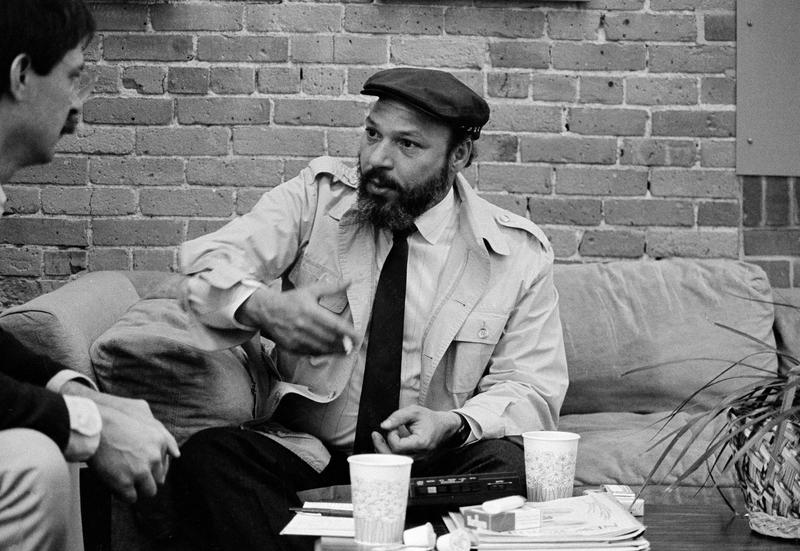

Full Bio: August Wilson (Entire Interview)

( AP Photo/Bob Child )

[intro music]

Alison Stewart: August Wilson's family story begins on Spear Tops Mountain in North Carolina, and we meet the matriarchs, his great-grandmother, Sarah Eller Cutler, and there are a lot of stories about Sarah Eller Cutler on that mountain. What is one that's true and telling about who she was, and what are some of the non-documented legends?

Patti Hartigan: Well, with that period of history, it's very hard to document. When the census-takers showed up at the door, it depended on whose kids were there, who answered the door, who felt like they needed to give a different name, et cetera. The story of Willard Justice being killed up there is absolutely true. That's documented in news, many, many newspapers. The story behind it is what's a little fuzzy. Why was he near her house? Why was he up on the mountain? What were they chasing him for? We don't know, but that scene that I paint at the very beginning of the book actually happened.

Alison Stewart: Her daughter, Zonia, worked as a domestic, and told people that a white man had raped her, and that her children, August Wilson's mother included, Daisy, were the result. Now, Zonia died when August Wilson was five, and he only learned about her through his mom, but he does name a character in Joe Turner's Come and Gone, Zonia. Why would he name a character after a woman that he really had no memory of?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, because he honored all the ancestors. He wrote from what he called the blood's memory. Especially, the matriarchs were very, very important to him. He worshiped his mother, Daisy Wilson. He didn't know Zonia, but she represented the link to the past. There's a Cutler in Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, and he knew that that was a family name. How much of the actual history he knew, I don't think we know that. He never went to Spear, North Carolina. It was a question of, people made the great migration, and they didn't want to go back. They were looking for a better life, but he felt it in his blood. It was kind of uncanny, some of the similarities of the things that I found in his ancestral history and things that appear in the plays.

Alison Stewart: What's another example?

Patti Hartigan: Well, his great-great-grandfather, Calvin Twitty, I found a will of a plantation owner that had a-- It was a Twitty plantation, and there was a Calvin listed in the list of enslaved people. In that same will, the owner left a piano to his daughter, and there's a play called The Piano Lesson. Also, around in Spruce Pines, which is the largest town near Spear, there was a Black man named John Goss who was accused of raping a white woman. It was based on her testimony, her testimony alone. He was working on a chain gang, and in Joe Turner's Come and Gone, as you know, Herald Loomis just got off seven years working on a chain gang.

Alison Stewart: August Wilson's mom, Daisy Wilson, arrives in Pittsburgh in 1937, and she's awed by everything she sees in this area known as the Hill, and the Hill becomes an important character in the life story of August Wilson. Can you describe the Hill and its origins?

Patti Hartigan: Well, the Hill, when August Wilson was growing up there, was a very mixed-race area. It was where he called -- the unwelcome all settled on the Hill. It was a kind of place in the '50s where everybody was an auntie. All the women could yell at any kid if they caught them doing something wrong, and it had a real community feel. There was a watchmaker who lived next door to the Wilsons, there were seven sisters who all stayed in the neighborhood, the Clancy sisters. It was a real community. It had paint stores, and barber shops, and theaters, and it was lively when he was growing up.

Alison Stewart: Daisy had several children, including Frederick August Kittel Jr., born April 27th, 1945. His father was a European pastry chef, is how he's been described sometime, with whom Daisy would have several children. How much did August Wilson, then Frederick August, know about his father?

Patti Hartigan: He was an absent presence in the home. He was not particularly well-regarded. August Wilson looked to a boxer who lived across the street named Charley Burley as sort of a surrogate father. When Frederick Kittel did show up, he was frequently intoxicated, angry, throwing things. The children knew that -- Some of them would hide, and one would run across the street and get Charley Burley. He said in an interview in the New Yorker that he only had one memory of his father. He took him downtown to buy some Gene Autry boots, and the anecdote is that his father told him always to have coins in his pocket, and jiggle them. That was his way of telling August Wilson, "You need to look like you can pay here. You need to be established."

Alison Stewart: I thought it was interesting though that Daisy gave him Frederick August Kittel Jr., knowing that he wouldn't necessarily have access to his father.

Patti Hartigan: Yes. She desperately wanted a boy -- Maybe in those times, everybody named their firstborn son after the biological father. Well, we'll get to it later, but there is a story that she didn't marry him until he was very sick and dying, and she did that because he had another wife. When Kittel's wife died, Daisy said, "Let's get married," and they went to a different courthouse, they didn't go in Pittsburgh. They went to a different county so no one could know, and she was -- According to Richard Kittel, August Wilson's younger brother, she was doing it so they would get benefits when he passed.

Alison Stewart: His mother sounds like a wise woman.

Patti Hartigan: Oh, yes. Oh, my gosh. Yes. [chuckles]

Alison Stewart: My guest is Patti Hartigan. The name of her book is August Wilson: A Life. It is our choice for full bio. Frederick August could read by four. He was a smart kid, high IQ. He had a stutter. How did having a stutter shape his young life?

Patti Hartigan: I think it made him perhaps a little shy and a little defensive. I happened to find someone who went to kindergarten through third or fourth grade with him, and he's the one who told me that he stuttered. There are characters in Wilson plays who have speech impediments, but no one ever knew that it was him in his childhood. I think it made him quiet. If he was called on, he always knew the answer, but he didn't raise his hand. If someone challenged him, he could very quickly get angry, and I think that comes from being a little -- You know, when you have something like that, you might be a little insecure.

Alison Stewart: He experienced some racist bullying in school, especially at Catholic school, and it clearly stayed with him as an adult. What was a story that he would recount of that time over and over again?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, when he went to Central Catholic High School -- You have to understand, this is an elite exam school, and your parish sends you and your parish pays for you. He shows up, and he is a voracious reader. He's read everything, he wants to learn, and there were notes left on his desk every morning using offensive words at recess, and I went to the school and I walked to the same path. At recess, they didn't get to play ball, and they didn't get to do anything. They got in a line and they walked in a circle. As he walked in the circle, someone would step on his shoe, or kick him, or throw a potato chip bag at him, and then pretend that they hadn't done it, and he knew clearly what was going on. He was not welcome there.

Alison Stewart: Even the adults, he was accused of plagiarism at one point. It was a Black teacher who accused him though.

Patti Hartigan: Yes, this is a different school. He left Central Catholic because he just couldn't take it anymore. Then he went to a technical high school where he couldn't get into automotive and they had him making tin cups, and he felt the academics were beneath him. So he went to the final high school, a public high school, and he liked this teacher. He called him Mr. B, and they were assigned to write a paper. August Wilson went and he wrote a 20-page paper on Napoleon. He had footnotes, he typed it himself. When he brought it in, the teacher put it down and said, "You are either getting an A or an E." Now, an E at that time was a failing grade.

August Wilson said, "What do you mean I'm going to get an E?"

Then he said, "Well, who wrote this? You have have older sisters--"

And he said, "I wrote it."

He wouldn't defend himself any further, so the teacher wrote E on it, and August Wilson threw it in the trash basket and left school, hoping for three days that someone would come and find him and apologize to him and make things right. He went and he played basketball on the court outside the school every morning for three days, and no one ever came, so he dropped out.

Alison Stewart: He said, "I dropped out of school, but I did not drop out of life."

Patti Hartigan: Right. He went to the Carnegie Library -- And he hid this from his mother. He didn't tell her he had dropped out of a third school. He went to the Carnegie Library every day, and he read and read and read and read, and he was a complete autodidact. He devoured books. He saw a shelf, which at the time said "Negro Books", I think, and he just read every single one of them. He was so inspired, and at that young age, reading James Baldwin, he said, "You know what? I can do this."

Alison Stewart: Daisy was not pleased when she found out that he had dropped out of school. She was really hard on him. You write in the book, she's described as denying him food, banishing him to the basement. It seems like it took him years to try to make this up to her or to get her approval.

Patti Hartigan: Yes, it did. He said it once in an interview, he had an IQ of 143. He was her great hope. She wanted him to be a lawyer, he wanted to be a poet. Poets don't make money. You can't feed your children with words, you need bread. She was so sorely disappointed in him, and yes, he did always want to make it up to her. When he finally had Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, he said, "Mom, I've got a play. It's going to be -- I'm doing well with this." She said, "You'll be a writer when you're on TV. It wasn't until The Piano Lesson, the film teleplay for Hallmark Hall of Fame was aired, that he was finally on TV. She had passed by that point, but he did look up and say, "Look Ma, I did it."

Alison Stewart: In your chapter, A Period of Reinvention, we begin to see the beginnings of August Wilson as opposed to Frederick August Kittel Jr. When did the name change?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, he changed his name -- He told the story over and over and over again. He changed his name on April 1st, 1965. That was the day that his father passed. He doesn't include that when he tells the story. He had just received $20 from his sister for writing a paper for her, she was a student at Fordham University. He took the $20 and he went down to McFerron's typewriter store and he bought a used Royal Standard typewriter. He carried it back up the Hill because he didn't have any money left, and he put in a piece of -- You remember that onion skin? He put in the paper and he typed all different versions of his name, and he settled on August Wilson, which was a tribute to his mother. He repeated that story, but he never told anyone that was the day that his father passed. I found that at the courthouse in historical records and newspapers. There's something even more poetic about him just changing his name on that day because he had a new typewriter, he was re-christening himself.

Alison Stewart: He also was trying on new personas, perfected some accents occasionally, code-switching between highbrow literary language and street vernacular, wearing tweedy jackets and caps. As a young man, what was he looking for?

Patti Hartigan: I think he wanted to be the next great poet. Really, that's what he was looking for. He read voraciously, he read all the poets. He claimed he didn't read dramatic literature when he decided to become a playwright, but he knew his poetry. He was a great fan of Dylan Thomas. He always had a legal pad and a pen or a pencil with him, and he was always writing. Or if he didn't have that, he was writing on a napkin. He felt in his blood that he was a poet. You see it when he became a playwright, the monologues in his plays just soar like poetry, so he had that training before he started writing plays.

Alison Stewart: How did he make ends meet? People of his age at that time don't often make a living writing poetry.

Patti Hartigan: Right. Well, he didn't. [laughs] People [unintelligible 00:14:33] older than he does to make a living writing poetry, but he had every odd job you could have. In his one-man autobiographical show, How I Learned What I Learned, he intersperses different jobs he had: cutting lawns, washing dishes, short-order cook. He did those jobs to pay the rent, and then when he walked out, he took his apron off, and he put his tweed coat on, and he was a poet.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Patti Hartigan. We're talking about her book August Wilson: A Life, it's our choice for full bio. He always, always, always identified as a Black man, August Wilson did. Even though he could pass, as he had a brother who did, he passed for white. Over the course of his career, interviewers and reviewers would bring up his white lineage, almost as a challenge to his Blackness, and he would get really, really ticked off.

Patti Hartigan: Yes. It wasn't a brother, it was his uncle, Ray.

Alison Stewart: Uncle. Thank you.

Patti Hartigan: Yes, he got angry, and he chose to -- He self-identified. Every human on the planet can choose to identify however they want, but people wouldn't leave him alone about this. He said repeatedly, he talked about Daisy's Kitchen, and that the culture he learned there, the ethics, the values, everything he learned there, the songs, the food, was Black culture, and that's how he chose to identify. There are examples in the book of some really rude people asking him this question and not stopping, even when he clearly said, "This is who I am. Let's move on to the next question."

Alison Stewart: When did he begin writing poetry?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, he wrote poetry in Central Catholic. Actually, he wrote poetry in middle school, because he told a story about leaving poems for a girl he had a crush on in the [unintelligible 00:16:31] school he went to, so he was always writing. But when he left school, he started writing more seriously, and then when he met his fellow poets on the Hill, he really fashioned himself as a poet. He was a poet who worked a day job, but he was still a poet, and he gave readings and -- There's a wonderful video of August Wilson and some of his colleagues going to Oberlin College where they did a reading and they did some activism, and he looks very young. He read all the time.

Alison Stewart: You include one of the poems that he had published about Muhammad Ali. It says;

"Muhammad Ali is a lion

He's a lion that breaks the back of the wind

Who climbs to the end of the rainbow with three steps, and devours the gold

Muhammad Ali with a stomach of gold, whose head is a lion."

Patti Hartigan: Yes. You know, I don't know whether they ever met. Wouldn't that be fascinating if they did? He did meet Hank Aaron. He met a lot of his heroes, .

Alison Stewart: Oh, I'm sure. You write about how August Wilson, things changed for him one day in 1973 when he sat down and wrote what he called his morning statement. It said, "It is the middle of winter, November 21 to be exact. I got up, buckled my shoes, I caught a bus, and went riding into town. I just thought I'd tell you." What was the purpose of this morning statement?

Patti Hartigan: You know, he had been writing this highfalutin poetry. He'd been wearing tweed and adopting a Dylan Thomas accent, and I think this was his way of saying, "This is direct. This is a morning statement. There's no questions in it. Take it on face value, this is what it is, and this is who I am." For him, that was so freeing.

Alison Stewart: August Wilson cited as his influences, the four B's: Bearden, the blues, Baraka, and Borges. Where do we see an example of -- let's start with artist Romare Bearden.

Patti Hartigan: Oh-- The Piano Lesson, the name of the play is taken from a Bearden collage. Bearden lived in Pittsburgh for a while, and some of his collages and paintings depicted the people that August Wilson grew up with. He would look at them -- and I wish I had a copy of The Piano Lesson in front of me-- or even Joe Turner's Come and Gone, there was a man sitting in a boarding house, and he had an abject look on his face. He was broken, he was distraught, and August Wilson said, "What is going on with this man? This man who could be my uncle, who could be the guy who lived next door to me." Then he wrote his masterpiece, Joe Turner's Come and Gone based on what he saw on that image, so Bearden was a remarkable influence. He wrote the introduction for a sweeping biography of Bearden, and he talked about how his whole world changed when he saw these images.

Alison Stewart: As a young man, he became acquainted with the blues, specifically Bessie Smith's, Nobody in Town Can Bake a Sweet Jelly Roll Like Mine. Let's listen.

Patti Hartigan: Ooh.

[MUSIC-Bessie Smith: Nobody in Town Can Make a Sweet Jelly Roll Like Mine]

In a bakery shop today

I heard Miss Mandy Jenkins say

She had the best cake, you see

And they were fresh as fresh could be

And as the people would pass by

You would hear Miss Mandy cry

Nobody in town can bake a sweet jelly roll like mine

Like mine

No other one in town can bake a sweet jelly roll so fine

Alison Stewart: What was it about that song that he would come back to and say, "Yes, this was foundational to my writing?"

Patti Hartigan: Oh, I guess her voice and the way she spoke to him, the sultry, the sexy, it was replete with the culture that he loves in Daisy's Kitchen. He said he played it over and over again 29 times or something like that. Actually, I did interview the woman he was briefly living with at that time, and she said, "Oh, yes he did, and he never played the other side." [laughs] It was a music that spoke to him, and he talked about it later on in his life too. When he was writing King Hedley II which is set in the 1980s, which was a decade he didn't really relate to, he said he was going to listen to hip-hop, he said he was going to listen to rap, and he couldn't do it. He listened to the blues while he was writing the play, and he said because the current generation, the generation of artists in the '80s had learned everything at the foot of the blues.

Alison Stewart: The last two B's are writers: poet Amiri Baraka and Jorge Luis Borges. What was it about Baraka that inspired him?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, he was big in the National Black Arts Movement, and he believed that art and culture could perhaps bring about social progress, and August Wilson and his friends had a theater called Black Horizons, which was modeled after it. I think it was in 1968, The Drama Review put out an issue on Black theater-- I have it. He said he got it and they all read it, and they passed it around, and it was so dog-eared, but they still kept it and they did every one of those plays. Baraka's play, A Black Mass, was in that collection, in that scholarly review, and they did that play with Black Horizons.

Alison Stewart: Finally, George or Jorge Luis Borges, he was an erudite Argentinian writer.

Patti Hartigan: I know, and he always mentioned that, he didn't really talk about it much except for once. His play, Seven Guitars, begins at the end. He didn't start it that way, but he changed it at some point. It begins right after a funeral, and then it goes back in time, and it takes you through the story of how the person died. August Wilson said that he had read a story by Borges in The New Yorker that used that technique of telling you what happens in the very first sentence, and then the mystery is, well, how did it get that way? That intrigued him.

Alison Stewart: Before we wrap up today, I did want to ask about the Black Horizons Theater. You mentioned that. Tell us a little bit about the origin of it and why August Wilson and his friends started it.

Patti Hartigan: That's a really good question. Rob Penny, who was part of the Centre Avenue Poets, was writing plays, and they did believe that the arts could build community and could build confidence and self-confidence. They started this theater, and none of them really knew what they were doing. Nobody wanted to direct, and so they pointed at August Wilson, and he said, "I don't know how to direct," so he went and got a book out of the library. They did these plays, and it was true community theater in the spirit. I mean, it probably cost 50 cents. It was okay to bring your whole family, and kids could run around in the aisles, and they were eager to do these plays written by Black people in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was a formative experience for him, although he really didn't know how to direct. Apparently, when he was directing his first play, he came in, everybody sat down, and he said, "Okay, let's read the play." They read the play, a table read, and the actors looked at him and said, "Well, what do we do now?" He said, "I don't know. Let's read it again."

Alison Stewart: His first play was titled Recycle, correct?

Patti Hartigan: Yes.

Alison Stewart: And it was only performed once?

Patti Hartigan: Yes. It was performed in a park. Maisha Baton, the poet, and August Wilson played in it, and it was a character -- a man and a woman.

Alison Stewart: Why did it only play once?

Patti Hartigan: The audience didn't really take to it very well? [laughs] That summer, they were doing work with kids in the park, and the kids -- when they said, "Well, what do you want to do?" they said, "Let's do Superfly." So, he did his play, and people, they didn't want it. As you said earlier in the last segment, it was a mix of this high poetic language with vernacular, and it went back and forth, and the audience just didn't relate to it. At one point, Wilson ended up smacking the actress and she swore at him, and then the whole audience swore at them, and that was it. That was over. It was never done again.

Alison Stewart: His next big production, Black Bart, or "big" was in 1980. Black Bart and the Sacred Hills. It was a musical. It was a little bit out there. It was also a big failure. What was it about, and what did he learn from the failure?

Patti Hartigan: It was about Black Bart, the old bandit who's in the hills and he's going to turn water into gold. It was a rambling, sprawling western with a multicultural cast of not very finely-tuned characters. He said that he was modeling it after Lysistrata, and so there were some [unintelligible 00:27:01] songs, and the women were dressed like they were in a Bob Fosse show. It was a failure because it was just so out there and wild. On the first night at Penumbra Theater in St. Paul, all the patrons of the theater came, all the people who were making grants, and this is the beginning of the second wave of feminism. Most of the people who ran the foundations were feminist women, and they all walked out on the first night.

Then in a subsequent production, I think a motorcycle went on fire on stage, and so it was a colossal failure. Lou Bellamy, who was the Artistic Director of Penumbra Theater, said, "I will never do a play by that August Wilson ever again," and of course, he went on to do all the plays. When I interviewed August Wilson in early 2005 before he was diagnosed with liver cancer, he was about to turn 60 and about to produce the 10th play, Radio Golf, and I mentioned Black Bart and he started laughing. Just joyous laughter saying, "Oh, that was fun. Maybe I should revisit that." [laughs]

Alison Stewart: Early in August Wilson's career, he didn't have these great successes. He divorced, he's not really seeing his kid as much as he'd like to, he'd moved from Pittsburgh to Minneapolis. From all of your research and having interviewed him, what was behind his perseverance to be a playwright?

Patti Hartigan: It was just dogged. He said he wrote from the blood's memory, but I think poetry and drama flowed through his blood. He was determined. I think maybe partly when you grow up and you're told by the nuns and your mother how smart you are and you're going to be such a roaring success, he just wanted to do this. He fell in love with it. It's that grit, that stick-to-itiveness that no matter what-- He applied to the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center five times. He even sent the same play twice because he didn't think they had read it, and he just kept going. He kept going, and finally he did have the breakthrough with Ma Rainey.

Alison Stewart: That's where we're going next. We're discussing August Wilson: A Life. It is a new biography of the playwright. My guest is Patti Hartigan. This pivotal moment comes in 1982 when he attends the National Playwrights Conference at the Eugene O'Neill Center. Just for context, what is the role of the Eugene O'Neill Center in modern theater? Why would this conference -- what would it offer any young playwright?

Patti Hartigan: Well, at the time that he was there, the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center was known as the launchpad of the American Theater. It was an incubator, a place where playwrights could go in some summers. Usually, they took about 12 playwrights out of however many thousands applied. First, there was a pre-conference where they read the play out loud, and then there was a two-week national playwrights, two or four weeks, and everything focused on the playwright, everything. When Lloyd Richards was the Artistic Director, there was a regular company of actors. They arrived and they didn't even know what roles they were playing. They were told what roles to play.

The directors got the work on stage, but their job was not to hide the flaws. Their job was to let the work be seen as it was and let the playwright figure it out for his or herself, an extraordinary opportunity. I think this was way before places like Sundance were doing the same thing for film, so it truly was just a gift to the playwrights. They had amazing dramaturgs, amazing directors. Everybody lived in community, and it was a theater boot camp for the playwright.

Alison Stewart: As you mentioned, August Wilson applied many times before he was accepted, which brings us to Lloyd Richards. This is where he forms one of the most important relationships of his life with Lloyd Richards, then the Artistic Director of the O'Neill, Dean of the Yale School of Drama since 1979, and an African-American man. At this moment in time, what was Lloyd Richards's reputation in the theater community?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, Lloyd's reputation, he was a Buddha. Everybody looked up to Lloyd. He wasn't a loud man, he walked quietly, but when he said something, he had such gravitas. He had directed Lorraine Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun on Broadway, the first Black man to direct on Broadway in 1959. He had championed the work of Athol Fugard, the South African playwright who wrote about Apartheid. And as you said, he had these three positions. He's also Artistic Director of the Yale Repertory Theater. He truly was dedicated to the playwright and dedicated to the theater. He was the pinnacle, I guess you say, look at those positions that he had. He was a bit of a mystery, that's why people called him Buddha. You would ask him-- you're on the mountain top and you ask Lloyd what it all means, and he would say, "Be where you are."

Alison Stewart: Oh, I like his style already. He would go on to guide the careers of several well-known playwrights: Wendy Wasserstein, Christopher Durang. At this moment, he was championing August Wilson's manuscript, Ma Rainey's Black Bottom during the selection process of hundreds of applicants. Even though, as you write, it was bloated at four hours, heavy with lengthy poetic monologues, but not so precise on the structure of plot. What did Lloyd Richards see in that play and see in August Wilson?

Patti Hartigan: He said, when he read it-- He used to work in a barber shop in Detroit when he was a kid, and he said he could hear the voices of the guys that came in on a Saturday to get their hair cut and just sit around and tell lies. He could hear his people in those voices, and the characters in that play are so richly drawn, that appealed to Lloyd Richards. Now, it needed some surgery, but that's what he was good at. He excelled at that.

Alison Stewart: This is this long collaboration, until problems arose, which we'll talk about in a moment. The New York Times describes this pairing as one of the most successful artistic partnerships in American theater. What works between this playwright and this director, Wilson and Richards?

Patti Hartigan: Well, I think since A Raisin in the Sun, Lloyd Richards was hoping that another playwright would come along, and here walks in this man in the tweed coat and the hat at the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center. For August Wilson, we've talked about his background in writing poetry, but not ever studying dramatic structure. For instance, when he got to the O'Neill, and this was with Fences actually, he didn't realize that he couldn't have a scene end with a guy in the rain, soaking wet, with wet hair and wet clothes, and then at the top of the next scene five seconds later, be in dry clothes and have dry hair. That was something he didn't think about. He just wrote these poetic monologues. To have Lloyd Richards, who knew dramatic structure, he was Dean of the Yale School of Drama, pair up with this raw talent that was oozing out of August Wilson, it was a great partnership. It was great for both men, it was symbiotic.

Alison Stewart: How did they arrive at this idea that they would try out Wilson's work regionally with an eye to Broadway?

Patti Hartigan: That was an idea that Lloyd Richards came up with. The regional theater was started a couple of decades earlier, but he knew these theaters, and it was his idea. It was particularly suited for a writer like Wilson because he didn't like to cut his plays until he saw them. Directors would make him sit in the audience so that he could hear and he could know, "Oh, there's a bad note here, and I got to take that out, and this isn't working." This particular method for him was great. I know it was controversial at the time because the regional theater is nonprofit and it's to bring theater to communities, but the theaters were getting new work by August Wilson. Sometimes the plays weren't ready, they weren't even ready to be on stage at the regional theater, and that's how he learned. It was a rare thing that happened, and Lloyd Richards invented it.

Alison Stewart: We're talking to Patti Hartigan. The name of the book is August Wilson: A Life, it's our choice for full bio. At the Eugene O'Neill Center, there were rules about when plays went up, that they wouldn't necessarily get reviewed, but reviewers could come see them. Is that the way it worked?

Patti Hartigan: Yes, producers and reviewers could come. They usually would come on a Saturday night or a Friday night, but no -- I went there as a journalist and a critic, and I knew the rules, you were not allowed to. You could do a feature, but you could not do a review. Frank Rich was so blown away by what he saw, that the headline looked like it was a feature, but it was really-- there was review material in there about three playwrights, but primarily about August Wilson and Ma Rainey's Black Bottom.

Alison Stewart: How did that review change August Wilson's career trajectory?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, astronomical. When a review like that runs, even if it's a future and not a review, producers see that and they have interest [unintelligible 00:37:30] on seeing, just by seeing something like that. He actually left the O'Neill and he had an offer to turn it into a musical, which he did not want to do. One thing you didn't do was tell August Wilson what to do with his plays. The offer was for $25,000, but the contract said they could fire the writer. He and his wife at the time, Judy Oliver, had recently filed for bankruptcy. He turned the offer down. [chuckles]

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Patti Hartigan: That's what I was saying earlier about his integrity. He really believed it. He wanted control of his work, but that led, of course, to Ma Rainey going to Broadway. After the O'Neill, it was performed at the Yale Repertory Theater, and that production, reviewers were allowed to review there. It was at a professional theater. Then after that, it went to Broadway.

Alison Stewart: August Wilson and Lloyd Richards did five plays together. They had this very fruitful relationship. Things started to fray a little bit because August Wilson began behaving like a director in some cases-

Patti Hartigan: Yes.

Alison Stewart: -but it seems like the real moment that their relationship had a crack that could not be fixed was when Wilson created a production company without Lloyd Richards, or with terms that were sort of insulting to Lloyd Richards.

Patti Hartigan: Yes. Well, there was that. That was the beginning, widening the crack that was already existing because August Wilson didn't feel he was getting compensated fairly for his plays. It was also, he was becoming-- He knew what he was doing. He knew that he was a big name now. He was a bold-faced name. People came to his plays, and he wanted more control. Now, you can't have two directors in the room, so the production company was in a very difficult moment that Benjamin Mordecai and August Wilson formed this company and they really didn't include Lloyd Richards in it.

Then after that, they were working on Seven Guitars, and August Wilson didn't like the way the production was going, and he was insinuating himself in a director's role in many ways in some letters he wrote, some memos, how he acted. Then there was an actor, the great actor, Zakes Mokae was really having trouble in the role of Hedley. August Wilson wanted to fire him, and Lloyd Richards was very loyal to him and he didn't want to. There was a gigantic blowup, and that put the nail in the coffin, shall we say.

Alison Stewart: Because we are New York Public Radio, I have to ask about the time that August Wilson spent in New York at New Dramatists. You note that he arrived and fell in with the-- I think you wrote the ethos of the place. What impact did New Dramatists have on him?

Patti Hartigan: You know, New Dramatists gave him so much confidence. He had arrived as a playwright, they had these residencies for-- it was about seven a year. I think they just closed down if I'm correct, which is so sad-- and he had a place to stay, a place to put his hat. He was a playwright, he had not been on Broadway yet, but this was the recognition that he wanted. He was also a member of the Playwrights' Center in Minneapolis, and he said that when he walked into that room, everyone at the table described themselves as a playwright, and he finally felt, "I'm a playwright now." And the New Dramatists was equally so.

Alison Stewart: When did August Wilson decide that his work was going to be part of a 10-play cycle "documenting the African-American experience"?

Patti Hartigan: You know, it's hard to pinpoint the exact date. Different people have different memories of when it happened. There is a story that he was at a Seder and he heard the first line, "We were slaves in Jerusalem," and it made him think, "We need to remember--" African-Americans need to remember their history, not to hide their history, not to try to move on from their history. It was probably around the time he was working on Joe Turner's Come and Gone, which was the third play, that he realized that he had written this play in the '50s. He had written this play about Ma Rainey at the turn of the century, and why not do one for every decade?

He came up with the idea, and then the idea-- I mean, it's a phenomenal task, and he was finishing this task on his deathbed. No other American playwright has ever done anything this ambitious. There's also a story that one of the playwrights at the O'Neill said that they were walking on the beach headed toward the Crab Shanty to get a sandwich, and Wilson said to him that summer that he had just come up with the idea. So, you can't pinpoint it down exactly, but it was around the time of Joe Turner's Come and Gone.

Alison Stewart: What are the signatures of an August Wilson play?

Patti Hartigan: [laughs] Long monologues. Long poetic monologues. He had something he called a spectacle character, which would be Gabriel in Fences, Hambone in Two Trains Running. They were these seemingly sad sack, down on their luck, disabled, disturbed people who really had the wisdom of the community in everything they did. There's that character, there are the monologues, and the monologues-- You can take a play like King Hedley II, which has some problems with it, I think, but there's a speech that Viola Davis gave about bringing a baby into the world we exist in now. Why would anyone want to bring a baby in if it's going to get shot by a policeman, if it's going to shoot someone, if the child's going to go to jail? I'm tearing up now even as I describe that speech.

[playing a monologue by Viola Davis from King Hedley II]

Viola Davis: I'm 35 years old, don't seem like there's nothing left. I'm through with babies. I ain't raising no more. Ain't raising no grandkids. I'm looking out for Tonya. I ain't raising no kid to have somebody shoot him, to have his friend shoot him, to have the police shoot him. Why you want to bring another life into this world that don't respect life? I don't want to raise no more babies when you got to fight to keep them alive. You take little Buddy Will’s mother up on Bryn Mawr Road, what's she got? A heartache that don't ever go away. She up there now sitting down in the living room, she got to sit down because she can't stand up. She's sitting down trying to figure it out, trying to figure out what happened. One minute her house is full of life, the next minute it's full of death. She was waiting for him to come home, and they bring her a corpse. I ain't going through that. I ain't having this baby, and I ain't got to explain it to nobody.

Patti Hartigan: His monologues spoke directly to the audience, and they're funny even when they're tragic. The play Jitney, the characters on that stage are like the guy next door, the guy Lloyd Richards knew at the barbershop. They tell great stories, if you don't laugh at them, you laugh with them, you can feel them. Those are the things. Then there's also the mystical elements, particularly in Joe Turner's Come and Gone and in The Piano Lesson, there's a feeling that you are going back to the blood's memory. You are going back to slavery. You are remembering those bones walking on the water and Joe Turner, there is a ghost that has to be exorcised in The Piano Lesson.

The final thing is he had his favorite character, and my favorite character, everybody's favorite character, is Aunt Ester, and it's deliberately-- it's E-S-T-E-R, and it's ancestor. She's a woman in each of the plays whose-- her age, supposedly, is the same age as if she had been born in 1619 when the first slave ships came to Jamestown, and she represents historical memory. She is unseen in several of the plays, but she comes on stage in Gem of the Ocean, and she keeps the memory. He said she's just like any 90-year-old woman you see walking down the street who remembers everything that ever happened, and she was the most important character for him.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting that you should mention that character and that Viola Davis monologue, because there was criticism. There have been articles written, and dissertations, and papers, that August Wilson did not write great female characters, or he underwrote female characters. He was often dinged for not having substantial roles for women. One, how aware was he of that criticism?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, I'm sure he was aware of it. The women like that character that I just mentioned, that speech in King Hedley, they got more rounded, there was more to them as he wrote later. He rewrote Jitney. Jitney was originally a one-act play, and the female character of that play is just-- She loves her man, she's going to do whatever he says. In the rewrite, she has spine, and I think that was deliberate. He had his daughter, his first daughter was older now, and he was no longer looking to the 1950s as the paragon of what you write about and how women are perceived in their roles.

I agree with the criticism, especially in the early plays. They are not his strongest point, but even in a play like Fences, Rose is-- She was a 1950s housewife, yet when she learns that her husband Troy has been cheating on her and has a baby by another woman who died in childbirth, she has that phenomenal speech where she says, "This child has a mother, but you're a womanless man." Every single woman in the theater jumps to their feet and starts applauding, so they do have their moments, but I do understand the criticism.

Alison Stewart: We mentioned Viola Davis in King Hedley, of course, people know her in the film Fences. We'll talk about Fences, that's a whole other story which we'll get to, but there were actors who worked with August Wilson again and again and again, the Wilson Warriors. Who were some of the Wilson Warriors?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, the late great Anthony Chisholm, who I interviewed a bunch of times for the book and he passed. He was fabulous. Ruben Santiago-Hudson. There's a whole stable of them. Viola Davis. Theresa Merritt was the original Ma Rainey, but that's the only one she did. The roles are so fantastic for African-American actors, and they always have a sterling cast. James Earl Jones was not a member of the Wilson Warriors, he was in Fences, and that was it.

Alison Stewart: Perhaps August Wilson's most lauded play, it won the Pulitzer, it won the Tony, Fences. There could be a whole dramatic play around Fences and the making of Fences, and all the different characters that intersected with Fences. Let's start with James Earl Jones in the lead. He had a lot to say about the script, and from the reading of your book, it seemed that he and August Wilson disagreed quite a bit.

Patti Hartigan: They did. James Earl Jones was pretty direct and he said he didn't like August Wilson and he said that August Wilson didn't like him either. James Earl Jones did want to make some changes to the play. He had a lot of opinions and he wasn't shy about sharing them.

Alison Stewart: Was this unusual behavior on James Earl Jones's part for an actor of his stature at that time?

Patti Hartigan: I don't know. I think in any production, everybody has a lot of opinions, but August Wilson was adamant and this was a real turning point for him, that he had final control over his work. James Earl Jones and the producer had different ideas. August Wilson was a very stubborn man, and when he didn't want to do something, he wasn't going to do it. He was going to stick to his guns. It was a very volatile pre-Broadway run, shall we say, in San Francisco.

Alison Stewart: It wasn't a secret. That's something I found interesting. It seemed like everyone knew that the playwright and the actor did not get along.

Patti Hartigan: People within the production knew, but people from the theater who I've known for several decades had sort of heard rumblings about this story, but never knew what parts of it were true and what weren't. Within the production, sure they knew, and when there were moments where there was a lot of anger and some yelling and they fired Lloyd Richards briefly. Who fired Lloyd Richards? They fought about the ending. Within the production, yes, you couldn't not know, but in the outside world, it won the Tony Award, it won the Pulitzer Prize. Everybody applauded and it got standing ovations and it was his most financially successful play.

Alison Stewart: It was a play that it took decades, passed Wilson's death to get to screen and it's a really interesting reason why. Please correct me if I'm getting these facts wrong, Eddie Murphy got the right to Fences.

Patti Hartigan: He optioned the rights, yes.

Alison Stewart: August Wilson was really demanding that there be a black director.

Patti Hartigan: Yes.

Alison Stewart: That seemed to be the hurdle to getting Fences made, one of the hurdles. Explain what happened.

Patti Hartigan: He said that at his first meeting at Eddie Murphy's mansion. Remember Eddie Murphy, he was at the top of his game at this time.

Alison Stewart: This is 1987.

Patti Hartigan: Yes, and in high, high demand. August Wilson just said, "I want a black director," and then they had a back and forth where I think according to Wilson in a PC they'd wrote, Eddie Murphy said, "I don't want to hire someone just because they're black" and August Wilson said, "Neither do I." I want to hire somebody who's good, who's going to do the film. He said that and he couldn't get it. He didn't like some of the people they were offering him. They were offering him white directors and he just said no, if it gets made, it gets made; if it doesn't, it doesn't.

He felt very strongly about this one in particular because more people were going to see the film version of Fences that had seen all of his plays probably, and so he felt very strongly about him.

Alison Stewart: That was a question I had, is that this is a play that so many people could see, yet he was so adamant about having a black director. Why was that more important to him and to his legacy than getting this story to a large amount of people? Did you get a sense of why?

Patti Hartigan: He wrote about it. He wrote a piece in Spin Magazine, and then it was excerpted on The New York Times op-ed page and there was an uproar about it. For this particular movie, he felt that in order to direct it, you had to be a member of the culture that it depicted. He felt very strongly about that and that's why he kept saying no. When he didn't want to do something, he didn't do something, and when he made up his mind about something, he stuck to his guns. It was really important to him. Then you wait and what is it? 2016 from 1987 and you need someone with the wattage of Denzel Washington to finally be able to direct the film and get it off the ground.

Alison Stewart: What were other instances when August Wilson did allow his work to be televised or to be reconsidered for screen?

Patti Hartigan: The only other one was the teleplay of The Piano Lesson which was a Hallmark Hall of Fame television film.

Alison Stewart: How involved was he in the making of that?

Patti Hartigan: Very. I think he has a credit as a producer on that. It was filmed in Pittsburgh in 1994.

Alison Stewart: Did he consider that a professional success?

Patti Hartigan: He never really talked much about it. I'm sure when it aired, there were millions of people watching it again more than had seen his plays. He did feel great because

he was finally on television and he could speak up to his mother in the heavens and say, "I did it, Ma." You can find it. There's a really grainy version of it on YouTube. I don't know, it's probably. It's very much by the book. He didn't really talk about that actually to tell you the truth. I think as he got closer to the end of the cycle, the goal was to get those plays on paper because he said he was writing 10 and he was going to write 10, and that hung over his head a lot. There were so many other things he wanted to do.

He had the beginnings of a novel. Wouldn't you love to read an August Wilson's novel? He talked a lot and laughed a lot about a play he called The Coffin Maker play which had all crazy cast of characters like [unintelligible 00:56:55] including Queen Victoria and the guys, the coffin makers were fighting with the undertakers and they were all on strike and that was the premise for the play. That's all I know. I haven't read any more of it. I've seen some notes. I think rather than focus on the film medium, he really wanted to finish the cycle and it can get an impediment. It can get in the way if you're thinking about Hollywood.

He also felt and he said many many times, he was offered screenwriting opportunities by major directors. He turned them all down because he knew too much about playwrights who had gone to Hollywood and then they never wrote another play.

Alison Stewart: Wasn't he offered to write about Amistad?

Patti Hartigan: Yes. According to his attorney, yes.

Alison Stewart: Let me ask you about his attorney. That's quite a nice segue.

Patti Hartigan: Oh.

Alison Stewart: John, is it Breglio?

Patti Hartigan: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Who was and still is a powerful entertainment lawyer and producer. Why did someone like August Wilson need a John Breglio in his life?

Patti Hartigan: After the non-review ran in The New York Times after the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center production of Ma Rainey, he started getting all these offers. He had two different agents. One of them he was furious when he got that offer to turn Ma Rainey into a musical and he wasn't having much luck with agents. It was actually Benjamin Mordecai and Lloyd Richards who introduced him to his attorney because he needed somebody, but he didn't want an agent anymore.

John Breglio became really quite protective of August Wilson serving like an agent but also serving for contracts and things like that, anything legal, and that's how he got it. Again, it was August Wilson saying, "I don't like agents and I'm not doing it the way everybody else does it.

Alison Stewart: We're discussing August Wilson: A Life. It's our choice for Full Bio. My guest is Patti Hartigan. At the height of his success in the '80s, it's the late '80s, he's got that fat one run where he is got Fences on Broadway and Joe Turner's at regional theaters, The Piano Lesson is going to debut at Yale, who were his friends? Who was around him at this time? Who were his peers?

Patti Hartigan: The late '80s. The late Claude Purdy was a director who had worked all over Europe. He moved to St. Paul when Penumbra Theatre was founded and he convinced August Wilson to move to join him there. "This new theater, it's all about us." Those two were tight during that period. The poets back home in Pittsburgh, he was still very tight with them, but he was living somewhere else. He was hearing the voices of Pittsburgh, but he was living in St. Paul. He always had a group of male friends.

Later when he moved to Seattle, the great novelist Charles Johnson was his dear friend, but how much time did he have? He didn't actually go to parties. He would go on vacation. He was really just directed.

Alison Stewart: Yes, it's interesting as we've been talking about his career, we've talked very little about his family or his personal life. On his gravestone, it says "Playwright and poet above father and husband and family member." There's this 60-minute interview he did with Ed Bradley, and they seem very comfortable, and at the end, he says, "Yes, the work comes first, family comes second."

Patti Hartigan: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Did you find that to be the case in your research?

Patti Hartigan: I did find that to be the case. He truly cared about and truly wanted to be more involved with particularly his children, but again, the work came first. It's a price someone like that pays. In my prologue, I tried to create a cinematic scene of him at the height of his career, but near the end and looking back in his hometown of Pittsburgh that he had done all these things he said he was going to do, but what did it cost him? I think family might have been a little bit about that. I also have heard stories from people being interviewed of him answering the door in a birthday hat, those pointy hats because it was his daughter Azula's third birthday.

I think maybe his wife at the time had left to go get the cake or something and he was stuck with 15 three-year-olds. [laughter] He's like, "Come on in, we're having a party here." Yes, it's a rough thing. It's a rough thing for any artist who makes that kind of choice, especially because he set the bar so high for himself, but yes, he would admit absolutely that the work came first.

Alison Stewart: Just so we're clear, would you run through his marriages and his children? I feel like we should say their names out loud.

Patti Hartigan: Yes, sure. His first wife was Brenda Burton. They were very young. They were in Pittsburgh and they had Sakina Ansari Wilson was their daughter who was born around 1970, was it '70? That ended because they had actually been evicted from their public housing and she filed for divorce. He was working all those odd jobs and working at the theater until late at night and poetry wasn't paying the rent. She went on to nursing school after that. When he moved to St. Paul, he met Judy Oliver, who was a white social worker. They were married for many years and she was his muse.

She wrote the grants. She sent the grants off and they split up in 1990. Then his third wife is Constanza Romero. They married in 1994, but they were living in Seattle together before that and they have one daughter, Azula Carmen.

Alison Stewart: Do his children carry on his legacy, the mantle of August Wilson, "my dad the playwright," or is he just Dad?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, that's an interesting question. I think for Sakina, she's older. I think it's a little of both. Dad first. He's definitely Dad first, but they honor the work. Yes, sure and the legacy is so important.

Alison Stewart: August Wilson gave a famous speech they delivered at a Theater Communications Group conference in Princeton, New Jersey in 1996. It's called The Ground on which I Stand Speech. Patti, he said the quiet part out loud, that Black playwrights and theaters are underfunded and underappreciated and under-considered, and that colorblind casting was an insult because the Black experience mattered. How did he, or we'll talk a little bit more about the speech and the response to the speech, but how did he end up giving this speech in the first place?

Patti Hartigan: Theater Communications has this annual conference, which is a gathering of who's who of regional theater in some commercial theater too. That year things were bubbling. There was talk in the theater community about lack of equity and who's on stage and something needed to be done. The director of TCG at the time hired Ken Brecker and his wife to plan this conference. Out of the blue, they thought "You know who's got a lot to say? August Wilson." They asked him to do the speech and he said no.

He was in Pittsburgh at the time working on Jitney and he thought about it, he said, "You know what? I'm going to do the speech." They knew that they were going to get something fiery. They didn't quite know how fiery it would be.

Alison Stewart: Here's one of the things he said. "There are and have always been two distinct and parallel traditions in Black art. That is art that is conceived and designed to entertain white society, an art that feeds the spirit and celebrates the life of Black America by designing its strategies for survival and prosperity." What happened after he gave the speech?

Patti Hartigan: You mean immediately in the aftermath?

Alison Stewart: Let's talk immediately in the aftermath.

Patti Hartigan: Immediately it created a buzz. There was applause. There was applause, but there was also shock. People walked out, some people. Some of the head honchos of these regional theaters saying, "We've been trying to do something to make things more equitable and we've been doing everything wrong." That was the response. There was also anger. There were also actors who had fought long and hard for non-traditional casting or colorblind casting and they disagreed with him. At the conference itself, the whole thing came to a halt and they had meetings outside impromptu.

No one cared anymore about the panels on how to make a better box office. They all wanted to talk about the speech, which was great, right? More talk about these issues is fabulous.

Alison Stewart: One of the points that he was trying to make, which I thought was very interesting was the idea that Black culture is culture and that seems very like, duh, right? Then 2023, [laughter] but at this time, what were some of the things that he was writing about that might really be foreign to predominantly white audiences?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, that's such an interesting question in retrospect. There was one time at the Huntington Theater. I think they were doing the piano lesson. I was talking to Lloyd Richards and he said that a couple had come on one of the previews, walking out of the theater they recognized him and they went up to him and they said, "Mr. Richards, thank you for inviting me into a Black family's home. I've never been invited before."

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Patti Hartigan: Yes. I can't tell it with the same gravitas that Lloyd Richards told it, but I think maybe that was true for a lot of people. You certainly weren't seeing it on stage, so yes. It is funny that you read that now and you think he actually had to say that, but it was in "controversial".

Alison Stewart: Yes, it was controversial. That was what was so interesting about it. There is a very well-known theater critic for the New Republic, Robert Brustein, who also has an incredible resume, which I'll get you to tell us a little bit about, who wrote disparagingly of August Wilson's work. Then we're going to trade carefully because Mr. Brustein just passed away, but we do need to get into what the two men talked about. Just for context, could you explain who Robert Brustein was and his role in theater?

Patti Hartigan: Robert Brustein was, in addition to being the drama critic at the New Republic, he was the dean of the Yale School of Drama and he founded Yale Repertory Theater. He was replaced by Lloyd Richards. Brustein's contract was not renewed by, I think it was A Bartlett Giamatti was the president of Yale at the time. He ran off with his actors and went to Cambridge and had a collaboration with Harvard and founded the American Repertory Theater. The American Repertory Theater during Brustein's era was known for auteur directors doing their interpretations of classics. It was heady and exciting, it was different. When he left Yale, he made some comments about how the Yale School of Drama was going to be all about undergraduates and the graduate students. You wouldn't have another Meryl Streep, which was really a stab at Lloyd Richards who had just been hired to do the job. Lloyd Richards never said a word publicly. He was very quiet. Then Robert Brustein wrote he did not review the first few August Wilson plays on Broadway, but he did review the piano lesson. This was a review, I think it was in the days before we could email it back to each other, but everybody in the theater world had a copy of this review because it was scathing.

He used incendiary language that was insulting and demeaning and that began. Then when Wilson gave his speech, Brustein fired back at The New Republic, and then it went back and forth, and they had the answering each other with essays in American Theatre magazine as well. Then the two of them met at town hall in New York for what was billed as the fight of the century. It really wasn't, but I was there.

Alison Stewart: Oh, okay. I can't wait to get to that. Two things about Brustein's criticism of The Piano Lesson and of August Wilson. What were his main criticisms, first of all?

Patti Hartigan: He didn't like the play. That the play was kitchen sink propaganda. He also didn't like the way the plays were being produced at regional theaters before going to Broadway. I think he called it Mick Theatre. That he was an early founder of regional theaters in the country and he felt that non-profits should be non-profit, even though his theater, American Repertory Theater, had set a couple of plays to Broadway.

Alison Stewart: When you say kitchen sink, what does that mean?

Patti Hartigan: Traditional, nothing experimental. Kitchen sink I mean well-made. I'm not going to use the language that he used in the review because I don't want to, but just very traditional, very conservative. Story takes place, one set, family. That was his criticism. He didn't think he was covering any new ground.

Alison Stewart: Because the language he used, it would not be acceptable today. That review would not be published today.

Patti Hartigan: I hope not. [laughter] You can say just the way he phrased things was just really deliberately goading. I will say that Robert Brustein did a lot of great work at the American Repertory Theater. I have to say that to the recipe since he did pass and he was an experimental great mind of the theater. He had fights with people.

Alison Stewart: If you can read the New York Times obituary of him, it's very even-handed and it does say that while he was a great lion of theater, there were many people who had fights with him.

Patti Hartigan: Oh, yes. I'm in the index of one of his books. He didn't like me for a while.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: August Wilson said of Brustein's suggestion that people might be producing plays by marginalized groups like filling quotas basically. Wilson said, "Brustein's surprisingly sophomoric assumption that this tremendous outpouring of work by minority artists leads to confusing standards and that funding agencies have started substituting sociological for aesthetic criteria, leaving aside notions like quality and excellence, shows him to be the victim of 19th-century thinking in the linguistic environment that posits Blacks as unqualified.

Quite possibly, this tremendous outpouring of works by minority artists may lead to a raising of standards and a raising of levels of excellence, but Mr. Brustein cannot allow that possibility." Did these two men really not like each other or was this about two public intellectual sparring?

Patti Hartigan: It became about two public intellectual sparring. When they had their showdown, which wasn't really much of a showdown at town hall, the great Anna Deavere Smith was called in to moderate, but it was seriously being built like a boxing match. People were taking bets. It was a star-studded audience, it was a freezing cold night, and neither one of them wanted to do it, but they couldn't say no. According to Brustein, they did make-up and got to be friendly. I certainly didn't get a feeling that August Wilson was holding any major grudge against Brustein near the end. The questions from the audience were absurd. [laughs]

I think Brustein at the end said something like, "Oh, the thing I've learned about you is that you're a teddy bear." He said it to August Wilson. The minute he said it, he felt like an idiot because it's a stupid line. Wilson came back and said, "I may be soft-spoken, but I assure you I'm a lion." It was really for show. What Anna Deavere Smith had hoped to do was to have a conversation like the conversation that Margaret Mead had with James Baldwin. To really intelligently talk about issues, agreeing to disagree, but really getting a substantive. It was just billed as the event of the year.

Alison Stewart: I'm going to play a little bit of the middle of this, NPR's Fresh Air has audio of the event, where they did get into it a little bit, each presenting their side. You could hear the audience reacting. We'll take a listen.

Robert Brustein: I think you have probably the best mind of the 17th-century. You're describing as a 17th-century condition, August. You're not describing a 20th-century condition. You speak of most Blacks being locked out of the house. That continues to be true, but it is not as true as it was in the 17th-century. You speak of people being brought to this country in chains. He speaks of Black people being brought to this country in chains, and that is the original sin of this nation, which, like all original sin, will probably never be expiated. This country is trying to expiate it. The fact is that to declare that you have African blood in your veins 300 years after you left Africa.

Alison Stewart: Let's listen to a little bit of August Wilson's argument.

August Wilson: I find that this is some of the most outrageous things I've ever heard.

Anna Deavere Smith: What just now--

Robert Brustein: Can I finish?

Anna Deavere Smith: Jump in, please.

August Wilson: I can understand.

Robert Brustein: I'm saying that in the same way that Lorraine Hansberry said that in A Raisin in the Sun.

August Wilson: You are aware that in the 17th-century, we were slaves, Blacks in America were slaves. You're aware of that.

Robert Brustein: Of course, I'm aware of that.

Alison Stewart: Patti, did anything come of this brouhaha? Did anything change?

Patti Hartigan: [chuckles] That's a really interesting question. I have to go back to 1991. I get into this in my afterword in my book. When my colleague Diane Lewis and I wrote a series called The Fine Arts World Without Color for the Boston Globe, and it was a four-day page one series with all the Boston institutions, all the national institutions, looking at staffs and boards and what's on stage, what's on the walls, who's in the box office, et cetera, the art world in this country. At the time in 1991, half of the people said, "How dare you? How dare you take home the fine arts? We have no obligation to do this." Some of the people said, "Oh, thank you for saying this."

You fast forward to 1997 when August Wilson has this speech and the debate in New York. Afterwards, he was interviewed time and again. There was a Charlie Rose interview where Charlie Rose said, "Look, you have George Wolfe at the Public Theater, you have Kenny Leon at the Alliance Theater in Atlanta." August Wilson said, "You know what? Nothing has changed. Just because you have two people leading two theaters, the only people I see at these theaters I go to around the country who are people of color are the janitor staff."

Then fast forward to a pandemic and George Floyd and the aftermath of that and now all arts institutions, you can go to any website, right on their homepage, there's a diversity initiative. I hope they're genuine and I hope there really is change, but August Wilson would have told you on the day he died that he hadn't seen any change.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Patti Hartigan. We're discussing her book, August Wilson: A Life. It's our choice for Full Bio. In the last decade of his life, he was writing his final play, Radio Golf which was produced on Broadway after his death. Gosh, he died just months after he was diagnosed with liver cancer, right?

Patti Hartigan: Yes.

Alison Stewart: He was young. He was only 60. From your research, did he have any unfinished business personally or professionally? Aside from Radio Golf going to Broadway, were there other things that he wanted to do that he didn't get to do?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, there were so many things. I told you he had that novel that he talked about. I don't know how many pages he had, but he had started writing the novel. He had that comedy. It's funny that he said late in his life that he wouldn't mind writing some screenplays, but he didn't want them to have anything to do with issues of race. He wanted to write comedies, he wanted to lighten up. He had actually taken up painting. When I interviewed him in 2005, it was a few months before he was diagnosed, he said that he had read some article that said that painters live longer than writers, [chuckles] then said, "I'm taking up paint."

I think he wanted to work in another medium. he had written those 10 plays, phenomenal output, phenomenal change in the American theater. The legacy is extraordinary, but yes, he wanted to kick back a little bit. He said that he would never write the words "the end" at the end of a play unless he had either an image or a first sentence or a scene or an idea for the next project. He already had so many projects he had been planning.

Alison Stewart: There are so many people that are mentioned in the book that we didn't get a chance to talk about. Amy Saltz, the director, Todd Kreidler, who worked with him on his one-man play. Is there any person that we haven't mentioned that you think is important when we're thinking about the life of August Wilson?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, yes. You know what? I will say a word about Marion McClinton. I mentioned Claude Purdy, who was August Wilson's friend, but he did not choose him to replace Lloyd Richards when he split with Lloyd Richards. He tapped Marion McClinton, who was also from St. Paul, playwright actor. He had been in the original Jitney, the one-act production that Penumbra did in 1980. Those two were very tight. Yes, he directed the last few plays, and then he got sick and he had to drop out of Gem of the Ocean. It was complicated. Todd Kreidler was also really, really, really significant in his life.

He adopted him as a surrogate son and the two of them were volatile and they would fight with each other, but they did it with love. Todd became his dramaturg. Of course, I did mention Charles Johnson, who he had a really close relationship and felt Charles Johnson welcomed him to the City of Seattle. They would go out for these late-night dinners that rolled on and on from you start with an appetizer, and then the next thing you know, it's three o'clock in the morning. Charles Johnson wrote a great essay about it in a collection called Night Hawks.

Alison Stewart: In your author's note, you write, "I first met August Wilson at the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center in 1987, and the descriptions of the O'Neill are from my direct experience as a fellow in the National Critics Institute and numerous visits to the O'Neill over the years. I also interviewed Wilson many times as a critic and arts reporter for the Boston Globe. I spent several days interviewing him in Seattle in January 2005 for a Boston Globe Magazine profile, one man, 10 plays, a hundred years. The wide-ranging interviews covered his entire life. Many of the quotations in this book are drawn from those interviews, as is the opening scene in Chapter 19.

Many of Wilson's intimate letters and early plays in poetry are paraphrased because August Wilson's estate declined authorization of this book. I hope readers will get a sense of his eloquence nonetheless." Did you get a sense of why they declined to be authorization of the book?

Patti Hartigan: That was a conversation. There were a bunch of lawyers in rooms in New York and agents. It didn't work out. I think there was a little more control wanted than a journalist can give.

Alison Stewart: Understood.

Patti Hartigan: That's really all. I don't have anything negative to say. I did the best I could with what I had. Does it make it harder? Does it make you work harder? Absolutely, but the people in the August Wilson world, in his universe were amazing and fabulous, and the libraries were terrific. A lot of people keep a lot of things you learn when you start digging into somebody's life.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: What is the legacy of August Wilson?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, he changed the American theater. Don't you agree? He opened it up in a way that it should have been opened up before, but had not been. He wrote a great play, 10 great plays that also chronicled the Black experience. He changed the theater, but he wrote a record of stories and the characters in his plays are not superheroes. They're regular people who did extraordinary things. I think those two things are the legacy, what he did for the theater and the work that he left behind.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is August Wilson: A Life. My guest has been Patti Hartigan. Patti, thank you for giving us so much time.

Patti Hartigan: Oh, thank you for doing this. This program is terrific and all writers are grateful.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.