'The Critic's Daughter' Explores the Marriage of Lynn Nesbit and Richard Gilman

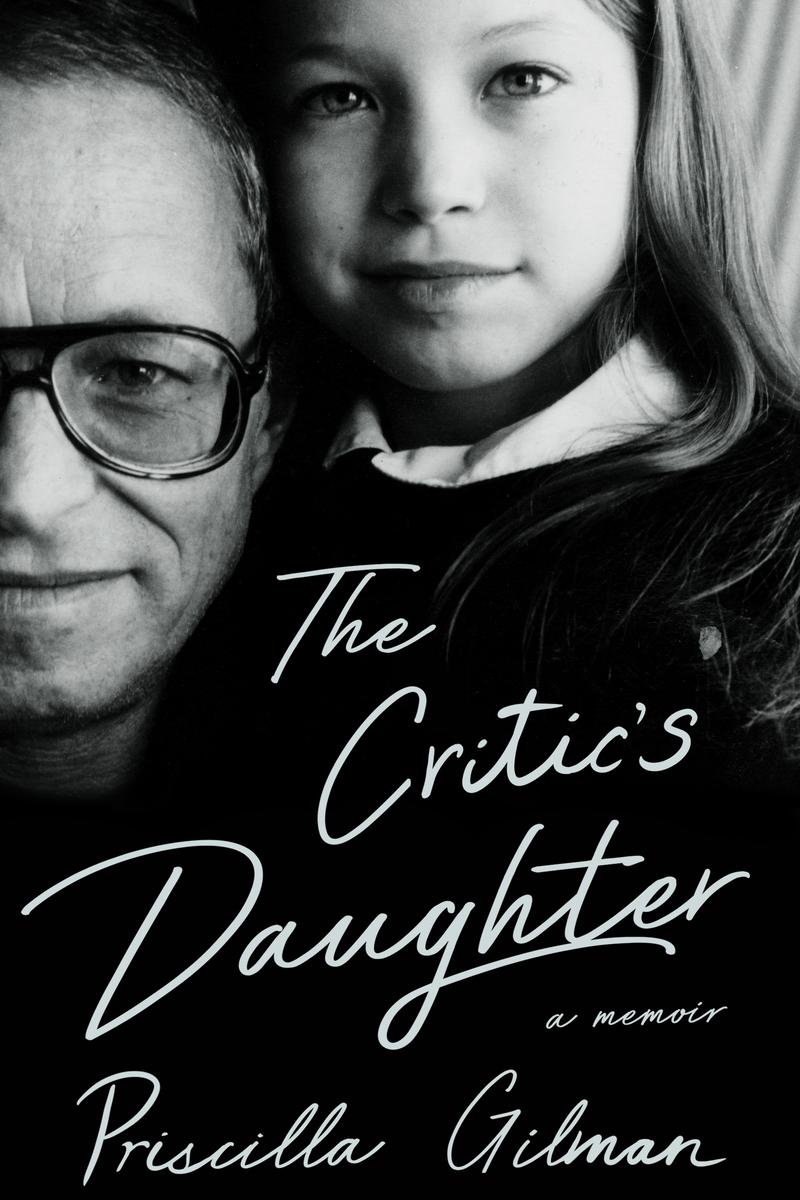

( Courtesy of W. W. Norton & Company )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Priscilla Gilman grew up in a New York City where academics and authors could afford big apartments on the Upper West Side. Her family's was rent-controlled, and as Gilman remembers it, the place had about 10,000 books in it. In the 1970s, as a child, she was surrounded by fierce intellectuals, her parents' friends, who despite their fame or position would still find time to read her a bedtime story. Someone like Aunt Toni, as in Morrison.

Gilman's parents were for a time a literary power couple. Her mother, Lynn Nesbit, was and still is an esteemed literary agent, whose client list is impressive. Toni Morrison, Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, Anne Rice, Robert Caro, to name a few. Gilman's father, Richard, was an author and a big deal drama critic described as a philosopher critic in his New York Times Obituary. He also taught at Yale School of Drama and was the President of Pan America. To Gilman, they were simply mom and dad, until they weren't.

Up until the time she was 10, along with her sister Claire, they were a unit. Dad was more involved in the day-to-day parenting, and mom made the big money. When her parents split, Gilman tried really hard to make everything okay, to keep up her father's spirits as he descended into post-divorce despair and a downward economic trajectory. Priscilla tried to adhere to certain rules her mother had about clothing, and food, and education, but she was just a kid.

As an adult looking back on her family dynamic, she's able to think about her parents in a way that considers them as people, not just her caregivers or kin. She learns about her father's sexual activities, her mother's true love, and she comes to understand how she was choosing unhealthy potential partners. The result is a memoir called The Critic's Daughter. Kirkus Reviews said of the book, it quotes, "Evokes both a uniquely brilliant and troubled man and the poignantly relatable essence of the father-daughter connection." A starred review on Booklist calls it, "A richly involving chronicle gracefully laced with literary allusions, compassion, and wisdom."

Priscilla Gilman is an English professor having taught at Yale and Vassar as well as in public schools and in prisons. Her previous book, The Anti-Romantic Child: A Story of Unexpected Joy, was about raising her special needs son, Benjamin, who has autism. She's still a New Yorker, and she joins me now. Hi, Priscilla.

Priscilla Gilman: Alison, what an introduction. It is so great to be here with you. Always a New Yorker, baby. Always a New Yorker.

Alison Stewart: [laughs] When did you realize that your mom in addition to being your mom was someone that had a certain kind of power in the world?

Priscilla Gilman: My mom, I knew from as early as I can remember, Alison. She went to an office, most of my friend's moms didn't go to offices. She had a secretary, she wore power suits. Everybody wanted her attention, everybody wanted her approval. I knew she was very powerful, but at home, she was just mommy.

Alison Stewart: How about with your father, when did you realize your father had some sort of power?

Priscilla Gilman: My father, yes, he did not have these impressive accouterments, Alison. He did not carry a briefcase, he did not go to an office. He went to Yale, which is a mysterious space that I never visited, but I knew that my dad had authority. He had intellectual authority, he had cultural authority. I knew that all of their friends wanted his approval. They wanted him to like their work, they wanted him to approve of their ideas.

Alison Stewart: I'd love you to read a little bit about your dad from page 10 of your memoir, The Critic's Daughter.

Priscilla Gilman: Oh, sure. This is a quotation from a 1970 New York Times article. That was the year I was born, and he's talking to them about directing a play at the old repertory theater. He says, "I don’t think of myself as a critic or teacher either, but simply, and at the obvious risk of disingenuousness, as someone who teaches, writes drama criticism, and other things, and feels that the American compulsion to take your identity from your profession with its corollary of only one trade to a practitioner may be a convenience to society, but is burdensome and constricting to yourself.

Despite my father's aversion to being categorized as a critic or teacher," and I didn't question the title of my book for a minute when I found this part, Alison, "He'd been the theater critic at Commonweal and Newsweek and taught at Yale Drama School from 1967 to 1997. He indisputably was a certain kind of New Yorker in the 1970s. Liberal, passionate, intellectual, clad in denim shirts or turtleneck sweaters, bell bottom jeans or corduroys, sneakers or Wallabees. A pack of cigarettes bulging out of one pocket or another, with black clunky glasses, and wild curly hair. My father cut a dashing, yet unpretentious figure.

He was, as at ease discussing the travails of the New York Giants as he was debating the merits of the latest Éric Rohmer film. He loved classic New York deli food, Chinese takeout, pizza. He shopped at Zabar's, Barney Greengrass, H&H Bagels, and the local mom-and-pop stores in our Upper West Side neighborhood. He had next to no vanity about his appearance. Bought cheap sneakers and jeans at an outlet store on Broadway, had his haircut by our neighborhood barber, and exercised only when my mother cajoled him into playing doubles tennis with friends.

He loved New York City's independent and used bookstores, its libraries, zoos, and museums, Central Park, where he pushed and my 14 months younger sister Claire on precarious metal swings, bought us soft pretzels, and chased us up and down the rocks. Riverside Park, where he watched us zoom down slides and run through sprinklers. His idea of a great evening would include a poker game with cigar-smoking buddies, a spirited discussion of a novel or play, and reading aloud to his daughters."

Alison Stewart: That's Priscilla Gilman reading from her memoir, The Critic's Daughter. How would you say your parents parenting philosophy differed? What was the biggest chasm, and then how was it very similar? What was something they both believed in?

Priscilla Gilman: They really shared parenting values in most ways. I would say the biggest chasm as I got older was that my mother was much more open to us loving the Go-Go's and Men at Work, and going out with boys and all of that. My father did not want any of that. I think that thing that they shared more than anything else was that the arts were central to a valuable and happy human life and that they encouraged me and my sister to read and do well in school, not just to get the good grades, but to become complicated, and interesting, intellectual people. They encouraged us to see all the movies and read the books, classic books, and they really believed in literature with a capital L.

Alison Stewart: A large part of the book deals with your parent's divorce. Now, looking back, what do you understand about why your parents divorced? As an adult, can you see that it probably was the right move?

Priscilla Gilman: Alison, 100%. It was so the right move. They probably never should have been married, although they did produce two interesting kids, so it's good that they were. My mother was never in love with my father. She had had her heart broken, and you can read the book to find out who broke her heart and how, in a pretty horrible way. I think she married my father because she thought he was brilliant, and she respected him greatly, and she knew he would be a good father because he had had a son from a previous marriage and she saw him as a father with his son.

I think that the split was necessary for both of them, even though my father, he plummeted into despair, and as you've said, went through some financial travails. He was very much in love with my mother and very heartbroken. He ended up meeting the true love of his life. I think they both were better off as people in their personal and professional lives, actually, after they split.

Alison Stewart: As I was reading the book, I thought about something, and then you wrote it in the book that-

Priscilla Gilman: Oh, I love that.

Alison Stewart: -you and we are part of the Kramer vs. Kramer generation.

Priscilla Gilman: Oh, yes.

Alison Stewart: When a divorce might happen because the woman was not feeling fulfilled, and that's it, full stop. You also mentioned, at the time, feeling some shame about your father's vulnerability, as you put it, and your mother's aggressive power. Let's think about each one. What was it about your father's vulnerability that was either frightening to you or made you feel the shame?

Priscilla Gilman: His vulnerability, I know he did say to me shortly after my mother announced that she wanted to split up, he did say that sometimes he thought he would kill himself if it were not for me and my sister.

Alison Stewart: That's a lot to say to a kid.

Priscilla Gilman: That is a lot. It was scoured on my brain, Alison, and it became a mantra, like, "My father's survival is my responsibility and I need to cheer him up. When I see that he's about to cry or I see that he's getting irritable, I have to manage his moods." It was a huge responsibility. I feel the shame came more from my father not being like other fathers, in that most of the fathers in my school, they were married.

My parents were one of the first amongst my friend group to get divorced. My father being so financially unstable, not having a home that we could stay over in, and being an intellectual really, going into the '80s when New York City started to get very expensive, very hard to live in for intellectuals. That's why I loved how you started, in the 1970s, we could afford these wonderful apartments on classic sevens on Central Park West, yes.

Alison Stewart: How about for your mom, your mom's aggressive powers, how you wrote it?

Priscilla Gilman: I think I saw my father as so vulnerable to my mother. He so wanted her to love him. He so wanted her to approve of him. He really revered my mother. It felt like there was something off in the dynamic. He was too unfortunate, he was too pleading with her, and she was too chilly and cold to him. It's interesting, a couple of reviews of the book have described her as chilly. I don't think I depict her as chilly per se. She was chilly because she was in an extremely unsatisfying marriage that she was trying to extricate from. To do that, sometimes you have to shut down that empathetic part of yourself and become cold to get out, which she needed to do.

Alison Stewart: As you mentioned, you were a pleaser, trying to fix things, writing your dad notes like, "I'm thinking of you and I love you." It was interesting because your sister on the other hand never had a problem letting it known how she was feeling, at all. I thought it was weird because you grew up in the same household and you're very close in age. What do you attribute that difference to?

Priscilla Gilman: It's so interesting. I so admired my sister's ability to just voice her needs and her concerns and say, "I don't want this food," or "I've got to pee, you got to stop the car." I wouldn't do that. I think kids come out the way they're going to be. I've seen that with my own two children who are so different. I think that we also got hardened in those roles, though, by our parents because they assigned me the role of the mature, older, smiley, good girl, and they assigned my sister the role of the vulnerable little cub who is in need of protection from the world. My sister and I still say to each other, we're like, "We're 14 months apart. This is crazy. We're basically twins."

Alison Stewart: My guest is Priscilla Gilman. The name of the book is The Critic's Daughter. We'll have more with Priscilla after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It, I'm Allison Stewart. My guest this hour is writer and professor Priscilla Gilman. She's written a memoir about her life growing up in New York City as the daughter of a literary power couple who divorced when she was a child and whose legacy she's reexamined over time. It's called The Critic's Daughter. Priscilla, even though your dad loved you and he was a critic, he did say he would never tell you something was good if it weren't good, that he would not lie to you about that. Why was that valuable?

Priscilla Gilman: Oh, it was so valuable and I use it in my teaching, Alison. I will never tell my student that their work is good if it isn't because I think in order to really trust someone, especially somebody in a position of power, pedagogical power, I always want the truth. I want them to say, "There's a baseline of respect, there's a baseline of admiration for your brain, I know you can do better, this isn't it. Let's try again."

Alison Stewart: There are a lot of revelations in the book, details about why your parents, super agent Lynn Nesbit and theater critic Richard Gilman, you learned they were sexually incompatible, that there was a shaky foundation of the marriage from the very, very beginning. As you worked on this project, when and how did you decide what to include and what not to include? Because you go there in a couple of chapters.

Priscilla Gilman: I definitely go there, Alison, and I knew I had to go there. If I was going to write this book, if I was going to be true to the spirit of my father, I had to tell the truth and I had to not shy away from the tough things and the hard things. There was one detail about the letter that I found when I was 10, where he talked about wanting to be dominated by his ex-wife. I was nervous about that, and my editor said to me, "You've got to include it, you've got to put it in. Your father would want you to."

Alison Stewart: Why would your father have wanted you to?

Priscilla Gilman: He wrote a memoir that came out in 1986 called Faith, Sex, Mystery, where he discussed his BDSM tendencies. He was going to write another memoir where he talked more about his sexuality, and he was not able to publish that because he got terminal cancer. I feel that even though some of the details in that letter were not things that he included in his memoir, I wrote the book in a sense to diminish any residual shame that my father or anyone like my father might feel about their sexual makeup, about the fact that he suffered from depression.

In many ways, I think that my father lived too soon. I think that today he'd have a million websites he could go to where he could find someone who would do exactly what he wanted to do. I just felt so much empathy for him coming of the age as a man in the 40s and 50s and feeling so different and so unusual and having to hide all of that from his parents, his wives, et cetera.

Alison Stewart: You have a remarkable memory for detail.

Priscilla Gilman: I do.

Alison Stewart: As a child, did you keep journals? Is that just how you're made?

Priscilla Gilman: Alison, it's just how I'm made. I had a few journals. There's that journal where I find that thing that I wrote about things not to do when I'm with daddy and [inaudible 00:15:13] but in general, you can ask any of my friends from all the way through, I can tell you what they wore to the first-grade play or who they played in the seventh-grade, Gilbert and Sullivan production. It served me very well as a memoirist to have this memory.

Alison Stewart: What's changed about you since you began to consider your father as not just dad, but your father as a person living in the world and your mother as a person living in the world?

Priscilla Gilman: Alison, I love the way you describe that in the intro. That's exactly what I'm trying to do with this book, is to see both of my parents in all of their complexity as humans with their own struggles, their own pain, their own shame, and to depict them in all of their messy humanity as a gesture, I hope, of anything that I had to forgive them for. I really didn't have resentment towards either of them, but really wanting to honor them and to see them as human beings separate from me. It's helped me as a mother with my own children to be a little more forgiving of my own mistakes because all parents make mistakes and all parents bring their own stuff to their parenting.

I think it's helped me in that way as a mother. It's also helped me, I hope, make better romantic choices going forward. You mentioned that and that's absolutely something I got patterned to choose men who were very needy, depressed, and wanted me to save them. That was attractive to me, and now it's a red flag if I start to see that.

Alison Stewart: It was interesting reading some of the coverage of the book because some think you're really unsparing about your mom and easy on your dad and something vice versa. Some see you as very even-handed. Have you figured out what it is that people are seeing that tilt them one way or the other?

Priscilla Gilman: That's such a good question. It is a book about my father and it's not a book about their marriage. It's not a book that's meant to be equally about my parents. I've had some people ask me to write a book about my mom and my mom's like, "That's a no." I think the people who think I don't do enough on my mom, it didn't click for them that it's not meant to be a full portrait of my mom in the way that it is about my dad. I think that there's some-- I don't know. Some people read my depiction of her as critical when it's just factual. In other words, she didn't want to play with us when we were little. I wasn't upset about that.

I learned from a very early age some people are better at some things, some people are better at other things. In The Anti-Romantic Child, I talk about how she's sort of the ideal grandparent for my son with autism because he doesn't want to play imaginatively and she'll throw a ball with him for hours or read to him. I think we all have our strengths and our challenges as parents, and I don't judge my mother for not being like my dad. They both came to me and they both gave me so much. I'm a complicated mix of both of my parents.

Alison Stewart: Also, when you said your dad may have been before his time, I think your mom might have been before her time as well, some of the things that-

Priscilla Gilman: Oh, so much, Alison. It's incredible to me. It's amazing. She moved to the Midwest from this tiny town, the first person to graduate from college on that side of the family, comes to New York, lives with four other girls in the village, gets a job as a secretary at a women's magazine. A medical student named Michael Creighton sends her a manuscript and the rest is history. She was struggling against huge, huge odds, and she had to be tough in the world in order to survive and succeed.

Alison Stewart: Maybe she'll let you write a book about her someday. I'd read that one too. The name of the book is The Critic's Daughter, it is by Priscilla Gilman. Priscilla, thank you for so much time today.

Priscilla Gilman: Oh, thank you so much, Alison. My favorite show.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.