Full Bio: Shirley Chisholm's Final Years

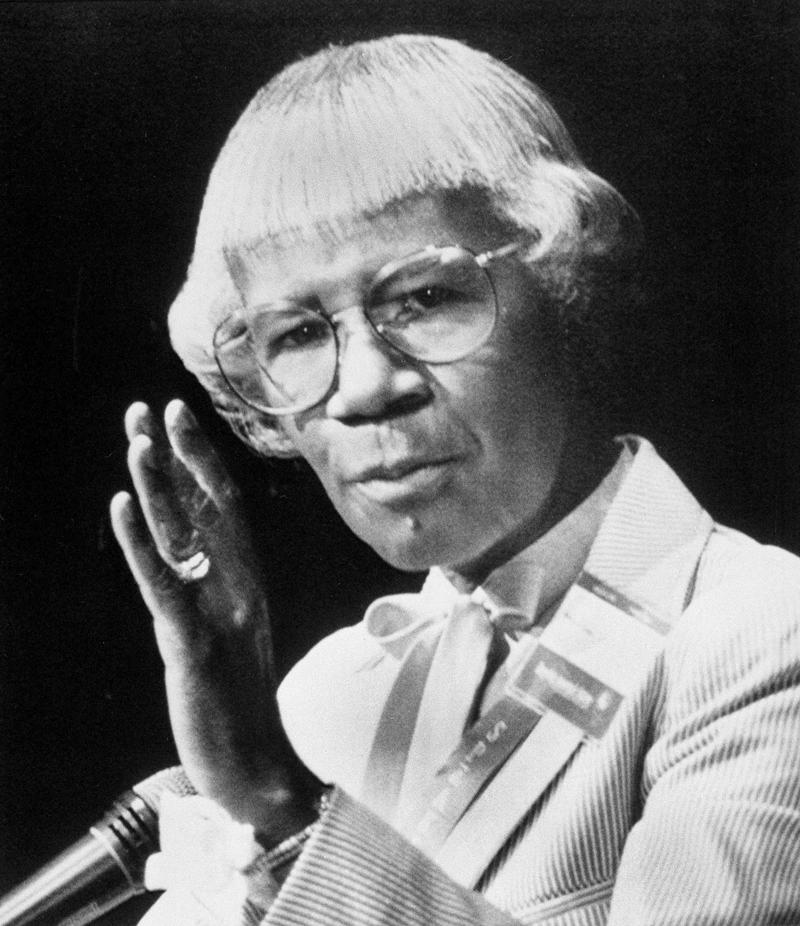

( (AP Photo/Joe Cantrell) )

[music]

Alison Stewart: We are finishing out our Women's History Month full bio conversation about a person who made history when she became the first Black person and the first Black woman to seek a major party nomination for president of the United States. Here's a clip from that day in January 1972 when Congressperson Shirley Chisholm announced her candidacy.

Shirley Chisholm: I stand before you today to repudiate the ridiculous notion that the American people will not vote for a qualified candidate, simply because she is not white, or because she's not a male. I do not believe that in 1972, the great majority of Americans will continue to harbor such narrow and petty prejudices. I am convinced that the American people are in the mood to discard the politics and the political personalities of the past. I believe that they will show in 1972 and thereafter, that they intend to make independent judgments on the merits of a particular candidate based on that candidate's intelligence, character, physical ability, competence, integrity, and honesty.

Alison Stewart: Chisholm landed on 12 primary ballots. She made enough of an impact, especially with young Americans that President Nixon's ally G. Gordon Liddy was tasked with tracking her. Two of those young Americans were the parents of our guests this week, professor and author Anastasia Curwood. In her book, Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics, she writes, "I first encountered Shirley Chisholm as a child in my own family's collection of photos.

There in black and white with a younger version of my parents was an elegant, dark-skinned woman with an infectiously broad smile. Mistaking her for my father's sister, he corrected me." "That is Shirley Chisholm. She ran for president and when you grow up, you can too." My mother had volunteered as the treasurer for Chisholm's presidential bid in Massachusetts, and while my father was a young reporter at the time, and covered the campaign. After her run in 1972, Chisholm hit her stride in Congress. In 1974, a Gallup poll named her one of the top 10 Most Admired Women in America. Here's our final conversation with Anastasia Curwood.

[music]

Alison Stewart: When did Shirley Chisholm first get the idea to run for president?

Anastasia Curwood: Well, knowing Shirley Chisholm, and as I do at this point, I'm sure it was early in her life, but when she actually starts to publicly explore the possibility was in 1971. She was at a meeting of the National Welfare Rights Organization. It's important to understand that there was an organization devoted to fighting for the rights of people on welfare, getting what was fully due under the law, to recipients of welfare.

She appeared at the conference, she gave a keynote address, and then at the press conference afterwards, she said, "Yes, I'm thinking about running for president." That's when she first said she had the idea, but I'm sure she had her eye on it for a while.

Alison Stewart: You write that she knew she wouldn't win, but this was part of something more significant, a bigger political play. What did she hope that her candidacy would trigger?

Anastasia Curwood: Yes. What she wanted was a coalition. The whole candidacy is built on the idea that you bring people together across categories. In her case, the coalition she wanted to build, the big pieces of it were Black folks and women, both of whom were more recently enfranchised than white people in general and men in general. Specifically, white men. She's trying to bring together Black people, women, also young people. Very recently in franchise, the voting age had been lowered to 18, and anti-war folks, and basically anybody who was dissatisfied with the status quo.

The idea was to bring these people together and put pressure on the eventual Democratic Party nominee and the Democratic Party platform. She run to win, but she didn't expect that she would win, and that's an important distinction. Some people said she was crazy. "She's not going to win. A woman president, that's nuts." She's saying, "No, no. I am the instrument through which the people will exercise their power." The coalition was the point.

Alison Stewart: She didn't tell many people, including some people on her staff that she was planning to announce she was going to run for president. Why would she make such a unilateral decision like that?

Anastasia Curwood: Well, her staff said she just did what she wanted.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: Anastasia, would you remind us who her competition was for the Democratic nomination and what her pitch was that you should get behind her, not them?

Anastasia Curwood: Yes. Her competition was a group of fairly established Democratic Party politicians. The eventual nominee was George McGovern, but also in the mix runner-up was Hubert Humphrey, who, of course, had run in 1968. She said about him, "He turned out to be nice."

[laughter]

They actually were allies at the very last minute of the convention. It was all white men. The guys were the ones who saw themselves as the ones who had the best shot. Someone who dropped out pretty early, was an old ally of hers, John Lindsay. He was the mayor of New York. He was mad at her for running because he thought that she would take away his votes that they would be competing for the same voters, and he thought that he should be the one who was running. "How dare she?" It was a field of white men who were the ones who were running national campaigns.

Alison Stewart: At one point, she's on Nixon's radar while she's running, and G. Gordon Liddy gets involved in operation CREEP. They give the name the really horrible name of the surveillance of her and digging into her background Operation Coal, that's awful. What were Nixon and Liddy looking for? Why were they starting to pay attention?

Anastasia Curwood: Well, they saw her as an opportunity. First of all, she'd been a thorn in their side. She's on the list of Nixon's people. Everybody in the Congressional Black Caucus was on his enemies list. They would like to harass her, and they do harass her. They also see her as an opportunity to sow discord within the Democratic Party. What Donald Segretti the lawyer and dirty trickster from the Watergate plot did was he printed up some fake stationery that looked like Hubert Humphrey's campaign stationery.

He wrote a fake press release that said that Chisholm was insane, that she was hospitalized on and off in a Virginia insane asylum, where she was wandering around speaking gibberish, committing all sorts of indecent acts, and that this was intelligence that the Hubert Humphrey campaign had discovered and they sent it to several media outlets. Of course, the idea was to try to get Chisholm and Humphrey's campaigns mad at each other, but also it was pretty clear that it was fake because Humphrey's campaign would say, "Look, this is fake, we did not do this."

Then there would be suspicion about the McGovern camp. "Did the McGovern camp do this and put somebody up to this?" The idea was to sow chaos and division within the Democratic Party, and it was one of several tricks, as we say, that happened during Watergate.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Anastasia Curwood. The name of the book is Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics. It's Our Choice for Full Bio. I'm curious, during this period between '68 and '72, while she's in Congress and as she's gearing up to run for president, what was her relationship with the Civil rights leaders at the time? Malcolm X and MLK both are no longer with us. People who are starting to lead the Civil Rights Movement are a little more, some people call them radical, some people call them a little more pure, little more intense, however, you want to characterize it. I'm curious about how they viewed her especially because she's someone who was working in the government within the establishment.

Anastasia Curwood: It's complicated because the classic civil rights era was over, but the Black freedom struggle continued. There are different people integrationists, Black nationalists. There's a whole host of different ideas and different folks within the Black freedom struggle. There's no consensus. There had never been consensus. It just appeared to be-- King was such a powerful symbol and strong figure that he represented the movement, but there's no one civil rights movement.

She is an advocate for the Black freedom struggle, writ large, but she's much more like an Ella Baker say than Martin Luther King in the sense that she is trying to lead by having people discover their own capacities. She's also encouraging young people and youth. She's also not tied to any one organization. She would form alliances. She is in Congress later with Andrew Young, who was leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

In 1972, she actually had some-- a good relationship with the Black Panthers when most of the other Black men in Congress with her, besides Ron Dellums, who was a strong ally, would not talk to or give a hearing to the Black Panthers. She's willing to talk to anybody who feels like they want to participate in her coalition and advance Black people generally. Same with women.

Feminist movement at the time was far from uniform, but because she refused to dedicate herself to one group or come out of one tradition, she's certainly not coming out of this established tradition, then she thought that she would be more available to everybody. Julian Bond was also involved in student non-violent coordinating committee. Really instrumental leader.

He snubbed her and said, "Well, now, we're not going to stand behind Shirley Chisholm. We're going to do a favorite son strategy. He called it a favorite son strategy. That is every local, every state should pick a Black man is usually the term that everybody used to the run that we can all get behind. Then we'll bargain with our delegates, with our Black favorite sons. He really snubbed her. Same with some of the Black Arts Movement folks. Amiri Baraka snubbed her. Jesse Jackson was more supportive. As I said at the beginning, it's complicated.

Alison Stewart: On July 12th, Shirley Chisholm was the first Black person to have her name entered into nomination at a major party convention, the first woman to be nominated at the Democratic National Convention. What happened next?

Anastasia Curwood: What happened next was that she got about 152 votes from the convention floor during the first balloting. Then the ballots got revised and she lost about half of those. She wound up with about a hundred votes in the final tally, and then she conceded. What she'd wanted to have happen was, of course, for people to cast votes for her in the first ballots, enough to tip the balance so that McGovern and Humphrey would have to compromise and would have to listen to her and would need the votes of delegates who were voting for her, but she conceded in a very graceful way.

She pledged her help to George McGovern. George McGovern asked for her help eventually late in the campaign when she couldn't do much. She was a little bit cut out that he did not use her help as much as he could have. She was a good colleague, and she tried to get him elected. It didn't work and he lost in a historic manner.

Alison Stewart: Shirley Chisholm remained in Congress for 10 years after the run. She was on a crusade for expanded definition of minimum wage. Obviously, looking out for domestic workers. We've talked about that quite a bit. When she was at the height of her power in the House Representatives, what did she do with it?

Anastasia Curwood: This is a really important point. She used to make sure that procedure advanced the rights of the people, the rights of the least of us. She did it as a member of the Rules Committee. In some ways, her career in Congress after the presidential run is far more important than has been understood. Is in some ways a more major political contribution. She worked behind the scenes, and so her name's not on a lot of legislation. Her name's on a bill to put up a statue of Mary McLeod Bethune in Lincoln Park, which is a big deal. It's the first statue of a Black woman in the nation's capital. That's important.

She's working in committees and she became a very influential member of committees. She talked to her fellow congressmen and eventually, women lobbied them to bring them around-- educated them about the bills and what was at stake in bills, and tried to get people to vote for policies that would at least preserve the great society, even if it wasn't possible to expand it as she originally hoped.

Then when Reagan got into office and started to cut the budget for the programs that she thought were due the American people, she really fought those. She had this flurry of hearing appearances trying to fight for all sorts of domestic programs from school meals and school funding to funding for the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, all these programs that Reagan sought to slash with his budget. She also made it so that certain bills would get on the floor.

As a member of the Rules Committee, this is the most or one of the most powerful committees in the house. She still stayed in contact with education and labor. She was an unofficial committee member because she would appear at their hearings all the time. Giving could be testimony, but she could say what bills are going to come up and what bills weren't on the floor. When the Congressional Black Caucus rights an alternative budget, she makes sure that that gets on the floor of Congress. Didn't get passed but she really had that influence. The hallways and committee rooms of Congress, it's harder to find what's going on in them.

She told me that she said this to one of her staffers. Her staffer told me that she said this, that if you don't care who gets the credit, you can get a lot done. That was her approach. It's important to understand that her career in Congress after running for president was as impactful as what she did beforehand if not more so.

Alison Stewart: You describe her as feeling free after she left office. She died in January 2005 after being free to retreat from public life. What is something you would like people to remember about Shirley Chisholm and what do you think her legacy is?

Anastasia Curwood: Something that people should know is that later in life she mentored a generation of Black women in politics. She co-founded the National Political Congress of Black women. That was a mentoring organization that included people like Donna Brazile, Maxine Waters, Barbara Lee, of course, who was a really important mentee of hers now is running for Senate in California.

Her mentees both in that organization and on Capitol Hill, her staffers loved her because she gave them free reign to work on issues that they really cared about as long as it aligned with Chisholm's overall philosophy. They could work on whatever issue they wanted, and she really trusted them to do it. There's a whole generation of political workers who owe a lot of their beginning to her, but as far as a larger legacy, I think it's this idea of Black feminist power politics. It's how do you stand up for your ideals and take that into government and electoral politics.

That she's unique in her generation of Black feminists. There are other women who are writers and activists outside of the government, and she took a lot of inspiration from them. She read voraciously and she read their essays, and then she went and incorporated that into government. This is another really important legacy. She's bringing Black feminism to Capitol Hill, but really what I want listeners and readers to understand is that she was a human being.

She didn't magically accomplish these historic firsts that came about as a series of decisions and her temperament and who she was, but she was just a normal human being as well. If you are a normal human being, you can accomplish really heroic and amazing things just as she did. I want people to understand that one needs to be human and needs to be heroic at the same time. It's that legacy of possibility that one human being can accomplish and make a tremendous impact.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics. Anastasia Curwood, thank you for giving us so much time.

Anastasia Curwood: Oh, it's a pleasure. I'm really glad that people are interested in Shirley Chisholm, want to know more about her. Her life is even more fascinating than hers just as a symbol and an icon.

Alison Stewart: Thanks again to Professor Curwood for her time and thanks to WNYC archivist Andy Lanset and the Municipal Archives for finding all that great audio. Shout out to engineer Bill O'Neill and full bio post-production producer Jordan Lauf. Next month in honor of National Poetry Month, we will discuss the Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.