Full Bio: Lorne Michaels and the Creation of SNL

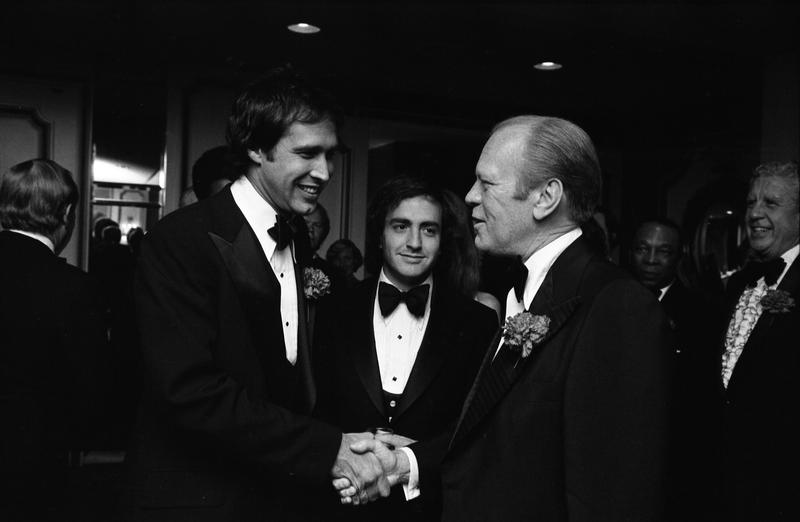

( Courtesy U.S. National Archives and Records Administration )

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. We have some great theater conversations coming up on the show later this week. On Thursday, we'll speak with actor Molly Osborne. She plays Desdemona in the new production of Othello that's now on Broadway. On Friday, we'll be talking about the gripping and hilarious new play from Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. It's called Purpose. It stars Harry Lennix and Jon Michael Hill. The three of them will be in studio to discuss. That's in the future. Now let's get this hour started with the backstory of the man behind Saturday Night Live. [music]

Alison Stewart: Full Bio is our book series where we discuss a fully researched biography for a few days. Our guest is Susan Morrison, the author of, Lorne: The Man Who Invented Saturday Night Live. Susan Morrison got Lorne Michaels to agree to talk to her for the 600 page bio, as did members from Michaels' past and present. Lorne Lipowitz became Lorne Michaels as he launched his career as a writer and a performer, but he showed early aptitude as a producer. He wanted to produce a show that was cerebral and unconventional. Here's Michaels talking to the Today show about the original ethos of SNL.

Lorne Michaels: What had happened then was most of the established institutions had been discredited. That change led to people not knowing where or how to trust. So it was more important to try and be an honest voice. Our job is mostly to entertain, but to do it with a level of intelligence.

Alison Stewart: He got his chance when The Tonight Show host, Johnny Carson, announced he didn't want to do a show that would run on the weekend. The book details the beginnings of SNL, how it ended up at 30 Rock, how he managed the brass, where he found the talent, how the talent dealt with each other, and how Michaels walked away after five years on the show and discovered it wasn't pretty out there. Let's get into it with Susan Morrison, author of, Lorne: The Man Who Invented Saturday Night Live.

[music]

Alison Stewart: Johnny Carson didn't want to work the weekends. What were NBC's options at the time?

Susan Morrison: Well, Carson wanted NBC to take his reruns off of Saturday night so that he could take a day off during the week. I think he probably expected that NBC would just put on a late movie or let the affiliate stations around the country just fill that hour however they wanted to. There was a really dynamic young president of NBC at that time named Herb Schlosser. He doesn't get enough credit for all of the visionary things he did at NBC. Even before this, we're talking 1975 now. He had put on the air a lot of shows about and created by African Americans at a time when that was really unusual. Sanford and Son, Julia, starring Diahann Carroll.

He really had a lot of vision for what television could be. So he said, "Look, we have this time slot, let's do something really creative with it." He dictated a memo about what he wanted on Saturday at 11:30. A lot of people don't realize that he dictated so many of the really precise details of what SNL would become. He wanted it to be live. He wanted it to be done out of New York City in Studio 8H in the RCA Building. He wanted there to be rotating hosts. He had this idea that if they did something like this, it could be used almost as like a farm team to spin off other shows in prime time. Really, just a very innovative set of ideas there.

It just so happened that a lot of the things on his list were the same kinds of things that Lorne Michaels was envisioning in the fantasy variety show inside his head. The one thing that Lorne wasn't sure about, and this was a big surprise to me, and I think really interesting. When they offered him this gig, he almost said no, because he wanted to stay in Los Angeles. This is a guy who grew up in the frigid [chuckles] Canadian climate, and he was really digging living in L.A. He loved the beach and he loved the desert, but he also liked what he described as the way California valued the aesthetic of fun, as a value in its own right.

He knew that in 1975, New York City was on the brink of bankruptcy, crime was up. I mean, he'd seen Taxi Driver and all these other-- Escape from New York and The French Connection and all these movies about New York in tatters. He thought, "Gee, maybe it's nicer just to stay here in my room at the Chateau Marmont."

Alison Stewart: [chuckles] Once he was approached about the job, how did Lorne Michaels feel about sharing the space with NBC's Dick Ebersol, who was also a part of this equation?

Susan Morrison: Well, Dick Ebersol was a very young executive at NBC who had been tasked with finding the replacement for the 11:30 slot on Saturday night. He met Lorne when Lorne was working on The Lily Tomlin Specials, and really starting to kind of see some concrete results from these visions he'd had in his head for a while. Ebersol was a real-- he was a real NBC company man. He's somebody who had rapport with the higher ups. He could talk to the executives. He was a very useful go-between with the network. Lorne saw him as a useful partner in the same way that he thought Hart Pomerantz was a useful partner back in the '60s.

As the show got underway, as often happens, there was some tension because Lorne was clearly the creative mind behind the show. As the show was getting a little bit more successful, Ebersol seemed to be wanting to take a little bit more creative credit than most people at the show thought was warranted. It was almost as if he wanted the world to think that he was the co-creator of the show, when in reality he was the network executive who facilitated the show getting on the air and was supposed to be responsible for budget issues and running interference with the network.

There was a little bit of creative tension. After five shows, Lorne successfully, Lorne and his manager, Bernie Brillstein, successfully got NBC to remove Ebersol from SNL and kind of give him one of these promotions that seemed like was a promotion, but not really a promotion. Basically got him out of Lorne's hair.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Susan Morrison. We're talking about her book, Lorne: The Man Who Invented Saturday Night Live. It's our choice for our Full Bio. Where did Lorne Michaels go to look for cast members?

Susan Morrison: Well, in the beginning, he was determined that everything about his show be different from everything else on television. He didn't want anyone who had ever been on television before. He had this faith that there were a lot of people out there like him and Lily Tomlin, who wanted to make a name for themselves, but also weren't interested in conventional television. He went to clubs, catch a rising star. He found Andy Kaufman, who wasn't in the original cast but was a regular on that first season. If you've never seen Andy Kaufman, go to YouTube right now [chuckles] and watch him.

He really telegraphed the kind of out there, almost arty ambitions that Lorne had for his show. When he first saw Kaufman at a comedy club in New York, one of his friends, Gary Weis, said, "Man, this could be at the Guggenheim." It was so beyond. So post punchline. [chuckles] Really, he got some people from The National Lampoon Radio Hour, he got some people from Toronto, people who he'd done comedy with before. He met Chevy Chase waiting in line to see Monty Python and the Holy Grail. One thing that was interesting is that because his show was on in late night, the pay scale was going to be very low. Two people he wanted, he almost lost.

One of them, the writer Alan Zweibel, who had been-- he was basically slicing cold cuts in a deli at the time that Lorne saw him doing a stand-up set. He almost didn't take the job from Lorne because he had been offered a spot writing the jokes for Paul Lynde on Hollywood Squares.

[laughter]

Susan Morrison: A pretty corny job, but it was prime time, so it was going to be a bigger paycheck. Anyway, it was interesting that he wanted to find these very cutting edge people, but he couldn't offer them a lot of money. They just had to be in on the renegade spirit of what he was going after, and he did find those people, and they made history.

Alison Stewart: Your book is full of so many stories about those early days, it's hard to pick one. You have Chevy Chase thinking that he was bigger than the show, Belushi behaving badly to himself, Gilda Radner suffering through anorexia. There were drugs everywhere. I'm going to ask you to offer one story that shows what it was like to be Lorne in a decision making role and the choice he made.

Susan Morrison: Yes, Lorne, from the very beginning, I think had a very intuitive grasp of management. He never read management for dummies or anything like that. I think it-- just something in his background, being the fatherless boy, [chuckles] he intuitively knew how to handle creative people, I think. There is a story that I didn't know until I was researching this book that I think illustrates that. He wanted to have a Black writer on the staff, and someone he knew at the Writers Guild sent him some material by Garrett Morris, who was older than the rest of the gang.

He was in his 30s and he was a Juilliard trained playwright. So he hired Garrett Morris to be on the writing staff. After a few weeks, an incident happened where something that Garrett Morris was just talking about conversationally, one of the other writers wrote up into a sketch. A writer's room is a kind of a big free for all. Somebody mentions this, somebody else writes it up, but it was a new enough thing that the protocols hadn't been established. Garrett Morris was incredibly offended and felt that his idea had been stolen and went to Lorne and complained and just, "This is a problem."

Lorne, who didn't-- generally, his management approach had been sort of like a parent who wants the kids to sort out their squabbles themselves. So he did not intervene, but what he did was he figured, "Okay, Garrett Morris is someone-- a big talent who we want on the show, but how do we get out of this complicated mess?" Instead, he said to Garrett, "Why don't you audition to be in the cast?" Which is what Morris did. He went to the cast auditions, he auditioned, and he was part of the cast, so he got to be part of the project. This big squabble with the other writer was sort of blown over, and Lorne didn't have to get his hands dirty. I just think that's a good illustration of how he would sort out a mess.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Susan Morrison. The name of the book is, Lorne: The Man Who Invented Saturday Night Live. I want to ask about Bernie Brillstein. He was a talent manager, he had many people on the cast who he represented, Dan Aykroyd, Gilda Radner. How did he cause Lorne an occasional headache? Because I think he was Lorne's manager, too. Right?

Susan Morrison: Yes. Lorne met Bernie Brillstein when he was working on The Beautiful Phyllis Diller Show. Lorne, ever since his father died, he had liked, he gravitated toward slightly older guys. Who had been around, who had wisdom to impart about show business. Bernie Brillstein was one of these guys. He was a big, barrel-chested person with a beard. He was always described as a Jewish Santa. He liked Lorne, and he signed him. There was nothing cutting edge about the acts that Bernie Brillstein represented. Lorne was probably way out there in terms of being edgy compared to anyone else that Bernie had. Again, Lorne was so canny about who he surrounded himself with.

He always felt that it was really good to have Bernie Brillstein as a gut check. He represented middlebrow taste. If Bernie Brillstein liked it, they would like it in Kansas. He was a guy who watched football on Sunday. Something that Lorne didn't really do. He also, he had Lorne's back. He was the kind of person who would get into scrapes, have confrontations with people, that Lorne didn't want to have, because Lorne is by nature unconfrontational. Now, he was Lorne's manager, and in the early days of SNL, he quickly signed up Chevy Chase, John Belushi, Gilda Radner, eventually some of the writers.

That worked pretty well as long as they were all a big, happy band, but as time wore on, it was a little bit complicated for Lorne because, for instance, in the fourth season, Brillstein was the executive behind The Blues Brothers, which is a movie that his clients, Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi were making. That was great for him, he got to have his big Mr. Hollywood moment, but it wasn't so great for his other client. You might say his more important client, Lorne Michaels, who employed those two guys. By setting up The Blues Brothers deal, Brillstein effectively robbed Lorne of two of his most important cast members.

A lot of people always said along the way, they didn't understand why Lorne didn't get madder at Bernie after things like that, but I think he has a real ability to be able to compartmentalize, like, "Well, this is business. It's just business." That's what you're going to do if you're a businessman. You're going to make that deal. Yes, those kinds of conflicts of interest popped up here and there, but I think in the end of the day, Lorne always valued Bernie because he was there at the beginning. That kind of longevity, that kind of loyalty that goes, you know, spans decades, always counts for a lot with him.

Alison Stewart: In your chapter, Into the Wilderness, you write about the time that Lorne Michaels left SNL. It was after the fifth season, or he was kind of pushed out. I couldn't quite tell. [chuckles] How would you describe his leaving?

Susan Morrison: Well, he had been doing SNL for five years. He was absolutely shattered with exhaustion. He had lost most of his cast members. He wanted to keep going, but he said to NBC that he needed at least six months to regroup. He knew he'd have to hire all new people, and he just needed to rest. I think he felt pretty confident that they would do that, because he, after all, had created this show, but he wasn't that sophisticated in some ways about network politics. The network came right back at him and said, "No, no, you can't do that. We've already sold all the fall ad spots. The show has to go on as planned."

He entered into this complicated negotiation, which got sort of fraught, but I think he was persuade-- he thought that he was going to prevail and then something happened right before his final meeting with the president of the network, Fred Silverman, who was not his closest ally. Where on an episode of SNL, Al Franken went on Weekend Update and did a bit making fun of Fred Silverman, the NBC president, for having a limo. The name of the bit was Limo for a Lame-O. Basically, Franken asked all the viewers to send in a postcard addressed to Limo for a Lame-O, saying that if Fred Silverman had a limo, Al Franken should have one, too.

Now, it's Lorne Michaels' practice to not get in the weeds of his writers' and cast members' comedy bits. He would not have told Al, "Just don't do that. I'm negotiating with Fred Silverman right now." It is kind of remarkable to think about that. This thing went over the air, Fred Silverman was completely furious. The negotiations sort of sputtered out. I think Lorne still thought that he was maybe going to be able to save it, but then suddenly, when he was out of town a few weeks later, he got a call saying that NBC had just announced a new producer.

He was shocked, because I think he thought that if he weren't going to do it, that NBC would just take it off the air. He thought it was really his baby, but he was wrong. It was NBC's property.

Alison Stewart: I want to back up one thing. Why did Lorne lose so many cast members in the first five years?

Susan Morrison: Well, when he started the show, first of all, he didn't expect that the cast was going to be as important as it was. I think he almost thought of them as background players. You'd have the star hosts and you'd have these fancy rock bands, but the cast was enormously talented and people loved them. They especially loved Chevy Chase. I think he became famous first because he looked into the camera every week and said, "I'm Chevy Chase and you're not." So he became a giant star in the first season. He was getting all kinds of movie offers.

It also sort of upset the emotional ecology of the show. There was jealousy and rivalry. Why was Chevy Chase on the cover of New York magazine and not them? At the end of that first season, Chevy left because Hollywood was calling. At that point, or even today, if you're an actor trying to make it and you're suddenly getting movie deals and tickets to L.A. on-- first class tickets to L.A., you're generally going to go. When Chevy became a star, the others started thinking, "Well, gee, what can I get out of this?" Belushi was the next one whose ambition really kind of took hold of him.

He starred in Animal House, which was a movie that Lorne wasn't connected with, but was a massive, massive hit. He was suddenly gigantically famous, and so he wanted to pursue the movies. He and Dan Aykroyd, his friend from the show, had developed this act called The Blues Brothers. That was then made into a movie. So basically, it's a pretty classic trajectory, people leaving TV for the movies when the movies beckon. I don't think Lorne had counted on it at that point. It made it hard for him to do the show. The show as to have it be as good and as funny as he wanted it to be.

He hadn't figured out, by that time, that the way to do Saturday Night Live, and certainly the way he's made it happen for 50 years, is that it has to exist in a constant state of renewal. He often compares it to a sports franchise. You have your stars, but you have to have your rookies on the bench. It's also, it's a little bit like New York City itself. It's in a constant state of being torn down and rebuilt. It's one of the things that accounts for its unevenness. It's sort of like the Dow or the Yankees. There are good years and bad years.

In the first five years, it had never occurred to him that he was going to have to be constantly looking out for new talent, constantly hiring people. So when he came back in 1985, that's what he had learned. You have to keep rejuvenating the show.

Alison Stewart: What did he do in the years he was gone from SNL?

Susan Morrison: Well, that was interesting. As I said earlier, he was obsessed with Mike Nichols and always thought that he wanted to make a movie like The Graduate. After five years at SNL, he thought, "Well, the TV part of my career is done now. Now I'm going to go into the movies." He made a deal with MGM to produce and direct movies. He hired a bunch of his SNL writers, including Franken and Davis, to write scripts, but nothing really happened with them. Part of it was that MGM, at that point, was in sort of financial freefall, so they really weren't in a position to make any of Lorne's movies, but he also didn't really know how to do it.

One movie got made in that period called, Nothing Lasts Forever, directed by Tom Schiller, who had made charming little films in the first five years of SNL, but it was kind of like a little black and white art film. I think the studio was expecting a sort of boffo big ticket comedy like Animal House. There's Lorne, he was working on a script, which was an adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. He had optioned Don DeLillo's White Noise. The movies in his head were not movies like Animal House. So that was basically a disastrous five years. I mean, he did-- this is how I met him.

In 1983, he signed with NBC to do a prime time variety show modeled on SNL called The New Show. I was an assistant on that show, which is how I got my foot into this crazy Lorne world, but that show also was a disaster. Really, it was because it wasn't live. It was shot on tape. He would amass several hours worth of stuff and then had to stay up all night editing it and it would air the next day. The value of The New Show was that it made him realize what his talent is.

His talent is doing things live, with a kind of knife point of adrenaline and energy. Anytime you're sitting in an editing room chopping things up and doing them 18 different ways and adding a laugh track, you're going to sap all the electricity, all the energy from it.

Alison Stewart: Once Lorne returned to Saturday Night Live, what changed about him when he came back?

Susan Morrison: Well, he got pretty banged up during the five years of hiatus. By the time he came back to the show in 1985, he had had to remortgage his apartment, he was in financial distress. He really wanted to get it right. The first year, he made a colossal mistake. He decided that he needed to get really young people for the new audience. He hired several people who had starred in John Hughes teen movies. Anthony Michael Hall, Robert Downey Jr., and these guys, they weren't like ensemble comedy players. They were sort of too young and not really seasoned enough to be able to do what SNL did best, which is sort of ensemble work with other really funny people.

That season fell completely flat. He fired almost everybody at the end of that season. The three who survived were Jon Lovitz, Dennis Miller, and Nora Dunn. The next year, he went back and hired people out of comedy clubs. That's when he hired, I think, one of the best casts the show's ever had. You had Dana Carvey, Jan Hooks, Kevin Nealon, Phil Hartman. These people were just amazing actors. Of the first terrible year with all the young people, Al Franken, who was the writer, producer on the show, he said you couldn't even do a sketch about a Senate hearing that year, because these guys, they barely had to shave. They were just too young.

Alison Stewart: Tomorrow, on Full Bio, we'll learn about Lorne Michaels' highs and lows as a producer.