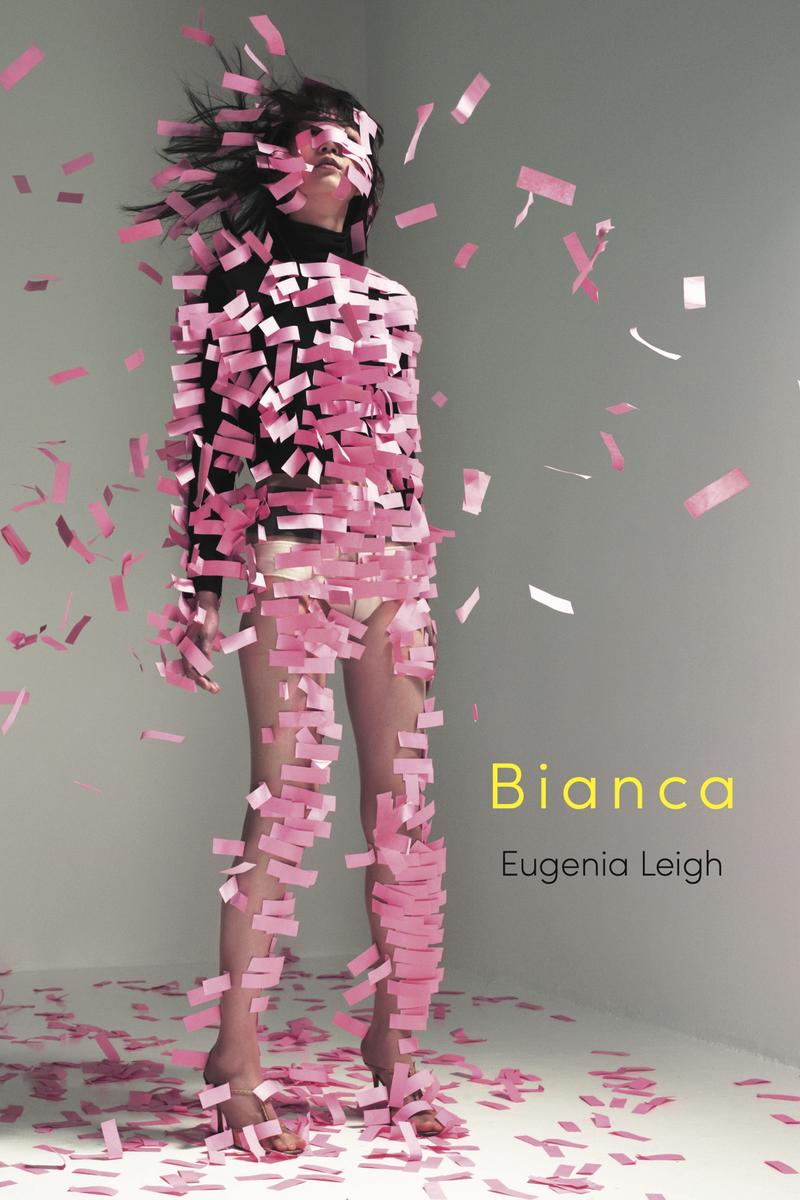

Eugenia Leigh's Sophomore Poetry Collection, 'Bianca'

( Courtesy of Four Way Books )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. A new collection of poems from Eugenia Leigh is titled Bianca. That's the name given to her, often manic alter ego. It's a pseudonym for Leigh's bipolar disorder. One of her poems starts;

We all called her Bianca,

my fever, my havoc, my tilt.

Bianca trashed the kitchen.

Bianca scratched the bleep out of me.

Bianca owes me a mattress,

owes me money, owes me sigs.

It was funny, sometimes it was a joke.

Bianca would spin the car up and down the highway

Night after night, she'd steer while picturing her rickety red Kia,

her silver Hyundai sliding down a track of ticker tape

unfurling, unfurling.

Psychiatrist, you would drink up to 10 alcoholic drinks a day every single day.

Then the minute you decide to stop, you just stop.

That's not alcoholism.

That poem goes on. The poems in the book offer accounts of Leigh's mental health struggles, her relationship with an abusive father who was a conservative Christian minister, her fears about her own parenthood, and her desire to break free from trauma that sometimes had a hold of her. Her poems have titles like Family Medical History, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder with Reveli's Theories of Time, and To The Self Who 12 years Ago Wrote A Letter To Me.

A Washington Independent review said Leigh's strips bear the concepts of stigma and shame, the harmful fallacy that we should bear out suffering alone and in silence. Eugenia Leigh is a Korean-American poet and author of two collections, Blood, Sparrows and Sparrows, which came out in 2014, and Bianca, which is out now. Eugenia, welcome.

Eugenia Leigh: Thank you so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: Would you start off by reading the poem, I Was Wrong About So Much?

Eugenia Leigh: Yes, definitely.

I was wrong about so much

About my brain, its wires glitching

like a jellyfish sprite

flashing its apple-red tentacles

above my countless thunderclouds.

About your eyes, not a savior’s eyes

but brown as blood.

I was wrong about the God,

I warped into a weapon, a garrison.

Wrong about love, too.

I thought love was my mother’s soprano tessitura screaming.

I thought love was a violence.

Verdi’s requiem, Dies Irae.

You thought love was love.

New-millennium emo. February

flooding the school below the palms

wringing their palms

like willows the morning after

you rinsed gas-station zin from my hair.

I’m sorry I chased you for years

the way a cowbird tails the cow—

not for love of the beast

but for the insects it kicks up.

She ditches her eggs

in someone else’s nests to do this.

Kills someone else’s young to do this.

This possessed. I was.

Alison Stewart: In an interview, you said for years you didn't realize Bianca was the book you were writing and you sent out to write something less personal. When did you realize, "Yes, I'm going to write something deeply personal"?

Eugenia Leigh: I think it might have been the pandemic, honestly. There were nine years between these books and during those nine years, I lived a lot of life. The first book was written in my 20s, and then I got married. I had two miscarriages. I became a mother and I also had the help of mental illness or mental health. I started to see a therapist.

Alison Stewart: Professionals.

Eugenia Leigh: Yes and I was diagnosed with CPTSD and bipolar II disorder. During the pandemic, my dad also resurfaced with stage four lung cancer. I had been estranged from him for about seven years. I think it was in the peak of the pandemic, I was home alone with my one-and-a-half-year-old, my husband was on the front lines as a healthcare worker outside of New York City. I just started realizing that I had to continue to tell this story. Also, l everything that I had thought about my story, about my history had changed completely. I had all these new perspectives.

As a mother, everything had been rewritten in my mind. I had never intended to write a sequel in a way of that first book but I suddenly had access to all this rage and all this pain that I didn't have when I was a child, or even a young adult child who was still writing these stories through those coping mechanisms blaming myself instead of blaming my father, which a lot of that first book did. As I was just writing for myself during the pandemic, I thought that we could all die. Nobody might see this, and that's okay. I think in some ways it helped me to isolate my brain, remember that I was doing this more for myself, and then let it all out.

Alison Stewart: When did you start referring to this alter ego as Bianca?

Eugenia Leigh: In my early 20s, I hadn't yet seen any mental health professionals. I was very high functioning. I had to work, I went to school, but I was also self-medicating with alcohol, with drugs and wreaking a lot of havoc during those seasons. My friends would, at one point, they even gave me a check and said, "You need to go see a therapist." I was like, "No, that's not me. I don't need help," but my bipolar disorder was really raging. My friends and I started to call this version of me Bianca. They'd say, Bianca was here last night and I wouldn't remember a thing because I'd blacked everything out. I was drinking too much. I would say, "Well, what did Bianca do?"

In some ways, that was my first experience of naming my disorder, of labeling, which helped me to distance myself from it, which then allowed me to treat it and to take care of that version of me and to recognize that there was a part of me that wasn't healthy, that I needed to speak to, that I needed to tend to. In some ways, this entire book has become that exercise in labeling and in naming

Alison Stewart: Eugenia, what did you hope people might understand a little bit about managing bipolar disorder through your poems or what it's like for a person managing it?

Eugenia Leigh: I think that looks different for everybody. I think one of the things that I had to grieve as I was writing this book, and I was visiting my own experience with bipolar II disorder is that I had a lot of privilege in having access to mental health help. I didn't get regular mental health help until I was married and had access to more money. To have psychiatrists and to recognize that the medications I'm taking now are so expensive, and there's still people in my immediate family who don't have access to that.

I think that I never want this book to be prescriptive to say, this is how you should deal with your bipolar II disorder or any other kind of mental illness. I think what I do want to point toward is that we do all need help, that we need, that there are resources out there. Even if we can't afford them, there are communities, maybe churches or places that do try to give funds to people who need extra mental health help, or we have-- That time during my 20s when I didn't have access to therapists, I had friends that I could talk to. They're therapist and we joke and we call it trickle-down therapy and say, "I'll see my therapist and then give you what I heard from her."

I think it's more a recognition that we at least need to process it and we at least need to talk about it. I think the more that we talk about it, the more people can have access to mental health help.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Eugenia Leigh, the name of the latest poetry collection is Bianca, it is out now. The very first poem is called What I Miss Most About Hell. I'd love if you could read it and we can talk about it on the other side.

Eugenia Leigh: What I miss most about hell is prayer.

I’d pack a plastic bottle with vodka,

drive to the crag of my life,

the parking lot of a pancake house,

and scream.

I prayed like everyone I loved was on fire.

The bright, violet blob I called God

would forgive the atrocities

roared in ethanol

while I’d shake like a dog

demanding answers from the maker of figs:

why the sycamore fruit

sweetens only when bruised,

the way a fist will ripen a child.

Alison Stewart: Why is this the first poem in the collection?

Eugenia Leigh: Ooh, that's a great question. I think this poem just encapsulates that experience of what it was like to be Bianca. During that time when I didn't know what to do, I was feeling so much pain and dealing with the repercussions of a childhood of domestic violence and of childhood abuse. My father was in prison for most of my teenage years. I still very vividly remember being a senior in college, bartending full-time, and going to school.

Something had been triggering for me. My dad had just been deported from prison as an option out of jail. I remember pouring Vodka into a plastic bottle and my roommates telling me, "You need to not do that and stay home." I did. This is a scene that literally happened that has stuck in my mind as a moment when I could see that there were so many people trying to help me but I was still very hardhearted, still not able to receive that help. I think in hindsight, I have so much compassion and grace toward that person who's-- This is almost 20 years ago, and I recognized that I was in so much pain.

In that pain, I didn't know who to talk to or who to reach out to. Sometimes it was an amorphous God, sometimes it was friends. I think that it's that place of questioning, that place of despair that I really wanted to capture, that I want wanted to capture what it was like to be in the thick of mental illness and to then figure out and articulate how did I get from that person to this person now as a mom, as a wife?

Alison Stewart: There are some harrowing stories in your poetry, some really, really hard things that have happened some hard things that you or Bianca did. There's one story, I won't give it away but somebody, a taxi driver, has an extreme act of kindness towards you. Why did you want to include that extreme act of kindness in this collection?

Eugenia Leigh: I think a lot of times when we're living with mental illness or when we're surviving trauma or abuse, we feel so alone. That scene comes in a story when I was really convinced that I was alone, that I had no family, that I had either squandered all of my friendships or all of my family relationships. I had hurt my father, and he had hurt me. I was convinced that I was okay with that, that that was just going to be my life. I had decided that this was my identity. This was my future. During that very difficult season, there were these characters like this taxi driver who had no obligation to extend kindness or love toward me, and yet, they did extend grace.

It got to a point where I couldn't ignore it anymore. Where I recognized there was kindness in the world, as much as I hate to admit it, as much as I had experienced so much violence and so much pain, there was love and there was grace. To grapple with that was something that I had to come to as well. That also contributes to the grief that I had. If there was this kind of love, why did I not experience it for so long? Why am I experiencing it now? If I am experiencing it now, can I have access to more of it? Can I give more of it to others as well?

Alison Stewart: You received your MFA from Sarah Lawrence College. Did you always know you were going to be a writer? Did you always know you're going to be this kind of writer?

Eugenia Leigh: No, not at all. It really took hitting rock bottom after college. I had seen my dad for a few months and had left him. I was a labor union organizer for a while, I thought I was going to go to law school for a while. At some point, I just hated my life. It was in my early 20s and I thought I don't know what I want to do with it. I had suicidal ideations. I thought to myself, I could die or I could just run away and do something that I love and see if there's a path there for me. I left Los Angeles, went to New York, got into graduate school somehow.

My first professor, Laure-Anne Bosselaar, a Belgian-American poet, she just let me cry in her office. She was the one who told me this is the story that you need to tell. I didn't know that I was going to write about my family or my history. I was writing these terrible poems about ex-boyfriends and she was the one who helped me to access this truth after a lifetime of lying about it of not telling people about it.

Alison Stewart: Let's finish quickly with Gold on 103.

Eugenia Leigh: Gold.

I've become the kind of creature who, on Sundays,

fills seven small boxes with a bevy of pills

to stick it out another week.

When will I be fixed enough

to hear my kid scream without tearing

my father's phantom hands off me?

How do demons, decades gone now,

still ravage me?

Tell me I am not the thing

my children will have to survive.

Tell me the mob I inherited

will not touch my son.

Yes, the cavalcade

of all that's tried to kill me

may forever raid my brain,

but know this:

in my mother's first language,

the word for fracture, for crack,

is the same as the word for gold.

Every Thursday for twenty-one months

before my son was born,

a doctor trained me to put the gun down

and write.

I understand

I am one of the lucky ones.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is Bianca. My guest has been Eugenia Leigh. Eugenia, thank you so much for being with us and sharing your poetry and your story.

Eugenia Leigh: Thank you so much.

Alison Stewart: That's All of It for today.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.