A Candid Look at Rock Hudson's Private Life

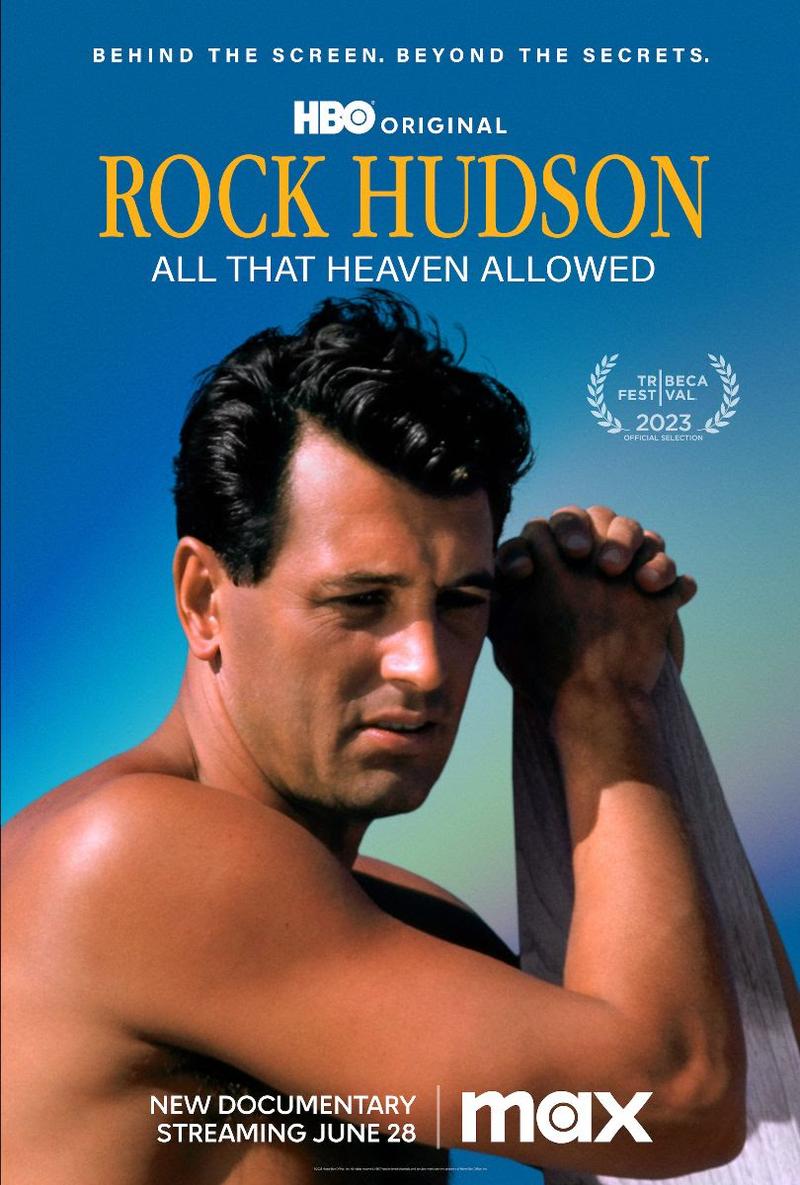

( Courtesy HBO )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. Coming up later in the week, author Maureen Ryan, Mo Ryan. She spent two years researching her book on the entertainment industry's corrosive culture. She'll join us to discuss Burn It Down: Power, Complicity, and a Call for Change in Hollywood. That is in the future, but this hour, let's get it started with a look at Hollywood culture of a different era when Rock Hudson was one of the country's most popular movie stars.

We're continuing our coverage of this year's Tribeca Festival. The in-person events run through June 18th, and it's going to spotlight and celebrate some great new films, TV series, and podcasts. Once the live events end, there's Tribeca at home, a virtual version that's from June 19th to July 2nd. We realize that's a really long time, so we're calling our coverage this year.

Speaker: Tribeca-thon.

Alison Stewart: So cheesy, but I love it. Today for Tribeca-thon, a documentary about Golden Age Hollywood heartthrob Rock Hudson. The film highlights the tension between his cultivated image and all American romantic man's man, and his private life where he was a very different type of man's man in that he liked men a lot. This was a time when homosexuality was considered a disease, in some places a crime, and when the FBI was interested in who was gay and who was not.

The documentary takes a look at Hudson's onscreen career and places some of those performances in conversation with the real story of the actor's life. A review on the site, The Playlist, notes that this juxtaposition works because the director "understands that the movies weren't just what Hudson did but what he was." He was an icon and a history-maker. In 1984, after Rock Hudson was diagnosed with HIV, he was the first major celebrity to publicly acknowledge his infection.

The film attributes his disclosure with an influx of fundraising and research efforts at a critical point in the AIDS crisis. That's why the documentary was almost called The Accidental Activist, the title of the documentary wound up being Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed are reference to a 1955 film he starred in. It premiered yesterday evening, and it's showing again tonight, and another screening next Saturday. You can check out times and ticket information at tribecafilm.com. Joining me now to talk about Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed is director Stephen Kijak. Stephen, welcome to the studio.

Stephen Kijak: Hey, thank you. Good to be here.

Alison Stewart: When did you get interested in a film about Rock Hudson?

Stephen Kijak: Well, when my producer called me and said, "Do you want to make a film about Rock Hudson?" I was like, "Yes, please." It was just a producing team I worked with for a long time, and it just presented itself as a great subject to dig into. I'd been looking to do more stuff in the LGBTQ space, history, pop culture, movies. It just had it all. I think it was a really important story.

Alison Stewart: What did you know of Rock Hudson before this all started?

Stephen Kijak: Not much. I had seen a bunch of the films. I think I had been more interested in the great directors he worked with like Douglas Sirk, or Frankenheimer, Seconds, was a favorite film. I was just more interested in the movies he had been in and I didn't really know all that much about him. Little journey of discovery for me and my audience. It was great.

Alison Stewart: Why did you land on the title All That Heaven Allowed?

Stephen Kijak: I thought the Accidental Activist, while accurate, was a little limiting. I didn't want to in any way disrespect the actual activists who were on the front lines of the AIDS crisis and doing the actual boots-on-the-ground work, putting their lives on the line for the cause. Accidental was 100% accurate. He really maybe was not even aware of the disclosure.

We're not really sure where his head was at at that time, but all that happened a lot. It's one of the best of the movies. It's a sweeping, weird, gorgeous melodrama, one of his best performances, and just hints at a larger story. We actually do get into a lot of his life that could have been, a lot of the lost loves and the hidden self. He had as much as was allowed for him to have before it all came to a tragic end.

Alison Stewart: Let's give people a little bit of context. There was this huge gap between his public image in screen and in the tabloids, which to your point you make in the film is that the studios really controlled everything. They controlled people, in a helpful way, what they ate, their housing, who their friends would be, who they might be dating,

Stephen Kijak: Their names.

Alison Stewart: Their names. Rock Hudson.

Stephen Kijak: Rock Hudson Born Roy Shearer Jr. then was adopted by a man named Fitzgerald, so he became Roy Fitzgerald and dubbed Rock Hudson by his sleazy agent, Henry Wilson

Alison Stewart: We'll get to Henry in a minute. Something I found so interesting in the film was that while there was this crafted image of him as hyper-heterosexual, he had a very robust unequivocally gay private life. At the time when he was starting out, how was Hollywood thinking about public personas versus private personas?

Stephen Kijak: It's interesting. There was a time pre-World War II in a way when speakeasy culture was all the rage and a lot of the clubs and bars were mixed. People thought it was cool to go see drag queens and see same-sex couples dancing with each other. It was a little bit more of a lush underworld in a way. Then you move into the post-war era, then McCarthy shows up, and culture chills again. There's this cooling off, there's paranoia. Gays are associated with communism, and it's just dangerous to be gay.

The raids start happening and everything gets shut down. Of course, the studios go on lock. The Hays Code comes into play. There's censorship in the movies, and more and more the publicity machines are just crafting this fantasy world in the press that portrays everybody as heterosexual, looking for love in relationship. The movie magazines at the time was amazing. We had boxes and boxes, these crazy old magazines, and there's nothing about the movies and these movie magazines. It's just all about people's love lives, and I'm guessing 90% of it was crap. It's all made up. It's just fantasy stuff.

Alison Stewart: I want to talk a little bit about the filmmaking and then we'll do some more about the biography of Rock Hudson. You use some of his on-screen performances, and they dovetail-- the dialogue from the performances dovetail with what's actually going on in his life. When did that become clear to you that that was going to be a device you could use that would become available to you?

Stephen Kijak: I always wanted to do it. There is a brilliant essay film from the '80s called Rock Hudson's Home Movies by a filmmaker named Mark Rappaport that almost is exclusively about the double entendre hidden codes in the movies that show you that, look, this man lived a gay life and we can piece it together using his own movies. It really highlighted all that stuff and made up some too, but it makes a great case. It's been a little bit forgotten, maybe hard to find, but I've always loved it, and I thought this is a great way forward.

Not only did I want to highlight some of that stuff, which is fantastic, but to get the films in conversation with each other. The real idea was essentially to try to let Rock just be a gay guy and flirt with other men and live as a gay man in a cinematic space from the '50s and '60s, to create this-- we call them little queer cuts where we would have him cruising someone across another movie. It's a little cheeky, but it was very intentional. It wasn't just done for a laugh. We wanted to say, look, here's a parallel universe in which maybe we could have portrayed ourselves on screen at that time and been free to be ourselves.

Alison Stewart: What's an example of one of those double entendres that you were able to use in the film?

Stephen Kijak: The double entendres are hilarious. Like there comes a point in the '60s where it almost seems like everyone is in on the secret and they're using it for maximum effect. He was in an absolutely awful film with Leslie Carone called a Very Special Favor. The famous scene where he's hiding in her bedroom and she comes home and he pops out of the bedroom closet and she says, "Hiding in closets isn't going to cure you." It's such a cheap shot.

Like the Doris Day films, Pillow Talk, is a classic example where his character, who was a virile straight man, womanizer, has got seven girlfriends, shares a party line with Doris Day, and he falls in love with her without knowing who she is at first. Of course, then the trick, the tactic is this mistaken identity thing where she doesn't know what he looks like, but he's going to try to seduce her by pretending to be a gay man so that she can cure him. It's so stupid. He's got the raised pinky, and he puts on a different voice. It's crazy how blatant and obvious the trick was but it worked. It was a huge success. People were still none the wiser.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Stephen Kijak. He is the director of the documentary, Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed. It is screening at the Tribeca Festival. At the beginning of his career, he was getting cast in roles that really didn't take advantage of his sense of nuance or his sense of, I can be a subtle actor. I'm not just this big hulking, handsome hunk of man. What were some of the roles he played where people started to notice that he had talent?

Stephen Kijak: Interesting question. I would say there were a lot of stinkers. He was a studio system grunt. He was under contract, and he had to do whatever they told him to do. Films like The Scarlet Angel or Gun Fury, I think it was a Raoul Walsh. They're broad adventure western films, mostly bad, but the further along you get, you start seeing that he's a commanding presence. It's almost less that they saw a great actor in him, and they just started seeing the piles of fan mail and went, "Oh, we've got something here. Put him in bigger roles. Give him more leads."

He wasn't a trained actor. He learned everything he knew at Universal. It was a time when they would sign you on your hunky good looks, and then put you to work or put you to school, really, take you to school and train you at the studio in all the aspects of the art. He got his training on the job from crummy background parts and small speaking roles. You just see it over like 60-plus movies, and that he eventually gets his big break with Douglas Sirk in Magnificent Obsession.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk about Douglas Sirk, the German director. He did nine movies with him, something [unintelligible 00:11:47]?

Stephen Kijak: I'd have to go back and check. A bunch. They did a good handful.

Alison Stewart: A bunch. What was it about this pairing that worked?

Stephen Kijak: Father figure stuff. I think like Rock's parents divorced when he was young. He did not have a great relationship with dad. We don't really explore this much in the film, but he did his best with very strong, caring, nurturing father-figure directors. Sirk, Raoul Walsh spread out the best in him, then later George Stevens with Giant.

I think Sirk was an older man, just very kind and generous director, and really gave him the room to explore his character and just to do his best work. He was just a very nurturing director. Sirk is coming from the German Expressionism School, his films are nutty melodramas. He admitted these are crappy scripts, they're just terrible, but like, "Hmm, I can see a way to elevate this with lighting and style and costume."

In a way, some people may think the characters in his films are just little puppets, and he's very manipulative and it's really artificial, but they are flesh and blood characters brought to life by these great actors. Rock is-- you just can't take your eyes off him in these films. Can't take your eyes off his hair in these films. [laughter] Like the quiff is awesome. The pressed flannels. They're just stylistic marvels.

Alison Stewart: He's so handsome.

Stephen Kijak: Yes. He was at his feet in those films, you can't believe it.

Alison Stewart: Truly, just such a handsome man. We're talking about the documentary, Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed. It's screening at Tribeca. I'm speaking with it's director, Stephen Kijak. Let's get to Henry Wilson, the agent, what was the word you used?

Stephen Kijak: Oh gosh, I've already forgotten.

Alison Stewart: Sleazy?

Stephen Kijak: Sleazy, Stevy, Lascivious.

Alison Stewart: He became integral, we'll say, to Rock Hudson's life. How did they meet? What was Wilson's process of taking on actors?

Stephen Kijak: There's a number of stories about how they actually met, but I think we've decided the most accurate is that Rock was at a party with Ken Hodge, who was a young man he was in a relationship with, who was a radio executive who was trying to help Rock with his Hollywood connections. He just meets Henry Willson at a party, and Henry Willson's, the Power agent, works for David O. Selznick. He's not an attractive man by any stretch, but Rock is very ambitious, and he's like, "Well, who am I going to leave the party with?" This radio producer or the biggest casting director in Hollywood, bam.

I think Rock was very shrewd and hooking up with Henry, and Henry just saw the opportunity to craft. Rock is like his greatest creation. Word has it that it was Henry who named him a combination of Rock of Gibraltar, Hudson River. He couldn't pick more butch iconography to put together. Henry groomed these guys, taught them how to dress. There were a lot of these guys who was hicks or coming off of the military, and good-looking and thought, "Let me just try to maybe try to make it in Hollywood."

If your sexuality was somewhat fluid or you were really just desperate for a big break, Henry would have sex with you and trade X-rated favors for casting calls and meetings with producers and stuff. Typical like Robert Hoffler, who wrote the book on Willson, it's a great book. Calls him the manizer, like there were womanizers, but Henry was a manizer. One of the most notorious in Hollywood, and everybody knew it. He had this amazing stable of guys with nutty made-up names. He gave us Tab Hunter, for example, Race Gentry. He tried to crack a guy with the name Chance Nesbitt. That didn't quite work out, but Henry had his ways.

Alison Stewart: Two syllables, Nesbitt. That's where he went wrong. We get to a part in the documentary where Rock Hudson marries. There are all these in those movie tabloid magazines. Rock Hudson still single, what's going on there? He marries Henry Wilson's secretary, I believe it is.

Stephen Kijak: Phyllis Gates, Henry's secretary.

Alison Stewart: Did Henry Willson orchestrate this?

Stephen Kijak: 100%. Oh, yes, 100%. I think we--

Alison Stewart: Did Phyllis know? That was a question of the documentary, was that clear whether she knew or not?

Stephen Kijak: Oh, she knew. She knew. It was a totally arranged situation. She was the film says-- we said like she was most likely bi or gay herself. Hoffler in the Willson biography goes even further and says she was 100% a lesbian, and she actually was a notorious blackmailer of women and a real piece of work. A lot of other people-- I don't know, there's a lot about these stories that are really hard to verify, but by all accounts.

In a way, the two of them, Rock and Phyllis were pals. A lot of people said, "Oh, they had great fun together." You'd almost think they were in love. They had a good laugh, they really enjoyed each other's company. Then the situation of the arranged marriage, I think, put a real-- really screwed it up. Then she seems to have really taken on the role of Mrs. Rock Hudson a little too seriously. Didn't really want him to be the man about town that he was known to be. It only lasted about three years.

Alison Stewart: She ended up financially secure as a result.

Stephen Kijak: Yes, he had to sell a boat that he liked, and she would often-- We've found a bunch. She would send him her department store invoices and expect him to just keep paying for them. She was a pain, poor thing, but it did the trick for a while.

Alison Stewart: Why couldn't he just be a bachelor?

Stephen Kijak: You just couldn't be a bachelor.If you were 30 and unmarried, you were gay. Clearly, something's wrong with you. It was one thing for Tabloids to ask these questions, but the real problem was when he was on the cover of Life Magazine was they were about to release Giant. Even Life Magazine is going, "Why doesn't Rock Hudson have a husband? Why doesn't he have a husband? He should have a husband. Why doesn't he have a wife?" It was like, now Life Magazine was asking the question and everyone thought, "Mmh, we need to get him married and get this out of the way so we can keep making money with him and maintain the image."

Alison Stewart: We're talking about the documentary, Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed. It is playing at Tribeca. I'm speaking with this director, Stephen Kijak. You have a lot of his friends in the film talking about him. What impression did they give you about what kind of friend Rock Hudson was?

Stephen Kijak: Almost two or one. He was a very kind, generous, wonderful guy. He was very well-liked by the press. His friends all say he was just an actual decent, wonderful man, and very generous. There are lots of stories of him helping people in need. He'd go the extra mile to help a friend, just would do crazy thing.

I think Robert Stack and him were in a-- I think it was the making of the Tarnished Angels, and Robert Stack had to be on set while he was having a child. Rock hired a plane to buzz by with a big banner that said, it's a boy. You know what I mean? Just little anecdotes like that just keep cropping up about how thoughtful he was. Someone at one point was like, "If you could describe Rock Hudson in one word, what would it be?" They went, "Christmas." That was just his personality.

Alison Stewart: He also liked to party.

Stephen Kijak: He liked to party.

Alison Stewart: What's the best Rock Hudson party story you heard from his friends?

Stephen Kijak: There wouldn't be necessarily one specific. It was just if I could only have been a fly in the wall-- more than a fly in the wall at the famous pool parties. This was like that era, right? I know, like George Cucor was famous for these all boy pool parties. I think his would be like on Sunday and Rock would have them on Saturday or something. There was just the gay Hollywood elite tucked away in the hills of these private estates just would throw these mind-blowing parties with every piece of eye candy they could get their hands on. It was just a different time.

Alison Stewart: How did his friends talk about him balancing that life of living authentically and having a great time at these pool parties with what he had to sell to the rest of the world?

Stephen Kijak: It's interesting. I think, at certain points in his life, he could express himself and live with a little more of a degree of freedom. I think the older he got, he did tend to maybe close down a little bit. Although, I say that, but then he would go to San-- and this thing, he would go to San Francisco, which was just a little bit outside of LA, and that wasn't Hollywood, so he could live a lot freer. There just was a lot less scrutiny. Just a lot less scrutiny, which is why he could have this open secret and enjoy his gay life in somewhat private Circumstances.

The partying was at home, the dinners were at home. He'd go to Laguna, to friends houses. It wasn't like they were outraging at the gay bars or going to Cabarets. He wasn't very public, but everything was done behind closed doors in a way. Then flash forward to the '70s, he's a big star on McMillan & Wife on television. Our little friend, Ken Malley, in the film, who was a big publicist and key figure in San Francisco media, would take him out to the glory holes, and they would just have a grand old time, and he just didn't seem to care very much.

Alison Stewart: When did J. Edgar Hoover begin to be interested in Rock Hudson and why?

Stephen Kijak: This was a whole period of the Lavender scare, coming off of the McCarthy Craziness and the purges in Hollywood, the Blacklisting and all that, communism. Then people are assuming homosexuals are easy targets for Blackmail, hence the communists will get them and use them against the US government. It was that like late '50s period, but everybody had a file. Burt Lancaster has to had a file, because apparently, Burt and Rock wrote some enormous gay orgy in the hills.

Burt apparently was an omnisexual. He wasn't really-- you know what I mean? Anything that moved, but they would just keep tabs on everybody. They never went anywhere. It's just unbelievable that they had informants, they had sources, he would be followed. They observed him going to known gay places, and had a lot of evidence of people that would squeal, that they'd actually have sex with Rock Hudson and go squeal to the FBI.

The file was pretty extensive, but nothing ever happened. You found this a lot in those days, a lot of the closeted celebrities or even the gay activists. We've done a lot of work in that space, and it's always fascinating to go through the FBI files. They're voluminous. There's so many of them. You just think, what a waste of time. [chuckles] So much paperwork. It doesn't really reveal much aside from the fact that people were keeping an eye on you.

Alison Stewart: We're talking about the documentary, Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed. I'm speaking with its director, Stephen Kijak. It's part of the Tribeca Festival. We get to 1984. He's diagnosed with HIV, and this is, obviously, at a point in the epidemic where fewer than 10,000 people have died of AIDS, but it's about to be in the crisis point. I remember the '80s quite well. How did he react to the news of his infection?

Stephen Kijak: Massive denial. He was in massive denial. We have the benefit of having George Nader's diaries. George Nader was a fellow actor who didn't go on to have a massive career, but George had a long term partner, Mark Miller, who was then Rock's secretary. George kept meticulous diaries, very crucially right at that time. The day Rock goes to the doctor and is told you have AIDS. What you see-- there was just a lot of it, to--

Alison Stewart: My guest is Stephen Kijak. The name of the documentary is Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed. It's really heartbreaking that how isolated he became, that his very good friend Nancy Reagan wouldn't even intervene in any way and wouldn't talk to the White House about it. I just found that to be-- It was just heartbreaking.

Stephen Kijak: It's heartbreaking, but not hard to believe.

Alison Stewart: Yes, we thought.

Stephen Kijak: He was in denial, they were in denial. The administration just refused to engage with the disease at the time. Literally, their response was, "Well, if we help him, we'll have to help everybody. Lord forbid." It took him dying for them to wake up. How long into the epidemic did it take for Reagan to even say the word AIDS? It was a long time. I'm now forgetting the actual date. I should know this off the top of my head, but it was well past '85, and it was a conflagration at that point. It was such a public health crisis.

Yes, I just wasn't surprised at all. They have so much blood on their hands for ignoring it. What Rock did or not necessarily that he did intentionally, but by the fact that now the world knows Rock Hudson, this paragon of heterosexuality, not only is a gay man, but that he has AIDS. That's what we really explore in that second half of the film is how crucial it was to change the conversation and elevate it into the mainstream. Whether that alone or that amongst all the other pressure that was being put on the administration finally forced their hand to increase funding, to start changing the tone of their discourse around it. A lot of the activists we talked to said it 100% helped and had a massive impact.

Alison Stewart: Throughout the film, we see his friend, the writer Armistead Maupin, pushing him to come out of the closet to disclose a diagnosis because of how much it would help the cause of gay rights and his fellow citizens. Is there any sense that he ever expressed wanting to be a part of the gay movement, of the gay rights movement, of advocacy?

Stephen Kijak: Never. No. It's really interesting. It's so generational. Armistead, I think-- obviously younger generation, the forefront of being out and proud, that generation that was pushing for gay liberation. He says in the film, like, "Oh, Rock listened." When he said, "Come on, I can help you come out. I'm skilled at this. I'm a journalist, I'm a writer. We can do this in a way that's going to make a difference." He said he didn't have any real interest in doing it. That whole generation, Rock, producer Ross Hunter, who was responsible for pillow talk and all that heaven allows and all that.

Ross Hunter is an interesting character. You see him at the end of the movie after Rock had died, and he's very emotional, saying, "He was my best friend. We grew up in this business together." Even after Rock died, Ross wouldn't even admit that Rock was gay. He kept his secret out of some weird sense of loyalty that I believe some men of that generation considered their duty. That we're going to keep this secret, we're going to protect our private lives. It doesn't really matter. It's not going to change anything if people know. They were just caught in that changing social attitude.

Alison Stewart: Did you find anybody who didn't want to talk to you about this [crosstalk]?

Stephen Kijak: I got to say, almost-- There's a lot of people who aren't with us anymore. A few people who-- I don't know, and it wasn't for anything major. It was more just like, "Oh, it was just really a private time, and what we had was just for us." I never found anyone that was just adamantly refused to speak. Everyone that we did talk to was really generous with their time and their memories. I found it really touching, like, meeting a lot of these guys.

The interviews we do do for the most part, we have a very specific choice of men who will take you from the pre-liberation, pre-Stonewall era. One of Rock's boyfriends from '63, for example. Friends and pals from those days all the way to the other side of the AIDS crisis. Men who lived through it and HIV positive and surviving, but who were in Rock's life in some way and who were affected by him. Lives changed, careers changed. It was really touching to craft the portrait of that generation.

Alison Stewart: Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed, premiered yesterday evening at Tribeca. It's showing again tonight with another screening next Saturday. You can check out times and ticket info at tribecafilm.com and it will be streaming on the HBO streaming, so it's Max starting on June 28th. Its Director, Stephen Kijak, has been with us in the studio. Thanks for being here.

Stephen Kijak: Thank you so much.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.