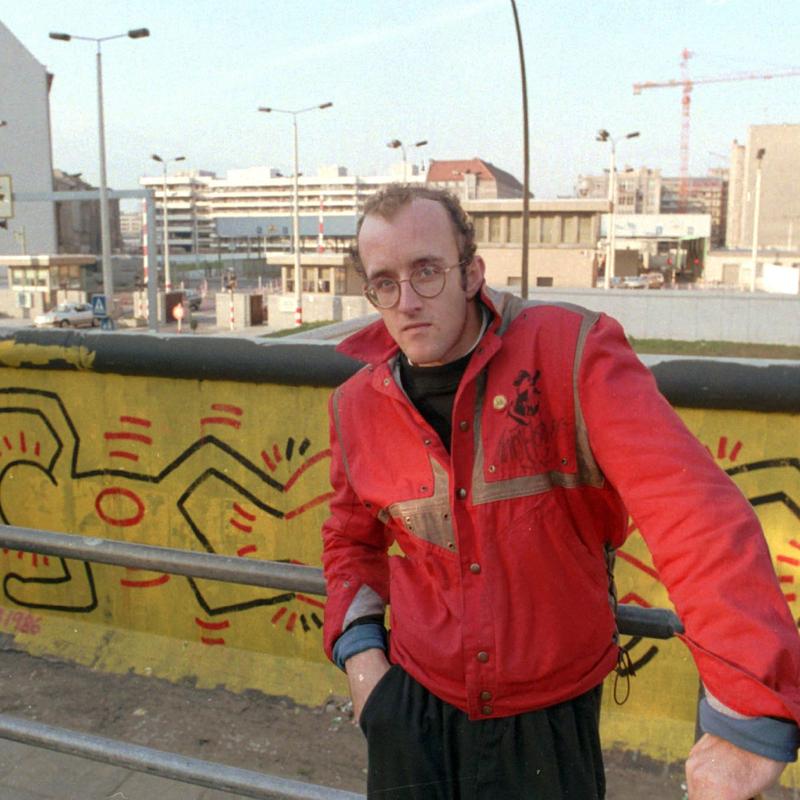

Full Bio: The Too-Short Life of Artist Keith Haring

Title: Full Bio: The Too-Short Life of Artist Keith Haring [MUSIC]

Alison Stewart: Brad, I'm going to start out with the title, Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring. How did you come up with the title?

Brad Gooch: Well, it was sort of a hiding in plain sight title. There were a lot of books, plays, articles about Keith Haring called Radiant Child, Radiant Soul, Radiant Baby, and it's his most prominent mark, tag, or image. Then after about two years of sifting through all these, then the word radiant came to me, and it seemed to be multivalent. I mean, it referred to the work. It also referred to him. I was interviewing his doctor from later in his life when he had AIDS, and he said when Keith walked into the waiting room, he had a kind of radiance. I thought it applied to lots of things at once and covered everything and hadn't been used.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk about his backstory. Let's talk about his parents. Joan and Allen Haring got married because she was pregnant, and that's the way things were done. Were they headed that way anyway, towards marriage?

Brad Gooch: No, they definitely were. They were sort of high school sweethearts, and he had been the designer of the yearbook, and she was a cheerleader, and they had that kind of small-town Pennsylvania relationship going on. She had been, I guess, going out with his best friend for a while, and then they got together. Their life bit this template, I think, from that time, but they stayed together.

I knew them then and interviewed them over my years of writing this book. They were great together, and they had simultaneously a leave it to Beaver kind of cleanness to them. Especially the dad, Al, who I became close with, he was also an amateur artist and cartoonist, and he had gotten Keith involved in drawing when he was four years old. He had a kind of sensibility that could toggle a little bit between Kutztown, Pennsylvania, and then this life that his son created and the legacy that his son created.

Alison Stewart: Keith Haring was born on May 4th, 1958, in Reading, Pennsylvania, raised in Kutztown. What was Kutztown like in the late '50s, early '60s?

Brad Gooch: Well, I sort of recognized that I was from Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, similar. It was very white, and everyone went to church on Sundays as a sort of social event. It was in a part of Pennsylvania that had farms mainly around it, and farm kids would be trucked in to school every day. It was also then this small town that was going through the kind of transition, I think, that happened in the '50s and '60s.

Keith, who then was very much part of being in both those worlds. I mean, in some ways, he was this croquette kid with those round glasses, the look that he kept throughout his life. At the same time, he was really, especially at his grandmother's house, discovering television and then colored television and then cartoons and then Life magazine and reading about 1968 and what was going on at the Democratic Convention. All these influences were hitting him all at once. I think television, if we're talking about his aesthetic, becomes almost the most enduring.

Alison Stewart: His dad had many sides. On one side, he joined the Marine Corps. On the other side, he was an artist. How did he nurture Keith Haring's talent as a little kid?

Brad Gooch: Well, interesting. He would draw with him after supper. This was first Keith in high chair doing scribbles, and then at around age four, doing more drawings. He introduces him then to Dr. Seuss and Walt Disney. Keith Haring later goes on to say that Andy Warhol and Picasso and Walt Disney were the three great 20th century artists. Just there you have a kind of important influence.

I mean, his dad, when he was stationed in the marines in California, would always go to Disneyland. He had a kind of infatuation with it. Keith gained that infatuation pretty easily. I think, also, though, his father didn't just encourage him to mimic these cartoons or do his own Donald ducks, he encouraged him to do original cartoons. That becomes also a big and important kind of influence on Keith Haring because you can really see a lot of that work as original cartoons. He eventually makes up his own imagery.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Brad Gooch. He's the author of Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring. It's our choice for Full Bio. Keith was always into art from the beginning. In the fourth grade, he wrote a note that said, "When I grow up, I would like to be an artist in France. The reason is because I like to draw. I would like to get my money from pictures I would sell. I hope I will be one." Who else saw the vision of himself in this school? Considering to your point, it was a leave it to Beaver kind of environment.

Brad Gooch: It was, but he managed to-- I mean, he had a friend, Kermit Oswald, and they became art buddies. It's interesting how advanced in this environment these kids could be. I mean, they had an art studio, and then the art teachers in the school, I mean, we can all remember one art teacher, and Keith had that purple haired art teacher, and she had a big influence on him. Also, even then, his art teachers noticed that he would not take direction easily. He had an idea what he wanted to do, and he would go ahead and do it, and spent all of his time pretty much in the art room and begins to move beyond just seeing himself as doing cartoony things to having bigger ideas of being an artist.

A lot of Keith Haring is intact from that early Kutztown period, and that's why it's nice talking with you about it, in a sense, because even what you just read, that you have the Keith Haring in fourth grade having a vision of what he wants his life to be, and then pretty much realizes it. I mean, he winds up staying at the Ritz in Paris, using it almost as an apartment away from home by the end of his life, when he's become an international art star.

Alison Stewart: As a teenager, Keith went through a period of intense religiosity. He developed this love for Jesus. How did he show his love for Jesus?

Brad Gooch: That was a really fascinating period. He gets infatuated. It's pretty much the Jesus freak kind of movement at that point. It was a funny crossover of kind of conservative Christian gospel ideas with the hippie movement. He then becomes, as he often did later in life, he becomes obsessed, and he starts putting all over Kutztown these one-way stickers, which is the one way is Jesus and there's an image with the finger pointing upwards.

He's very earnest about this, also very comic about it. I mean, he decides to rate all the Psalms as if they were records on American Bandstand. Also, he believes, and he's influenced by these apocalyptic ideas that the world will end and that we have to do something about it. For that period, which is only about a year, he looks like a character from Godspell and is very much kind of preaching that word.

When he begins to come out of it, moving on to his next infatuation, which is pot and drugs and things like that, he then looks back and says that he thought that a lot of his attraction to that was the imagery, the visuals of it in a certain way, but something always stays with Haring. He's always a bit of a preacher, and he's always kind of naïve and idealistic and taking up causes. At the end of his life, one of his last pieces, is last judgment triptych that he did in Yoko Ono's apartment, and you can see at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine that has the Jesus baby with the radiant lines coming out of it, which we can see in his notebook when he was 16 years old.

Alison Stewart: After Jesus, he discovered a love of drugs. He thought acid seemed to open his mind. What did he think being high did for him in his art?

Brad Gooch: Well, he explains it most clearly in letter to Timothy Leary, later becomes, perfectly enough a friend of his. He had a separate room downstairs. I mean, he was very much a misfit kid in a certain way, revolting, trouble for his parents. Even his Jesus saves that kind of plastering of these signs all over Kutztown was more an embarrassment to them. They were sort of vanilla and chocolate Methodist church going people.

He begins then experimenting with drugs. With acid, he then has this opening up of abstraction, really. I mean, he's writing in a journal, and he starts following this line. It opens him up to the world of shapes and lines, and he sees those same shapes and lines tripping often in the hills around Kutztown, looking up at the sky and the clouds. He has that kind of very hippie redolent moment, but it definitely opens him up also to the idea of being an artist with a capital A. I mean, he really finds his vocation in a different way at that time. He shifts from simply doing cartoons, and even though he's a big Monkees fan, and he did fanzine around it and that kind of art and comic art. He also then begins doing more abstract shapes and experimenting even more.

Alison Stewart: The drugs caused a rift with his parents. Practically, what did the drugs do? Then, really symbolically, what did they do?

Brad Gooch: Well, practically, I just think, as I was saying, these are conservative people. They were shocked and didn't know quite what to do with Keith. Before he went to school, he would be in the little playhouse they had in the backyard, smoking joints. Then he would skip school, and then the school would call, and his mother would have to get him. He had a newspaper route and then he would be stealing things. He got in with this crowd of other pot smoking rebels, with causes or without causes, and going to rock concerts and things like that. This was very troubling to his conservative, button down parents.

His father told me that just made them try to screw the screws more tightly with him. Then I remember his dad said to me, "We discovered later that that was the opposite of the way to deal with Keith." They also didn't really understand what he was doing as an artist. I mean, they didn't see artists as a viable career path, especially at that time, and he always, in some way, I think, resented that. That was the middle of their relationship and caused a lot of trouble.

Then Keith would leave home. I mean, he left home for an entire summer and went to live at the Jersey shore. He was very out there in his need for freedom. I think you could again see this need for freedom in the kind of person he becomes and the kind of career that he has and the moment of gay liberation that meant so much to him when he gets to New York City.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Brad Gooch, Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring is his book. It's our choice for Full Bio. This blew me away. That his early work, Keith Haring's early work was lost. It was on top of a car that took off. How did his work end up on top of the car, and what did that do to him?

Brad Gooch: Well, first he was hitchhiking. I mean, and then hitchhiking again is something that brings back that era to us. He winds up hitchhiking across the country later. At this point, it's the period I was talking about where he escapes to the Jersey shore and he's working a job and he's tripping and he's drawing and painting. At some point, he enters his work in a show. This was on the boardwalk, and he brings basically all that he has to the show and then goes home, hitchhikes home. On the way, the driver decides to change direction. He's not going to Philadelphia any longer, he's turning south.

Keith has to jump out of the car, and he leaves the work behind. Then he realizes what he's done. It's too late. He runs after the car. He never hears from the person again. He never sees that work again. He's very upset. Within a couple days, though, he decides, "Well, I'm just going to do it all again." He does a big amount of work and decides that it's better than what he had before. This also becomes important to him. I mean, not being obsessed with the product in a way, and also having confidence, I think, that he would continue to produce. I think that he always had a feeling that this was all flowing through him, and he really develops.

Part of the reason we have 10,000 works by Keith Haring is that he has confidence that when he picks up his magic marker, something is going to come out. His sister did a graphic book for kids called the boy who couldn't stop drawing. That was her experience of him as his sister. That sort of remains, again, everyone's experience of Keith Haring. He was always working, always drawing, and basically, that's why I call the book The Life and Line of Keith Haring. There's a way in which it's like one single line that he just continues because he's doing it every day.

Alison Stewart: Keith Haring earned money by newspaper delivery, art winnings. He had the idea he would go to the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh. Tell us a little bit about the goal of that school. What happened to students who went there?

Brad Gooch: Well, that was really, in a way, to satisfy his parents. The Ivy school was in Pittsburgh. It wasn't Paris, which was his original plan. It was a combination commercial art and fine arts school. He does go there. It is interesting that it seems so-- Kutztown seemed so unpromising a town to engender a major 20th century artist, but actually, a lot of these Pennsylvania towns were like that. Andy Warhol was from Pittsburgh. Franz Klein was from Wilkes-Barre, where I'm from. Jeff Koons was from York County in the north. Calder was from a town outside of Harrisburg.

Keith goes to Pittsburgh, to this smaller school, not the Carnegie, and tries it for a while. Pittsburgh becomes more interesting. I mean, he drops out of the art school and deciding it's really not for him. He has a girlfriend in Kutztown, Susie, who I spoke to extensively, but interesting about that time, which hadn't really been covered in other accounts of Keith Haring's life, including his own accounts of his life. Those two years I found really interesting, because based on whatever was around him, he was starting to put together his own aesthetic, his idea of what an artist was or what kind of artist he could be.

Part of this is he becomes infatuated with El Lissitzky. El Lissitzky's a European, who has a show that year at the Carnegie Museum of Art. Debuffet is a big influence on Keith Haring. You can still see those blues and reds and blacks, but Debuffet had a big sculpture in the lobby of the Carnegie Museum. Christo, huge effect on Haring in terms of doing public art. There was a showing of the documentary about Christo the year that he was there. You can watch him seeing what's 30 feet away from him and really absorbing it and figuring out how it could be useful to him or what it would mean to him. He eventually has his first one person show in Pittsburgh also, and before he then decides that he needs to go to a real art school, which is School of Visual Arts in New York City.

Alison Stewart: I want to talk a little bit about Susie. He chooses to drive across the country with her, his girlfriend. They follow the Dead. What was it about Jerry Garcia and the Dead that inspired him?

Brad Gooch: Jerry Garcia and the Dead says so much. One, I think it was the approach of the Grateful Dead that they would give away their bootleg tapes, and they had these t-shirts. It becomes part of the engine of their popularity. I think that this appeals to Keith and that it influences, in a way, the way he approaches his own career later. He does do these Grateful Dead t-shirts, and, like, classic deadheads, he and Susie hitchhike across the country, sell Grateful Dead t-shirts at their concerts. There's also something of the fanboy about Keith Haring. He had earlier been a fan of The Monkees television show, and then he was a fan of Jesus, and he's a fan of the Grateful Dead in a certain way.

I think he liked the melding, certainly the psychedelic aspect to it, the utopianism of it, the way in which it was a whole immersive life that was raised up to this by music and style. I mean, all of this appealed to him, and especially as a teenager. His relationship with Susie was fascinating to me. No one had ever talked to her. I interviewed her first, which no one had done, and it was a little bit formal. Then I discovered that she liked to DM on Facebook. New biographers tool, a ping pong game of this DMing over Facebook.

Alison Stewart: Oh, that's interesting.

Brad Gooch: I found out a lot. That becomes a kind of rich period for me.

Alison Stewart: That period was interesting because it was kind of moreover with them. They were in Berkeley and San Francisco, and there's this story where a young gentleman is sort of hitting on him and he clings to Susie, but he recognizes that there's something up. What was the relationship with Susie, and when did he start to recognize that he was queer?

Brad Gooch: Yes. Interesting. I mean, I think that he definitely, again, having kind of grown up in a town like that, in that era and being gay, there's almost like a double kind of bookkeeping that you would do where you're not aware that you were gay, and you were aware of all these urges and attractions that you have. First of all, there was no name for them, particularly. The New York Times wasn't even using the word gay. In Pennsylvania you could be jailed for sodomy. It was a sort of don't ask, don't even think about it kind of atmosphere.

I think he was probably aware as a boy, and he remembered attractions he had had to other boys at camp and in school, but he wasn't completely aware of them. Also with Susie, I mean, it was an authentic relationship they had. She said, 'If he'd been faking it, I would have known." There was a legitimate kind of relationship going on between them and it was based in some way on love of art and she was pretty supportive of him.

During that time, then eventually he starts realizing-- I mean, they sort of come to it together. It's not like he's hiding from her and she discovers it. I think it's that they evolved together to realizing that he's gay, and the relationship frays in that way. Also, he starts then going out to gay bars and cruising areas, mainly Black dance bars in Pittsburgh at the time. All this just becomes together with wanting to go to an art school, he wants to come out. New York City 1978 is a perfect destination for both of those.

Alison Stewart: Before we leave Pittsburgh and go to New York, I want to talk about the mattress factory, what went on there? Because he comes back and he took up work at the mattress factory.

Brad Gooch: Right. The mattress factory, I mean, now is very established kind of environment, art space. At the time, it was just beginning. It was that sort of place where he and Susie could crash, basically, and Keith could have a studio. It's a place for about six months where they kind of get by. Also, Keith is creating work and kind of the right environment for them in experimental bohemian sort of setting in a sliding neighborhood in Pittsburgh.

It was interesting to me when I was there, though, that no one in Pittsburgh seems to be aware of Haring's time among them. I mean, no one knew about it at the mattress factory when I was there. I was in the Carnegie Museum, they have a huge, beautiful tarp, an early Haring hanging, and the posting on the wall says that Keith Haring is an artist from Kutztown, Pennsylvania, who went to New York City and became an artist. They managed to sort of skip.

Alison Stewart: That's really interesting. Reading your book, it seemed like Pittsburgh was a bit of an incubator for him.

Brad Gooch: It absolutely was an incubator for them. Hopefully from my book, people in Pittsburgh will realize this and accent it a little bit more, I would think.

Alison Stewart: In 1978, Keith Haring was dropped off at the Y on 23rd street. It was housing for students attending School of Visual Arts, SVA. He was there two days, I think you said?

Brad Gooch: Yes. First of all, it was the second YMCA he'd been dropped off. First was in Pittsburgh, and then this, the 23rd street YMCA. The year, the season that that YMCA video was filmed there. That's one of the places. The Chelsea hotel was another where you could stay for $80 if you were an SVA student. Keith goes there. He makes his way around day one and one and a half to Christopher Street in the West Village, which he said is like landing in a gay Disneyland. Highest compliment he could give. That was a moment where Christopher Street was teeming, especially on a Sunday afternoon with guys in all sorts of costumes. That's where the YMCA guys came from.

I mean, there were people dressed in leather jackets and people dressed as lumberjacks, and you could walk down to the pier where people were cruising. Keith meets somebody pretty quickly. This somebody takes him back to this house. He's living out on West 10th street in the village, where there's an older guy who has a lot of rooms in his house, and there are a lot of young gay guys staying there.

This becomes his immediate group of friends, and they go to the Y and help him move out, bring all his stuff to that house. The next day, Monday, he starts school at School of the Visual Arts. Shows how fast Keith Haring's life went, and also what that time was like. There was a tremendous excitement. There was a feeling of liberation, and we didn't have social media or cell phones. If you wanted to meet someone, you needed to go out to a club or a bar or a street. There's a lot of intensity among young gay people at the time and Keith just went with that flow.

Alison Stewart: He attended SVA, but he seems sort of unwilling to take the basic classes. What was required of him? Why was he allowed to blow off certain assignments?

Brad Gooch: Well, the reason I mentioned the purple haired teacher in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, when he was in middle school, is that they learned that he wouldn't take direction, and he had an idea about what he wanted to do. When he landed in certain of these required basic classes where you're supposed to paint or you're supposed to do life study drawing, he wasn't interested. I mean, he even said he couldn't do that.

He had already this very strong sense. He was almost like an outsider artist in that way. Very strong sense of what he was going for, even if he wasn't there yet. Instead, then he took a lot of the courses-- SVA had a great faculty at the time, and just from seeing what classes Keith did take and became interested in, you get a sense of the mood of the art world in the late '70s. He was taking video classes, performance art with Simone Forti, conceptual art with Joseph Kosuth.

He had stopped painting pretty much entirely. He for six months was a poet and was reading at the St. Mark's Poetry Project, readings at Club 57. The art school for him, rather than being a painting school, is a place where he's starting to put together, again, these extremes and this kind of collaboration between different kinds of artworks. I think then the real importance for him-- and he drops out again. I mean, he drops out of SVA after two years, feeling that he was beyond it and he didn't need it. It was true. That was its place. That kind of character is admirable, I think, or to me is kind of inspiring that he has his own rudder and he doesn't want to be slowed down.

Alison Stewart: We're discussing Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring. I'm speaking with its author, Brad Gooch. It is our choice for Full Bio. You mentioned the artist Barbara Buckner was somewhat like a mentor to him. What did she see in Keith?

Brad Gooch: Well, she was one of the people in those early classes and who-- at first, they had a conflict because he wouldn't do what he was supposed to do, wouldn't do the life drawings. Then she started paying attention and she would see that Keith would be sitting on a window ledge in the back of the class and go over and see what he was doing and talk to him. I think she began to realize that he was sort of the real thing in that he already had a sense of what he wanted to do. He had his own line and there wasn't any-- she reinvented the sixth-grade art teacher and there wasn't any sense in trying to turn him into something else.

The way she talked about him was he had a golden heart. I think that was also unusual in Keith Haring. Also, Bill Beckley, who taught semiotics class at SVA that was very important to him, said a similar thing. That Keith wasn't ironic. There was a certain kind of earnest, joyful quality that he had and that he kept it. He wasn't trying to be overly clever at that moment. Diego Cortez, who was a curator also and a friend of Keith, told me that when they came to New York, at that time, the art world in New York was mainly white people in white rooms drinking white wine. Now Keith didn't have that sort of attitude. His project then is how to bring his own kind of sensibility in his own world to the art world.

Alison Stewart: He spent time as a poet, and he spent a lot of time as a video artist, which is really cutting edge when you think about the time. What did he want to explore with the video? Sometimes they were suggestive.

Brad Gooch: Yes. I mean, one thing that he was always exploring at SVA was gay liberation and coming out. One of the first assignments that he does was go out and do 21 drawings of one thing. Keith, over the weekend, does all these penis drawings, but it's like penis in front of the Museum of Modern Art. Penis by Gucci's, my own penis, medium, soft, hard, all of these variations. Then he does penis wallpaper. He has that going on his first semester or two at SVA. That's partly a way of coming out. You know we were talking about his parents before?

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Brad Gooch: Interestingly, for someone who becomes an icon of gay liberation, Keith's mother told me that he never said the word gay to them. He never came out in a conversation with his parents. At the same time, he's doing all this sort of out there work. Similarly, at SVA, is doing these penis drawings as a way of flirting with coming out or a way of communicating, telegraphing his identity, but it was never that verbal with Keith, I think. That's an important part of what he's doing.

The video then-- he's interested in life. Especially at SVA and performance art. The video at first are these sexy things like him and different boys together, sudsing up in their shower and bathtub and things like that. Those are the pieces that he would show in class and were shocking to the students at the time. Then he would also do videos of himself, or it was always videos of his friends, videos of himself. In a way that Warhol did when he was doing films, less together as scenarios, he was very interested in recording what was going on. That remains. I mean, throughout his career, he's always playing with, tampering with the world in some way.

Alison Stewart: It's so interesting as you read about his life, because he just-- "Oh, he makes a friend, Kenny Scharf, at SVA," who, obviously, goes on to become a well-known painter. What did Keith think of Kenny?

Brad Gooch: Well, they were very close. I think that Kenny sort of recreates his art buddy relationship he had with Kermit Oswald in Kutztown. Keith wasn't like a private artist. He wasn't in his studio just doing his work. He was always out there. That makes him a good figure for a biography in that way, because what he was involved also was publicly with so much of the art world and the life and the people of his time. He was kind of a fulcrum for it.

Kenny, they find each other. I mean, actually, the description of both, especially Kenny, of SVA at the time, in spite of faculty, was he was kind of disappointed because all the students seemed like they're from Long Island. There was an illustration side to SVA, a commercial side to it, as there had been to Ivy. Early on, Kenny who has come from California, kind of long-haired surfer look, is going down the hall in SVA and sees that someone has a boombox on with Devo, and they are painting themselves into a corner of this room, and that's Keith Haring. Keith is videotaping himself, painting himself into the corner with Devo playing as the soundtrack.

That shows how video worked for Keith, in a way, and how it was both performance and document and artwork. Kenny's immediately, "Oh, this is someone who I want to know. This is why I came to art school." They meet same day. Later that day, Keith is helping Kenny drag television sets that have been left out in the trash from the west Village across town to SVA, which is on the east side, to build a TV sculpture. From that point on, they're bonded in their love of art, their kind of daffy sensibility. They become roommates for a while at Times Square. Very important relationship in that way.

I think that then Keith becomes successful and famous faster than Kenny Scharf, and that becomes a tension between them somewhat, I think more on the side of Kenny, perhaps. Those kinds of things happen. I mean, someone else who he meets at SVA is Jean-Michel Basquiat. This likewise happens in a random way, which he's going into school, someone asks him, this kid, "Could you help me get in? I'm not a student. I want to get by the security guard." Keith does.

Then when Keith comes out of class, he sees on the hallways are painted all these images that Basquiat has been doing on the street under the name of SAMO, these are crowns and cars and cryptic lines of poetry. Keith loves that work. I mean, he really admires it, and it's this kind of poetry and mystery to him. To realize, "Oh, that's that guy." Then they become friends. Then Jean-Michel, Keith and Kenny Scharf, and also John Sex, another SVA student, having changed his name from John McLaughlin, become this crew, in a way, for a while. They all then make their mark and are important in creating the world of that moment and the art world of the '80s.

Alison Stewart: I want to talk about their art world, but there was this-- It's a little bit of a sidebar, but it's interesting is that graffiti artist Michael Stewart was at Keith's apartment the night he got killed in police custody.

Brad Gooch: Right.

Alison Stewart: What impact did that have on Keith?

Brad Gooch: Yes, Michael Stewart death had a big influence on everyone at that time. I mean, it was a scary event. Also, doubly impactful for Keith, I think, because Michael Stewart, who was a Jean-Michel Basquiat type or wannabe in a certain way, and he was coming to a party at Keith's. Keith's then is living on Broome Street. These are very crowded, popular parties. People would ring the doorbell, come downstairs. Keith would let them in.

Michael Stewart comes in. He's with two other people. One is actually George Condo comes, a great artist later, well known artist later, and someone else who had somehow ripped Keith off. Keith sees this person and then sort of decides, "Oh, there's no room right now. It's full," and they leave. That's the night that then Michael Stewart goes, but much later, a few hours later, to the subway to go home and is beaten by police, is accused of doing graffiti which no one has ever seen evidence of. There's also, like, some kind of strangulation happens there. We don't know what kind. Then he dies about two days later in the hospital.

This is a shock to Keith in some way that he feels responsible because he hadn't let him into his apartment. If he had, maybe the night would have gone differently. It's a shock to Jean-Michel Basquiat because he feels, "That could have been me," as another young Black artist. There's a lot of police brutality at that time. There was a cover story in the Village Voice around that moment about police brutality. We sort of romanticized and loved the '70s and '80s and downtown and the creativity of it all, but it was dangerous and tough. Life could be tough.

Alison Stewart: Keith Haring begins drawing on subways, the area where posters are supposed to be. Why was this the way he wanted people to experience art?

Brad Gooch: Well, if you need one bumper sticker for Keith Haring, it would be art for everybody, his phrase. He was always trying to find a way to get art outside of the galleries, those white rooms with white people drinking white wine. When he was at SVA in his semiotics class, and he wrote a paper in that class about art and the way that art is valued, and that the more rare the artwork, the higher the value. Why some artists feel they should only put out a painting a year.

This was the kind of system he's trying to figure out a way around. He was very influenced, of course, by street art. Also at that time, it was a high moment for the wild style of graffiti on subways. That was this spray can painted big bubble letters, acid TV colors, huge scale that the graffiti artists illegally were doing on the outside of the subways. Keith's more art student, the answer, trying to find a way into this, is he sees actually near the subway at Times Square when he and Kenny are living there, these black matte rectangles, which have always been there. These are the advertising panels.

They used to put ads up for Smirnoff, and then after the rental period of a few weeks, they would take it down and put an ad up for Oh! Calcutta!, a Broadway show at the time. Between then you have this soft black matte space. Keith looks at it and thinks, "Oh, it would be perfect with chalk." It looks like a black it to him. He runs up onto the street, buys some school children chalk comes down and draws his crawling babies and barking dogs, basic kind of Keith Haring images, and he likes it. Then he starts doing more.

This becomes also a kind of performance. I mean, people are watching him doing this. Then it begins to be in all the subway station. I remember these, some of them. I mean, being in subway stations downtown, the Broadway, Lafayette station, and also, it's a mystery at this point, who's doing this. There's an article, I think, in The Post called Chalk Man, in which they're calling him chalk man, and they're trying to figure out who it is who's doing all of these. Eventually he starts going uptown, downtown.

These are impermanent. The reason we have a record of them is Keith's friend Tseng Kwong Chi photographs them. Keith will call him up and say, "Oh, I went on the F Train today and I did drawings at 14th street and 23rd and 34th." Then Kwong Chi would get on the train and ride at the front so he could see and then get off if he saw one of these drawings. They eventually, over five years, and goes on for a while, Keith does 5000 of these subway drawings. It's like one of the largest public art projects ever.

Enough that William Burroughs says some point the same way you can't look at a sunflower without thinking of Van Gogh, you can't go into the New York City subway system without thinking of Keith haring. It was no accident that what appealed to him was that this was the place where Madison Avenue was putting its creations, and they were meant to communicate to people and to get people's attention, and he wanted art that was going to communicate to people and get people's attention in just that manner. That was what was really driving the excitement, I think, of that whole endeavor.

Alison Stewart: Keith Haring also worked with other artists. He worked with Angel Ortiz. Who was Angel Ortiz?

Brad Gooch: Angel Ortiz was LA II. When Keith moves further down into East Village, actually, the Broome Street apartment we were talking about, he sees all these LA II signatures around. Graffiti artists had aliases and signatures and styles and very influential Keith. He kept wondering, "Who's this LA II?" Finally, he's involved in a collaborative project, painting in a schoolyard on the lower east side with a group of other artists, street artists. He's sort of asking around, "Does anyone know who LA II is?" One of them, Futura 2000, does, and says, "Well, he lives in those projects over there. I'll see if someone can get him."

Eventually, LA II comes over. Angel Ortiz. He's 16 years old. Small kid. Keith doesn't first believe it's him, and he asks him to draw his signature and he does and then he realizes it. Is very thrilled about this. He then invites LA II to come over to his studio and that they collaborate on a work. At this point, they start doing these collaborations. Keith goes and has dinner with Angel Ortiz mom, just to reassure. She's wondering, because Keith starts selling these works, like the first one, for $2,000 to a psychiatrist. He splits the money with LA II, whose mother is wondering where this money has come from because there's drug dealing going around and things.

Keith comes in and has dinner and explains who he is. Then she agrees. It leads, eventually, Keith actually takes Angel Ortiz to Tokyo with him and they collaborate on paintings and then on sculpture that are done with Dayglo paintings, a lot of these things in Keith's first show. He's always very collaborative. He mentioned a couple of his art friendships with Kermit and with Kenny Scharf, but he's also then creating work with artists like LA II.

Alison Stewart: Yes. Last year or the year before, there was a show in New York of Angel Ortiz's work. You can see the influence that he and Keith Haring had on each other. Some say in the art world, Keith Haring was treated a lot better than Angel Ortiz was treated. Should Angel get more credit?

Brad Gooch: Well, he certainly deserves a lot of credit for what he did and for those sorts of collaborative works that they did together. I mean, I think, it's always difficult with collaboration. I think as far as I know, LA II is always credited in the works that they created together. Who's influencing what becomes a little tricky, but it's certainly true that Keith Haring becomes this giant art star, and LA II has a much more rugged life, I would say.

It's also that this was, for Haring, this was one piece among many, many pieces. He was always evolving and changing his style and also moving very fast. Not to excuse it, but he could tunnel his way through, and a lot of people felt, I would say, burned, not by him directly, but-- and even I interviewed LA II, and he's not angry at Keith Haring, and he doesn't blame Keith Haring. His anger becomes more at the Keith Haring Foundation or at the public reception or the coverage in some way.

I think what would happen, I mean, it happened with Kenny Scharf, different people, was the Keith's flame of fame was so bright that it left a kind of shadow in a way. This had to do with, in the case of artists, there would be envy among these village artists. I mean, there was money that was now flowing in. In terms of these friends around him and especially graffiti artists who he was friends with, they were suddenly, like Angel Ortiz, hopped up into this world of Andy Warhol and rich people and Tokyo. A lot of things.

I know Angel Ortiz wound up dropping out of school at a certain point, and he didn't tell Keith, and this was a problem for Keith in that way. It became a stress test, I think that world. Keith seemed suited in his way. Not many had such, as we were talking about, a kind of monovision about what he wanted to accomplish, but the people who maybe had less equipment to deal with these or less experienced could get burned.

Alison Stewart: Keith Haring chose to work with-- I never get his last name right. Tony Shafrazi.

Brad Gooch: Yes, you got it.

Alison Stewart: Yay. He had quite a reputation. He defaced us Picasso. He went on to become a big gallery owner. I believe it's since closed. What did Keith like about having Tony represent him?

Brad Gooch: Yes, Tony Shafrazi was an interesting choice. I mentioned before that Keith was interested in getting around the gallery system. One thing that happened because of the subway project is this is where all the buzz begins about Keith Haring, so that he doesn't really need to go take his slides around and try to get a dealer and a show. When he has in the first one man show with Tony Shafrazi in Soho, and I think part of his attraction was probably was Tony Shafrazi's outsider status. Keith never agreed with or was sympathetic with Tony's having spray painted Picasso's Guernica during the Vietnam War with a message that somehow, it was an activist protest gesture on Shafrazi's part, who at that point was a young artist also. Therefore, he was kind of an anathema to the art world. Wasn't allowed in the Museum of Modern Art for a while. Keith's going with him is already shows what lane he wanted to be in. The other was that Shafrazzi had this big gallery. It was a new gallery, had the highest ceilings, was the biggest gallery in Soho at that moment and Keith was attracted to that. He was as simple as that, too. He had the scale of it he liked and he liked that it was just beginning and that he could have some of his friends would also be in the gallery. Kenny Scharff was represented by Tony Shafrazi, so that community clubhouse was always important to Haring. I think all those things work together.

Tony Shafrazi it wasn't a one-way relationship. He had a number of important influences on Keith Haring. Certainly he had sophisticated connections and was able to sell his work and bring Inserts people to see his work, but Kenny also was pushing. In the beginning, he was pushing Keith to "Why don't you do paintings?" Keith said, "I hate paintings. I don't want to do paintings. It's too old-fashioned. I don't like canvas," all this thing. It leads Keith finally, he notices this plastic tarps that Con Edison is using to cover their construction sites in the street. He says, "Oh, I could paint on those."

This is before the first show in the gallery of the Shafrazi gallery, painting paintings on this plastic tarp, and that allows him to return to painting. Shafrazi, I said, one of these was in the Carnegie Museum of Art. That's the kind of thing. It happens again later with sculpture that Shafrazi knows there's a little cutout Keith had done of a dog, one of his imagery, on his desk, and he had painted it red. Tony picks it up and he said, "Did you ever think about blowing this up to 30-feet, to a big scale?" Keith said, "Well, I can't do that. I can't do sculpture. I don't know how to do sculpture. No."

Then Tony sets him up with Lippincott, which is an important fabricator who was doing Calder and different artists at the time, Claes Oldenburg, and Keith makes sculpture. A lot of important moments in his life also have to do with this collaboration with Tony Shafrazi, who was an unorthodox dealer, but successful. He did the Basquiat-Warhol show at his gallery, which was so hated at the time, and is now so loved and was shown in Paris, [unintelligible 01:02:54]

Alison Stewart: Keith Haring's first big show, it was a big media event. CBS news covered it. It was wall-to-wall people who came. What was it like?

Brad Gooch: Yes, it was interesting. Not only was the art fresh, but he brought in a new demographic, in a way, to the art world. There were hundreds of these kids who had been doing graffiti and subway art, and so they came to the show. There were established artists, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Francesco Clementi. There were kids, important group for Keith. He had made coloring books, so there were kids coloring on their coloring books. Keith had realized his wish and had a Black DJ lover at that time, Wanda Bose. Wanda Bose was spinning music for this event. In the basement, in black light were all his collaborations with LA2.

I know Charles Osgoode was actually the announcer for that segment and on the news. At the end, he said that the show had sold out for $250,000. Not bad for a 24-year-old kid from Kutztown, Pennsylvania, in that kind of odd voice. That also establishes Keith Haring and, and his influence. I mean, there's an influence in the surface of his work, but there's also the beginning of an influence of breaking down these sorts of distinctions between high art and low art, public art, comic art, street art, political art, and creating more of the world that we live in today.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Brad Gooch. We're talking about Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring. It's our choice for Full Bio. The Rubell's were big buyers of his work. He became obsessed with Andy Warhol. Andy Warhol became obsessed with him. He's living a very different life than he did growing up in Kutztown. In acquiring this fame and fortune, did it change him, and the big question, did he sell out?

Brad Gooch: [laughs] I didn't know that was a big question still, but it turns out it is. In some way, nothing changed him. I noticed when I was reading his journal entries, and I spent a lot of time at the Foundation, and this book took six years to write. The Haring Foundation is in Keith's old studio on Broadway. Going through these early journals and reading his late teenage journals with him and Susie in Pittsburgh and about how he wanted to be an artist and what kind of artist he wanted to be. There was this crazily ambitious, naive, utopian view, and I just thought, how sweet to see an artist as a young man. It's like Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man.

Then, when I came closer to the end and was reading some journal entries, there was also a 22-hour interview with Keith near the end of his life done by John Gruen that I listened to. Then I realized it's the same voice. I mean, you just hear the same idealism. The ambition is it's still outsized, but now, it's happened, so it sounds. "Oh, yes, of course. Why not?" In that way, there's something that didn't change about him, but obviously, his life got much bigger in terms of this kind of fame and celebrity and his infatuation with other famous and celebrated people in a Warholian fashion.

Alison Stewart: Madonna is in and out of his life very much.

Brad Gooch: Very much, sleeping on the couch on Broome Street and singing at his first Party of Life, which are birthday parties he gave to himself every year. The first one was done at Paradise Garage, Black and Latin dance floor downtown. The distinction between gallery show and party is blurred by him. Finally, then later in the decade, he opens a Pop Shop downtown, and here, then he makes this blurring that nobody has really done yet. No artist of that time opens a shop. Even Warhol was nervous about this, that people wouldn't see Haring as a fine artist. They wouldn't take him seriously.

Now, Jeffrey Deist said that Keith invented the new genre, which was the art product or art merchandise. What he wants to do is have a place where he can sell art at price points available to all those kids who came to the show. At Pop Shop, he's selling t-shirts that he thinks of as prints and pins, and, later in the decade, safe sex condom cases. That's the point of Pop Shop. The place itself was immersively painted by him. Leo Castelli, who did a show of his sculpture, said that Pop Shop was itself a work of art, which is true. That the ceiling now hangs over the lobby in the New York Historical Society. Keith got tremendous pushback for this because of the idea that there was a distinction between fine art, high art, and anything else.

The leading critic-cynic about Keith Haring's work at the time was Robert Hughes, who was the art critic at Time magazine. He had been targeting Haring and Basquiat for a while. He wrote about Keith 'boring' and Jean Michel 'basket case.' He said that Haring was a disco decorator, so there was a shadow of homophobia also to this resistance to Haring at the time. There was racism, as Haring pointed out when he called Basquiat 'the Eddie Murphy of art.'

Alison Stewart: Oh, that's great.

Brad Gooch: From, especially East Village artists spray painted 'capitalist' and 'sellout' on Pop Shop. Actually, Pop Shop never made any money. I don't know that it was intended to make money. He then did an annex in Tokyo.

Alison Stewart: That was a big disaster. '86. Yes, '86 is when he opened on Lafayette, and then they went over to Tokyo and then Tokyo because of Tokyo law.

Brad Gooch: Yes. This is that there still is a naivete around Keith Haring, I think. He didn't want to do business with corporations in Japan or with big department stores. He wanted to do what he had done in New York, which was open his little Pee-wee Herman-style store, but there are problems. First of all, he also had a high degree of control over what he did and quality control, so he wanted to control the product, have it shipped to Japan. This was raising costs. Also, he was used to fake Harings. There were a lot of ripoffs of Keith Haring. In Japan, though, it became another level, which department stores and corporations that had wanted to collaborate with him, then just punished him by doing really state-of-the-art reproductions of Haring t-shirts and things and selling them at a 10th of the cost on the corner.

For some reason, everything about Tokyo backfired for Keith. It was a low point for him because Tokyo was his second city. His father had been stationed in Japan when he was in the military, and he'd grown up with all these stories of Japan. He loved calligraphy. Basically saw himself as a calligrapher, where his line expressed his personality. He loved Japan as it was in the '80s with all this anime and toys, so all of this was a great disappointment. It dovetailed with a time in his history and the history of the time of the AIDS crisis really, really exploding during those years.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Brad Gooch. We're talking about Radiant: the Life and Line of Keith Haring. It's our choice for Full Bio. He traveled the world just creating murals all over the place. Could you give us an example of a few places where you would see a Keith Haring around the world?

Brad Gooch: Well, sure. You can see Crack is Wack, which he did in New York on the East Side Highway coming downtown in 180s. That was when there was actually a studio assistant of his who became addicted to crack, which was this fast-moving version of cocaine, almost instantly addictive. He did this Crack is Whack mural in a neighborhood that was especially being hit by drug dealers at the time. That is still there. In Pisa, six months before he died, a large mural called Tuttomondo, which is on the side of a Roman Catholic church, actually, in Pisa, and is now a draw, a destination. There's the Leaning Tower and there's the Keith Haring mural. The problem, a lot of these have to be restored. One was restored recently in Amsterdam that he had done on the side of a book building. He did in Barcelona an AIDS activist warning. He did these warning murals. There was always where there is often with Haring, a political activism or artivism kind of messaging.

Alison Stewart: Yes. I want to ask you, when did he begin to take on political and moral issues?

Brad Gooch: Well, again, always. When he was twelve years old, he was at the first Earth Day celebration on the campus of Kutztown University. Three Mile Island happened near Kutztown, this nuclear near disintegration, and so he took on anti-nuclear proliferation early on. That was one of his themes. Certainly racism, apartheid, gay liberation, later AIDS activism. He was very active during the two Reagan campaigns of '80 and '84. The second one turned over his downtown subway gallery to get out of the vote into anti-Reagan cartoons.

He wrote in his SVA journal, "The message is the message," and that was a response to Marshall McClellan, "The medium is the message." Basically, he wasn't ironic as an artist and he also wasn't fussy about what surface he was working on. He was very interested in message and in communication. One of the best shows of Haring's work after his death, I think, was in San Francisco Museum of Art. It was called The Political Like. He was often using his line to get people to be aware of safe sex, for instance, different causes.

Alison Stewart: When did Keith Haring become an activist for AIDS?

Brad Gooch: In some sense, he was always aware of AIDS and has some messaging about it and certainly the safe sex. In 1988, in Tokyo, again, he discovers these red spots on him, which turned out to be Kaposi's sarcoma, which was an opportunistic cancer, one of the many under the umbrella of AIDS. He comes back to New York and is then officially diagnosed. He always suspected he was, as being HIV positive. Interestingly, I was very interested in this part of the book, having been around at the time. Many people died of AIDS, but people could die very differently of AIDS, I mean, both medically and in terms of their attitude.

Keith, from the beginning, again, had his own process. He almost immediately comes out, does a rock star move in Rolling Stone magazine and a big interview, and he comes out as a PWA, a Person With AIDS. This is when Rock Hudson was sick with AIDS and was denying it. When Donald Trump's lawyer, Roy Cohn, practically came back from the grave to say he had kidney cancer or he had pneumonia. Obituaries at the time, rarely gave AIDS as the cause of death. Long-term companions rarely were noted, and so Keith goes against that, and that encourages people, I think. He then also turns his art over often. He did Silence Equals Death paintings. He did posters.

He then was also very active in ACT UP, the organization that Larry Kramer had started the main activist political organization at the time. Peter Staley, who was the treasurer of ACT UP, told me that he used to go to Keith's studio, and Keith would give him these brown paper bags full of cash, like $10,000 of cash. Peter would go and put it in the ACT UP account in Citibank on LaGuardia Place. Also Peter told me that in 1989, a third of the receipts of ACT UP were covered by Keith Haring, which no one knew. That part was under the radar, but he was very much with whatever he had and directly activist on the issue.

Also inspiring as coming out as a PWA, but also, he didn't melt away in terms of his work. He did more and more and more and more art and traveled to more and more and more places. I mentioned the mural in Pisa that he did about six months before his death. Three weeks before he dies, he does The Last Judgment triptych I mentioned in Yoko Ono's apartment. He's never in the hospital. He only has really three weeks where he's in his bed and on his deathbed is drawing his Radiant Babies until it becomes too frustrating and he can't finish it. I think Kenny Scharf has the last of those drawings. In many ways, he rose to the occasion and inspired people.

Alison Stewart: I was going to ask you, what can people learn from Keith Haring's unfortunately short life?

Brad Gooch: I think he had to 'use whatever you have' thing. I mean, he said, "You use whatever comes along." I think that I find that attitude great. It explains his own DIY response to life. He would be working on whatever surface was available. I mention he was active during, especially the second Reagan election in 1984, which was a landslide and seemed predetermined. Who was Keith Haring but a guy with some chock, but it didn't stop him. He and Jenny Holzer did these Get Out the Vote trucks and things. I think just the way in which he sponged up whatever was available around him and then spun it into something else and his desire to always kind of enhance people's lives visually and otherwise, I think all of this is something that you can personally be inspired by.

He wasn't waiting around for inspiration, and he wasn't waiting for anyone to give him permission. That was something that Kenny Scharff told me about SVA. Like, you couldn't open a broom closet where there wasn't something by Keith Haring or the way that he met him, painting himself into that corner. He didn't have a license to do it. He didn't ask per diem, and so that quality is always encouraging.

Alison Stewart: Brad Gooch is the author of Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring. Thank you so much for spending so much time with us, Brad.

Brad Gooch: This was great. I enjoyed our conversation, thanks.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.