Documenting Chinatown's Organized Crime History

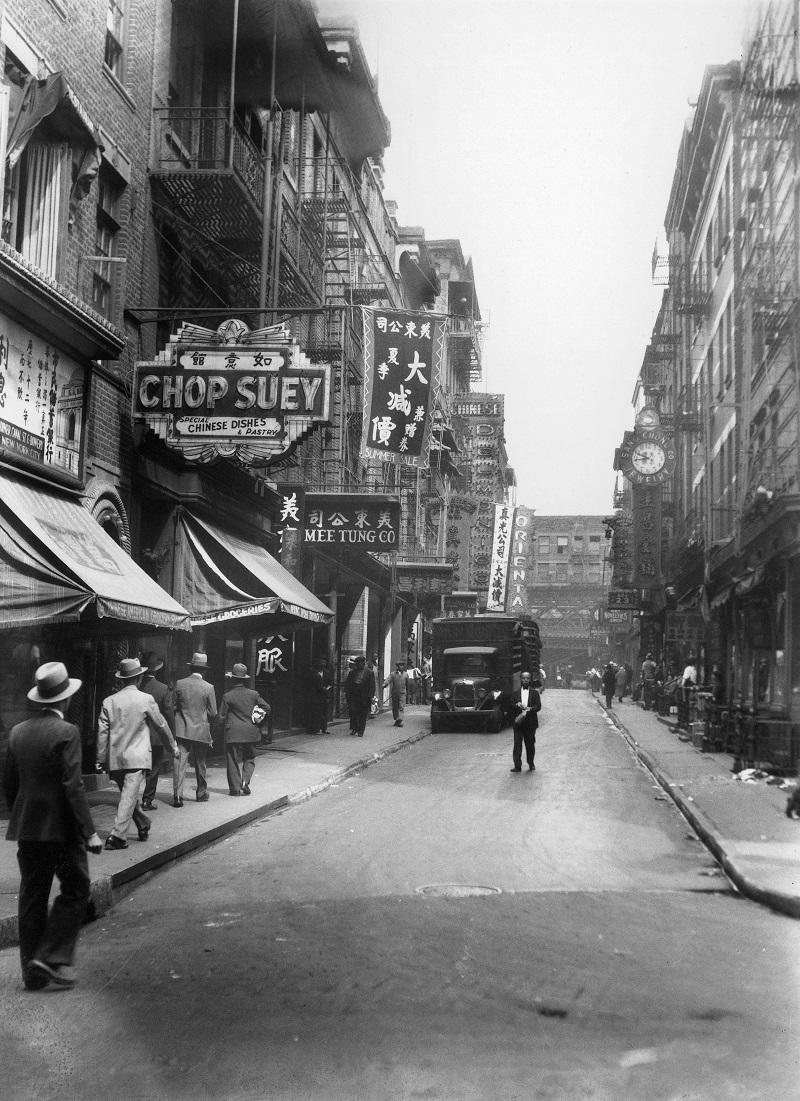

( Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images )

[music]

Kerry Nolan: This is All of It. I'm Kerry Nolan in for Alison Stewart. Thanks for spending part of your day with us, whether you're listening on the radio, live streaming, or on-demand. On today's show, we're inviting you to call in for all of our segments. You know more and more women are choosing not to have kids, including comedian Chelsea Handler, who received a lot of attention last week for her daily show segment about child-free women. We'll talk with Sociology Professor Amy Blackstone, and we'll take your calls. Lent starts tomorrow, so for Christians depending on where you're from, today is a day to eat the good stuff.

Pancakes, beignets, donuts, and of course, king cake all before the culinary austerity of Lent. We'll talk Mardi Gras and Shrove Tuesday food traditions, and we want to know how you note the day. We'll take your calls then as well. That's the plan. Let's get this started. We have an hour looking at the history of organized crime in New York City. There's a relatively new YouTube series out called Chinatown Gang Stories, featuring video testimonies from people who were involved in some of Chinatown's gangs in the '70s and '80s.

While we've seen a lot of history and a lot of pop culture about the Italian Mafia. and a number of Black exploitation films about criminal enterprises in Harlem and other Black neighborhoods. A lot of the depictions we get of Chinatown's gangs are based in stereotype, not sound research. Enter Michael Moy, he used to be an NYPD detective, but before that, he spent nine years of his youth as a member of a Chinatown gang.

Now Mike has made it his mission to document the history of organized crime in New York City's Asian gangs. He's got a police officer's investigatory impulses, and you can hear in his interviews with former gang members how he gathers testimony like he's building a case. He's also got a familiarity with his subject's past because he's lived them. Let's talk about this effort to build out the historical record of this important piece of New York City crime history with Michael Moy. Mike, thanks for joining us today.

Mike Moy: Hello, how are you?

Kerry: Good.

Mike: Thank you for having me here.

Kerry: It's our pleasure. Listeners, let's try to bring you into the conversation. Did you live in Chinatown during the heyday of these gangs? What was your experience? How was your day-to-day life affected? Give us a call at 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692. You can also tweet us or dm us on Instagram. The handle there is @AllOfItWNYC. Mike, there are several specific gangs that you're working to document, the Canal Boys, the Ghost Shadows, and the Flying Dragons. Give us a sense of, I don't know, the landscape of these organizations. What were the ways that they were different from one another?

Mike: The gangs that were relevant during the 1970s into the '80s were the Flying Dragons, Ghost Shadows, and the Tong Leong. These were the three major gangs that rule Chinatown during those times. Then later on, it was the late '80s when the BTK came in. BTK originally was known as the Canal Boys, and they were predominantly Vietnamese, and they branched off from the Flying Dragons. Some of them were from the Ghost shadows as well. They acted differently. They didn't go according to the rules that was established by the Chinese gangs during that time. That's why there were a lot of friction between the Vietnamese gangs and the more established traditional Chinese gangs during that time.

Kerry: You talk about the BTK and the Canal Boys flouting the rules that the Chinese gangs had established. What were some of those rules?

Mike: Usually when a gambling house is protected by another gang, for example, if a gambling house on Pell Street is protected by the Flying Dragons, the Ghost Shadows wouldn't go there and rob the gambling house. BTK they were robbing the business establishments around Chinatown, or the gambling house, and even the gang members themselves.

Kerry: Can you help us understand a little bit about how these gangs recruit young people by talking about your own history? How did you wind up as a member of a gang?

Mike: They usually do recruiting at the school, usually a high school or a middle school, or a lot of times they would hang around the places where these kids hang out at the park and they do the recruiting over there.

Kerry: How do they determine what kid would be a good recruit and which one is not worth your time?

Mike: Oh, well, basically they size you up and see if you are easily influenced if you are a follower or you have leadership qualities. They basically size you up and these guys who does the recruiting they're usually a little older maybe around 17, 18, and they would recruit the younger kids, anywhere from 13 to 16.

Kerry: 13 to 16. Wow.

Mike: Yes.

Kerry: How did civilian members of the Chinatown community feel about these gangs? Did they feel protected or did they feel terrorized?

Mike: They don't really interact with the gangs. There's really not much interaction between the community and the gangs. I guess there's anxiety there getting caught in the crossfire if anything happens. Usually, there's really not too much interaction between the community and the gang members.

Kerry: If you're just joining us my guest is Michael Moy. He is a crime historian. He's got a YouTube series called Chinatown Gang Stories. He is a former gang member himself and a former New York City police detective. We want to hear from you if you grew up in Chinatown in the '70s and '80s and these gangs were a part of your everyday life. We want to hear from you, we want to hear your story. Give us a call, 212-433-WNYC. That's 433-9692. You can also DM us on Instagram @AlOfItWNYC, and you can do that on Twitter as well with the same handle.

Mike: Also another thing I like to add is how the movies portrayed us terrorizing the residents of Chinatown. It's usually the kids our age during that time, the teenagers, those are the kids who were probably afraid of getting recruited by the gangs. As far as the resident themselves we really don't interact with them too much. It's not like we go extorting from every store and they're trying to put the store out of business-- how the movies portrayed us to be.

Kerry: Let's take a call. Eddie in Manhattan. Welcome to All of It. Hello. [background conversation] I guess that phone call's not going to work for us. Let's get back to our conversation. We are talking about Chinatown, Michael, but where specifically were some of the important landmarks of these gangs in the area?

Mike: The Flying Dragons they had control of Pell Street and Doyer Street. Mott Street and Bayard Street was controlled by the Ghost Shadows. Then the Tong Leong controlled Division Street and East Broadway. The Canal Boys controlled a piece of Canal Street. The Fuk Ching had Eldridge Street and Catherine Street, Chrystie Street around there. Then you had the Green Dragons. The Green Dragons had Queens, Flushing and White Tigers also had Elmhurst in Queens. Then you had the lesson known gang Tong Sing, they had 8th Avenue in Brooklyn. These were the gangs out there during that time.

Kerry: In one of your videos, you're talking with a man with the name Bighead about how long the Green Dragons were around compared with the Canal Boys. The Canal Boys they were notorious and infamous, but they were also only around for about five years, you said. How did these gangs come into being? Let's talk a little bit about why they may have fallen apart.

Mike: A lot of these gangs branched off from the older gangs. It was the White Eagles in the beginning, during the 1960s. Then the Black Eagles branched off from the White Eagles. With the Flying Dragons, the Canal Boys branched off from the Flying Dragons. There was a lot of internal civil war amongst the gang. Even the Ghost Shadows they branched off into two different faction. The Ghost Shadows eventually they branched off to the Mott Street faction and the Bayard Street faction.

Kerry: You mentioned in your introduction video, and we did talk a little bit about this that Asian gangs are frequently featured in crime movies and on TV, but the people who actually live these lives have really never come forward to tell their stories. What do you see in these media depictions that makes you sit back and go, "This is completely wrong. This is not what these gangs look like or how they operated." What's the difference between what we see on TV and in the movies and what happened on the streets?

Michael: They made us seem like we're trying to put the commercial establishments out of business. That's not true.

Kerry: It was just a shakedown rather than destruction?

Michael: Yes. Basically, we work together with the store owners. The store owners they understand that we were kids, we just wanted money to eat. That's all we wanted. It's not like we're shaking them down like, for example, how the Italians do it, where we're going to shake them down and eventually we're going to own the business. That's not how weA-- we just want a meal or something.

Kerry: You just wanted to get paid.

Michael: Just get paid.

Kerry: Can we talk more about your personal history? I mentioned that you became a police officer after being a gang member for about nine years. In part, it was the story of Steven McDonald, the NYPD officer, who was shot and paralyzed while on patrol in Central Park whom he later forgave his attacker. What was it about his story that inspired you to try to test into the NYPD Academy?

Michael: I was following Steven McDonald's story, and I was reading every single article that came out about Steven McDonald. At one point, he said he forgave the kids who did that to him. In my mind, I couldn't understand how he could forgive someone who shot him right and left him paralyzed. It's something that I couldn't understand because I grew up in Chinatown. Growing up in Chinatown, watching these show baller movies, these kung fu movies, it's all about revenge. It doesn't matter how long, you have taken revenge.

I just couldn't grasp that concept about forgiving that person who did this to you. Something he said about why he forgave because-- he said something like, "They were a product of the environment." I didn't understand what that meant back in those days. I dissected every single word what he said and tried to analyze it. Then I did some self-reflection, "Am I a product of my environment?" I never heard that term before. That was back in the '80s.

That's when I realized, "Maybe I need to get out." In 1989 of January I took the police exam and I left in the back burner. In 1993, they called me to be a police officer, but I guess I still wasn't mature enough and I turned it down. Then in 1995, that's when I made the move to become a police officer. Steven McDonald played a big role in it because if it wasn't for him I wouldn't be able to take that first step. The first step is realization. Once you realize what you're doing wrong, then you take the next step to make that change.

Kerry: Let's take a call. Ellen in Los Angeles. Ellen, welcome to All Of It.

Ellen: Hi, how are you?

Kerry: Good. Thanks for calling.

Ellen: Good to be here. This is really interesting calling because my first encounter with a gun was in high school was freshman year. I went to school at Bronx Science, and BTK and Canal Boys used to hang out there. I don't know if they were there recruiting necessarily because maybe they lived in the Bronx. We had friends that knew them. A friend of mine dated one and he asked her to keep his gun under her bed.

We lived in Queens. I went to her house after school one time and she just asked me, "Do you want to see what's under my bed?" It wasn't a shoebox. It was just under her bed. I thought it's something that-- the gangs in that time, it was early '90s not quite the '70s and '80s, but it was still around. My first encounter with gangs was in junior high school in Queens.

Kerry: Thank you for your call, Ellen. Michael Moy, was it hard to tell your fellow police officers about your experiences with the gangs? How did they react to that?

Michael: I never told anyone.

Kerry: No? Okay.

Michael: They probably found out through my channel. [laughter]

Kerry: Let's listen to a clip now from a conversation you had with China Mac, who is a member of the Bayard Street faction of the Ghost Shadows. Here he is answering your question about when he entered the gang, and whether his faction was in a civil war at the time with the Mott Street faction. Let's listen.

China Mac: At this time, I was so young. I was probably 12, 13. I don't even think I was 13 yet.

Michael Moy: What year?

China: This was 1995, 1996, something like that. I don't remember exactly the year, but I know I was still in junior high school. I was 12 years old, 13 years old. Then we all ran outside, I didn't know what was happening. Then when I came outside, I seen maybe 16 to 20 people walking up the street, and they all had pipes and knives and stuff. I was like, "Whoa." Everybody started, "Go get the stuff." We had pipes and machetes and everything hidden on the street, on the gates.

Everybody was running inside, grabbing stuff, grabbing stuff. Then Siu Bo, he was one of the kids that was there. Basically, when I walked out I seen one of the guys run up on Siu Bo and stab him to death. I was just stuck there for a minute until one of the older guys grabbed me like, "Yoh, move." That was my third day there.

Kerry: Whew, first of all, that's an amazing story from former gang member China Mac. We also hear some of your detective skills as you're conducting these interviews. You're looking for specific timelines, and we can hear you trying to fit this testimony into the bigger picture. What pieces of your work in the NYPD have you found helpful as you started to document this history?

Michael: I like to go with the facts and interview as many people as possible and put the pieces together.

Kerry: Let's take another call. Peter in Greenwich Village. Hi, Peter. Welcome to All Of It.

Peter: Yes. How are you? I have a question. How did your gang or Chinese gangs interact with the Italian gangsters?

Michael: With the Italian? There was mutual respect and we had a good relationship with them, especially the mob guys. It's just that the younger generation of Italians, those were the troublemakers-- the young Italian kids. We're talking about the teenagers. The older Italian guys-- we were only 17 to 18, in our 20s and we were dealing with the mob guys who were in their 30s and we had a mutual respect for each other. Dealing with the Italian kids around our own age there were a couple of incidents between us where there were some shootings, but they were at the losing end of the battle.

Kerry: Did you have very specific turf that you didn't cross over on between-

Michael: We didn't go into Little Italy. We didn't make any trouble in Little Italy.

Kerry: That makes sense.

Michael: One time somebody tried to mediate a situation between the Black Eagles and the Ghost Shadows because Black and White Eagles had a war going on with the Ghost Shadows. The Italians tried to mediate it, but there was some gunshot that went through-- I don't know which crime family the Italian was linked with, but I can find out through my sources. He had a jewelry shop in Chinatown. When he tried to mediate the situation, there was some shots fired into his store. That stopped the Italians from interfering with their business.

Kerry: When we checked yesterday you had 13 videos uploaded to your channel, and most of them are in an oral history style. How have you been deciding what pieces of the broader history of these gangs to explore and how do you decide who to interview?

Michael: I started the channel interviewing my friends, people who I had personal dealings with and then I expand from there. It's not easy to find these people to come on the channel to speak about their experiences. Everyone on this channel I had prior dealings with as a gang member. That's why they know my character. They know how I am, and they trust me enough to come on this channel.

Kerry: Do they have any particular concerns about sharing their stories, or have you built up, I don't know, a bounty of trust with them so that they feel okay?

Michael: Yes, there's a certain level of trust and respect that they have for me. Of course, they're concerned about speaking about their stories, but they're not concerned about going back to prison because they already served their time for what they did already-- not talking about any other open cases. No, there's no concern there about going back to prison. The only concern they have is how their friends and family would view them.

Kerry: What do you know about who's following your work? What kind of people are watching and commenting and giving a thumbs up, thumbs down on these different interviews? Also, are you surprised that there's a very engaged audience for this history?

Michael: I'm very surprised because when I start this channel, on the first day I had three subscribers and I thought, okay, there's really no interest in this topic. I didn't think it was going to expand to the-- current day I have 10,000 subscribers. I'm checking the analytics and I see that most of the people who's watching these videos are from 30 to 45 years old. I couldn't believe it because I thought it would only be people in my age group who would be interested in these videos. To my surprise, it was the younger kids, the younger generation.

Kerry: What's your assessment of any gang situation in Chinatown today?

Michael Moy: Oh, there's no more Ghost Shadows and Flying Dragons. Those days are over. The gangs nowadays in Chinatown they're all about making money. It's not about violence. They try to avoid violence as much as possible. Of course, they're still gangs out there, but they will avoid the violence because they learn, they've evolved. It's all about making money now. They know that violence is going to bring attention. That's one thing they don't want, is the attention.

If you are walking in the streets of Chinatown, are you able to identify who's a gang member or not? No, you won't. It's because they're staying on the radar and now they operate in cells, sort of like a terrorist group. They operate in cells. There's no gang name for them. We're talking about New York City Chinatown now. I'm not talking about the West Coast. It's totally different over here in New York City's Chinatown. Some of these guys who came out from prison many years later, some of them did their 20, 25 years whatnot.

They came out. Most of them live a quiet life, but they were just a handful would go back into life of crime. Now they know not to call themselves any particular gang name or be a Dai Lou and have like 20 or 30 people. They'll operate in cells like four or five people in a crew. Then they'll link up with another crew to coordinate their business dealings together, whether it's through gambling houses, prostitution houses, or scams that they do credit card fraud. That's what they do-- and drugs.

Kerry: You go out of your way in these videos to say that you don't want to glorify crime, you don't want to glorify violence. Let's drive that point home in the few minutes we have left. What was particularly tragic about the way these gangs operated that is in maybe in danger of being a little bit glorified by the media?

Michael: The movies and the media, they glorify everything. There's so much to talk about. Every newspaper article that I found in the archives, there's a backstory behind it. One day on my channel I'll go to every single article that they have because I have the sources out there to talk about those articles and the story behind the story.

Kerry: As we talk about the racism of anti-Asian hate crimes. What impact can that have on these targeted communities being more vulnerable, or is there a danger that these gangs may rise up as quote-unquote protectors?

Michael: No, because money to the gangs supersedes that. They don't want to draw any attention to themselves. They're not out there protecting the community in Chinatown. Their main goal is to make money. If there's any sort of violence they don't want any attention from law enforcement. They're going to keep continue doing what they're doing, making money.

Kerry: We've got about 30 seconds, but before I let you go, are there any common threads from the testimonies of these former gang members that you've gathered so far? Is there anything that has surprised you or has made you reevaluate the way you thought about your own experiences with the gangs?

Michael: Nothing surprised me. I was in the life for nine years, so I know what they went through because I went through the same struggles.

Kerry: Thank you so much. We've been speaking with Michael Moy. He's a former NYPD detective. A former participant in the gangs in Chinatown, and now the citizen historian behind the YouTube channel, Chinatown Gang Stories. Michael, thank you so much for joining us today.

Michael: Thank you for having me.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.