The Bronx Museum of the Arts Celebrates Hip-Hop's Origins in its Backyard

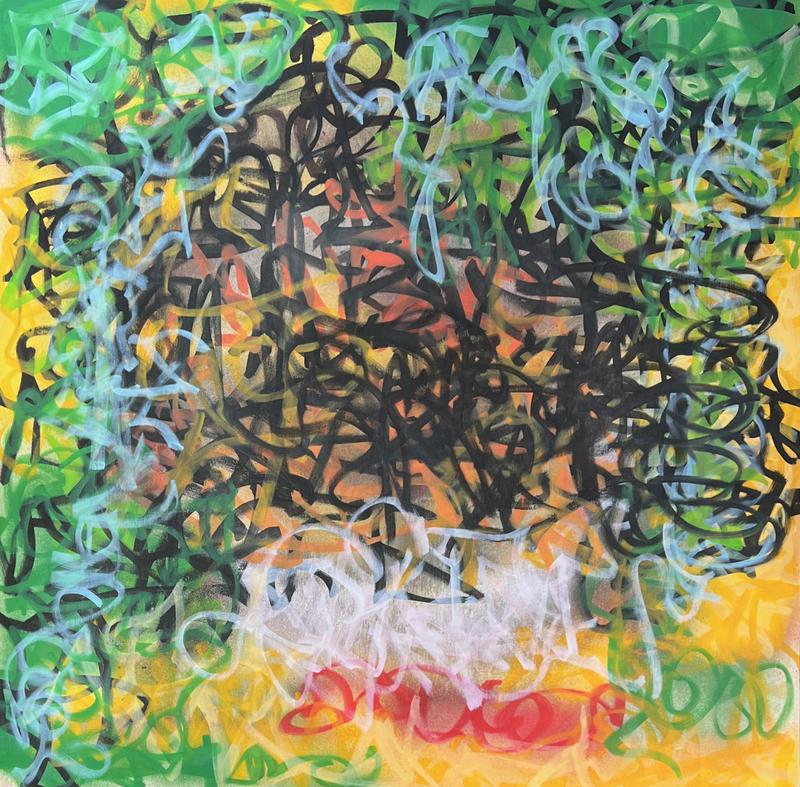

( Courtesy of Dianne Smith )

Announcer: Listener-supported, WNYC studios.

[music]

Arun Venugopal: This is All Of It. I'm Arun Venugopal, in for Alison Stewart. The Bronx Museum of the Arts is celebrating the 50th anniversary of the music first created in its home borough with an artist from its home borough, Dianne Smith. Two Turntables & a Microphone is both a celebration of hip-hop's anniversary, but also the work of artist, Dianne Smith, who was born in the Bronx and came of age during the rise of hip-hop in the 1970s and '80s.

She was front and center in the culture. In fact, she was even classmates with Slick Rick and DJ Dana Dane while attending LaGuardia High School. There's memories, other archival pieces, and new work commemorating the Bronx and hip-hop's 50th anniversary, are the subjects of this exhibition, which is on view at the Bronx Museum of the Arts through August 20th. Artist Dianne Smith will be joining us, hopefully, but right now we have the curator of the show, Souleo. Hi, Souleo.

Souleo: Hi, how are you today?

Arun Venugopal: Great. Thanks for joining us. Hopefully, we'll have Dianne any minute now. There's some technical issues. Tell us, from a curator's perspective, putting on the show, there's so many angles you could find for something as momentous as the 50th anniversary of hip-hop. Why did you pick this particular weigh-in?

Souleo: I know it was very important for Dianne to come from a personal perspective as well as the communal focus. We started with her archives. As you mentioned, she went to school with Slick Rick, Dana Dane, and other members of the Kangol Crew, and she had these amazing photos from that era. That was really the starting point. Then in having conversations with her, it became very clear what that time meant to her.

It was about community. It was about creativity. It was about the joy of hip-hop. In the 50th anniversary, it was really important for both of us to really get back to some of those values that may have been lost. As hip-hop has become more mainstream, we can lose focus of what the music actually does as a community-building tool. That's where we started.

Arun Venugopal: Really back to the roots, as you say, with a title like Two Turntables & a Microphone. How did you come up with that title?

Souleo: I was speaking with Dianne and talking about those early days when she was hanging out in the Bronx with the Kangol Crew, and sneaking into parties. She would talk about the park dance, and it was two turntables and a microphone that really set that off. When you think about DJ Kool Herc, who is one of the founding fathers of hip-hop, it was two turntables and a microphone set up in a community center, set up in a park.

When you think about how far hip-hop has come on a global stage, and that it came from such humble beginnings and particularly during a time in the 1970s, in the Bronx, of the Bronx fires, and the poverty, the crime, the systemic oppression, is really amazing that this genre rose from those ashes.

Arun Venugopal: Tell us more in the context of what we would encounter if we were to encounter this common visit to the exhibition.

Souleo: Dianne is here with us, so I'll just answer this question, and then I want to give the floor to her. When you come into the exhibition, there's a lot of interactivity. That was really important for both of us because we wanted to bring in that community element. There's an amazing video piece that Dianne did that's projected on the wall and you're meant to dance with it and embody the movements and the space. We have the Two Turntables and a Microphone with a folding gate set up. It's really recreating that park environment. People go behind there, take photos, they play with the turntables, hold the mic, dig through the crates.

We also have a living room that was set up, and so people are invited to sit there and reflect on those living rooms back in the day where hip-hop was also formed in homes and look at the televisions and look at the VCR with the old Beat Street and wildstyle VHS tapes. Then we have archival material that you engage with as well. Then we have a pop-up hip-hop library, with books just documenting more of the history of it.

Arun Venugopal: As Souleo mentioned, we are now joined by Dianne Smith, the artist whose work is at the center of this landmark exhibition, commemorating 50 years of hip-hop. Hi, Dianne, thanks for joining us.

Dianne Smith: Hello. Thank you for having me, us, and talking about the exhibition. It's an honor and a pleasure to be here with you.

Arun Venugopal: The exhibition is a celebration of your work, Dianne, as well as hip-hop's birth in the Bronx, being a Bronx-born artist as well. Just broadly speaking, in what way is the culture in the field of hip-hop present in how you operate as an artist?

Dianne Smith: I think one of the things that I take from the hip-hop cannon if you will, is the idea of improvisation, which was at the heart of hip-hop. It was very organic, improvisational. There's a call-and-response aspect to it. The land and the textures of my work, hip-hop, or the sound is very layered and textured, and it infuses not just the current day situation, but if you listen to some of the lyrics, is rooted in historical context, is rooted in lived experiences, is rooted in the now, and a lot of my work centers around those things.

Arun Venugopal: I can't help but talk to you about your experience of going to LaGuardia with Slick Rick, DJ Dana Dane, and the Kangol Crew. I've got to ask you, what was Slick Rick like at the age of 16? Was he Slick back then too?

Dianne Smith: Well, he was always Slick Rick. That was his name back in the day. On the one hand, I could say we were like any other 14, 15, 16-year-old kids in New York City, but on the other hand, because we were in a school like LaGuardia, we weren't like every other 14, 15, 16-year-old kid in New York City. In 9th, 10th, 11th grade, we were making music, we were making art, we were centered on being ultra creative because that was the environment that we were nurtured in. Going to school with Dana and hanging out with Dana and Slick Rick, was really important because we started our day going into the auditorium with them banging on the seats.

We got to school early just to have a jam session. The auditorium will be packed and the Kangol Crew, which consisted of Dana, Rick, Lance, Alfred, and Wilfred, would be making music on the auditorium chairs or banging on the stage or whatever surface that they can bang on to make the beats. They would be rapping, and then Don and Tunay would be singing loops over their music. The concept of singing loops over songs was being done in music and art in LaGuardia long before it became really popular in mainstream music. They had music for MLK Day. Every holiday or thing, they had written music for.

Arun Venugopal: You're a teenager. You're having this amazing life-forming experience. You're part of something that is being birthed before your eyes, but of course, you're just living it. I'm just wondering, then or perhaps after a few years when you look back on it, did you realize what you would witness in terms of the evolution of this world-changing art form?

Dianne Smith: During the time, we did not. It wasn't something-- because it was our way of life. It was a way of expression. We were given, again, the agency to be that expressive. It wasn't like we were sitting there going, "Okay, this is going to be Martin steeped in history or whatever would have you." We were just going about the day and doing the things that we felt good doing and we were encouraged to do. It wasn't like we were in school, and they were saying, "Stop banging on the chairs or stop making--

That wasn't the environment we were in. We were in an environment that nurtured that form of creativity. We were also in an environment where everyone in the school was pretty much treated fairly and equally. There was equity in the fact that we were all there because we were talented and we were creative. We were all given the space to be exactly that.

Arun Venugopal: I want to play a cli--

Dianne Smith: [unintelligible 00:09:26] then I think that experience with us all set the tone for us to be as creative and expressive as artists as we are today.

Arun Venugopal: A good educational system that gave you free rein, I suppose, you and your friends. We have a clip here, one of our producers dug out from YouTube from the '80s. This is, I guess, Slick Rick rapping live to a beat as a member of the Kangol Crew.

[music - Slick Rick: La Di Da Di]

Arun Venugopal: [laughs] Souleo, I see you on Zoom swaying there. Is this a clip that you're familiar with yourself?

Dianne Smith: Yes, I'm familiar with that. Of course, its cadence had evolved over the years, but that is reminiscent of us being in what I just described. The cadence and the tone in which he raps today, and even Dana, is reminiscent it came right out of The Kangol Crew.

Arun Venugopal: If he came from-- he moved here in his early teens, from England, Slick Rick?

Dianne Smith: Right. He moved here from England and he was in the Northern Bronx. He lived in [unintelligible 00:11:05]

Arun Venugopal: At the time, did you think like, "Oh, who's this kid with the Slick British accent?" [laughs]

Dianne Smith: No, because again, the school was mixed with so many different-- we came from all over. I would say for many of us, it was the first time that we were in an environment where there was so much difference but the difference wasn't at the center of how we moved through the building. That was quietly embraced, if you will, because for many of us, it's the first time we had gone to school with different ethnicities, nationalities, economic situations.

It wasn't, we were taking out of our natural environments and habitats and put into-- For many of us, it was the first time we even got on the subway. We were 14. I don't think that and I don't recall us focusing on anything that made us different. What we focused on was the things that intersected and the things that connected us, and that was our creativity.

Arun Venugopal: Souleo, you're the curator of the show. It's not every day that we see an art form undertake the journey in such a short amount of time, from the nascent in a corner of the Bronx to this world-conquering idiom that is just pervaded so many societies around the world. Is there a moment when you think that hip-hop went from innocence, hey, no one's really watching, to something more self-conscious?

Souleo: Yes. We had a great conversation this past Friday with Pete Nice and [unintelligible 00:12:53] idea of Cole Quest Brothers and Sparky Dee. What came up in that was the influence of capitalism. I think the pressures of going commercial and the pressures of executives who wanted to control the narrative and stick to what was popular or easy to sell, I think really corrupted a lot of what we see in the mainstream when it comes to hip-hop. There's still pockets of that where we see the positive and the community focus but I think that capitalist structure really did a disservice to keeping the community focused that it began with.

Arun Venugopal: Which is, I guess, why you're emphasizing the making Two Turntables & a Microphone just the maker of culture, if you will, of hip-hop back to the roots, not so much the billions that flow through the coffers. I'm talking to Souleo who curated the exhibition commemorating the 50th anniversary of hip-hop, along with artist Dianne Smith, whose work is also commemorated. We'll be back after a break.

[music]

Arun Venugopal: You're listening to All Of It. I'm Arun Venugopal, sitting in for Alison Stewart. We're talking about hip-hop, namely the 50th anniversary of Hip-Hop, which is being commemorated at the Bronx Museum of the Arts with an exhibition starring the work of artist Dianne Smith. It was curated by Souleo and both of them join us now. One of the pieces, Dianne, in the exhibition is called Owed to DJ Kool Herc. Kool Herc is of course famously the DJ who is credited with starting the parties that would morph into the genre known as hip-hop. Did you ever happen to make it to one of his parties, Dianne?

Dianne Smith: Well, no. At that point, I was very young but I did make it to my-- I grew up on 178th Street & Arthur Avenue, which is right near East Tremont, Crotona Park. We would sneak off to the park and be with the older kids. The '70s was a time where a bunch of us kids could roam free and run around and do things. As long as we were traveling in a group and our parents knew we weren't very far we could-- as much as the Bronx was a [unintelligible 00:15:26] place, it was still a place where we could explore and be out and run around.

We would venture into Crotona Park to the jams. It could have been Kool Herc one point in time, I don't know because I was very young. I don't know that I would've been able to say it was one specific DJ or the next, but I do know that we were at those parties and we probably shouldn't have been because we were little kids. [laughs]

Arun Venugopal: It all paid off in the long run. [laughs]

Dianne Smith: Exactly. [laughs]

Arun Venugopal: Listeners, we want to bring you into this as well. What made you fall in love with hip-hop? Was there a specific song? If so, what was it? Bronx locals, did you ever go to DJ Kool Herc's parties at Sedgwick? Give us a call at 212-433-9692. That's 433-WNYC, or you can just text us here. A question for both of you, but I'll start with you, Souleo. As you were put putting together this exhibition, what conversations were you having as a duo about the right feel, what you were trying to get across?

Souleo: We had many conversations. One of those that was really important was that although this started with Dianne's personal archive, it was very important that it be about just universal and that it really focuses on the community, and that there's an entry point for everyone. What's amazing about Dianne's work is that she doesn't just work in one discipline, one medium. There's video, there's painting, there's sculpture.

There's an entry point for everyone to connect with the world and to find themselves within it. We have this amazing wall, this graffiti tagging wall, where people can answer a question about what do you love the most about hip-hop. That wall is pretty much full. There's almost no space to contribute to it. It really shows that the community has responded in such a positive way.

Arun Venugopal: Dianne, anything to add to that?

Dianne Smith: Yes, I can talk about it from the installing of the exhibition and it really became site-specific. You asked a question earlier about how hip-hop influenced, or the idea of it, influenced how I work. I think that installing became very improvisational because then I started responding to the space. Some of the things that we thought of or were going to do shifted while I was in the gallery. Three of the largest paintings in the show were painted on-site in response to what we were feeling and thinking about the exhibition. The site-specific installation became a response to all the conversations and the things that we were thinking about hip-hop and community.

I think along with wanting to have an entry point for everyone, I also wanted to have vocabulary within the context of the aesthetic of the work that people can speak about. That was from the archival materials to the two turntables and the microphone and have it be experiential and participatory that people could come in and take photos with the two turntables and the microphone.

Then things got really specific also, like the fence behind the two turntables and the microphone. I had bought a fence and we got it into the space. I'm like, "That's not the right fence. It needs to look like the fence that was in the park back in the day." We went out and found the fence and it was a whole thing. I would say a lot of care and thoughtfulness.

Arun Venugopal: I'm curious to hear your thoughts about the evolution of hip-hop from this very local art form to something much bigger. Souleo expressed some misgivings when he saw the commercial imperative. Do you remember when you realized that this was becoming something just exploding, and what were your feelings about that at the time?

Dianne Smith: Well, there are a couple of things. First, I want to just address the idea of it being global. As someone who's traveled and have experienced how others have experienced Black American culture in other countries, there are a couple of images from Guayaquil, Ecuador when I had gone to work with a few graffiti artists, to do murals through the State Department for Fulbright. Two young people from the community came out and they came out because they heard they were artists coming from New York to work on this graffiti and their love of hip-hop.

They were wearing their best interpretation of hip-hop attire. This wasn't about the commodification so much as it was just about what hip-hop started, how it started. It was just about the people. It was just about agency and expression of self. I think it's important to note that that still exists globally, along with all of the other spaces of commodification and the glorifying of some things that are just not good for our communities.

With that said, I think it's also important to say that it is a genre that has created more wealth in Black communities and generational wealth than a lot of other spaces. I think that those things are really, really important. Also, as much of everything else, there's historical context of everything that is seemingly positive, that filters through communities of color, gets rebranded and re-contextualized and put back out into the culture in a way that people in power think that it should be. It's not always to our benefit. I started to see that change more around the early '90s or such.

I remember my pastor at the time, Reverend Calvin Butts, was having discourse around it and folks were really thinking he was trying to censor the hip-hop artists. That's not what he was really trying to do. He was trying to hold everyone accountable for the things that were being put out into our communities in terms of some of the lyrics and things of that nature, and holding the executives accountable. It wasn't that he wanted to censor the voices, it was about accountability because in a way he prophesized some of what we see today that is happening.

Arun Venugopal: Let's take a call. This is Maria calling from Morris Plains, New Jersey. Hi, Maria.

Maria: Hi, everybody. I am such a huge fan, and I just want to say that I live in New Jersey, but I am a proud person that I was born and raised in the Bronx. I was raised in-- for the first 18 years of my life, I was at 181st between Bison Dairy. I can't tell you how these house parties really [inaudible 00:23:23] It just rest up community because we grew up in the middle of the crack epidemic. It was really bad at some points but having those house parties really made life a lot better, if that makes any sense to anybody.

Arun Venugopal: Definitely.

Dianne Smith: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. House parties, we joke some of us that remember those, remember the blue lights and the red lights [laughs] and just coming together at someone's house, at someone's apartment, and just having a good time. It was really just about the fellowshipping and the community aspect of the music. It was really about that.

Arun Venugopal: Thank you for your call. Maria. Souleo, a question for you. I understand part of this exhibition has a section where visitors are encouraged to leave their own experiences with hip hop. When someone visits the show, how exactly can they get involved and why did you think this is so important to include in the show?

Souleo: When you visit the show, once you enter, the wall is there and there's a prompt that asks you, what do you love the most about hip-hop? You can draw your response or you can write your response and just pin it to the wall. We also are requesting that people, if they have something that is archival like an archival flyer or a photo, we have a family day coming up this Saturday, so bring it in and we can make a copy and add that to the wall as well.

We thought it was important to have this again so that it's participatory, but also that we collect the thoughts and the voices of the community. We want to make sure that they're reflected and we are working on making sure that those contributions are preserved in an archive of its own, so more to come on that as well.

Arun Venugopal: I've been talking to Souleo who curated an exhibition marking the 50th anniversary of hip-hop at the Bronx Museum of Arts, as well as artist Dianne Smith. Dianne, Souleo, thanks so much for joining us today.

Dianne Smith: Thank you.

Souleo: Thank you.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.