moved to the Piedmont region of Virginia and I had a chance to go to MerleFest while Doc was still alive and I had a chance to meet him briefly. It was just a great experience to actually be able to put an image to the music that I was hearing all those years.

Alison: The song you play on the album is How Long Blues. Did you choose that one?

Corey Harris: I did, yes.

Alison: Tell us why. Tell me about it.

Corey Harris: That's a Leroy Carr tunes. Leroy Carr, the great piano player, wrote a lot of hits in the 1930s. With Doc Watson playing this song, he's really showing a deep awareness of what was hit blues music back in the early days.

Alison: Let's hear a little bit of Doc Watson's version and then we'll hear yours. This is How Long Blues.

[MUSIC - Doc Watson: How Long Blues]

How long,

How long,

Must I keep my, all-watch in pawn?

How long,

How long,

Honey tell me how long?

Alison: All right. We're about to hear your version of it. What was the vibe you wanted to put out with your version?

Corey Harris: I wanted to give the sense of longing, waiting. I don't know if waiting in vain is the correct phrase but a sense of longing and a sense of lost love.

Alison: Let's hear How Long Blues from Corey Harris.

[MUSIC - Corey Harris: How Long Blues]

How long,

How long,

Has that evening train been gone?

How long,

How long,

Baby how long?

As at the station, when my baby leaving town

Was disgusted, no way could peace be found

For how long,

How long,

Baby how long?

Hear the whistle blowing, cannot see my train,

Deep down in my heart baby, there's an aching pain.

How long,

How long,

Baby how long?

Can I play?

Alison: That's Corey Harris's How Long Blues. Couldn't interrupt the guitar solo there. Chris, you're up. [laughs] You had mentioned you've worked in bluegrass and folk music, but if you dig down into your bio, it says that your first love was electric guitar.

Chris Eldridge: Yes, it was. I started playing electric guitar-- I have a weird history because my parents are both bluegrass musicians. They're both banjo players, in fact, which is miraculous that I was born with 10 fingers and no webbing. I grew up very much in that music but I think it's because my parents did that, I wanted to be involved in music but not in the way that they were doing it. I got into electric guitar players I got into the Allman Brothers. I loved Stevie Ray Vaughan. I got into more jazzy fusion kind of stuff.

When I was a little older, when I was about 14, my mom gave me a record by the great bluegrass guitarist, Tony Rice, who was actually a family friend. My father played in a bluegrass band called The Seldom Scene. We were very much kind of in and amongst the musicians. That brought me back into the fold of acoustic music. From there I just dove deeply and realized there was an osmosis thing that had been happening all along. Felt like home.

Alison: All right. We're going to hear a little bit of Little Sadie, which was recorded by Doc and says [unintelligible 00:20:39] '65. Let's listen to their version.

[MUSIC - Doc Watson: Little Sadie]

Went out one night for to make a little round,

I met little Sadie and I shot her down.

Went back home and I got in my bed,

44 pistol under my head.

Wake up next morning 'bout a half past nine,

The hacks and the buggies all standing in line.

Gents and the gamblers standing all around.

Alison: All right. Chris, what made you pick this song for Doc Watson at 100?

Chris Eldridge: I've always loved the song. Obviously, it's a dark song. The first line is I went out one night to make a little round. Met little Sadie and I shot her down. There's a real darkness to that. The guy gets what's coming to him in the end. He goes to jail, they catch him. That was something I kind of wrestled with, like, do I actually want to do this song that has this violence baked into it? We have enough of that coming at us all the time these days. Ultimately, I feel like that's part of the tradition. A lot of old traditional music, they just talked about bad folks and bad things that happened, and songs helped you contextualize that stuff. Also just I've always loved the music itself. You can strip the words away. I've always loved the music of that song.

Alison: Well, let's take a listen. This is Chris Eldridge with Little Sadie.

[MUSIC - Chris Eldridge: Little Sadie]

Went out one night for to make a little round,

And I met a little Sadie and I blowed her down.

I went back home and I got in the bed,

44 pistol under my head.

I woke up the next morning about half past nine,

And the hacks and the buggies are all standing in line.

The gents and the gamblers are standing around.

Carried little Sadie to her burying ground.

Then I begin to think about a deed I'd done

So I grabbed my hat and away I run

I made a good run but a little too slow.

And they overtook me in Jericho.

I was standing on the corner, reading the bill,

When up stepped the sheriff from Thomasville,

He says, "Young man, ain't your name Brown?"

Alison: That's Chris Eldridge from, I Am a Pilgrim: Doc Watson at 100. That album Drops today. It's honoring the legendary guitarist, Doc Watson. My guests are Corey Harris and Chris Eldridge, both musicians who appear on the album as well as Matthew Stevens, a producer guitarist who's on the album as well. Matthew, so you come from the jazz background. Your website describes you as a professor of jazz studies at Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. You've listed works with Esperanza Spalding, Terri Lyne Carrington, Dave Douglas, all jazz musicians. What does an album of mostly folk music like this demand from you, a producer that's different from your experiences producing jazz?

Matthew Stevens: Fundamentally, I think I approached it the same way. I think maybe something that gave me a bit of an advantage is that because I don't identify as an old-time or bluegrass musician, I wasn't afraid of breaking any rules potentially, because frankly, I'm unaware of them. [laughs] I felt like I could ask anybody that I liked and that I thought would do an interesting version of some of this music to contribute. That was exciting and I really have to give a shout-out to Mitch and Matt Greenhill and Peer for giving me that amount of creative license to just ask not only people like Corey and Chris, but Yasmin Williams and [unintelligible 00:25:21] and Valerie June and Marc Ribot, and people from all different corners of music. I think that really gave me a bit of an advantage to not worry about [laughs] upsetting the bluegrass folk. [laughs]

Alison: Before we wrap this up, Corey, is there anything you want people to think or reflect on about Doc Watson when they go and they stream this or buy this record?

Corey Harris: I think that Doc Watson represents a challenge to the popular idea of genre in America. Because he really transcends so much of what we've now walled off in music. He transcends that. I think that's what people will hear.

Alison: Chris, how about for you? What would you like people to think about and remember?

Chris Eldridge: Well, I think what made Doc so special, he was an innovator in all these ways. Also if you just take his own music on its own terms, what stands out to me is that it's so honest. That's the through line that ties everything that he did together. You just, you hear the person behind the music. I think that's part of why he was so powerful because his humanity was super on display and that's something we can all connect to as fellow humans. I just think, yes, kind of what Corey was saying, there's something just universal about the music and the way that people can receive it. Doc Watson's is just the greatest. There you go.

Alison: Out today I am a Pilgrim: Doc Watson at 100. My guests have been Corey Harris, Chris Eldridge, and Matthew Stevens. Thank you so much for being with us today.

Chris Eldridge: Thanks so much, Alison.

Corey Harris: Thank you. Thanks, Alison.

Matthew Stevens: Thank you. Thank you, everyone.

Alison: I want to let you know that Matthew and some of his collaborators on the album stopped by our studios yesterday for a session with Soundcheck. That podcast will be available next Thursday, May 4th, but the folks at Soundcheck were kind enough to let us play a little bit today. So we thought we'd go out on a cut. Here is singer-songwriter Valerie June and Matthew Stevens with a cover of Handsome Molly.

[MUSIC - Valerie June and Matthew Stevens: Handsome Molly]

Well, I wish I was in London,

Or some other seaport town,

Where I'd put my foot on a steamboat,

And sail the ocean 'round.

While sailing 'round the ocean,

While sailing 'round the sea,

Where I'd think of handsome Molly,

Wherever she might be.

Don't you remember, Molly

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.