How the Black Panther Party Branded Itself

( Courtesy of Poster House )

[music]

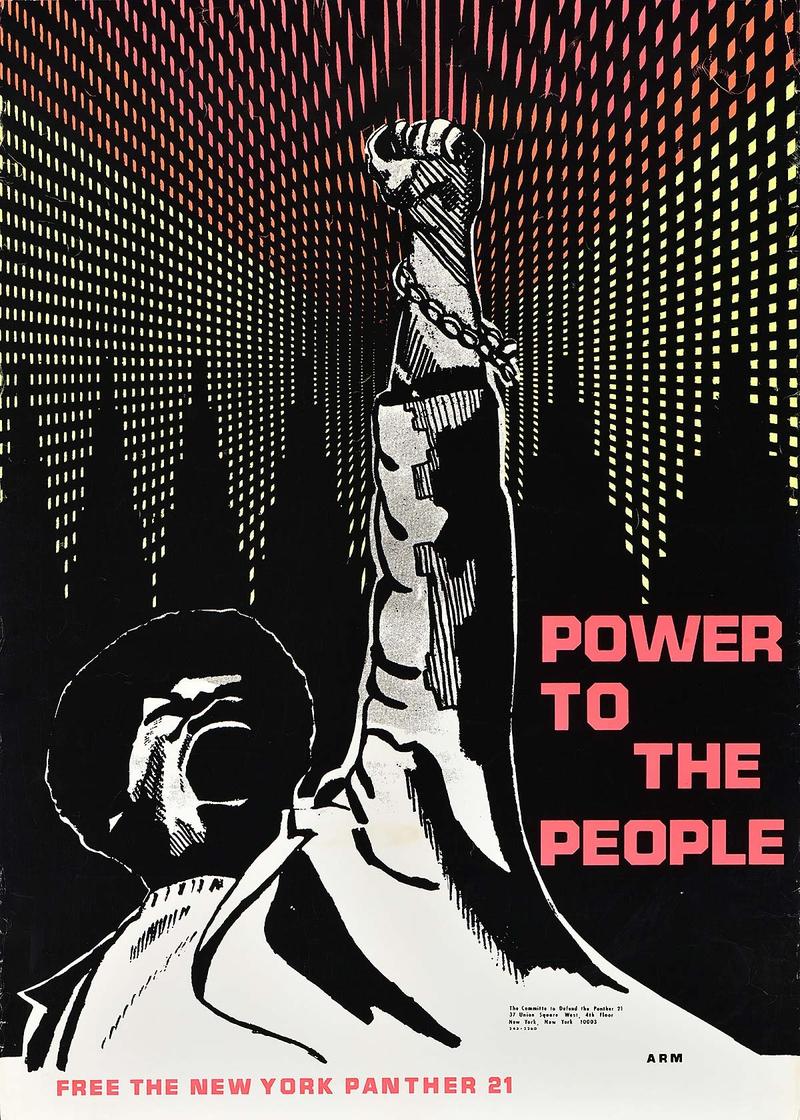

Tiffany Hanssen: This is All Of It from WNYC. I'm Tiffany Hanssen in for Alison Stewart. A new Poster House exhibition revisits the origin of the Black Panther Party while exploring its iconography. The exhibition is called Black Power to Black People: Branding the Black Panther Party. The show includes 37 works, such as images of the founder, Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton, newspapers, campaign posters, and minstrel posters dating back to 1930s, all the way through to the 1980s, all exploring the theme of Black identity and power. Time Out calls heroic images of party members and The New Yorker refers to it as graphic gems that escaped the fate of the wheatpaste bucket.

Curator and Poster House Education Coordinator Es-pranza Humphrey joins us to talk about the show at the Poster House, which runs through September 10th. Es-pranza, hi.

Es-pranza Humphrey: Hi, how are you?

Tiffany Hanssen: Thanks for being here. Great. Thank you. Thanks for being on All Of It. From what I understand, you started thinking about this back in 2020, right? I mean, we all know what was happening in 2020, but what was happening specifically for you in terms of pulling this show together?

Es-pranza Humphrey: In 2020, I actually just got the job at Poster House at that time, by the way, a week before the pandemic.

Tiffany Hanssen: Welcome to your new job.

Es-pranza Humphrey: Yes. I have a background in writing, I love to write, I was a history major undergrad, I was an American Studies major in grad school. I guess my writing really stood out to a lead curator at Poster House. She presents me with this, just like this catalogue of amazing visual pieces, and just says, "What story can you pull from this?" It starts with the idea that I wanted to track down this timeline of Black Power, how does it look in the 1890s to the way it looks today.

What I kept noticing is that the Black Panther Party was there at every turn. I would think about the Black Power Fist, and then I would trace it, and I would see the Black Panther Party uses it so powerfully. Then I would think about the Panther, and I'm looking at the Black Panther Party. It comes from this idea that the Black Panther Party is what we think about when we think about Black power, and I really wanted to dive into that.

Tiffany Hanssen: The theme is Black Power to Black People. I'm sure that's intentional, so talk about that.

Es-pranza Humphrey: Yes. There is actually a poster in the exhibition. It's a campaign poster, featuring Eldridge Cleaver, who wanted to run under the Peace and Freedom Party, which was a third party. A lot of the posters say, "All power to the people, all power to the people." I knew what I wanted to look at, I wanted to look at Black Power, and that poster, in particular, said, "Black power to Black people," and that's what the exhibition was going to be about. It was for Black people, it's for the message of Black pride, it was for the message of Black Power, and that was what I needed to make a statement about. The minute I saw that poster, I was like, "This is going to be the title of the exhibition."

Tiffany Hanssen: When you walk into this exhibit, I guess, I'm curious where that poster is, but also, I'm curious about how you've laid out the entire exhibit. When people come in, what do they see? Is it just a timeline, or how's it laid out?

Es-pranza Humphrey: You're right. Like I said, originally, I wanted this timeline. I thought it was going to be this beautiful chronological sequence, but it became a thematic sequence because I noticed that there were specific things that made Black Power what it was. When you walk in, you get this historical moment where you see the minstrel posters, so you really think about the image of Black America, who's in control of this image at the time, and minstrelsy is not in the full control of Black people, but it's coupled with a photograph of Huey in his peacock chair. He's stoic, and he's attentive, and he's armed, and he's in the Black Power, the Black Panther uniform, that militant uniform, so he now owns that image. I frame it in that way.

As you move through the exhibition, you think of all these themes that make Black Power what it is, this particular poster, the campaign poster with Eldridge Cleaver, is in the politics of Black Power section, which is this vibrant red wall. It's thinking about how they deviate from the two-party system, which is a conversation that we have today, where we're we're thinking, what does it look like to support a third party?

Tiffany Hanssen: I want to go back to this first image that people see when they come in. You're talking about this poster that's from the minstrel era, so we're talking about '40s. You're juxtaposing that with an image of-- and it's not a poster, right? Is it a photograph?

Es-pranza Humphrey: It's a poster.

Tiffany Hanssen: It's a poster of Huey Newton. You're saying there's a little bit of our power being taken away, and also, reclaiming a little bit of our power. Is that really the message you're sending with that adjacency there at the beginning of the exhibit?

Es-pranza Humphrey: Right. I wanted that first part to pack the punch of this is how we've always been perceived. It's in the eyes of somebody else, it's in the eyes of white America, it's in the eyes of Black actors having to put on Blackface as well. I didn't want it to be too vulgar of an image. I know the emotional labor that it takes for Black people to move through Black content. I found this circus-- it's actually a circus poster, and circus posters at the time were very vague because they're meant to adapt to whatever the next show was going to be. We found this circus poster, it's huge, but I think it's--

Tiffany Hanssen: What do you mean by huge?

Es-pranza Humphrey: It's really big. On the wall, it's actually--

Tiffany Hanssen: By feet.

Es-pranza Humphrey: Yes, by feet. I don't know the exact measurements, but it's pretty big.

Tiffany Hanssen: Because in my brain, I think posters like-- I don't know.

Es-pranza Humphrey: Right, and so we got it, and we were like, "Oh, wow, this is like almost my height," and I'm 5'2", so it's almost my height. The point was that even if that is a big poster, even if it is a circus poster, even if it shows minstrelsy, I didn't want that part of the exhibition to take on that emotional labor for Black people, to look at him and not even want to go through the exhibition.

I think it makes a statement it needs to, and Huey is right next to it. It kind of overlaps that poster, actually, which is an amazing design feature because now he has the power. Then we blew up the image of Huey in the peacock chair next to it as well. That just sets the framework, but there's so much more power in Huey in his peacock chair.

Tiffany Hanssen: We're talking about the minstrel eras, '40s, I want to fast forward to the '60s, the Black Panther Party officially formed in October of '66. Help us with a little history for people who may not know. What were the conditions that led to the formation of the Black Panther Party?

Es-pranza Humphrey: This is actually a really good question because I also teach at the museum, so it's always good to frame that conversation and to think about, this is the tone that's at this time.

Tiffany Hanssen: Absolutely, right.

Es-pranza Humphrey: In the 1960s, a lot of us think of, okay, we're cutting off of that tail end of the civil rights movement, the formal civil rights movement, and Black people are fed up with having to ask for permission. I don't fully subscribe to the whole civil rights movements only about asking, there was so much radical movements within the civil rights movement.

In this general idea, they're thinking about how do we make that shift to Black is beautiful to Black pride to really showing that Blackness needs to be solidified and that the Black Power movement is this powerful statement about, we are completely pro-Black and we're going to show you why. That's really the tone that we're taking. The need for this Black nationalism or this Black international movement comes from thinking about, what do politics look like? What are things that we're being protected under, and what are things that were not being protected from?

Tiffany Hanssen: What were the goals at that point of the Black Panther movement?

Es-pranza Humphrey: Community development. They wanted to make sure that there was no need to go outside of our community to find help, so that's where you get these free breakfast programs, that's where you get these health clinics. There's also this need to understand that the hair that grows out of your head is beautiful, and so no need to press it in a certain way that's not natural.

You get this natural hair movement, you get this Black powerful style, this Afro style that comes out of the embracing of this style. Also, the willingness to defend your community. The police aren't doing their job in this time period. They're not doing their job, and what does it look like for Black people to defend our own communities?

Tiffany Hanssen: This is a show focused on images. One of the images that a lot of people are familiar with is the Black Panther Party's logo. First, if you're not, just describe it for us.

Es-pranza Humphrey: The Black Panther Party's logo is a panther, and it's like coming at you in a way, it's more forward-facing than it is like side-facing. You see claws on it.

Tiffany Hanssen: Like a little 3D action.

Es-pranza Humphrey: Right, there's some movement to it. It's fully Black. It's a full Black Panther. It's on every poster or almost every poster, I should say.

Tiffany Hanssen: This logo was designed by Ruth Howard, who was a member of the Atlanta branch of SNCC, which is the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Communications Office for people who don't know. She was Atlanta, based in Atlanta. She was with SNCC. She worked on it. She also, actually, what's the connection there was Clark College's mascot.

Es-pranza Humphrey: Right, so Clark College was what we know today as Clark Atlanta. It's an HBCU, Historically Black College University. She was focused heavily in the Atlanta branch but the Lowndes County Freedom Organization was looking for-- on the ballot, you had to have something, a symbol to represent your party because for people who couldn't read, but also, at the time, the Democratic Party symbol was this white rooster, this rooster. It stood for white supremacy.

They go to Ruth Howard and just say like, "What can we create?" Originally, she creates a dove. That doesn't pack as much of a punch. The panther comes, it goes down the line. It's a big game of telephone. I read this online, it's like this big game of telephone. It gets into a few people's hands, but three women aren't mainly credited for it. The next woman is a white Jewish woman, Dorothy Zellner. She gets it in her hands, cleans it up. Her husband also has a say in it as well.

They actually find out that Ruth Howard was the first at that time to really give us that panther. Then, eventually, goes to Lisa Lyons. She cleans it up as well. I think she adds an extra claw or something. It's for campus posters. Also, it should just be known that, by then, the Lowes County Freedom Organization's Panther was so well known that it wouldn't have been unfamiliar for someone to say, "Hey, could we use this?" That's exactly what ends up happening with Huey. It's like, "Hey, can we use this?"

Tiffany Hanssen: All right. You ended up speaking in preparation for this exhibit. You spoke with Black Panther Party members. What insights did they offer you as you were pulling together all of these images?

Es-pranza Humphrey: This was probably my favorite part of the research process. I got to speak to, actually, Emorey Douglas, who has an amazing recollection of all these really precious moments. He explained a lot of his process with the limited resources that they have. They're young at this time. They don't have all the wealth in the world to just spend on creating this visual design. With these limited resources, Emorey Douglas creates this powerful iconography, these powerful images with the help of many other people. A lot of people forget that there are women in the design process of this organization as well.

Tiffany Hanssen: There are a lot of women in the Black Panther Party period.

Es-pranza Humphrey: So many. I had the pleasure also speaking to Dr. Rosemari Mealy. She was horrified by the image of Fred Hampton during her early days. She said, "You know what, I want to commit myself to this party." She does this amazing work of talking to people who have issues with their landlords and speaking to landlords about how unjust the system of housing is. She really was an amazing asset. Just her insight about women in this party, like I had so much fun speaking to her because it was such an informative experience to speak to a woman who talks about how important women are in this party, very, very important.

Tiffany Hanssen: On that, there's an image in the show that features two women armed with an axe, a gun, a grenade. It's titled, correct me if I'm wrong, No More Riots Two's and Three's, and that's from the '70s. What does that say? What does that image say about women's involvement in the Black Panther Movement and what role they took on?

Es-pranza Humphrey: That's an Emorey Douglas piece. He makes it very clear that he knew, from the very beginning, women are a vital part of this, and therefore, he's going to depict them in militant ways just as he would depict the men in militant ways. That particular poster exemplifies that. These are women who are also going to arm themselves, and No More Riots Two's and Three's speaks to this idea of, we're going to do this in militias, essentially. We can get this job done in twos and threes, no more riots. We don't need to make these big, big bold groups going and trying to make this change. We're going to do these in small little militias.

I think by putting women on that particular poster, it just integrates women into the story in a seamless way because we know that women were defending the Black community but also they would have to go home and do a lot of the caregiving to children, to their families. Emorey Douglas also mentions that it's important that women are doing a lot of other jobs aside from being militant, but they're also revolutionaries.

Tiffany Hanssen: Well, one of the women that we absolutely have to talk about when we're talking about this is Angela Davis. She wasn't an official member of the Black Panther Party, but she was an important figure, no doubt. How would you describe her relationship to the party?

Es-pranza Humphrey: I think that what I noticed by curating this exhibition, because again, we're thinking of visual language, we're thinking of the way that images communicate something. I realize that her likeness is what makes her a very symbolic part of the Black Power Movement, and in turn, the Black Panther Party. She's wearing her afro style. She's an amazing orator. A lot of the images that we have in the show are her orating like she's in motion. She's making a speech, she's making a statement, and they're rallying.

Tiffany Hanssen: Like at a podium.

Es-pranza Humphrey: Right. It's something to say because she's one of the only people that are really always caught in that motion. My favorite poster in the exhibition is actually a campaign poster where she's not even running for any specific campaign, but Hall and Tyner actually end up using her image for their campaign poster and use it in the foreground of The Declaration of Independence is in the backdrop. It's called Angela Davis urges you to declare your independence. It just shows she's not even running for this campaign, but she's such a powerful image. They had to use her.

Tiffany Hanssen: The Black Panther Party had its own press. I imagine, do you have newspaper images in the exhibit?

Es-pranza Humphrey: We do. I have a fun fact about the newspaper. When you research, you should never go in with a specific question because then that limits you. I knew I wanted to focus on visual language. I start reading through all these newspapers, and I found these two posters, and they were really nice, but there was nothing that I could really find about them. I'm reading through all these newspapers, and I find out that at the very back of every newspaper, they sold these posters.

They would sell them for about $1 in California, $1.25 outside of California, sometimes for less than that. I saw some for ¢50, but they had these posters on sale. The back section of these newspapers were for art. It was for this visual culture because they knew that these were going to make a statement. They knew that they needed to be put up in streets or in the windows of headquarters.

Tiffany Hanssen: Well, having your own press helps you control the narrative. Why was it important do you think for them to be able to control the narrative, and them, I mean the Black Panther Party?

Es-pranza Humphrey: They're not the first ones to have a newspaper as an organization. They're very effective because what you see in those newspapers is that they're naming things for exactly what they are. They're calling Black Panthers who are in prison, political prisoners. They're naming things, they're naming exactly who the enemy of the revolution is. They're saying like pig is for anyone who abuses justice.

They're giving you the language that you need to identify this collective message of Black Power. Then most importantly, they're humanizing their members. They're humanizing revolutionaries. You're not going to see people that are in these horrible depictions of what the newspapers would probably put them in.

Tiffany Hanssen: That was my next question. What would you see in the mainstream newspapers then?

Es-pranza Humphrey: You would probably see like it's similar to what we see today where it's like a Black person might do something and they choose the absolute worst picture. They'll probably choose a mugshot or something like that. Just these images that put the Black person in a position where they are now the villain of this tragic event.

Tiffany Hanssen: What kind of language's around that?

Es-pranza Humphrey: Let's just say, former convict-

Tiffany Hanssen: I see.

Es-pranza Humphrey: -does like something like that, like very villainous language, very pejorative language. What the Black Panther Party is doing is they're placing the humanity first for every revolutionary.

Tiffany Hanssen: People who come to the show, they may not know much about the Black Panther Party. What do you hope they're going to take away from this?

Es-pranza Humphrey: I always say that there's two messages. I want specifically Black people to walk into this exhibition and understand that this is a safe space and that Black Power is transcendent. By looking at the Black Panther Party, we can start to understand our own activism and we can start to just embrace the love and the power behind Black Power. Then for the general audience that comes around, I want them to understand why Black power is so important.

It's a moment in history, but it's something that we are still seeing today. It's important to understand why iconography is important. Visual language, everybody can speak visual language. At Poster House, we have vibrant verbal description tours because even if you can't see it, if I describe it to you, it still holds down.

Tiffany Hanssen: There is audio as part of this. I have queued up here, some Elaine Brown Seize The Time. Audio is important to this exhibit.

Es-pranza Humphrey: Yes. This is playing throughout the gallery, and it is so powerful. Elaine Brown sings these songs on the record and it's powerful.

Tiffany Hanssen: Es-pranza Humphrey, thank you so much for your time today.

Es-pranza Humphrey: Thank you so much.

Tiffany Hanssen: Es-pranza Humphrey is the curator at Poster House, and she's their education coordinator. The new Poster House exhibit revisits the origins of the Black Panther Party while exploring its iconography.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.