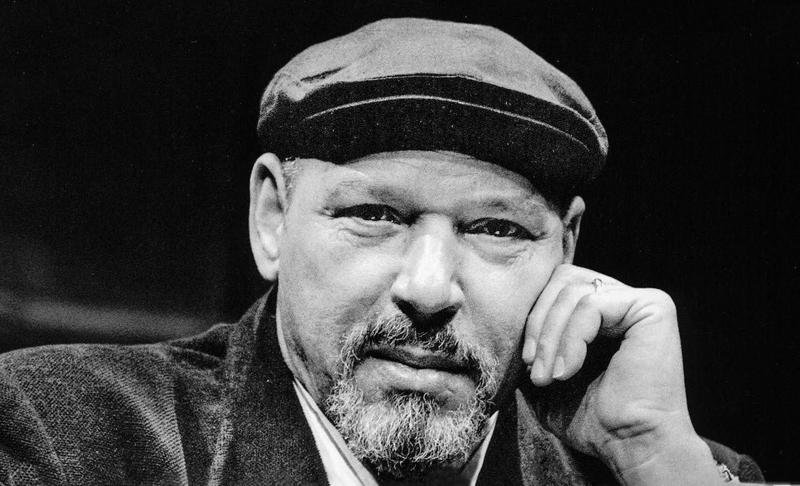

How August Wilson Wrote 'Fences' and His Success on Broadway (Full Bio)

( Courtesy of Netflix )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios in SoHo. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. If you couldn't share every day with us and you missed any segments from past shows, you can always go back and listen. We kicked off the week we had a great conversation with director Todd Haynes about the craft behind his new real life inspired film, May December, starring Julianne Moore and Natalie Portman. I believe it opens tomorrow.

We also talked to Black Thought of The Roots about his poignant new memoir. We spoke to the founders of the Borscht Belt Historical Marker Project and heard stories from listeners who grew up going to upstate summer retreats all through the height of the Borscht Belt. You can find all of those conversations on WNYC's website or you can get it on the All Of It podcast, along with the first couple of installments of this month's Full Bio series on August Wilson, which we continue now.

[music]

This week we've been discussing the book August Wilson: A Life for this edition of our book series, Full Bio. Author Patti Hartigan has been our guest. Thus far we've talked about August Wilson's evolution from high school dropout to teenage library dweller to playwriting autodidact to theater revolutionary. We have not discussed his family much because, well, this is how Wilson described his view on work-life balance to Ed Bradley on 60 Minutes in 2002.

Ed Bradley: Have you made sacrifices to do what it is that you do in terms of your family life?

August Wilson: Oh, absolutely. All my life I made sacrifices for the work. To me, ultimately, the work is the most important thing, because that's how I live. That's what keeps me here, and that's the whole purpose of my life, and I fit everything else into that. Family, of course, comes second actually to the work.

Ed Bradley: That could be tough for the family to hear.

August Wilson: Well, absolutely, but this is a reality. Art first, life first.

Alison Stewart: August Wilson married three times. First, in 1969 when he lived in Pittsburgh, he married Brenda Burton, with whom he had a child named Sakina. They divorced in 1972. Wilson moved to Minneapolis, and in 1981 he married Judy Oliver, a social worker. He became famous during their near decade together. When they divorced in 1990, Wilson released a statement that claimed he had only been home three months a year during the last five years of the marriage, adding, "It's real hard to maintain a marriage and do the work at the same time. I was never there for her."

Wilson also announced that he would move to Seattle. That's where he settled with his third wife, costume designer Costanza Romero and their child Azula. They were married from 1994 until his death. Wilson also had some difficulty with interpersonal relationships, not of the romantic kind. He famously butted heads with the actor leading one of his most famous productions, James Earl Jones. Also Wilson's inflexibility about who could direct the film versions of his work kept many of his plays from the big screen. This is where we pick up Our Full Bio conversation about August Wilson: A Life.

[music]

Perhaps August Wilson's most lauded play. It won the Pulitzer, it won the Tony, Fences. There could be a whole dramatic play around Fences and the making of Fences and all the different characters that intersected with Fences. Let's start with James Earl Jones in the lead. He had a lot to say about the script. From the reading of your book it seemed that he and August Wilson disagreed quite a bit.

Patti Hartigan: They did. James Earl Jones was pretty direct, and he said he didn't like August Wilson. He said that August Wilson didn't like him either. James Earl Jones did want to make some changes to the play. He had a lot of opinions and he wasn't shy about sharing them.

Alison Stewart: Was this unusual behavior on James Earl Jones' part? For an actor of his stature at that time?

Patti Hartigan: No, I don't know. I think in any production everybody has a lot of opinions, but August Wilson was adamant and this was a real turning point for him, that he had final control over his work. James Earl Jones and the producer had different ideas. August Wilson was a very stubborn man. When he didn't want to do something, he wasn't going to do it. He was going to stick to his guns. It was a very volatile pre Broadway run, shall we say, in San Francisco.

Alison Stewart: it wasn't a secret. That's something I found interesting. It seemed like everyone knew that the playwright and the actor did not get along well.

Patti Hartigan: Well, people within the production knew, but people from the theater who I've known for several decades had heard rumblings about this story, but never knew what parts of it were true and what weren't. Within the production, sure, they knew when there were moments where there was a lot of anger and some yelling, and they fired Lloyd Richards briefly. Who fires Lloyd Richards? They fought about the ending and they fought about-- Wiithin the production, you couldn't not know, but in the outside world, it won the Tony Award. It won the Pulitzer Prize. Everybody applauded and got standing ovations. It was his most financially successful play.

Alison Stewart: It was a play that it took decades past Wilson's death to get to screen. It's a really interesting reason. Please correct me if I get any of these facts wrong, Eddie Murphy got the rights to Fences.

Patti Hartigan: He optioned the rights. Yes.

Alison Stewart: August Wilson was really demanding that there be a Black director?

Patti Hartigan: Yes.

Alison Stewart: That seemed to be the hurdle to getting Fences made. One of the hurdles. Explain what happened.

Patti Hartigan: Well, he said that at his first meeting at Eddie Murphy's mansion. Remember Eddie Murphy, he was at the top of his game at this time.

Alison Stewart: This is 1987?

Patti Hartigan: Yes. In high, high demand. He optioned it and August Wilson just said, "I want a Black director." Then they had a back and forth where I think, according to Wilson, in a piece he later wrote, Eddie Murphy said, "I don't want to hire someone just because they're Black." August Wilson said, "Neither do I. I want to hire somebody who's good who's going to do the film."

He said that, and he couldn't get it. He didn't like some of the people they were offering him. They were offering him white directors, and he just said, "No, if it gets made, it gets made. If it doesn't, it doesn't." He felt very strongly about this one in particular, because more people were going to see the film version of Fences than had seen all of his plays, probably. He felt very strongly about him.

Alison Stewart: Well, that was a question I had, is that this is a play that so many people could see, yet he was so adamant about having a Black director. Why was that more important to him and to his legacy than getting this story to a large amount of people? Did you get a sense of why?

Patti Hartigan: Well, he wrote about it. He wrote a piece in Spin magazine, and then it was excerpted on the New York Times Op-Ed Page. It was an uproar about it, but he felt for this particular movie, he felt that in order to direct it, you had to be a member of the culture that it depicted. He felt very strongly about that. That's why he kept saying no. When he didn't want to do something, he didn't do something. When he made up his mind about something, he stuck to his guns. it was really important to him. Then you wait, and what is it? 2016 from 1987? You need someone with the wattage of Denzel Washington to finally be able to direct the film and get it off the ground.

Alison Stewart: What were other instances when August Wilson did allow his work to be televised or to be reconsidered for screen.

Patti Hartigan: The only other one was the teleplay of The Piano Lesson, which was a Hallmark television film.

Alison Stewart: How involved was he in the making of that?

Patti Hartigan: Very. I think he has a credit as a producer on that. It was filmed in Pittsburgh in 1994.

Alison Stewart: Did he consider that a professional success?

Patti Hartigan: He never really talked much about it. I'm sure when it aired, there were millions of people watching it, again, more than had seen his plays. He did feel great, because he was finally on television and he could speak up to his mother in the Heavens and say, "I did it, Ma." You can find it. There's a really grainy version of it on YouTube. I don't know. It's very much by the book. He didn't really talk about that actually to tell you the truth. I think as he got closer to the end of the cycle, the goal was to get those plays on paper, because he said he was writing 10 and he was going to write 10. That hung over his head a lot. There were so many other things he wanted to do. He had the beginnings of a novel. Wouldn't you love to read an August Wilson novel? He talked a lot and laughed a lot about a play he called The Coffin Maker Play, which had a crazy cast of characters. Kind of like Black Burton including Queen Victoria, and the coffin makers were fighting with the undertaker as in they were all on strike and that was the premise for the play. That's all I know. I never- I haven't read any more of it. I've seen some notes.

I think rather than focus on the film medium, he really wanted to finish the cycle, and can be a- get an impediment. It can get in the way if you're thinking about Hollywood. He also felt, and he said many many times, he was offered screenwriting opportunities by major directors and he turned them all down, because he knew too much about playwrights who had gone to Hollywood and then they never wrote another play.

Alison Stewart: Hey, wasn't he offered to write about Amistad?

Patti Hartigan: Yes. Yes, according to his attorney. Yes.

Alison Stewart: Let me ask you about his attorney. That's quite a nice segue.

Patti Hartigan: Oh.

Alison Stewart: John- is it Breglio?

Patti Hartigan: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Who was and still is a powerful entertainment lawyer and producer? Why did someone like August Wilson need a John Breglio in his life?

Patti Hartigan: Well, after the non-review ran in the New York Times after the [unintelligible 00:12:01] production of Ma Rainey he started getting all these offers, and he had two different agents. He was furious when he got that offer to turn Ma Rainey into a musical and he wasn't having much luck with agents. It was actually Benjamin Mordecai and Lloyd Richards who introduced him to his attorney, because he needed somebody, but he didn't want an agent anymore. John Breglio became really quite protective of August Wilson. Serving like an agent, but also serving for contracts and things like that, anything legal. That’s how he got it. It was August Wilson saying, "I don't like agents and I'm not doing it the way everybody else does it."

Alison Stewart: We’re discussing August Wilson: A Life. It's our choice for Full Bio, my guest is Patti Hartigan. At the height of his success, in the '80s. It's the late '80s, he's got that one run where he's got Fences on Broadway, and Joe Turner's at regional theatres, and The Piano Lesson is going to debut at Yale. Who were his friends? Who was around him at this time? Who were his peers?

Patti Hartigan: The late '80s. Well, Claude Purdy. The late Claude Purdy was a director who had worked all over Europe. He moved to Saint Paul when Penumbra Theatre was found and he convinced August Wilson to move to join him there. This new theatre, it's all about us, and those two were tight during that period. The poets that come in Pittsburgh where he was just still very tight with him but he was living somewhere else. He was hearing the voices of Pittsburgh but he was living in Saint Paul. He always had a group of male friends later when he moved to Seattle. The great novelist Charles Johnson was his dear friend. How much time did he have? He didn't actually go to parties. He didn't go on vacation. He was really just directed.

Alison Stewart: Yes, it's interesting, you know as we've been talking about his career. We've talked very little about his family or his personal life and you know on his gravestone it says, "Playwright and poet above father and husband and family member." There's this 60 Minutes interview he did with Ed Bradley and they seem very comfortable and at the end, he says, "Yes the work comes first. Family comes second."

Patti Hartigan: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Did you find that to be the case in your research?

Patti Hartigan: I did find that to be the case. He truly cared about and truly wanted to be more involved with particularly his children, but again the work came first and it's a price someone like that pays. In my prologue, I tried to create a cinematic scene of him at the height of his career and near the end, and looking back in his hometown of Pittsburgh that he had done all these things he said he was going to do but what did it cost him? I think family might have been a little bit about that but he-- I also have heard stories from people who interviewed him answering the door in a birthday hat. Those pointy hats, because it was his daughter Azula's third birthday and I think maybe his wife at the time had left to go get the cake or something and he was stuck with 15 three-year-olds. He's like, "Come on in we're having a party here." Yes, it's a rough thing. It's a rough thing for any artist who makes that kind of choice, especially because he set the bar so high for himself. Yes, he would admit absolutely that the work came first.

Alison Stewart: And just so we're clear, would you run through his marriages and his children? I feel like we should say their names out loud.

Patti Hartigan: Yes, sure. His first wife was Brenda Burton who was in-- They were very young. They were in Pittsburgh and they had Sakina Ansari Wilson was their daughter who was born around 1970. Was it '70? That ended because August was-- they had actually been evicted from their public housing and she filed for divorce. He was working all those odd jobs and working at the theatre until late at night and poetry wasn't paying the rent. She went on to nursing school after that.

When he moved to Saint Paul he met Judy Oliver who was a white social worker. They were married for many years and she was his muse. She wrote the grants. She sent the grants off and they split up in 1990 and then his third wife is Constanza Romero who he married in- and they married in 1994, but they were living in Seattle together before that. They have one daughter, Azula Carmen.

Alison Stewart: Do his children carry on his legacy? The mantle of August Wilson my dad the playwright? Or is he just dad?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, that's an interesting question. I think for Sakina, she's older, I think it's a little of both. He's dad first. He's definitely dad first, but they honor the work. Yes, sure and the legacy is so important.

Alison Stewart: On our last installment of Full Bio tomorrow we'll hear about the famous verbal showdown between August Wilson and famed literary critic and educator Robert Brustein that took place live in front of an audience at the Town Hall on 43rd Street right here in New York City.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.