The Early Life of Playwright August Wilson (Full Bio)

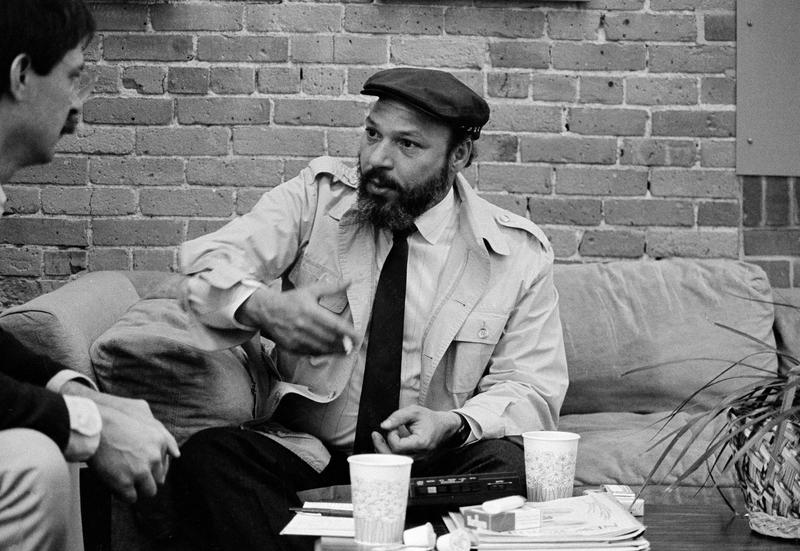

( AP Photo/Bob Child )

MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: City Song

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Hey, a quick reminder, it's time to get tickets for our November book club event. We are reading Rouge by author Mona Awad. It's the story of a woman named Belle, who investigates the mysterious death of her beauty-obsessed mother. Mona will join us at our live event on Monday, November 27th, at 6:00 PM at the NYPL, plus we have a live performance from our musical guests, Dear Deer. These events tend to sell out so you should head to wnyc.org/getlit to get your ticket. They are free, but you do have to reserve them. Go to wnyc.org/getlit to get your ticket for Monday, November 27th, and happy reading.

Now let's get this hour started with another one of our book series, Full Bio.

MUSIC - Luscious Jackson

Full Bio is our book series where we spend a few days discussing a deeply researched biography to get the full picture of the subject. This week we'll be speaking with the author of August Wilson: A Life, about two-time Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-winning playwright August Wilson. He was described by the Atlantic as the man who transformed American theater. Wilson was prolific and wrote an extraordinary 10-play cycle that traced various Black American experiences through the 20th century. The plays are Gem of the Ocean, Joe Turner's Come and Gone, Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, The Piano Lesson, Seven Guitars, Fences, Two Trains Running, Jitney, King Hedley II, and Radio Golf.

Award-winning journalist Patti Hartigan was a longtime staff member at the Boston Globe where she served as an arts reporter and drama critic. She met August Wilson in 1987 and interviewed him many times over the years, including in-depth for a long-form piece that ran just before his death in 2005. Hartigan book start before he was born in 1945, Frederick August Kittel Jr. to a German pastry chef and an African American woman. Hartigan begins by describing the formidable matriarchs in his ancestry, including his mother, Daisy Wilson, his grandmother, Zonia, and his great-grandmother, Eller, who had more than one run-in with the law in the mountains of North Carolina.

Let's get into our first conversation about August Wilson: A Life.

MUSIC - Luscious Jackson

August Wilson's family story begins on Spear Tops Mountain in North Carolina and we meet the matriarchs, his great-grandmother, Sarah “Eller” Cutler and there are a lot of stories about Sarah “Eller” Cutler on that mountain. What is one that's true and telling about who she was and what are some of the non-documented legends?

Patti Hartigan: Well, with that period of history, it's very hard to document. When the census takers showed up at the door, it depended on whose kids were there, who answered the door, who felt like they needed to give a different name, et cetera. The story of Willard Justice being held up there is absolutely true. That's documented in news many, many newspapers. The story behind it is what's a little fuzzy where why was he near her house? Why was he up on the mountain? What were they chasing him for? We don't know, but that scene that I painted the very beginning of the book actually happened.

Alison Stewart: Her daughter, Zonia, worked as a domestic and told people that a white man had raped her and that her children, August Wilson's mother included, Daisy, were the result. Zonia died when August Wilson was five, and he only learned about her through his mom, but he does name a character and Joe Turner's Come and Gone Zonia. Why would he name a character after a woman that he really had no memory of?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, because he honored all the ancestors. He wrote from what he called the bloods memory, especially the matriarchs were very, very important to him. He worshipped his mother, Daisy Wilson, and he didn't know Zonia, but she represented the link to the past. There's a Cutler, in Ma Rainey's Black Bottom and he knew that that was a family name. How much of the actual history he knew, I don't think we know that. He never went to Spear North Carolina. It was a question of people made the great migration and they didn't want to go back. They were looking for a better life.

He felt in his blood. It was uncanny some of the similarities of the things that I found in his ancestral history and things that appear in the plays.

Alison Stewart: What's another example?

Patti Hartigan: Well, his great-great-grandfather, Calvin Twitty, I found a will of a plantation owner, it was a Twitty plantation and there was a Calvin listed in the list of enslaved people. In that same will, the owner left a piano to his daughter and there's a play called The Piano Lesson. Also around in Spruce Pines, which is the largest town near Spear, there was a black man named John Goss who was accused of raping a white woman. It was based on her testimony, her testimony alone, he was working on a chain gang. Then in Joe Turner's Come and Gone as you know, Harold Loomis, just got off seven years working on a chain gang.

Alison Stewart: August Wilson's mom, Daisy Wilson, arrives in Pittsburgh in 1937 and she's awed by everything she sees in this area known as The Hill and The Hill becomes an important character in the story and the life story of August Wilson. Can you describe The Hill and its origins?

Patti Hartigan: Well, The Hill when August Wilson was growing up there, was a very mixed race area, was where he called the the unwelcome, all set up on The Hill. It was the kind of place in the '50s where everybody was an auntie. All of the women could yell at any kid if they caught them doing something wrong, and it had a real community feel. There was a watchmaker who lived next door to the Wilsons. There were seven sisters who all stayed in the neighborhood, the Klancy sisters, it was a real community. It had paint stores, and barber shops, and theaters and it was lively when he was growing up.

Alison Stewart: Daisy had several children including Frederick August Kittel Jr. born April 27th 1945. His father was a European pastry chef is how he's been described some time. It's with whom Daisy would have several children. How much did August Wilson, then Frederick August, know about his father?

Patti Hartigan: He was an absent presence in the home. He was not particularly well regarded. August Wilson looked to a boxer who lived across the street named Charley Burley as a surrogate father. When Frederick Kittel did show up, he was frequently intoxicated, angry, throwing things, the children knew that-- some of them would hide and one would run across the street and get Charley Burley.

He said in an interview in The New Yorker, that he only had one memory of his father, he took them downtown to buy some Gene Autry boots and the anecdote is that his father told him always to have coins in his pocket and jiggle them. That was his way of telling August Wilson, "You need to look like you can pay here, you need to be established."

Alison Stewart: I thought it was interesting, though, that Daisy gave him Frederick August Kittel Jr. knowing that he wouldn't necessarily have access to his father.

Patti Hartigan: She desperately wanted a boy. Maybe in those times, everybody named their firstborn son after the biological father. Well, we'll get to it later, but there is a story that she didn't marry him until he was very sick and dying. She did that because he had another wife. When Kittel's wife died, Daisy said, "Well, let's get married." Then went to a different courthouse. They didn't go in Pittsburgh, they went to a different county, so no one could know. According to Richard Kittel, Wilson's younger brother, she was doing it so they would get benefits when he passed.

Alison Stewart: His mother sounds like a wise woman.

Patti Hartigan: Oh, yes. Oh, my gosh.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Patti Hartigan. The name of her book is August Wilson: A Life, it is our choice for Full Bio. Frederick August could read by for he was a smart kid, high IQ. He had a stutter. How did having a stutter shape as young life?

Patti Hartigan: I think it made him perhaps a little shy and a little defensive. I happened to find someone who went to kindergarten through third or fourth grade with him and he's the one who told me that he stuttered. There are characters in Wilson place who have speech impediments, but no one ever knew that it was him in his childhood. I think it made him quiet. If he was called on, he always knew the answer, but he didn't raise his hand. If someone challenged him, he could very quickly get angry. That comes from being a little, when you have something like that, you might be a little insecure.

Alison Stewart: He experienced some racist bullying in school, especially at Catholic school, and it clearly stayed with him as an adult. What was the story that he would recount of that time over and over again?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, when he went to Central Catholic High School, you have to understand this is an elite exam school, and your parish sends you, and your parish pays for you. He shows up and he is a voracious reader, he's read everything, he wants to learn. There were notes left on his desk every morning using offensive words. I went to the school and I walked the same path. At recess, they didn't get to play ball and they didn't get to do anything, they got in a line and they walked in a circle. As he walked in the circle, someone would step on his shoe, or kick him, or throw a potato chip back at him and then pretend that they hadn't done it, and he knew clearly what was going on. He was not welcome there.

Alison Stewart: Even the adults, he was accused of plagiarism at one point. It was a black teacher who accused him, though.

Patti Hartigan: Yes, this is a different school. He left Central Catholic because he just couldn't take it anymore, and then he went to a Technical High School where he couldn't get into automotive and they had a make him [unintelligible 00:11:30] and he felt the academics were beneath him. He went to the final High School, Public High School, and he liked this teacher, he called him Mr. B. They were assigned to write a paper. August Wilson went, he wrote a 20-page paper on Napoleon, he had footnotes, he typed it himself. When he brought it in, the teacher said, "Put it down," and said, "You are either getting an A or an E."

Now, an E at the time was a failing grade. August Wilson said, "What do you mean I'm going to get an E?" He said, "Who wrote this? You have older sisters." He said, "I wrote it." He wouldn't defend himself any further, so the teacher wrote E on it and August Wilson threw it in the trash basket, left school, hoping for three days that someone would come and find him and apologize to him and make things right. He went and he played basketball on the court outside the school every morning for three days and no one ever came, so he dropped out.

Alison Stewart: He said, "I dropped out of school but I did not drop out of life."

Patti Hartigan: Right, he went to the Carnegie Library, and he hid this from his mother, he didn't tell her he had dropped out of the third school. He went to the Carnegie Library every day and he read and read and read and read. He was a complete autodidact, he devoured books. He saw a shelf, which at the time said Negro books, I think, and he just read every single one of them and he was so inspired. At that young age, reading James Baldwin, he said, "You know what, I can do this."

Alison Stewart: Daisy was not pleased when she found out that he had dropped out of school. She was really hard on him. You write in the book, she's described as denying him food, banishing him to the basement, and it seems like it took him years to try to make this up to her or to get her approval.

Patti Hartigan: Yes, it did. He said it once in an interview, he had an IQ of 143. He was her great hope, she wanted him to be a lawyer. He wanted to be a poet, poets don't make money. You can't feed your children with words, you need bread. She was so sorely disappointed in him, and yes, he did always want to make it up to her. When he finally had Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, he said, "Mom, I got a play and I'm doing well with this." She said, "You'll be a writer when you're on TV." It wasn't until the Piano Lesson, the film teleplay for Hallmark Hall of Fame was aired that he was finally on TV, and she had passed by that point, but he did look up and say, "Look, ma, I did it."

Alison Stewart: You're listening to our Full Bio conversation about August Wilson with author Patti Hartigan. After the break, we'll learn when and why Frederick August Wilson changed his name and how Bessie Smith and Romero Burden inspired his writing.

MUSIC - Luscious Jackson

This is All Of It on WNYC, I'm Alison Stewart. We continue our full bio conversation about two-time Pulitzer Prize and Tony-winning playwright, August Wilson. Patti Hartigan is the author of August Wilson: A Life. August Wilson worked as a dishwasher and a short-order cook. He even did a stint in the army, but his real desire was to write and he began as a poet while living in Pittsburgh.

During this time, he was also figuring out who he was as we'll hear. That said, Wilson was always clear about his identity as a Black man, even though family members of his decided to pass for white. He was often questioned about it throughout his career as he was during his appearance at Town Hall in New York City in 1996. This audio is from Fresh Air.

August Wilson: I recognize all myself, first of all, my father was German. What about it? I don't know. I mean, I don't know what else-- The cultural environment of my life is Black. I make the self-definition of myself as a Black man, and that's all anyone needs to know.

Alison Stewart: He and some other Pittsburgh poets began a community theater called Black Horizons in 1968, and playwriting became his focus. We will learn how it happened in our conversation with Patti Hartigan, author of August Wilson: A Life.

MUSIC - Luscious Jackson

In your chapter, A Period of Reinvention, we begin to see the beginnings of August Wilson as opposed to Frederick August Kittel, Jr. When did the name change?

Patti Hartigan: He changed his name, he told the story over and over and over again. He changed his name on April 1st, 1965. That was the day that his father passed, he doesn't include that when he tells the story. He had just received $20 from his sister for writing a paper for her, she was a student at Fordham University. He took the $20 and he went down to McLaren's typewriter store and he bought a used Royal Standard typewriter. He carried it back up the hill because he didn't have any money left, and he put in peace of, you remember that onion skin? He put in the paper and he typed all different versions of his name. He settled on August Wilson, which was a tribute to his mother.

He repeated that story, but he never told anyone that was the day that his father passed. I found that in the courthouse and in historical records and newspapers. There's something even more poetic about him just changing his name on that day because he had the new typewriter, he was rechristening himself.

Alison Stewart: He also was trying on new personas, affected some accents, occasionally, code-switching between highbrow literary language and street vernacular, wearing tweety jackets and caps. As a young man, what was he looking for?

Patti Hartigan: I think he wanted to be the next great poet. Really, that's what he was looking for. He read voraciously, he read all the poets. He claimed he didn't read dramatic literature when he decided to become a playwright, but he knew his poetry. He was a great fan of Dylan Thomas. And he had always had a legal pad and a pen or pencil with him and he was always writing. If he didn't have that, he was writing on a napkin. He felt in his, in his blood that he was a poet. You see it when he became a playwright, the monologues in his plays, just so are like poetry. He had that training before he started writing plays.

Alison Stewart: How did he make ends meet? People of his age at that time don't often make a living writing poetry.

Patti Hartigan: Right. Well, he did. People [unintelligible 00:18:46] older than he does to make a living writing poetry. He had every odd job you could have, in his one-man autobiographical show, How I Learned What I Learned, he intersperses different jobs he had, cutting lawns, washing dishes, short-order cook. He did those jobs to pay the rent and then when he walked out, he took his apron off, and he put his tweed coat on and he was a poet.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Patti Hartigan. We're talking about her book, August Wilson: A Life, it's her choice for full bio. He always always always identified as a Black man, August Wilson did, even though he could pass as he had a brother who did pass for white. Over the course of his career, interviewers and reviewers would bring up his white lineage, almost as a challenge to his blackness and he would get really, really ticked off.

Patti Hartigan: Yes, it wasn't a brother, it was his uncle, Ray.

Alison Stewart: Uncle, thank you.

Patti Hartigan: Yes. He got angry and he self-identified. Every human on the planet can choose to identify however they want, but people wouldn't leave him alone about this. He said repeatedly, he talked about Daisy's Kitchen and that the culture he learned there, the ethics, the values, everything he learned there, the songs, the food was Black culture. That's how he chose to identify. There are examples in the book of some really rude people asking him this question and not stopping even when he clearly said, this is who I am. Let's move on to the next question.

Alison Stewart: When did he begin writing poetry?

Patti Hartigan: Oh, he wrote poetry in Central Catholic. [laughs] He wrote poetry. Actually, he wrote poetry in middle school because he told a story about leaving poems for a girl he had a crush on in the Cat parochial school he went to. He was always writing. When he left school, he started writing more seriously and then when he met his fellow Poets on the Hill, he really fashioned himself as a poet. He was a poet who worked a day job, but he was still a poet. He gave readings. There's a wonderful video of August Wilson and some of his colleagues going to Oberlin College, where they did a reading and they did some activism. He looks very young, and he read all the time.

Alison Stewart: You include one of the poems that he had published about Muhammad Ali. It says, "Muhammad Ali is a lion. He's a lion that breaks the back of the wind, who climbs to the end of the rainbow with three steps and devours the gold. Muhammad Ali with a stomach of gold whose head is a lion."

Patti Hartigan: I don't know whether they ever met. Wouldn't that be fascinating if they did? He did meet Hank Garrin. He met a lot of his heroes.

Alison Stewart: Oh, I'm sure. You write about how August Wilson, things changed for him one day in 1973 when he sat down and wrote what he called his morning statement. It said, "It is the middle of winter, November 21, to be exact. I got up, buckled my shoes. I caught a bus and went riding into town. I just thought I'd tell you." What was the purpose of this morning's statement?

Patti Hartigan: He had been writing this highfalutin poetry. He'd been wearing tweed and adopting a Dylan Thomas accent. I think this was his way of saying, this is direct. This is a morning statement. There's no questions in it. Take it on face value, this is what it is, and this is who I am. For him, that was so freeing.

Alison Stewart: August Wilson cited as his influences the four Bs, Bearden, the Blues, Baraka, and Borges. Where do we see an example of, let's start with artist Romero Bearden.

Patti Hartigan: Oh. The Piano Lesson, the name of the play, is taken from a Bearden collage. Bearden lived in Pittsburgh for a while. Some of his collages and paintings depicted the people that August Wilson grew up with. He would look at them, and I wish I had a copy of the piano lesson in front of me. Even Joe Turner's Come and Gone, there was a man sitting in a boarding house, and he had an abject look on his face.

He was broken. He was distraught. August Wilson said, "What is going on with this man? This man who could be my uncle, who could be the guy who lived next door to me?" Then he wrote his masterpiece, Joe Turner's Come and Gone based on what he saw in that image. Bearden was a remarkable influence. He wrote the introduction for a sweeping biography of Bearden, and he talked about how his whole world changed when he saw these images

Alison Stewart: As a young man, he became acquainted with the Blues. Specifically, Bessie Smith's, Nobody in Town Can Make a Sweet Jelly Roll Like Mine. Let's listen.

Patti Hartigan: Ooh.

MUSIC - Bessie Smith: Nobody in Town Can Make a Sweet Jelly Roll Like Mine

In a bakery shop today

I heard Miss Mandy Jenkins say

She had the best cake, you see

And they were fresh as fresh could be

And as the people would pass by

You would hear Miss Mandy cry

Nobody in town can bake a sweet jelly roll like mine

(Like mine)

No other one in town can bake a sweet jelly roll so fine

Alison Stewart: What was it about that song that he would come back to and say, "Yes, this was foundational to my writing?"

Patti Hartigan: Oh, her voice and the way she spoke to him, the sultry, the sexy, it was replete with the culture that he loves in Daisy's kitchen. He said he played it over and over again, 29 times, or something like that. Actually, I did interview the woman he was briefly living with at that time, and she said, "Oh, yes, he did." He never played the other side. It was a music that spoke to him, and he talked about it later on in his life too when he was writing King Headley II, which is set in the 1980s, which was a decade he didn't really relate to.

He said he was going to listen to hip-hop. He said he was going to listen to rap, and he couldn't do it. He listened to the blues while he was writing the play. He said, because the current generation, the generation of artists in the '80s, had learned everything at the foot of the blues.

Alison Stewart: The last two Bs are rioters. Poet Amiri Baraka and Jorge Luis Borges. What was it about Baraka that inspired him?

Patti Hartigan: Oh. He was big in the National Black Arts movement. He believed that art and culture could perhaps bring about social progress. August Wilson and his friends had a theater called Black Horizons, which was modeled after it. I think it was in 1968 the Drama Review put out an issue of on Black theater. I have it. He said he got it and they all read it, and they passed it around, and it was so dogeared. They still kept it and they did every one of those plays. Baraka's Play of Black Mass was in that collection, in that scholarly review. They did that play with Black Horizons.

Alison Stewart: Finally, Jorge or Jorge Luis Borges, he was an erudite Argentinian writer.

Patti Hartigan: I know. He always mentioned that he didn't really talk about it much except for once. His play, Seven Guitars, begins at the end. He didn't start at that way, but he changed it at some point. It begins right after a funeral, and then it goes back in time and it takes you through the story of how the person died. August Wilson said that he had read a story by Borges in the New Yorker that used that technique of telling you what happens in the very first sentence. Then the mystery is, how did it get that way? That intrigued him.

Alison Stewart: Before we wrap up today, I did want to ask about the Black Horizons Theater. You mentioned that. Tell us a little bit about the origin of it and why August Wilson and his friends started it.

Patti Hartigan: That's a really good question. Rob Penny, who was part of the Center Avenue poets, was writing plays. They did believe that the arts could build community and could build confidence and self-confidence. They started this theater, and none of them really knew what they were doing. Nobody wanted to direct, and so they pointed at August Wilson. He said, "I don't know how to direct." He went and got a book out of the library. They did these plays and it was true community theater in the spirit. It probably cost 50 cents. Everybody. It was okay to bring your whole family and kids could run around in the aisles.

They were eager to do these plays written by Black people in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was a formative experience for him, although he really didn't know how to direct. Apparently, when he was directing his first play, he came in, everybody sat down, and he said, "Let's read the play." They read the play, a table read, and the actors looked at him and said, "What do we do now?" He said, "I don't know. Let's read it again."

Alison Stewart: That was Patty Hardigan discussing her book, August Wilson: A Life. On tomorrow's Full io, we'll hear about Wilson's longtime collaboration with Lloyd Richards and how his play, Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, changed Wilson's life.

MUSIC - Luscious Jackson

Armenian-born pianist and composer, Astghik Martirosyan, combines the traditional folk music of her homeland with her jazz training. She joins me next to perform live in studio.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.