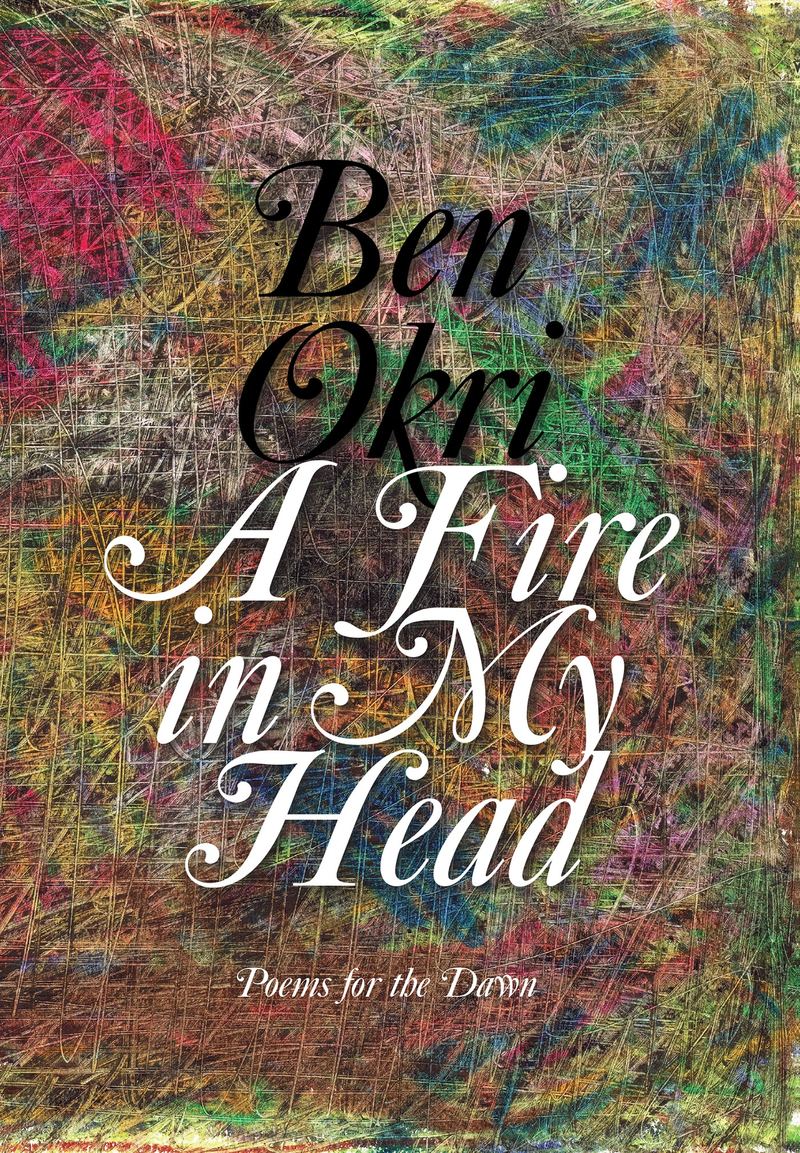

The Booker Prize Winning Ben Okri On His New Poetry Collection

( Other Press )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All of It, I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC studios in Soho. You know where I'm going to be this week and that's Outsider Art Fair, make a whole, make it wide, here I come. I Love that art fair. I'm also so glad you are here listening with us. If you're able supporting us during our winter fun drive, we cannot make shows like this and keep WNYC afloat without you, so thank you so much for considering it. Just a preview, next week's show, Margaret Atwood will join us to discuss her new collection of short stories.

We'll also talk about the new TV adaptation of Daisy Jones and the Six, with showrunner and executive producers, as well as the team who composed the music for the band, and we'll continue our conversation with Oscar nominees as we look ahead to the award ceremony. We're going to speak with the costume designer of Everything Everywhere All at Once. Really looking forward to that conversation. That is all happening in the future, but right now in the present, right now, let's get this hour started with Ben Okri.

[music]

Ben Okri is a Booker Prize-winning novelist, a poet, an essayist, a playwright, and a writer of short stories. Until recently, much of his work from the past 30 years had never been published in the US. That is changing with the help of a US-based independent publisher, Other Press, who since last year has been rolling out revised editions of his work going back to the 1980s. Those works include his 1995 novel, Astonishing the Gods, and revised versions of his 1996 novel, Dangerous Love, and his 2007 novel, The Last Gift of the Master Artists.

Most recently, just on Tuesday, came the US Publication of the poetry collection, A Fire in My Head, Poems for the Dawn. There are poems with titles like decolonization, liberty, and on race. They touch on topics like Black Lives Matter and the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire in London. There are poems dedicated to specific figures and organizations, including former President Obama and Amnesty International. Here to tell us more is Ben Okri. Ben, nice to meet you.

Ben Okri: Real pleasure to be here. How are you?

Alison Stewart: I'm well, sir. Would you start us off with the poem, Decolonization?

Ben Okri: Yes, with pleasure. It's called Decolonization and it has a subtitle from Fanon.

It never takes place unnoticed

like a blade before your eyes.

It transforms those crushed with their nothingness

into central performers under the floodlights of history's blood-like gaze.

A new rhythm, by dawn men brought, a language new minted from the Old Earth,

a humanity remade by vaporizing chains, and the brutal alembic of oppression.

It's the way new beings are forged from fire and rage,

distilled into clear dawn.

But nothing supernatural presides over this renewal.

No deities or heroes or famed individuals.

The new becomes been, the same way it became free.

Alison Stewart: That was Ben Okri reading from A Fire in My Head, Decolonization from Fanon. Is that Frantz Fanon?

Ben Okri: Frantz Fanon, absolutely.

Alison Stewart: Would you tell us--?

Ben Okri: A great--

Alison Stewart: Yes, for listeners who don't know.

Ben Okri: Well, he's a great theoretician of revolution and the effect of colonization on the psyche of the colonized. He's been one of the most influential writers of the 20th century, looking at colonization and African nations and nations that have undergone oppression throughout the world. He was a psychiatrist and he brought his psychiatric training into a study of the effect of colonization on people's minds and psyches. He had a really illuminating effect on the politics of many nations across the world.

Alison Stewart: What did you want to distil about colonization and from his work in this poem?

Ben Okri: Well, several things, but I think the most important thing is that it's an act of self-transformation, it's an act of self-liberation. To decolonize is not just casting off the colonial chain. It has to also be worked through the psyche, the psyche of an individual and the psyche of a whole people. That's why if you look at the poem, I use a lot of chemical images because a fundamental transformation has to take place and it's a very difficult transformation. Sometimes it happens to the history of a people, which can be bloody, and angry, and full of rage, and can have very calm moments. I just thought the poem was best expressed that difficult transition.

Alison Stewart: In this book of poetry, after the table of contents, after the listing of the poems, there's tiny small instructions that say, "Read slowly," at the bottom of one page, [chuckles] that's all it says on the page. Why is that important for readers to keep in mind, 'Read slowly'?

Ben Okri: I think we've been in a too fast reading phase for a long time. I feel that we read too quickly, we listen too quickly, we understand too quickly, we analyze too quickly, we criticize too quickly. The thing is that when we slow down our reading, we deepen our comprehension/. When we slow down our listening, we deepen our hearing. I've come to right now in this stage of my writing life, this last 15 years, I have come to write in a very compressed, elliptical way. You get the music of what I'm writing, of my language best when you slow down because all of the music, and all of the magic, and all the power, is actually inside, and if you read fast, you miss the nuances.

Alison Stewart: That's also an interesting idea for someone to take time for themselves to slow down.

Ben Okri: Yes, absolutely. We need to slow down in our living, we need to just walk a little slowly sometimes, enjoy the silences of life, just watch a cloud scudding across the sky, listen to the music of people's voices.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Ben Okri. We're discussing his poetry collection, A Fire in My Head, Poems for the Dawn. We'll talk more about the poems in a minute. I just want to get to more from the beginning of the book before we dive in. There's a lot to experience. There is the Yeats quote, "I went out to the hazel wood because a fire was in my head, from The Song of Wandering Aengus. What was it about this poem that you took the title from your book from it or that you wanted to include these two lines?

Ben Okri: Well, first of all, which of us poets doesn't love Yeats? This is early Yeats, this is mythic Yeats, this is Yeats exploring the relationship between the land and mythology. To be honest with you, I was really rather surprised that nobody had-- because Yeats is very much mind for titles, is one of the most used poets for titles in the world. I was very surprised that A Fire in My Head, this wonderful phrase from Wandering Aengus hadn't been used. It's a magical little poem.

A Fire in My Head spoke to me really deeply because I've been [unintelligible 00:08:31] quite a few fires in my head for a while, political fires, mythic fires, fires about love, spiritual fires. The whole idea of a fire in your head is it turns your head into a cauldron. It goes back to alchemy all over again. It's as if you've got this heat in your head that you really need to share. It was just a perfect title and I was very lucky that no one else had nabbed it before me.

Alison Stewart: The collection is divided into five sections, unknown hour, convergence, midday, dusk, invocation hour. What made sense in that arc? Why did that arc make sense?

Ben Okri: Well, first of all, it is designed to track the medieval Book of hours. Anyone who knows the paintings that they combine with books in the medieval times, you can see these in many of the great galleries, they divided the spiritual life into hours. Not only that traces the hours of the day, but it's also the hours of a life, the hours of the development of the spirit, and I also take it to be the hours of spiritual growth. In this book, it's divided that way because they're political poems, mostly. They start with the unknown hour from which many of our difficulties come, and into which they go. It develops into convergence because that's the place where the problems and difficulties become visible. They converge and we see them. Midday is the hour of heat, and the forge and tempers and anger. Dusk is, it's darkening. Invocation hour is when we find a new kind of energy to deal with these problems. The whole book, in a way, is a meditation on the hours of the political program, of the individual and the poet. Looking at what's going on in our world. I needed a structure for this volume and this medieval book of hours was just perfect for me.

Alison Stewart: Ben, would you read another poem for us?

Ben Okri: Ah, do you have a choice?

Alison Stewart: How about How Many Ways?

Ben Okri: Okay. How Many Ways is a wonderful one to choose, because it's a new poem I wrote especially for the American Edition. "How many ways can a world be destroyed?," she asked skeptically. He drew a breath in the darkness of the day after the Mayan end of the world, and in a blue voice said, "The world can end in many ways. It can end with a ship coming to a shore." "Oh, I can see that," she said. "Only," he replied, "because you believe history is truer than a symbol." "And what else," she asked? "The world can end with the breaking of an egg." "I fear," she said, "you are getting esoteric."

"Not at all," came he quietly. "A symbol is more accurate than history." For the first time she was silent, maybe the mystery of symbol was the cause. Maybe she sensed more. "The world can end," he said, "with a kiss." Then she gasped. "It can end with a touch, with a sound of a voice, a light in a distance. An odd shaped moon can end with an idea. The birth of a child or a road taken too long." She was no longer listening. Maybe her listening had taken her to a distant river, a childhood shoreline, where an arriving ship brought her dark afternoons and snow.

Alison Stewart: That was Ben Okri reading from his book of poems. This is called How Many Ways, a new poem for the American edition. When did you write this poem? What inspired this for this particular collection?

Ben Okri: [laughs]. Oh, this was written about seven, eight years ago. I tend to write poems and leave them, forget them. Come back to them when they call to me. It was really based on a conversation I was having with someone I just met. We're talking about the ancient world. We're talking about Africa, the Caribbean. We're talking about how worlds ends. A ship on a distance, I was thinking about the ships that came to many countries in Latin America. I was thinking about ships that came to America itself, the ships that came to-- I was just thinking about the ways in which worlds end. What are worlds? A world can be the dream of a people in a little enclave. A world can be our big world and the climate catastrophe.

For me, it was a very open meditation. All of these things just there in a simple conversation. I think it was just right for the American collection at this particular time because [laughs] we're not asking that question, "How many ways can a world end?" We're having to deal with that every day. Anyone who's got the slightest feeling about the climate catastrophe hanging over us is asking that question, "How many ways can our world end?"

Alison Stewart: There's a line in the poem that just leaps out, "A symbol is more accurate than history." Is that because [laughs] the history we read depends upon the point of view of who writes it?

Ben Okri: Absolutely. History is one of the most contested things. What is history? Who declared it to be history? Who wrote it? From whose point of view? How objective is it? How inclusive is it in all the truths? How many true defeats are contained in the big-heartedness of its narration? History is contentious and will always be contentious because there's so many voices that are not heard that emerge much later on and say, "Well, actually, I was there. My voice is not recorded."

A symbol, a symbol is truer. A symbol sometimes emerges from the depth of consciousness, from the distillation of our lives. It's just there. It just holds the truth of a moment or the truth of an understanding. Unwavering, whether the symbol is a circle or it's a lamp held up in the dark or whether it's a fist, or whether it's a kiss sent across an empty space to someone who is departing.

Alison Stewart: The collection includes a poem, The Viewers. It's very well known. Grenfell Tower, June 2017th, about the fire that started in a mostly low-income London high-rise killed more than 70 people. Your reading of the poem has been viewed more than 6 million times on Facebook. When did you know this poem was resonating with people?

Ben Okri: I don't know. It took a while before I became aware of that. You see, the thing is the Grenfell Tower disaster happen not very far from where I am, around three, four o'clock at night. You can already smell the ashes as well as the bodies. I know the smell of burnt bodies because I grew up during the Civil War. I wrote it through all of that and read it out on TV. Then, not long afterwards it was just reproduced everywhere. It was reproduced on walls. It was reproduced in newspapers. People were responding in America and New Zealand, Australia, Africa.

It was very, very moving. That this fire in Central, in London touched so many lives. I've been wondering over the years why that is. I think it's because of the [unintelligible 00:17:16] ancestral fear of being burnt alive that most people have, as well as a profound sympathy for those people in that tower who didn't have anything to help them escape. There's nothing there. There's no stairwells that they could escape down. There's no fire extinguishers. It was a great indictment of a system that doesn't value the lives of the poor as it should value all lives.

Alison Stewart: Ben, how is your process different when you're writing about something that's very real and very specific, versus that work that the muse sends to you?

Ben Okri: That's a great question. That's a really wonderful question. I think with something like the Grenfell, I go into a state that is close to breathing. It's very, very strange. It's like descending into my own underworld. I sink myself into a state. It's not an emotional state. It's not really anger or anything like that. I just sink myself into a condition of absolute feeling as it enters into language. Those poem are never driven by my head, never driven by my intelligence, never driven by my knowledge of the great poetry of the world. They're just driven by this pure feeling.

They're very difficult to write sometimes, but this one, it took me five hours. I just was writing with internal tears just for five hours and then came out of that state and then spent some time writing it. The most important process is submitting oneself to this state, that there's no other words for it, but akin to a huge grieving that's taking place inside one. I think like many people, I have a lot of unfinished grieving inside me, which is, strangely enough, a terrible thing to say. It's a great well, a great source for poetry, even love poetry.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Ben Okri. The name of the poetry collection is A Fire in My Head. Ben, would you take us out on another poem? Your poem of your choosing?

Ben Okri: Oh. Okay. A poem of my choosing. I want to read you a love poem. I want to read you poems about poetry, but I I'm going to read one that was suggested earlier. I'm going to read Africa is a Reality Not seen-

Alison Stewart: Terrific.

Ben Okri: -because it gives me an opportunity to share certain feelings I have.

Africa is a Reality Not Seen

Africa is a reality not seen, a dream not understood

Its wars are the scab of a wound

Its famine, the cracking of seeds

It's dictatorships, a child torturing beetles in a field

Its soul is older than Atlantis

And like all things old, it's being reborn and doesn't know it

Countless cycles of civilization and destruction are lost in its memory, but not in its myths

Africa is a living enigma

An old woman taken for a child

A wise man taken for a fool

A beggar who is also a great king.

Alison Stewart: You've just heard Ben Okri reading some of his poetry from A Fire in My Head, Poems for the Dawn. Ben, thank you so much for sharing your poetry with us.

Ben Okri: It's been wonderful having a conversation with you. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.