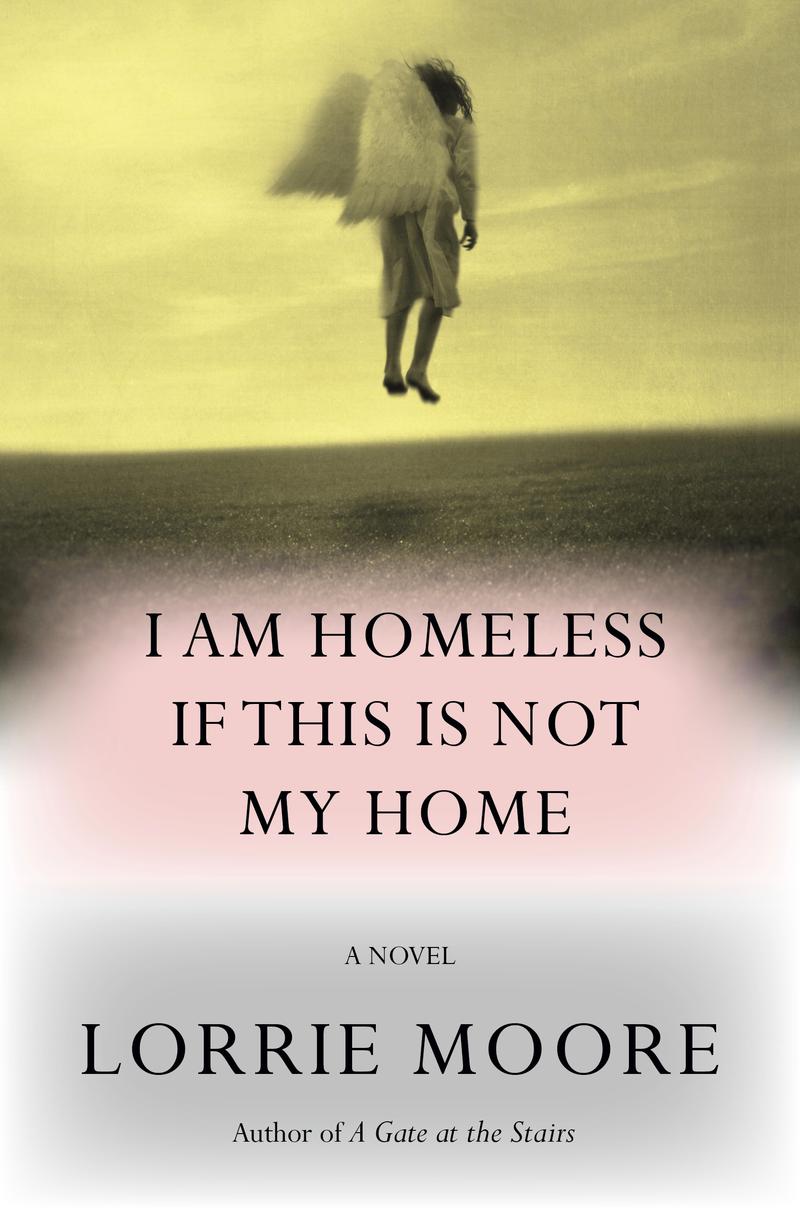

The First Lorrie Moore in Over a Decade

( Courtesy of Penguin Random House )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. Whether you're listening on the radio, live streaming, or On Demand, I'm grateful you're here. On today's show, we'll kick off this month's full bio conversation about Martin Luther King Jr. We'll be joined by Jonathan Eig, author of King: A Life. We'll continue our Pride Month series on banned and challenged books with Mike Curato, author of Flamer and drummer Kassa Overall, joins us for a listening party for his new album Animals. That's the plan, so let's get this started with author, Lorrie Moore.

[music]

Listeners, we just want you to be aware that this next conversation will contain mentions of suicide. If at any time you need support, please text or call 988. That's the number for the national suicide and crisis lifeline. It is open 24 hours a day. Writer Lori Moore's trademark combination of humor and heartbreak has earned her a loyal following, one that's been waiting for more than a decade for a new novel, it has arrived. The genre-defying, I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home is made up of two stories running in tandem.

In one we meet Finn, a recently booted history teacher with a soft spot for conspiracies. His older brother is dying of cancer. When he hears that his former girlfriend Lily has died by suicide, he goes to visit her grave and ends up encountering a version of Lily who can walk and talk and yet times looks and smells quite dead. What to do with your possibly ghosts like ex-girlfriend? Take a road trip.

The story is intertwined with journal entries from a woman running a boarding house in the 1800s. She becomes convinced that her handsome but racist border who says he comes from a family of Shakespearean actors and claims his name is Jack, might not be exactly who he says he is. In his review of the novel, Kirkus says it doesn't get more elegiac than this. New Yorkers can catch Lorrie Moore in a variety of events. Tonight at 7:30 PM, she'll be at the 92nd Street Y. Tomorrow at 7:00 PM, she'll be at Books are Magic, our friends, and on Thursday, she'll be at Symphony Space in conversation with Meg Wolitzer. She joins us now. Hi, Lorrie.

Lorrie Moore: Hi. Thank you for having me.

Alison Stewart: This book involves death, involves dying, maybe what happens right after you die, the in-between space. When did you decide death was something you wanted to tackle in a novel?

Lorrie Moore: Perhaps when a lot of people I knew were dying. You get to a certain age and you start to know more people who have passed away than who haven't. I think all writers are a little focused on death. It is the big theme in life and literature.

Alison Stewart: There are so many different ways that different cultures think about the afterlife. Whether or not you are from a culture that you take things with you when you are buried so that you'll have them to use in the next stage. What kind of research did you do about afterlife in different cultures approaches to afterlife?

Lorrie Moore: Actually, I didn't do that much research regarding the afterlife as it's conceived of in other cultures and religions. I did do some research regarding this "afterlife of John Wilkes Booth" because there were many, many sightings of him after he was ostensibly killed, and sightings all around the world and people claiming to be him. Other people claiming to have his dead body and all these things. I thought well, the confederacy was trying to hang on and rise again or there was a form of resurrection of it in this almost carnivalesque idea of John Wilkes Booth. I thought of it in conjunction with the year 2016 when Trump was elected and the Confederacy, certainly helped with that. Mostly I was trying to make my way through one particular character's love of someone who has died and I kind of made up what I thought he would experience.

Alison Stewart: One of the reasons Lily seems ready to go and hop in a car and go with him, even though she's dead she had a green burial. I thought this was interesting, a way of burying the dead so that they decompose naturally as opposed to being embalmed. People are buried right away. Where did you first become aware of green burials?

Lorrie Moore: Well, I think I knew of them because I had a friend who was always talking about wanting to be buried in this green cemetery that was in Wisconsin, actually. Then he did die and he was buried there. [laughs] I shouldn't laugh, why am I laughing? It's a little bit like a Jewish burial, I think. Jewish cemeteries work that way, I think as well, where you're not embalmed, you have to put the body in the ground very fast. To some extent, it's also a climate change novel, because she's buried when the ground is slightly frozen. Then there's a kind of thaw and then suddenly she appears. There's that theme as well.

Alison Stewart: I thought it was such a smart idea because she has to be buried so quickly, so she's not that dead. Maybe she could come back. Same as maybe it could happen.

Lorrie Moore: Well, George Washington used to be afraid of being buried too soon. He said, "Wait five days." He was absolutely insistent because he felt somehow. Apparently, there have been proven cases of people who were buried too soon. There were-

Alison Stewart: Claw marks

Lorrie Moore: -claw marks on the coffin lid and things like that. It's all rather gruesome, but with a green burial presumably, especially if there's a thaw, you could get out, I guess. This was my imagination of what could possibly be Finn's experience with his suicidal, but beloved ex-girlfriend.

Alison Stewart: Do you think of this as a ghost story in any way?

Lorrie Moore: I do. Some people are calling it a zombie story, and it's probably that too. It can be any number of things. I don't really care that much about what it's called. I also think it's a love story. I think it's also a conversation with the past, and it's about that, how we have these long conversations with the past. Whatever you call it, is fine with me. I realize it's a little bit genre-bending, and making up its own genre, and its own structure, but novels do that.

There's not an actual set form for a novel, not even the way there isn't a short story where at least you have length, forming, what a short story can be. A novel can be short, it can be long. It really has no formal requirements so you're making up the whole structure, and you can make up the whole genre. I think that's what I did here. Which is why some people are having trouble with it but if you stick with it, I think it becomes clear as an experience for the reader. Yes.

Alison Stewart: When did you come to that? It's such an interesting way to describe a novel is not really having to have any particular rules, except that I guess it's fiction. When did you come to realize that?

Lorrie Moore: That a novel has no--

Alison Stewart: The way you just described it as it can be any length, it can be any subject, just as long as it's fiction, I suppose.

Lorrie Moore: Well, I remember reading an essay by William Gass, who said the novel has no organic form. I thought, yes, that's right. I've repeated that in other essays that I've written about novels. That there is no form. The author has to really make it up. Whereas I suppose if you're writing strictly genre fiction, or if you're writing formal poetry, and even with short stories, you can't go past page 50 or it's no longer a short story. There are limitations in other genres, and other forms but with novels, you can make up whatever you want.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Lorrie Moore. The name of the new book is I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home. Lorrie is speaking tonight at the 92nd Street Y, tomorrow's is at Books are Magic and Thursday at Symphony Space. She's going to be in our area for a little bit. You're going to be in New York?

Lorrie Moore: Yes.

Alison Stewart: I would love to have you read your description of New York from your book, I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home.

Lorrie Moore: Okay. This is where the more contemporary part of the novel begins. It begins with this, Korean griddle grease and the smoke from late morning weed in the air whites, excuse me, winds, light and variable, the sweet stink of sun-warm trash bags. This was the Indian summer the Algonquin had wanted to be rid of and succeeded absconding with their jewels and hilarity, the vibrating scorch and scotch of the subway, the sulfurous sewage exhaled from the hard open mouth of the Broadway local, block after block of brick and concrete buildings, some roaring, some asleep and caged in geometric jungles of scaffolding. Traffic rumbled like a sea. Ambulances practiced their glissandos. Authority was the merchandise as well as the port. "Authority" was everybody's brand. Vespas sped by seemingly without riders. Finn got the young attendant to retrieve the car from the garage early from the early bird special. While waiting, he noted a bicycle Rick Shaw slowing in front of him.

Its driver resembled Pete Seeger replete with a neat wool cap, a flannel shirt, suspenders. Instead of crooning turn, turn, turn, he was screaming, watch, watch, watch at the top of his lungs. Watch out for the instructions under the hood. Don't think they're not there. Be afraid of the silver ladies and the pink wires and the shoes, the shoes, the shoes. The white schizophrenics were allowed to ride bikes here. The Black schizophrenics huddled under blankets and cardboard on sidewalks against the facades of the skyscrapers. Pieces of paper rolled into jars with scrawled writing faced outward, I am not homeless. This is my home. "Hey," the man running the food cart on the corner of 28th shouted at the Pete Seeger bike cabbie, "Dude, you need a burrito." Then the bike cabbie drove away.

The Chelsea cookware bombs had happened one month before. People were both moving on and not. The smell of the city in mourning, the mix of food and smog triggered in Finn the trips to strange cities he had taken as a child. He had been made to be up too early with his school groups or his family and now he could feel again the vague terror and strange adventure of a world happening simultaneously and separately from the world he was from. Cities seemed cobbled together from parts of other cities in other times.

Alison Stewart: That was Lorrie Moore reading from her book, I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home. We heard a little bit about that in the passage. How did that become the title for the novel?

Lorrie Moore: Oh, it was my working title. I thought it was like a blue song. I meant it to be about people, not people who don't know where they live necessarily, but people who are not necessarily at home and at ease in the world. That's certainly some of the characters here especially Lily and probably Finn too where there is just uneasiness which is translated in psychological terms into a kind of existential homelessness. I imagined it as the title of a blue song I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home. I could totally see it.

When I got to the end of the book-- Sometimes when you're working on something, you have a working title, and the novel when it's done has moved slightly to one side of the title but I still wanted to keep it so I had to fight for it a little bit because my editor thought it was too long. She said, "I let you have who will run the frog hospital. I don't know about this one." But we worked it out.

Alison Stewart: I want to mention Finn and Max's relationship. Max's brother is dying of cancer. He's in hospice care and one of the things we learned about these brothers is that they're so different that Finn suspects Max might be his half-brother. [laughter] What does this detail reveal?

Lorrie Moore: I think that something siblings often imagine in their own mind like, "Are we really related? How can we be siblings? We're so different." That's what he's feeling and he feels that the heroism really and the stoicism of his brother whereas he doesn't feel he really has those qualities at all. He's admiring his brother and being self-critical and also thinking, yes, maybe mom was romantic. [laughs]

Alison Stewart: The other thing we learn about Finn is that he enjoys a conspiracy theory. I'm going to read a little bit. Part of it is funny and then part of it's like, oh my, because there are people who believe this. At one point he's talking to Max and he says, "60% of Russians think America did not land on the moon. No one in Eastern Europe thought we did. They thought it was just Cold War BS." Max says, "Yeas, you're not fired yet." He said, "I split the difference. Say we did land on the moon, but perhaps later, not in 1969," which could very well have been enacted bogus stuff JFK's schedule honored Cold War pageantry who benefits boys and girls. Why did the Apollo program cease and desist as soon as the Soviets had deep space technology?

He goes on to say, as soon as women started becoming astronauts, we did stop landing on the moon. Why? Because women would not have kept their mouths shut about this. Still, not a single woman has landed on the Moon, Max is egging him on and he goes on to say, why did NASA send memos in December 68 saying, help, we cannot make this tight political schedule. Apollo 1 had blown up right on the launchpad the year before. As for ostensible loan assassins, I say to my students, what are some of the reasons James Earl Jones got all the way to Canada and then to London where he was robbed a bank and a jewelry store when money he was waiting for didn't arrive and then got to Portugal. How was it? This assassin was on the lamb for 65 days sponsored by somebody and it goes on and on and then his brother says, James Earl Ray, not Jones [chuckles]. How far down the conspiracy rabbit hole did you go looking for the conspiracies that Finn might engage in or did you make these up?

Lorrie Moore: I think he tries to reclaim the term conspiracy theories because they're not hallucinations, they're just skepticism of the official story. It is very weird that James Earl Ray was on the lamb for as long as he was. That's very weird and we don't talk about it. I could inhabit a fictional character and think about these things. It is a little strange that the first moon landing went off without a hitch and all the other moon landings really had trouble. You can see how people might be a little skeptical and there's no answers to any of these things and they're not conspiracy theories like Democrats eating children or Pizzagate. They're not like hallucinations. They're just trying to look at the official story and saying, is the official story all that convincing? Perhaps there's something else behind here. I think many people think that with the Lincoln assassination, we do know that John Wilkes Booth did assassinate Lincoln, there's no doubt about that but what happened to Booth afterward there was many, many rumors and I became interested in those rumors.

Alison Stewart: When you were writing that second part of the book, the part that consists of the letters and this idea that John Wilkes Booth might not be dead at all, what's your process for writing in the voice of someone who lived in the 19th century?

Lorrie Moore: I don't know. I was talking to my sister about that just yesterday. She said this voice is really, really convincing. I said I've been living in the south and when I was at the Coleman Center doing some research into that era I was reading a lot of diaries and letters but somehow the voice of this character I found quite easily in my head. I do think Southerners tend to talk in that way a little more than Northerners and I've been living in Nashville.

Alison Stewart: When you say that way, what was something you noticed about the way that people communicated at that time that you thought, yes, I want to incorporate this?

Lorrie Moore: I think Southerners are a little more picturesque and there's at least historically speaking now speech in America is getting all blurred and interestingly melted together and commingled but Southerners have typically valued a kind of storytelling speech, a kind of sweetness that may or may not be sincere and a wit and humor in their word choice. I think that's in Southern speech.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Lorrie Moore. The name of the book is I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home. The story is set, the modern part, in 2016. At one point Finn says to his brother, "To have a president so off script can never happen. He wanders so far off, he seems just to step off the planet as if the world were flat, and one could do that. Don't check out of this life thinking Donald Trump's going to be president." First of all, when did you write that?

Lorrie Moore: Well, I certainly thought that before he was elected. I thought he's not going to be elected. Did I write those sentences after he was elected? Probably, yes.

Alison Stewart: Why did you want to set it at this point at 2016?

Lorrie Moore: Well, as I said, there's this weird resurrection of the past, and that's part of the connective tissue between the section of the novel that takes place in 1870 and the section that takes place in 2016. The other things they have in common are the wheeling around of a corpse. There's one moment where Finn looks out the window after Trump has been elected, and he sees someone wheeling a fake John Wilkes Booth in a wheelchair with a Derringer. There is the sense of something unresolved about the South has come back, and helped to elect Trump.

Alison Stewart: What is the role of humor in this book and in your work, generally? How do you deploy humor?

Lorrie Moore: I don't know that I deploy it. I think I just observe it. I think it's just there. If you didn't include it, you would be ignoring it. My sense of things is that I just don't ignore humor. I let it be in the book. Now, I think the book is rather a sad story, but there is humor in there as there always will be. You can't go to a funeral without someone telling a joke. Funerals have started to be very funny. Memorial services, people get up, and they're telling hilarious stories. Humor is just there, but so are the tragic elements of life. They're sitting side by side. The humor is a connection between people and characters. It's also a way of hiding from sadness, it's also a way of dealing with sadness, it's also a release of tension and it's also an act of generosity between people because finally, people are trying to amuse each other, cheer each other up especially on car rides. There's a lot of the book that's taking place in the car, and so there's a lot of idle, quasi-humorous chatter going on in the car.

Alison Stewart: As I mentioned in the intro, it's been about a decade between this novel and your last. Are you someone who takes a break four or five years, and then begins writing again, or were you working on this the entire time?

Lorrie Moore: I'm always working on something. Between my last novel and this novel, I did have a collection of stories. Then I also had a collection of essays. I'm always working on something, but I also am a slow writer, and I teach. There are lots of competing elements for my time, but I am also slow. [laughter] I'm also slow.

Alison Stewart: As you mentioned, you live in the South. You're an English professor at Vanderbilt. What have you noticed is on students minds? I always love to ask professors who are teaching, what do kids who come in your class, what are they interested in learning? What do they want to know when they're in your class?

Lorrie Moore: It's very interesting because it changes through the years. It's different for graduate students, and it's different for undergraduates. Graduate students right now are very professionally-oriented. Many of them want to do novels and stories. They want to write short stories, but they want them to come together and be a novel because they think that's what publishers want and sometimes that's correct. My sense as a teacher is that students should write whatever they really have a burning desire to write, and not seek to please anyone. If you write the thing that you have a burning desire to write, it'll have some energy and some fire in it, and the publishers will come to you.

Undergraduates are exploring all kinds of things. A lot of them are exploring sexual identity, sexual orientation in ways, I think, that previous generations did not. It varies. I've been teaching so long that it-- it's interesting to me to see young people coming in with new interests that are different, but I'm starting to be the-- I'm not quite as old as their grandmothers. I used to be the same age as their mothers, but I'm much older than their mothers now. Not quite their grandmothers, but I'm getting there [laughs].

Alison Stewart: You could be the cool aunt. You're in the cool aunt page.

Lorrie Moore: I would love to be the cool aunt. [chuckles] That's fine.

Alison Stewart: Lorrie Moore's new book is I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home. Lorrie is speaking tonight at the 92nd Street Y, tomorrow at Books Are Magic and Thursday at Symphony Space. Lorrie, thank you for making time in your busy schedule.

Lorrie Moore: Thank you so much.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.