'The Spook Who Sat by the Door' Restored at BAM

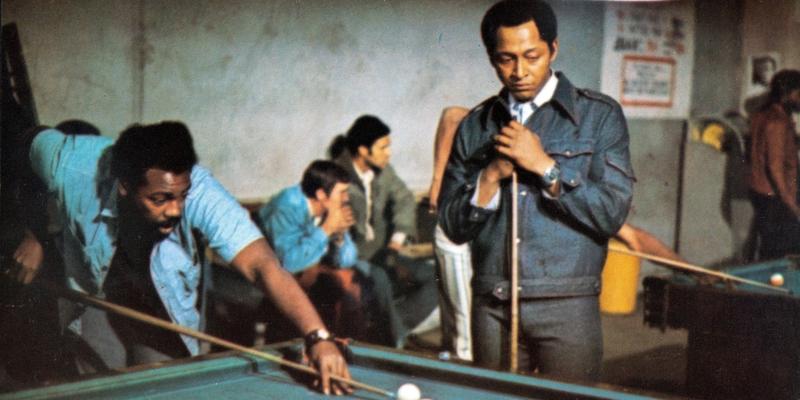

( Courtesy of BAM. )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Starting this Friday, you have the chance to see a radical and rare film in theaters more than 50 years after its original run was cut short. The Spook Who Sat by the Door was a revolutionary movie released in 1973. Based on the novel is the fictional story of Dan Freeman, the first Black recruit to the CIA, and on the surface, he is a token buried in the copy room, but Freeman is in it for the long haul. He takes what he learned in training back to Chicago and leads a group of Black militants. Written by author Sam Greenlee and directed by filmmaker Ivan Dixon, the film is both a satire and a serious exploration of Black identity, different perspectives on anti-racism, and American white supremacy. The movie initially was marketed as a "Black exploitation film," but its political overtones made it controversial, and the film was removed from theaters. Greenlee himself claimed that the FBI got involved, urging theaters to stop screening it. After receiving a restored DVD release in 2004, The Spook Who Sat by the Door was added to the Library of Congress National Film Registry in 2012. Now, a 4k restoration of the film makes its world premiere this Friday at BAM Rose Cinema. It'll screen for two weeks there, and then at the Maysles Cinema in Harlem. Joining me now to talk about the restoration is, I hope I get this right, Nomathande Dixon, daughter of Ivan Dixon, the director. Hi, Nomathande.

Doris Nomathande Dixon: Hi. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: Also joining me is Natiki Hope Pressley, daughter of Sam Greenlee, author of the novel, and writer and producer of the film. Nice to meet you.

Natiki Hope Pressley: Hello. Thank you for having me.

Alison Stewart: Nomathande, Friday will be the world premiere of this new version of the film. When did the project to restore the movie begin?

Doris Nomathande Dixon: Well, the project to restore actually began in late 2020. My family, my mother, my brother and I had met a gentleman who worked on the restoration of nothing but a man. Through my contacts with him, he informed me that the Library of Congress really had a stake in the game in terms of working to restore pieces, make sure they're preserved and all of that. He introduced me to some contacts at the Library of Congress, and we began speaking, and the next year, we submitted for grants.

Alison Stewart: Tell me about the technical challenges that were involved in restoring the film.

Doris Nomathande Dixon: Well, fortunately, my father had kept the masters in a vault-

Alison Stewart: Great.

Doris Nomathande Dixon: -from the beginning.

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Doris Nomathande Dixon: He had kept them very well in a vault in Hollywood. The assets were really in very good condition, both audio as well as the film. Very limited damage at all to them. It really was not as difficult to restore at this time. There was one other digital remaster in the early 2000s, but again, the assets were in very good condition, and so it went very well.

Alison Stewart: Natiki, the novel, was published by a British house, and your father said it was rejected by almost 40 American publishers before it was picked up. When it was finally published, what was the reception like in the States?

Natiki Hope Pressley: Well, so you're right, it was a long journey. He got it published in the UK, and when it finally got to the US, honestly, people were buzzing about it right away. The book was very controversial. It was communicating things that people really weren't saying out in public as much. It was a great opportunity for people to read a story about uprising and revolution. It was a kind of an underground thing, but it got around very quickly. I know people who still have their original copies.

Alison Stewart: The story follows the fictional character of Dan Freeman, CIA's first Black recruit. Your father, Natiki, had some experience in the government himself. He was in the US Foreign Service in the '50s and the '60s, is that right?

Natiki Hope Pressley: That is correct, yes.

Alison Stewart: What did he tell you about that time in the Foreign Service, especially for a Black man?

Natiki Hope Pressley: Well, he didn't really talk much about it. His original reason for going into the service was really to pay for college. He wanted to be able to pay for his college education. He went, like a lot of people did, to get a GI Bill. When he got to the military, he discovered that there was a lot of things going on that he did not agree with or he was very uncomfortable with. For some time when he was working in the Foreign Services, he was a propagandist, which a lot of people were like, well, what is that? He was really responsible for sharing the story of what was happening at the time, where he was located in Baghdad, in Afghanistan, and so many other places to communicate that information back to the base in the US. I think in the process of all of that, he got mixed up in a lot of things, got to meet a lot of people, and learned a whole lot about foreign relations.

Alison Stewart: How do you think his experience informed the way he portrays Freeman's experience in the CIA?

Natiki Hope Pressley: Honestly, to some degree, it's semi-autobiographical, in that a lot of that storyline definitely comes from his own experiences in the service, and all the things that he was exposed to, the things that he learned. It really is a lot of people ask me that question, like, is it really him?

It's pretty much a lot of-- There's some portion of the story, especially there's a scene in the movie where he's talking to Willie, and he's talking about his grandmother who couldn't read, and he would go back and run home because he wanted to help his grandmother read. That's actually a real story that's really true for him. He put a lot of himself into Dan Freeman.

Alison Stewart: Nomathande, your father took on this film. He was a well-known actor. He'd appeared in more than 100 episodes of Hogan's Heroes up until the '70s. He directed TV episodes, but this was only, I believe, his second feature film. What did the film mean for his career?

Doris Nomathande Dixon: Well, the film meant many different things for his career. His career was long. It began on Broadway in 1957, and a lot of acting credits before the directorial debuts in the late '60s. The only other feature film he did do was Trouble Man, which was right before The Spook Who Sat by the Door. He really did that film to basically prove that he could handle a feature-length film.

The Spook Who Sat by the Door was obviously a book that he had read and was completely blown away by. Read the book, slammed it down on the table and said, I must make this film. It was a great risk to do this film. The content, obviously, the independent filmmaking, the money to get the film done, all of that was on the line. It was a risk that he was really willing to take because it was message and themes that resonated totally with him, and it was something that he wanted to say through film.

Alison Stewart: We are talking about the restoration of The Spook Who Sat by the Door. You can see it at BAM and the Maysles Cinema in Harlem starting this Friday. My guests are Nomathande Dixon, daughter of the director and actor Ivan Dixon, and Natiki Presley, daughter of the author Sam Greenlee. Your fathers, they didn't have permits to shoot the film where it takes place in Chicago, and according to NPR's Code Switch, the themes of racial strife. For Sam Greenlee, plan to film did not please the then Mayor Richard Daley.

Let's start with Nomathande. What obstacles did your father face in just getting the movie made?

Doris Nomathande Dixon: Well, certainly the funding was the biggest obstacle in getting it off the ground. They actually went to individuals within the community to get investment in the film. They would take multiple investors and put 5,000 at a time together and to create a core budget for this. It was later on that United Artists came in and pulled in some completion funds for it.

The struggle in terms of getting funding for the film was, of course, number one, in Chicago, you're correct. There was pushback in having any filming take place in Chicago. Mayor Richard Hatcher was instrumental in most of the filming taking place in Gary, Indiana, which looked very much like Chicago. That was a wonderful experience. Mayor Hatcher and all of the support team around him, they were very supportive of the filmmaking there.

Really getting the film off the ground and into completion was frustration, and then, obviously, the banning of the film and the pulling of the film, and then wanting to redistribute the film. It was difficult over the years in terms of continuing to try to push the film out there.

Alison Stewart: Natiki, the movie was released in theaters around the country but only briefly. It was reportedly withdrawn from circulation after only a few weeks. United Artists pulled it for "bad box office," but Sam Greenlee described it as pressure from within the FBI. First of all, what was the response to the film when it first came out?

Natiki Hope Pressley: I've heard a lot of stories. I was still a baby when this was happening. The stories that I've heard from people who actually went to the theaters, I had one woman, Teresa Stovall, who told me that she had seen it and when she was in college, and she said she went back to go tell her roommate, oh, my gosh, you got to see this film, and by the time she got back to go see it with her roommate, it had already been pulled.

Alison Stewart: Oh, wow.

Natiki Hope Pressley: For so many people, I think part of the challenge was, I mean, I think it's good and bad. I think it was terrible that they pulled it because it was a great film that really a lot of people would love to have seen at the time. It also made people curious about why it was pulled. I know that generated a lot of publicity. A lot of people were asking. There's a lot of buzz about the film after that. It not being available for a time was really, I think, what helped to build the momentum. Then when it was later released on DVD and so forth, people still love that movie. Even the people who just go ahead and have pirated off of YouTube, they all say that they're doing anything they can to try to see this movie. Thankfully, we watched and sat with an audience, a live audience recently, and felt that energy, that same excitement, and we're really, really grateful for that.

Alison Stewart: Nomathande, so what did happen to the film in the 50 years since it was released? Did it have any other theatrical release?

Doris Nomathande Dixon: Yes, so soon after it was pulled and negotiations went on with United Artists, there was an attempt to redistribute. There were some screenings, of course, that took place during that time. Over the years, the film has been taught consistently within film schools across the country. There has always been inquiries and requests to screen the film in different locations. Along with the underground, interest in the film and being seen in that way, there were also always one off screenings, et cetera, that occurred, whether here or internationally. It was in 2004, though, that a significant effort was made to redistribute on DVD.

Alison Stewart: As people go see the film, it was great to re-see it. What questions do you want them to ask each other? What conversations do you want to have people talk about? Noma?

Doris Nomathande Dixon: I think for sure that one of the things that my father really believed in film and the medium is being a way to communicate to audiences. He was an activist himself. I believe that the work really resonated with him because it aligned with so many of his beliefs and his thoughts on race. He wanted the film to provoke thought. Whatever conclusion you may come to, he really wanted the audiences to walk away thinking, and really doing some self-evaluation, etcetera. The film really does that. We were talking about you can see it many different times, and you'll come away with something different each time. It's very layered.

I would like for folks to come away really thinking about things as they are today. It's amazing that some of the same issues still resonate. We're dealing with these issues today. It's a thought-provoking piece, just like the book was thought-provoking.

Alison Stewart: The Spook Who Sat by the Door, you can see it at BAM and the Maysles Cinema in Harlem starting this Friday. My guests have been Nomathande Dixon and Natiki Pressley. Thank you so much for sharing this film with us.

Natiki Hope Pressley: Thank you for having us.

Doris Nomathande Dixon: Thank you.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.