The History of an Upper West Side Cult

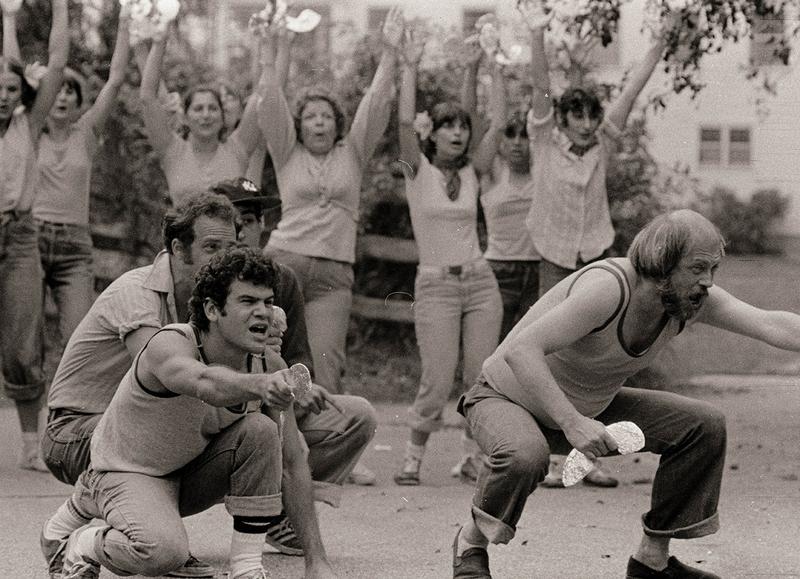

( Donna Warshaw )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It from WNYC. I'm Allison Stewart. You may have walked down West 91st Street or had a cup of coffee at the Metro Diner at Hundredth and Broadway, or maybe saw some theater on East Fourth Street and never suspected that at one time on these blocks, a psychotherapy cult was in full swing. During the late 50s, the mid-late 1980s, they were officially called the Sullivan Institute, but more casually, they were known as the Sullivanians, and they are the subject of a new book.

The Sullivanians believed in the abolition of the nuclear family because, in their view, children in a nuclear family were essentially owned by their parents in ways that led to mental health issues down the line. Monogamy too was a form of ownership that needed to go, so there was mandatory polyamory. The result was psychological manipulation, forced alienation and isolation, highly regimented sexual encounters, pregnancies decided by organizations' leaders, children sent to boarding school against their will, and a few very brutal assaults.

To hear how the Sullivanians got their start, how they met their end, we are joined by Alexander Stille, journalist and author of The Sullivanians: Sex, Psychotherapy, and the Wild Life of An American Commune. Alexander, nice to see you.

Alexander Stille: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Alison Stewart: What was it about New York City at this moment in the mid-1950s that provided a fertile ground for an organization like this to establish itself and then even to begin to thrive?

Alexander Stille: I think a few things go into it. Number one, New York was the psychotherapy capital of the world, probably according to Time Magazine, there were more shrinks in New York City than in all of the United Kingdom. This was maybe the high point of the hegemony of the traditional family. It was the era of Ozzie and Harriet and Father Knows Best, and underneath that conformity was a desire for rebellion and for searching for something more, and so I think the time was ripe for that.

You had a couple of maverick shrinks who developed an alternative idea of psychotherapy that, as you indicated in your introduction, was based on the idea that people grew through exposure to other people, and therefore, the family, by definition was limiting. Monogamous marriage was limiting. You needed to expose yourself to many people, people who weren't your family members. They began to encourage their patients to live with each other, maintain multiple sexual relations with people.

This drew a lot of if you think back Jackson Pollock was an early patient, the famous critic Clement Greenberg, and a lot of the artists that he championed became patients because this was, I think, a liberatory message. The idea that you could be free of all of society's constraints to become the most creative person you could become. That was a very appealing message. It gradually morphed into something more controlling.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, do you have any ties to or experience with the Sullivan Institute from the late '50s through the eighties? Maybe you lived on the Upper West Side and have acquaintances who were involved, or maybe you were involved yourself, or maybe you saw one of the plays put on by the Group's Theater Company Fourth Wall. Give us a call and share your experience to help tell this story about this group on the Upper West Side. Our phone lines are now open. 212-433-9692. That is 212-433-WNYC.

You can also text your message to that number and we can read it on the air, or you can hit us up on our socials @allofitwnyc. Looking for you to join this conversations about the Sullivan Institute and the Sullivanians. Alexander, this has been written about here and there. When you began your research, where did you start? Then how did the process evolve over time as you started to realize exactly what was happening in this cult?

Alexander Stille: There were articles that were a flurry of articles that came out in the late '80s when a woman who was in the group who had been denied access to her daughter kidnapped her own infant child off of the street on Broadway at 100th Street. There were a series of legal battles that generated some stuff, but at the time, the group was still operating and it wasn't really possible to get under the skin of the whole thing, and then everybody forgot about it.

When I began working on it in about 2018, people who'd been in this group were in their late 60s, early 70s, maybe 80s, and you reach a point in your life where you're much more willing to talk about. The group was very secretive during the life of the group. I hit, I think, at a good moment where people were willing to reflect on their past. I simply began-- I found a former member had written a PhD dissertation, which became an academic book about the group. I contacted her and she was invaluable. Her name is Amy Siskind. Her husband had turned out, had been a therapist in the group as well as a patient.

He became actually a major character in the book. Then just one thing led to another. I ended up interviewing about 75 people. I turned out as often happens when you get involved in this, it turned out I knew somebody who'd been a group member, a really accomplished artist who was one of those people that was brought into the group along with all these other artists that Clement Greenberg brought into the group in therapy. It just grew. I didn't think I was initially going to do a book, but soon, I was finding it so incredibly compelling and interesting, and the number of interviews kept multiplying that I decided that I had no choice but to do it as a book.

Alison Stewart: Will has tweeted to us, ''How can we find out the addresses where Sullivanians lived? Friends of mine used to live in a huge eight-bedroom apartment on West 98th Street, and often said it was created by a commune and cult.''

Alexander Stille: I'm pretty sure that was a Sullivanian apartment. They had a number of apartments. I forget the exact address, but it was on West End and 98th Street. That sounds just right. It's funny. I ended up, for example, a colleague of mine, I teach at the Journalism School of Columbia, turned out that a colleague of mine had lived in one of those buildings. When her son was a small child, his favorite playmate was a little boy who was growing up in a Sullivanian apartment.

They would always get together, and then mother would never be there because they wanted to separate the child and parent as much as possible. The child would always be accompanied by a babysitter. At the same time, he had far more toys and things thrown at him than any other child she knew. There was this weird combination in which they were overcompensating for the lack of parenting by lavishing stuff on their kids. That kid, as I later learned, she'd always wanted to know what happened to this little boy. He was taken from his mother, and then taken from his father and raised in a group apartment.

Alison Stewart: I don't mean to be crass, but often when you think about these cults and the cults that we've seen in the past few years, there's an element of money involved. Somebody is making money, somebody is doing this to benefit themselves. Is that the case with the Sullivanians?

Alexander Stille: Yes and no. It wasn't really -- I don't think it was principally motivated by money, but there's no question that money was moving up the pyramid in the sense that you had ordinary members who were patients who were seeing therapists two or three times a week, maybe more. Often, for example, some people I interviewed shared their date books and their diaries with me, and they would have their monthly expenses and you'd see that about a third of their income was going to therapy.

That money is going up to their therapist. That therapist in turn is supervision with one of the four leaders. The money is rising up the pyramid. Some of the patients would make deals where they would clean the houses of the lead therapist in exchange for a break on their therapy bill babysit for their kids. There was a lot of services and money that was going up the pyramid to the top. The top leaders didn't live especially lavish lives, but they'd also never moved a muscle to clean their house, to make their meals. They had a cook, they had cleaning people, they had babysitters.

They sent their kids to the best schools and the best private schools in New York City, Dalton, and Trinity, and places like that. All that was where the money went, but it wasn't-- At a certain point, Saul Newton, one of the two founders, bought a house in Vermont, which scandalized people in the group because this was supposed to be a communitarian egalitarian group. What is he doing? Where's he getting the money to buy a nice country place in Vermont? Otherwise, it wasn't really about luxury. It certainly was about privilege.

It was very hierarchical and it was very clear who had the power and therefore who enjoyed a greater privilege. For example, the four leaders were the only people who were allowed to live with their spouses and their families. Other people were living in single-sex apartments. Single-sex so couples didn't form permanent family units. Time with children was greatly limited. The leaders instead lived in a big house with typically separate bedrooms so they could continue seeing multiple sexual partners, but their spouse got to live with their kids, which was a privilege other people didn't have, and they didn't have to be in therapy. Everybody else had to be in therapy.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Alexander Stille. The name of the book is The Sullivanians: Sex, Psychotherapy, and the Wild Life of an American Commune. Let's talk to Elizabeth, who's calling in on line one. Hi, Elizabeth, thank you so much for calling WNYC.

Elizabeth: Hi. Hi. Boy, is this a topic down memory lane? I came to New York to go to university in 1969 and met someone who became my roommate, a woman, in 1970. We shared in common that we were socialists and she wanted to introduce me to this Sullivanian group. I had my own therapist at the time, which greatly bothered her. She had a boyfriend who I would say was 15 years older than her, who came to our apartment after a therapy session with a Sullivanian.

He cut his wrist, not sharp enough to kill himself, but to bring out blood, and he wrote on our apartment wall, ''I hate my mother.'' I shortly found out that having a decent relationship with your mother was a no-no. That's why she told me one day on a bus that I could no longer be her roommate.

Alison Stewart: Elizabeth, what a wild story. Thank you so much for calling in. Does what Elizabeth say tracks, Alexander?

Alexander Stille: Yes. It's interesting because that particular story I'd not heard, but it doesn't surprise me. The business of, ''I hate my mother,'' Jackson Pollock, when he went into therapy began to refer to his mother as the old womb that's a tomb. In other words, that your mother is essentially a death trap. As your caller indicated, if you didn't have a sufficiently dark presentation of your family life, you were thought to be lying. You were thought to be kidding yourself, whitewashing your past.

Often, the therapist would help patients write letters to their parents saying, ''You've ruined my life. I want nothing more to do with you. I will not be in contact with you.'' It led to, in many cases, people breaking with their family for 15 or 20 years. In some cases, people came out of therapy when the group finally disbanded to discover that their parents had died. They knew nothing about it.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Diana on line two calling in from Manhattan. Hi, Diana. Thank you so much for calling All Of It.

Diana: Thank you. I love your show. You're great. In the early '80s, I studied acting with a very famous actor who lived on the other West Side, was married to a therapist, his wife was a therapist. He went to therapy, not with his wife, three times a week. He had very unusual ideas, I must say. He later became even more famous. He'd been doing features up to then by starring in a well-known television series for five years. I will not tell you his name, but he thought this was just the greatest thing going.

I was not interested, and he just thought I was this pathetic, hide-bound, doctrinaire, New Jersey, Neo Virgin. I was not a virgin. I was in my late 20s, but he-- I wish him the best. He's still alive, but I was monumentally uninterested in this kind of lifestyle and commune-like adherence to authority.

Alison Stewart: Diana, thank you for calling in. This is an interest, this was one of my questions, Alexander. How did the Sullivanians recruit? Clearly, this person did not get to Diana, but how did they get people aboard, get people interested, and have them stay?

Alexander Stille: Several ways. Often, it could work in a number of different ways. People would-- you were a student, let's say, at Columbia, and you needed a place to stay and you answered a roommate wanted ad and you moved into a large and expensive apartment. Important to remember that in the late '60s and '70s, New York was becoming depopulated. Manhattan lost half a million people between the '50s and the '70s so you had these big attractive pre-war buildings with large apartments with four or five bedrooms.

You answered an ad, you moved in, you didn't know anything about it. You discovered some of the people in the apartment are in therapy. You should be in therapy. These people are fun, interesting, smart people. They have parties on weekends. Every Friday and Saturday night, there would be parties in one of these big apartments with lots of room, and they'd have music and dancing and cool people. You were a shy, inhibited 20-something person and somebody wanted to go home with you, and you thought this was great.

Or you simply asked for a referral to therapy, and you ended up with a therapist you didn't know about their background and it turned out that they had a different approach to therapy. They encourage you to go to a party, they encourage you to join a men's group, to join a singing class, or they had Lucinda Childs, a famous choreographer, was giving dance classes in this group. There were painters who were giving painting classes. They had a lot of different ways you could access this group. During the Vietnam War, therapists in the group were helping people get draft deferrals and exemptions.

There were lots of ways into it. Another avenue was Clement Greenberg, the art critic, taught up at Bennington College, and there was a whole pipeline of people that went from Bennington into therapy in this group. There were a bunch of different avenues to enter.

Alison Stewart: You mentioned one of the founders, Saul Newton. I'm going to play a clip from his daughter. It's an interview you did with his eldest daughter, among his 10 children, Esther. We'll get a sense of who he is from this clip, but we can talk about it on the other side. This is describing a hike she went on with her parents and how she responded when she, at seven years old, got a little tuckered out.

Esther: Well, first of all, he was scary. Even though he was a small man, like 5'8 or '9, but he just exuded power, certainty, I guess, sex appeal because he had so many women. He just took up a lot of space. [chuckles] We went out for a walk one day, all three of us, and on the way back, I started to get tired, and I started to whine, "Oh, I can't go any further."

I don't remember exactly what I said. He picked up a stick off the ground, and he said, "You walk this distance in front of me, and if you whine one more time, I'm going to hit you with a stick," which happened a couple of times.

Alison Stewart: How did Saul Newton's personality shape the Sullivans and the type of therapy people would get?

Alexander Stille: I think quite a bit. As Esther, who's herself a very brilliant woman who was a pioneer in gay studies anthropologist indicates Saul had a domineering personality with a strong pension for violence. That, I think, translated into his therapy. A lot of people will tell you that they were yelled at in therapy, that they were bullied, that they were made to feel less than in the therapy.

One person said like, "In the first year of therapy, the whole emphasis is on how terrible your parents were, and then the second year is how terrible you are because you, of course, are the product of those terrible parents." At that point, you've created a great vulnerability in the person where the person feels, "Oh my God, how could I possibly survive without these people because I'm such a nothing? How am I going to overcome this awful background that I have without the help of these amazing therapists?"

People recounted stories of the therapist throwing a notebook at them, yelling at them, that kind of thing. That happened, I think, quite a lot and Saul's personality informed that. Saul was incredibly good. When I tried to understand what was the thrall he had, the power that he had over people. One of them was really just that he was angrier and more violent than anybody, that he would pop up his chest and threaten to beat you up or threatened to have you thrown out, yell at you louder than anybody.

One of the things that was characteristic of Sullivanian therapy was something called a summary. A summary was when your therapist characterized your personality, and it was generally a really negative characterization. You were a mealy-mouthed, gutless piece of slime. You don't have the courage to do X, Y, and Z. That kind of thing where it would really break down a person. That I think was a way of gaining power over the patients.

One of the things that I think I learned in the course of doing this work was how powerful the process of transference that happened during the therapeutic relationship is and how devastating it can be when that relationship is abused. If a therapist uses it to get their hooks into someone and to manipulate them rather than a therapist just doing their job properly, redirects transference and lets the person know, "Hey, I'm not God and I don't have magic powers. It's not me. It's the process that's making you feel better" If instead, the therapist says, "Yes, I really am brilliant. You can't live without me," the whole process changes.

Alison Stewart: To find out what happened to the Sullivanians, you'll have to get the book, The Sullivanians: Sex, Psychotherapy, and the Wild Life of an American Commune. Thanks to everyone who called in to share their stories and thanks to Author Alexander Stille for writing the book. Thank you for being with us.

Alexander Stille: Thank you, Alison.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.