'The Pitt' Season 1 Finale Airs Tonight

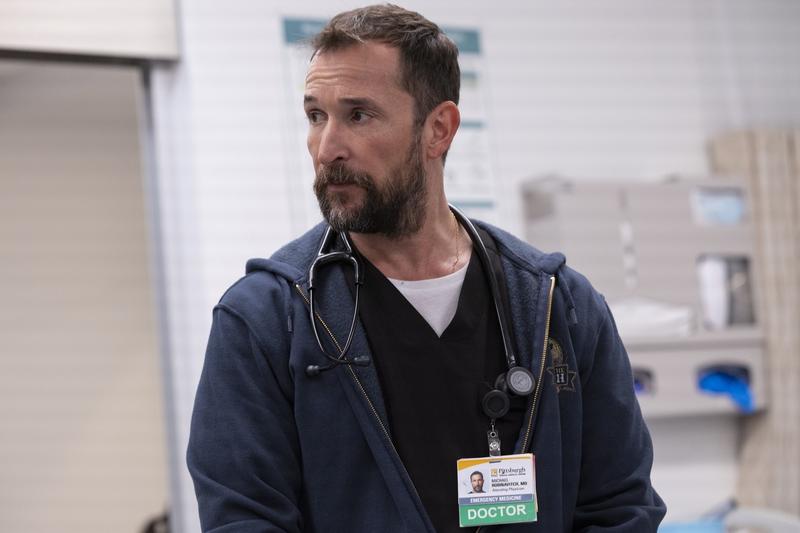

( Credit: Warrick Page/Max )

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It, on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Tonight marks the finale of one of the critically acclaimed new shows of 2025 so far. I'm talking about The Pitt. The unique medical drama follows a group of emergency room doctors and nurses over the course of one 15 hour shift. We begin with 7:00 AM, and now, 14 hours and 14 weeks later, we're approaching the end. The series stars Noah Wyle as Dr. Robinavitch, known to his patients and colleagues as Dr. Robby.

Dr. Robby is in charge of this teaching hospital, which means instructing medical students and residents. On top of all this, Dr. Robby is grieving. He's working on the anniversary of the death of his mentor. That doctor died during the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the course of the season, Dr. Robby has faced challenge after challenge. Most recently, he and the team have had to care for people in the wake of a mass shooting at a music festival, a festival someone close to Robby attended.

Noah Wyle joined us back in February when the show was taking off. Since we spoke, The Pitt has exploded in popularity, quickly becoming one of the year's most talked about and beloved series. Tonight at 9:00 PM, Max will air the finale of season one, but fans can rejoice. The show has been picked up for season two and production is already underway. I began my conversation with actor, writer and executive producer Noah Wyle by asking him what opportunities and challenges the show's unique format presented him as an actor.

Noah Wyle: It has built in advantages and disadvantages. The advantages are we shoot in consecutive order, which you rarely do in film production. We shoot for about eight or nine pages of our narrative and then we kind of hermetically seal the set, then we come in the next morning, and we move the narrative along another eight or nine pages, which makes the set live all the time.

If I put a coffee cup down, it stays there until I pick it up again, but you get to build your performance in aggregate. The downside is that that aggregate, over nine months, gets rather intense, until you're finally, in the latter rounds, having to come in every day, already having absorbed everything else that's taken place, and start from that high place of anxiety or tension. It was a challenge towards the end there.

Alison Stewart: Yes. It's interesting because it's clear that Dr. Robby has an interesting backstory, but we're finding out a little bit at a time. How are you able to bring that to the role, his backstory, without just a ton of exposition?

Noah Wyle: It's the advantage of the device of doing everything in real time over the 15 hours, is you can really peel the onion very slowly, and a little goes a long way. When you give only a few pieces of character backstory information per character per hour, those become really satisfying nuggets. They stand out in the relief of not getting a lot of exposition, watching them in the professional capacity.

The intention in the writing is to show personality and evolution through the professionalism, so that you're getting a sense of the person, how they react to pressure, how they react to praise, organically, as opposed to having it be a narrative device.

Alison Stewart: You're an executive producer on the show, you've written a few episodes, you act in it, obviously. What were some creative decisions that you made, and you knew that you wanted to make, to make this feel like a real ER?

Noah Wyle: Well, we-- I say we, I'm speaking for--

Alison Stewart: The collective we.

Noah Wyle: Well, in this particular case, I'm speaking for John Wells and Scott Gemmill, who I had the great fortune of working with for many, many years on ER, and who I'm working with now, as partners on this. We wanted to not repeat ourselves. We wanted to go a little farther than we were able to go before in our storytelling, in this arena, but we were also cognizant that we had set a pretty high bar for ourselves.

Part of that bar was in delivering to audiences a new cinematic language on immediacy and pace that ER gave television. How do you recreate that without redoing it? How do you come up with a new way of giving that same sense of intensity and voyeurism, active participation? This real time structure works really well for that.

Alison Stewart: The series takes place in Pittsburgh. What were some of the details about Pittsburgh that you wanted to get into the series without ever actually leaving the space? This is the ER.

Noah Wyle: As many as we could. As many as we could. I wrote an episode that referenced everything from Primanti sandwiches to Mr. Rogers to a couple of boxers that are known for having trained in Pittsburgh. That's part of the research. That's part of the fun of adding texture to the narrative. It doesn't matter if it's Pittsburgh, New York, or Chicago, every city has a Primanti sandwich.

They just call it something different. Sometimes, the more specific you are with the reference, the more relatable it is in the Universal. It's the ODD paradox, that the more you really drill down on somebody's peculiar nature, the more he becomes relatable to everybody.

Alison Stewart: I wanted to ask about the show and its reaction to COVID-19. It strikes me as one of the first shows that really deals with the aftermath of COVID-19. Dr. Robby is working on the anniversary of his mentor. We see that through flashbacks. First of all, did you talk to frontline workers about the aftermath of COVID-19?

Noah Wyle: This was sort of born during Pandemic in real time, with me getting a lot of mail from first responders and people on the front lines, who were grateful to have been inspired by my character on ER to go into this discipline. They were also very confessional in their tone about what it was like to go into work every day and how their morale was flagging and their ranks were thinning, and it sounded like a call for help.

A lot of the intentionality behind the show was to put the spotlight back on this community, to remind everybody what heroes they are, picking up our broken pieces every day, to underline the fragility of the system, and how it is as fragile as the quality of care we give our practitioners. For the first time in 30 years since ER went on the air, they didn't match all the applicants in ER positions this year. After Covid, those ranks have been thinning. We wanted to inspire the next generation to join up, because we're going to need them, most likely.

Alison Stewart: What questions did you have when you were first approached about this project? You had done ER, as you said, people still write to you, which is interesting. That's another whole conversation. What did you have? What concerns did you have about another medical drama?

Noah Wyle: Trashing our own legacy, falling short of the bar that we'd already set for ourselves, looking like we were trying to milk some more money out of an old cash cow, taking a vanity lap around the track. There were a lot of things that we were extremely conscious, that, optically, we wanted to avoid. We were all at a stage and age in our lives and careers where we felt like there was one more rung we hadn't reached yet, one more thing we hadn't done yet.

We all remembered an experience that we shared that felt idyllic, validating, inclusive, fun, and impactful. Then we all went our different ways and had various forms of that, but never quite that combination again. Coming back together and experiencing it again validates that it happened the first time and proves the thesis that you can run a show a certain way, the way John Wells runs his shows, and have a very successful show that's really a pleasure to be part of.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Noah Wyle. We're talking about the Max series The Pitt. Episodes of this medical drama air on Thursday nights. For you as an actor, what's the difference between playing a young, upstarting doctor, and now a more seasoned doctor like Dr. Robby?

Noah Wyle: 30 years, 20 pounds, eyeglasses.

Alison Stewart: I feel you, my friend.

Noah Wyle: It's been wonderful. I've been trying to find the right analogy for it. It comes close to having played an instrument for a really long time in your youth and then not having played it for a long time, then you pick it up again, and yes, there is some rust, but there's a whole new quality to the tone that comes with age and maturity, that feels earned and synchronistic.

Alison Stewart: Your voice is different.

Noah Wyle: It's different. It's aged. At the moment, it's full of LA wood smoke, as our city just got finally put out. It's also years of yelling, screaming, dying, crying, and falling. I've been doing this a while.

Alison Stewart: I believe the Internet. You and your co-stars went to a boot camp with doctors.

Noah Wyle: Yes, we arranged a two week boot camp for all the cast, myself included, to come in and basically go through a condensed version of medical school. That was a syllabus designed by our technical advisor, Dr. Joe Sachs, who's also a producer and on our writing staff, and a general Swiss army knife for us. We segregated ourselves into the hierarchy of our roles within the hospital.

Alison Stewart: Oh, that's interesting.

Noah Wyle: Med students got clumped together and they learned med student stuff, and R1s learned R1 stuff, R2s. I kind of played the band. I was a conductor. I went around, dabbled in everybody's station, and mostly just tried to remember how to do everything.

Alison Stewart: The scenes in the operating room, when people come in, they feel choreographed. First of all, are they?

Noah Wyle: Very much so. Very well rehearsed and very well choreographed. Yes.

Alison Stewart: Tell us a little bit about that process, the rehearsal process.

Noah Wyle: Telemedicine is its own discipline. It not only has to look medically accurate, but it has to be visually interesting as well. The choreography involves making sure you're doing the procedures correctly and in real time, but also making sure you place items around the room, so going for them and handing them to each other has a kinetic quality to it. Then on top of that, you want to make it look effortless and you want to make it look a little sloppy if you can, so that it feels real.

It really requires a dynamic, almost theater trained performer to really pull it off well. When we went out looking for this cast, that was one of the prerequisites, was you have to be able to walk, talk, chew gum, and do a thoracotomy backwards down a hallway, for seven or eight pages, uninterrupted. It requires a real discipline and a lack of ego. We were really fortunate to get all these performers to answer that call, and it shows on screen.

Alison Stewart: You used to be on network tv. You can show a lot more now, when you know too much is too much?

Noah Wyle: Well, yes, you could get heady with power, "Yes, yes, I can say anything. I can show anything," but once you get that freedom, which is really liberating, by the way, then it becomes about taste, discretion, and appropriateness. Yes, we have all of our patients sign non sexual nudity waivers when they come in, because trauma patients get their clothes cut off.

We do photograph nudity, not gratuitously, but if it's part of the procedure, we don't avoid it, similarly with language or some of the incredibly photorealistic wounds that we're able to depict. It all underscores the sense of reality that we're trying to achieve, but that's no different than not employing music or a theme under any of these scenes. We want this to be as immersive experience as possible.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk about your character. Do you think Dr. Robby likes the ER? He likes working there?

Noah Wyle: I think he should have left a while ago. I think he feels pressed into service out of habit, need, and lack of self awareness. He senses a little bit of a metaphor for a lot of healthcare practitioners who went back into practice, or continued to stay in practices, out of that need and sense of responsibility, without really ever having the opportunity to unpack emotionally what they've been through, and to try to find some balance in their own lives. Robby is a perfect example of that.

Alison Stewart: Let's listen to a clip of Dr. Robby. He's interacting with one of his doctors, who's sometimes a little slow to work through cases. This is episode seven. Let's listen.

Speaker: Look, the FDA website has a list of imported products that contain mercury. She's been using this one. I've ordered a heavy metal panel looking for mercury, lead or arsenic.

Dr. Robby: Why didn't you consult me?

Speaker: I consulted Dr. Collins.

Dr. Robby: Dr. Collins is not supervising this case.

Speaker: I know, I just didn't know if--

Dr. Robby: If what?

Speaker: I thought you were having a bad day.

Dr. Robby: Did Dr. Collins say that?

Speaker: No, she was just trying to help.

Dr. Robby: Don't ever do that again.

Alison Stewart: What are Dr. Robby's-- What are his strengths as a boss? What are his weaknesses?

Noah Wyle: He's a great teacher. He's a perfect example of "do as I say, not as I do." He learned medicine from a really brilliant man and absorbed everything that that man had to teach him. That guy was a surrogate father figure to him. During COVID, that man got sick, Robby had to put him on a life support system, and then eventually take him off that life support system, to give it to another patient who had a better chance of survival. Then everybody had a bad outcome.

It's just one of those many micro traumas, major traumas that have built up in aggregate that he's been able to compartmentalize for the most part, and function, but this is a day where he just gets triggered continually, and suddenly, those compartments are no longer able to be hermetically sealed.

Alison Stewart: I'm thinking about the father who has to be intubated, and Dr. Robby is really against it, almost forcefully against it. When you think about, first of all, why is he so forcefully against it? It almost seemed out of line with what a doctor should do.

Noah Wyle: Well, if your first oath is to do no harm and you know you can't do any good, then the kindest thing that you could advocate for is to not continue to cause suffering or discomfort. At a certain point, as we leave this world, it becomes no longer something that we can avoid. Then it becomes a question of how we want to attend these last moments. Do we want to frantically thrash this body and put it through all sorts of torturous procedures to try and eke out a little bit more existence?

Is there a more holistic, humane sense of closure that we could come to? I think that most practitioners have dealt with this moment before, where the desire to keep someone alive, a family member's desire to keep someone alive, overrides their rationality to really do what's best for the patient. I think Robby's advocacy there is just-- He's seen this too many times, he just knows that this is not going to work any other way, and he just doesn't want to hurt this guy.

Alison Stewart: A lot of the patients, they don't necessarily accept that dying is a part of life.

Noah Wyle: I think it's something we rarely ever really depict on television or in media accurately, for all the deaths that we absorb every day when we watch television, and for the frivolous way with which we dispense of life in most of our popular entertainment. Focusing on just one person leaving this world has had tremendous impact, from what I've been hearing. That episode has really touched a lot of people. I think it speaks to the vacuum of that conversation and the fact that a lot of us have aging parents.

That boomer generation is huge, they're all getting older and they're going to get sick. These are conversations that are going to attend every household soon, about what are we going to do with mom, what are we going to do about dad, what would they want? Yhat kind of thing.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Noah Wyle. The name of the show is The Pitt. Episodes appear in this medical drama every Thursday nights. I'm curious what people have talked to you about the show, people in the medical profession. Let's start there.

Noah Wyle: I just was in Pittsburgh yesterday, and I toured three different hospitals. One that we shot in, Allegheny General, I went to children's, and it was rather intense experience to see how this is resonating with the people that work in hospitals, except for respiratory therapists, who are underrepresented. I understand that, and we will rectify that in a second season. Also, physical therapists. I understand that you also feel like you're not represented, but everybody else feels pretty good.

Alison Stewart: That tells me you had a physical therapist up in your grill a little bit.

Noah Wyle: I saw a couple people across the room, with their arms crossed, looking a little dour, but for the most part, not only did they feel that we were depicting something that's accurate, but they felt that we were depicting something that their loved ones could watch and have a sense of understanding about what they do and aren't ever able to articulate. We're showing what they can't say.

I'm hearing a lot of people say, my kids were like, "But that's not what you do," I said, "Yes, that is what I do," "But there aren't that many people waiting." "Oh, yes, there are more sometimes," "But you don't really stick tubes out." "Yes, I did that twice today."

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Noah Wyle: It's, I think, overdue.

Alison Stewart: This is a really interesting comment that somebody sent in, "After every new episode of The Pitt, I follow Max's suggestion and binge a few episodes of ER. I love both. So impactful, but one real change in medicine is obvious. Technology. Charts versus computers." That's interesting. Did you find that?

Noah Wyle: Somebody told me recently that they were showing an ER clip to their med class and they weren't familiar with radiology film, that X rays aren't part of the medical education anymore because everything's digital. Then, it suddenly dawned on me that we don't have any light boxes on our set, that we never put up films, that that's something we did with such regularity, you never see it anymore. There's been so many incredible advances, especially in emergency medicine.

The diagnostic tools that they have at their disposal, just intubations alone. If you go back-- which I think everybody knows how to do, if you ever watch the ER, it's when you stick a tube down someone's throat. We used to use this tool that's curved, we'd stick it down your mouth, and we'd blindly have to figure out where your vocal cords were. Now it's all fiber optic. They have these things called glidescopes, you're watching on a screen, and it's relatively simple to do with all this new tech.

Alison Stewart: Can I ask a practical question?

Noah Wyle: Please.

Alison Stewart: The set, is it an actual set? Are you filming in a hospital?

Noah Wyle: It is a beautiful set that occupies two sound stages on the Warner Brothers lot in Burbank, but it is a pretty accurate photo representation of Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh. We use a lot of the same historic touches, bricks, and color tones, but yes, it's an incredible set designed by a woman named Nina Ruscio, wonderful production designer, who had to build that set before we really began writing the scripts.

Which is really atypical, because we couldn't write a show that takes place in real time without understanding the physical dimensions of the space. We needed to know how long it took to get from one room to another, so we needed to build the set to be able to do it. It was a little cart before the horse. We asked her to build us an arena and then we built the play.

Alison Stewart: What do you like about working on the show? When you sat down, I said, "It's really nice to meet you." It's great to talk to somebody who's got something interesting to talk about.

Noah Wyle: Yes, this show is a bit of an answered prayer. I had a mantra the last few years, of, "Please put me in the company of first class artists, with good hearts and minds, doing meaningful work." It's not that I haven't enjoyed the things I've been involved in, and it's not that I haven't enjoyed the people I've been doing it with, but I have been thirsty for something that I felt would have impact, personally and globally.

I wanted to scratch an itch within myself and I wanted to see whether or not, if I did it right, it would resonate. This has been an extremely gratifying experience because it came from a place-- basically of walking around the same studio that I'm shooting in for 192 days, with a picket sign during two labor strikes, as I fantasized about what kind of work I wanted to do and who I wanted to do it with. This feels very much like an answered prayer.

Alison Stewart: What was that mantra again?

Noah Wyle: Please put me in the company of first class artists, with good hearts and minds, doing meaningful work.

Alison Stewart: [unintelligible 00:22:26] I remember that. Noah Wyle stars in The Pitt. It is available on Thursday nights on Max. It was really nice to meet you.

Noah Wyle: Likewise. Thank you so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: That is my conversation with Noah Wyle, the actor, writer and executive producer of the new Max medical drama, The Pitt. The season finale airs tonight at 9:00 PM.