The Gritty Films of 60s and 70s New York

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. I'm also grateful that you're here, and grateful to hosts Kousha Navadar, David Furst, and Tiffany Hansen, who filled in for me while I was on vacation. I went on a Nat Geo tour of Morocco. If you're interested in checking out my pictures, they're on iamalisonstewart on Instagram. It was wild.

Coming up on the show today, we'll kick off this month's full bio conversation with Susan Morrison. She's the author of Lorne: The Man Who Invented Saturday Night Live, and we'll learn about the art of taking portraits of SNL cast members and guests with Mary Ellen Matthews, who's been photographing the show for 25 years. Plus, we'll learn about a new installment of the documentary series Eyes on the Prize. That's the plan. Let's get this started with a cinematic look at New York City in the late 60s and 70s.

[music]

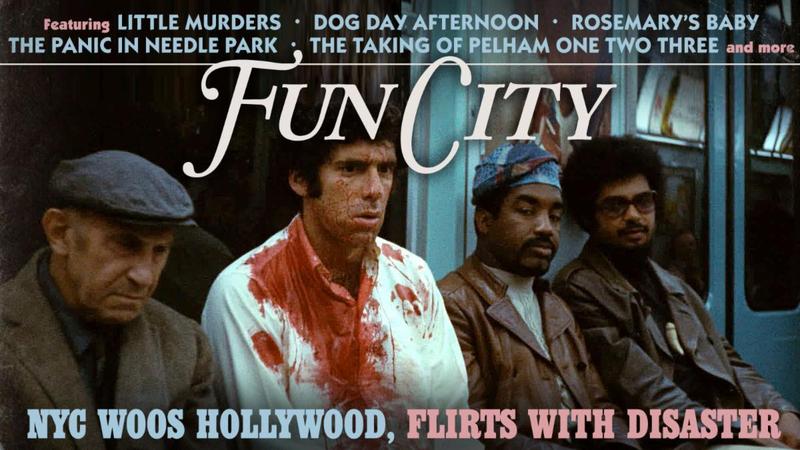

In 1966, New York's mayor, John Lindsay, established the Office of Film, Theater and Broadcasting. The hopes were to encourage artistic and, frankly, economic development in the city. It was a turbulent time for New York, and the movies that emerged from this period reflected the city's grit, danger, opportunity, and resilience. Starting tomorrow, the Criterion Channel is offering a selection of films created here in New York during the 60s and 70s. The series is titled Fun City: New York City Woos Hollywood, Flirts With Disaster.

It includes crime classics like Dog Day Afternoon and The Taking of Pelham 123, blaxploitation films like Cotton Comes to Harlem, and even an unlikely Clint Eastwood western set right here in the city. The series was curated by J Hoberman, a longtime film critic who began writing for The Village Voice in the late 70s. He is also the author of the forthcoming book Everything Is Now: The 1960s New York Avant-Garde Primal Happenings, Underground Movies, Radical Pop.

It'll be published on May 27. The films we'll be talking about today will be available to stream on the Criterion Channel starting tomorrow. I'm joined by J Hoberman. Hi, nice to meet you.

J Hoberman: Hi, nice to be here.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, we want to hear from you. What's your favorite New York City movie from the 60s and 70s? What do you love about movies from that period? We're talking about New York City movies from the 60s and 70s. Our number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can call in, you can join us on air, or you can text that number as well. 212-433-9692. This new film office, in 1966, was established. Who lobbied for the office?

J Hoberman: It really was Lindsay's idea. What he did was, he cut through a lot of red tape. It used to be impossible, basically, to shoot on the street in New York. There were filmmakers who did it, but it was very, very difficult. He made it much easier, and he was totally into this. He made it his thing. He showed up at the various shoots. He officiated over the New York Film Critics Circle dinner one year. In a way, it was like LaGuardia reading the comics.

Alison Stewart: When you think about why filmmakers wanted to shoot in New York, once we made it possible for them to come to shoot, why did they want to shoot in New York?

J Hoberman: Well, the location. You can't build this on a movie set. Once they got here, they really dug into it.

Alison Stewart: How do you think it influenced films that came out of Hollywood?

J Hoberman: Well, I think that probably helped to stimulate location shooting in general. There were other-- something like Easy Rider goes cross country, shooting on location. I think that the New York crime films tended to be tougher, more brutal, even, maybe just in the suggestion, because you're shooting it on these actual mean streets and so on. I think that that had an impact as well.

Alison Stewart: I was so excited when they said you were coming in because I remember you as the critic from The Village Voice. That's amazing. During that period when you were starting as a film critic, what kind of films were you attracted to?

J Hoberman: Well, let me say that first of all, most of the films in this series, I saw as a civilian. They came out-- I was going to movies a lot of times on 42nd street, in the late 60s and the 70s, but when I started at The Voice, I was interested in avant-garde films, documentaries, foreign films from countries that the other critics weren't particularly interested in.

Alison Stewart: You're saying this, that this era of filmmaking is now the stuff of legend, a key cinematic moment that would forever shape the identity of New York. How did these movies shape New York's identity?

J Hoberman: Well, I think that people thought of New York and particularly the neighborhoods where the films were shot. The big location was around 127th street in East Harlem, because that's where the Filmways studio was. They just used the streets around there, and that became New York. Also, shooting on the Upper West Side, which was much grittier than it since became. I think that people got a sense of Manhattan as a tough town, let's say.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a call. This is Jonathan. He is calling in from Brooklyn. Hi, Jonathan. Thanks for taking the time to call WNYC. You're on the air.

Jonathan: Hey, thanks for having me. Mr Hoberman, your book sounds amazing. I can't wait to read it. Yes, it's my favorite era of New York history and movies. A film that has always resonated with me is Midnight Cowboy. I think that dark and disturbing look at the city in the late 60s, and then I think foreshadowing or portending what was to come in the 70s, all of it, the cold desperation, a city falling apart.

What was going on with arts and culture, troubled people being drawn to a decaying city and either being stuck there, as Joe was, or Ratso Rizzo, who could never get out and had never been out. Just how everybody was on their own, almost feral, and having to survive in the city, I think really painted an incredible picture.

J Hoberman: That's a key film. No question about it. It's not in this series, and neither is The French Connection, which is the other key film, because they've shown a lot on Criterion. The point that I would make about Midnight Cowboy, though, is it's shot by a foreigner. John Schlesinger was making his first movie in the US, and this is true of a number of these movies. Half of them were made by native New Yorkers. The other half were made by people from--

Alison Stewart: That's interesting.

J Hoberman: Yes, yes. A bunch of Czech filmmakers. Roman Polanski is Polish, Schlesinger is English. Yes, they had another perspective on New York.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Chris from Brooklyn. Hey, Chris, thanks for calling All Of It.

Chris: Hey, what an honor to talk to two pop culture icons. Hi there. I want to mention the movie Fatso with Dom DeLuise. That was a film that I think captured the tri-state Italian American experience in a crystal clear way, and as a kid, I remember when that first showed up on cable, one of the early cable movies, my family would get together, watch this, and howl. All my aunts and uncles, my mother, just screaming and laughing, and realizing, after seeing it with my wife a few years ago, it is the loudest movie you could ever see.

J Hoberman: You made me want to revisit it. Should mention that Anne Bancroft directed that movie.

Alison Stewart: There you go. Let's talk about some of the films that you curated for this series. My guest, by the way, is J Hoberman. Curated the new Criterion Channel series, Fun City: New York City Woos Hollywood, Flirts with Disaster. Will be available tomorrow. Okay, we're going to talk about Panic in Needle Park. It's about heroin addicts on the Upper West Side. A very different Upper West Side. Let's listen to a little bit of the trailer.

Speaker: The intersection at Broadway and 72nd Street on New York's west side is officially known as Sherman Square. It's called Needle Park. It is here in the neighborhood of Needle Park that drug addicts live, steal, and hustle, and somehow manage to exist from one day to the next. It's here that Bobby and Helen find each other.

Alison Stewart: They don't find each other at the Trader Joe's. Definitely not. [laughs]

J Hoberman: [laughs] But it is a love story.

Alison Stewart: What does this tell us about the Upper West Side of this time?

J Hoberman: Well, it's shown in the movie, like an open-air drug market. The park is a little triangle, between the avenues. They shot it one down from the actual.

Alison Stewart: Oh, really?

J Hoberman: Yes, but still, it's the same kind of thing. No, the west side is just full of junkies, pushers, and hustlers. That's the-- Yes. [crosstalk]

Alison Stewart: Stars Al Pacino, he's kind of a sweet guy.

J Hoberman: Kind of a sweet guy. I would say that in this series, there are two real standouts. There's Pacino, the actor, and Pacino is-- You cannot be more New York than Al Pacino. He's great in this. Very young, but in Dog Day Afternoon, he's mind-boggling. The director--

Alison Stewart: So good, such a good movie.

J Hoberman: The director of Dog Day Afternoon, Sidney Lumet, did his best work shooting in New York. He also has an interesting New York background. His family, they were involved in Yiddish theater. He grew up on the East Side and so on. I think that those guys were, in a way, the stars of this series.

Alison Stewart: Attica. [laughs] Let's talk to Robert, in the Bronx. Hi, Robert.

Robert: Yes, thanks for taking my call. I think one of the most underrated 70s movies, and every time it's on, I got to watch it, is The Seven-Ups with Roy Scheider, Bill Hickman. It just caught that essence. It's a great cop story. A fantastic chase scene through Manhattan. They go over George Washington Bridge and they're shooting scenes over by Little Italy, Pelham Parkway, Co-Op City. I grew up in the Bronx, so to see these places now-- Like you said, there's no Trader Joe's there anymore-- Well, now there's a Trader Joe's there.

Before, it was just this very rough, and it really-- Every time it's on Turner Classic, I have to DVR. I drive my wife crazy. She says, "You saw it." I know I saw it, but it's one of those things where-- I just love those movies, but that one, [unintelligible 00:11:57]-- You get The French Connection, and you get those types of movies, but The Seven-Ups was always just one step below, but I always thought it was the best movie around. Yes, and The Taking of Pelham 123. Can't go wrong with that.

J Hoberman: That's great. Have you seen Across 110th Street?

Robert: I believe I saw it on Turner Classics a while ago, and the Needle Park one was on a few months ago.

Alison Stewart: Pretty good. We've got some other texts here. I think Taxi Driver and Saturday Night Fever are great New York films from the 90s-- from the 70s. Excuse me. We also have Klut. The Warriors. Can you dig it? Let's start with the oldest movie on the list, actually, 1966, You're a Big Boy Now, which is a comedy directed by Francis Ford Coppola. It's about a New York City Public Library employee's relationship with a go-go dancer. How would you describe this film?

J Hoberman: Well, it's kind of a new wave film. Very self-consciously wacky. A lot of locations, really crazy locations. Coppola is a native New Yorker too, I would throw that in, and a youth-oriented film with a-- I'm trying to remember what band did the music for it. I don't think it was the Lovin' Spoonful, but it was something like that, some kind of folk-rock band. Yes, it's an attempt to make an indigenous version of a French new wave film, in a way.

That was the first film. It actually predates the mayor's office. Lindsay intervened in person to allow Coppola, who was a kid, to have access to all these locations.

Alison Stewart: It was Lovin' Spoonful, by the way. Let's listen to a little bit of the trailer from You're a Big Boy Now.

Speaker 2: This is a boy. His name is Bernard. He has a mommy, a daddy, a doggy, and contact lenses. You might say he has everything a boy needs to be happy, but Bernard is not happy. Why? It's very simple. He doesn't want to be a boy anymore. What he really wants to be is a big boy, grown up, a man among men, among women, so one day, while roller skating around the public library, Bernard decided to make the big move. Leave home and make out on his own.

Speaker 3: Don't eat too much. Don't stay out late. Don't--

Alison Stewart: Could listen to that forever. What do you think about this film? What signs does this film show that Coppola is going to be a good director?

J Hoberman: That's a good question. After this, he was-- Well, he made one interesting movie, kind of a road film, and then he got roped into making Finian's Rainbow. I would say that there's not much in this that would lead you to The Godfather, except, I guess, the locations, and the feel for the city.

Alison Stewart: My guest is film critic J Hoberman. He curated the new Criterion Channel series, Fun City: New York City Woos Hollywood, Flirts With Disaster. It features New York City films from the 60s and 70s. It's available to stream on the Criterion Channel starting tomorrow. Listeners, we want to hear from you. What's your favorite New York City movie from the 60s or 70s? Do you like crime movies? Do you want to tell us about a blaxploitation film that you like?

Give us a call. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. Let's talk to Craig, who's calling from Morganville. Hi, Craig.

Craig: Hey, guys. How you doing? A movie that was not New York oriented, but was a spy thriller, but took place in your-- Three Days of the Condor, with Robert Redford. The backdrops of New York at night went into a couple of the projects and some brownstones. The way that you looked at the city at night, looked intriguing, but also dangerous. How they made mundane things that could be arresting, like a mailman with a machine gun, before we knew what going postal meant.

Also Coogan's Bluff with Clint Eastwood, that was also a good New York movie.

Alison Stewart: That's on your list.

J Hoberman: That's on my list. Coogan's Bluff is sort of the reverse of Midnight Cowboy, because here you have a real cowboy, a deputy sheriff from Arizona comes to New York, and runs into all kinds of problems, really. He's getting dissed right and left by all the urban characters, but he prevails, and then he goes back, of course, to Arizona. He's a successful fish out of water, where Joe Buck is not really such a successful cowboy in New York.

Alison Stewart: Are there elements of a Western, like new Western?

J Hoberman: Well, in a funny sort of way, if you consider new-- It's like Fort Apache, the Bronx, in a way, if you consider New York as a place full of dangerous types, primitives, whatever.

Alison Stewart: This is Brian, from Windsor Terrace. He said, "I live on the block where Dog Day Afternoon was shot, and you can still see a few ghosts of the movies on buildings up and down the block. There's an excellent hot dog stand across from the bank, called Dog Day Afternoon. Also, I wanted to plug Harold Lloyd Speedy, which has street scenes from New York City, from 1926. Some of the earliest footage of the city on film. So fun and fascinating."

J Hoberman: I wanted to-- just to come back to the previous caller for a second.

Alison Stewart: Yes, sure, sure.

J Hoberman: When he talks about New York being made as a menacing place. Rosemary's Baby is a great example of that.

Alison Stewart: Never want to go into Dakota after that.

J Hoberman: Or anywhere. Anything could happen to you anywhere. The phone booth by Central Park and so on.

Alison Stewart: I loved Next Stop, Greenwich Village. It was my dream as a kid from Queens to live in the Village.

J Hoberman: Mine too.

Alison Stewart: Also on your list, you have Bye Bye Braverman, from 1968, about four Jewish friends who are carpooling to the funeral of their friend who died young. How does this film-- How does it age?

J Hoberman: Well, I have to say that I love this movie, and when it came out, the reviews are fascinating because they were saying, that's a New York movie and it should stay there, maybe, because it just was considered too ethnic, but ethnic in a very specific way, because the protagonists are four Jewish intellectuals, Partisan Review types or Partisan Review wannabe types, so that's already-- They're making jokes about popular culture and so on, they go on this absurd trip to a funeral.

Yes, I think that it was a sleeper, and that, for me, it still holds up.

Alison Stewart: The Plot Against Harry, a 1969 comedy directed by Michael Roemer. It was filmed in 1969, but didn't have a theatrical release until the 1980s. What happened?

J Hoberman: Well, that's another Jewish joke in a way, as a film. Roemer was a-- he came over as an émigré, came to New York in the late 30s, and grew up here, more or less. He got into independent film. He made Nothing But a Man, which is a terrific independent film from the early 60s. Then he got involved in this other sort of passion project, which is a very funny premise. It's about this numbers guy who is sent up for nine months or something, and when he gets out, he's lost his operation, he's lost it.

He has to try and figure out-- trying to get it back, this and that, in the meantime, he runs into his estranged wife and former in-laws who are welcoming him back into their Jewish family. It's very funny. It's very funny. It's all on location and it's all with non-actors or off-Broadway actors who are having a great time.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Alex who's calling in from Park Slope. Hey Alex, thanks for calling WNYC. You're on the air.

Alex: Yes, thanks for taking my call. By the way, J Hoberman. I grew up reading your reviews in The Village Voice. Thank you so much for all those years. I'm from Park Slope and everybody always told me to watch this film called The Landlord by Hal Ashby, from 1970. Anyway, when I finally saw it, it was just so wild to see parts of the neighborhood back then in 1970, but also still resonates today, about gentrification and racial politics, but it's also really, really weird. That's all I wanted to say. Thank you.

J Hoberman: It's terrific. We wanted to show that, but it was not available.

Alison Stewart: I want to ask you about blaxploitation films. Can you define what blaxploitation films means?

J Hoberman: Okay, well, first of all, the term comes from Variety. Yes. It was an inside showbiz term. The first example is really Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, which was a totally independent production and, in a sense, came out of nowhere. Although Melvin Van Peebles had made movies before and did incredibly well. I believe it opened in Detroit. It just completely knocked the industry for a loop.

Very quickly, Hollywood tried to catch up, with Shaft and Superfly, are the best known, and they have New York locations, but in a way, they're much more Hollywood. There are some good examples in this. First of all, Cotton Comes to Harlem, directed by Ossie Davis, is a very good and, I think, underappreciated movie, which was entirely shot in Harlem. He knows it.

Alison Stewart: The great Ossie Davis, too.

J Hoberman: Yes. Well, he just directed, but he didn't-- Even so. It's based on Chester Himes. It's a very gritty film. It's funny, that came out before the term blaxploitation. It just was--

Alison Stewart: Oh, interesting.

J Hoberman: Yes, it was. It was just an urban comedy, sort of, comedy drama. It then became-- blaxploitation became a kind of B movie staple. Some of them are better than others. I think that Across 110th Street is very strong. Also Black Caesar, which has the James Brown soundtrack and is shot not only in Harlem, but they went across the river and shot some of it in the South Bronx, so that's a very tough film, but there was an audience, and they were making movies for them.

Alison Stewart: Let's listen to a little bit of the trailer for Cotton Comes to Harlem.

Speaker 4: Introducing two cops only a mother could love. Meet Coffin Ed Johnson and Gravedigger Jones, two of New York's finest. Two cops who take charge when an $87,000 bale of cotton comes to Harlem.

[music]

Speaker 5: Tell me something, will you? What's a bail of cotton doing in Harlem?

Speaker 6: A bail of cotton?

Speaker 5: Bail of cotton.

Speaker 7: Now what would a bail of cotton be doing in Harlem?

Speaker 8: Down south, cotton was king.

Speaker 4: Cotton comes a Harlem. It's cops and robbers with a shade of difference.

Alison Stewart: I just had to get that in there.

J Hoberman: Yes. I love the way the guy says Harlem. Harlem.

Alison Stewart: Completely. Yes, let's take another call. Let's call Liza. Liza from Fairfield, Connecticut. Hey, Liza, thanks for calling All Of It.

Liza: Hi. Thanks for taking my call. I grew up on the Upper West Side, and I remember when I was a kid, my dad took me to see Death Wish. Do you remember that movie?

J Hoberman: Oh, yes.

Liza: Yes. Oh, my God. That was the scariest movie ever.

J Hoberman: Yes, why would he take you to see that?

Liza: I know. My mother was very upset. Very upset. That was scary, but that was New York.

Alison Stewart: That was New York.

J Hoberman: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Ron, from Rockland County. Hi, Ron. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Ron: Yes, thanks for taking me on the show. One of the movies that I always associate certainly with New York was the movie Joe, with Peter Boyle, Susan Sarandon. Great movie. Classic scene in Greenwich Village. They're walking through a head shop, trying to-- this underlying plot of trying to find this other guy's daughter. The poster of Nixon on the wall. Joe, in his inimitable way, looks over to Compton, the guy he's walking through the head shop with, and he goes, "If you can't--"

There was a picture of Nixon and it says, "Would you buy a used car from this man?" He looks over to the guy and says, "If you can't buy a used car from the President of the United States, who can you buy a used car from?"

Alison Stewart: Thanks for calling. Let's talk to Nick. Nick, you're going to finish us out. Tell us what your favorite movie is.

Nick: Oh, great. I have a few. I thought of one after I spoke with your screener, that I really loved, which was Law and Disorder, a really strange police comedy that turns into a tragedy. It was the first movie that I saw that I couldn't categorize, with Carroll O'Connor and Ernest Borgnine, and it's all over New York. Well, but then there's also-- Oh, yes.

Alison Stewart: You know what? I'm going to dive in here, because the first thing you told our screener, but that's a fun answer, I'm glad you said it, was Taking of Pelham 123.

Nick: Yep.

Alison Stewart: The Taking of Pelham 123. Why is this so important?

J Hoberman: Well, I think The Taking of Pelham 123, which was-- Lindsay approved that on the way out, because they really needed a lot of loc-- in the subway, and this, and the other thing. I think that it's one of the few, really, that gives you an idea of how hard it is to manage New York. It really gives you a sense of all the things that go into-- like making the subways run, and this and that.

Aside from the fact that it's also very funny in some ways, the collection of people who are trapped on the subway, or-- Has a kind of authenticity, even though it's a wild premise.

Alison Stewart: My guest has been critic J Hoberman. He curated the new Criterion Channel series, Fun City: New York City Woos Hollywood, Flirts with Disaster. It features New York City film from the 60s and the 70s. It's available to stream on the Criterion Channel starting tomorrow. Thank you so much for coming to the studio. It was a real pleasure to meet you.

J Hoberman: For me, too.