A Graphic Memoir About an Environmental Advocate

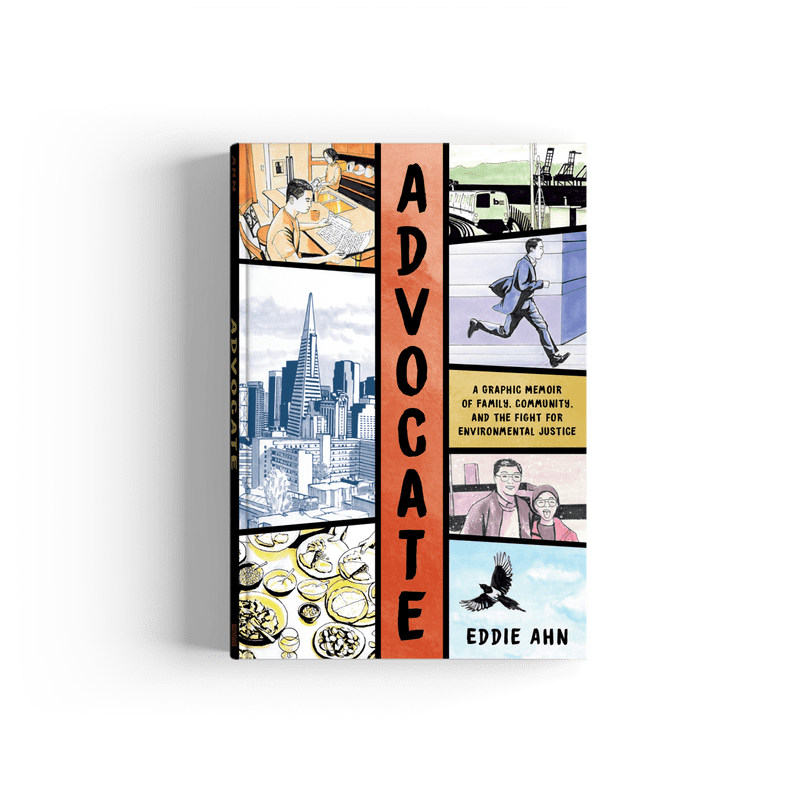

( Courtesy of Ten Speed Graphic/ Penguin Random House )

[MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Citysong]

Kousha Navidar: This is All Of It. I'm Kousha Navidar in for Alison Stewart. Hey, thanks for spending part of your day with us. I'm grateful you're here and happy Earth Day 2024. Coming up on today's show, we'll be spending an hour talking with someone who has dedicated their life to environmental justice, and then opening up the phones to see what you listeners are doing in your own lives to lessen your carbon footprint and reduce waste. Wirecutter's sustainability editor Katie Okamoto will stop by with some tips and we'll take your calls.

Then a new memoir explores the life of a sociopath in her own words. Author Patric Gagne, a former psychotherapist herself, is going to join us to talk about her story. Plus, we'll speak to Christine Yoo, the director of the documentary 26.2 to Life. The film focuses on a group of inmates in San Quentin Prison who take on a massive challenge. They run a full-length marathon within the prison's borders. All right, that's the plan. Let's get this started with environmental justice attorney and author Eddie Ahn about his new memoir and graphic novel advocate.

[music]

Kousha Navidar: In honor of Earth Day, we're starting off the hour by talking about a new graphic memoir that illustrates one man's path to becoming an environmental justice attorney and a nonprofit leader for 15 years. Eddie Ahn draws us into his world, I mean that literally, navigating his heritage, his family dynamics, and the relentless pursuit of justice. That makes this book, Advocate, more than just a memoir. It's really a call to action.

By illustrating his experiences, Eddie's also shedding a light on the need for environmental justice in communities we often overlook that are facing urgent issues. We're talking about wildfires, drought, all brought on by climate change. Eddie joins us today to discuss his new book, Advocate: A Graphic Memoir Of Family, Community, and the Fight For Environmental Justice. The book is out now. Eddie, welcome to All Of It.

Eddie Ahn: Thanks for having me. It's exciting to be here.

Kousha Navidar: Absolutely. It's exciting to have you. You wear a lot of hats. I think that's something that you get when you read the graphic memoir. You wear all the hats pretty well, if I can say, especially being an environmental advocate. What does that label mean to you? How does it show up in your life?

Eddie Ahn: The way I've done environmental activism is through typically nonprofit work. It's been my career for over 15 years now. The work that I do today for environmental justice nonprofit called Brightline Defense is both global in terms of the actions that we take, and also hyperlocal in terms of its accountability. It's often with the lens of something even more specific in the environmental movement called "environmental justice," which is the understanding of the environment in terms of the economy, race, identity, and all the sacrifices that are inherent in global climate action itself. It's been fun to do and have been keeping at it for some time. The actions that we often do range from California-based state policy to even DC-based advocacy in various sectors.

Kousha Navidar: Another thing that you've been at for a long time, another part of that, the hats that you wear, is art. You've said yourself in your book, you've developed over a long period of time, your art. How did you learn to draw?

Eddie Ahn: Oh, it's a very hard-earned scale. I started in college drawing for the school newspaper. It was a daily comic strip. After graduating from college, I kept up the practice while doing nonprofit work, while going to law school. I used to publish fiction stories. These were essentially self-published zines, cheerfully hand-stable by myself and tabling at independent arts festivals across the country. Transitioning to this space has been a whole journey onto itself over the last four years. Originally started publishing more autobiographical comics on Instagram and they really took off there on the space. Then now, it's been picked up by Penguin Random House and released as a wider release.

Kousha Navidar: That's wonderful. The reason I bring it up is because the thrust of this project that you've done, this graphic memoir really felt like threading the needle between all of the different elements of your life and using that as a lens to talk about not just environmental activism, but also heritage and identity, many other things. The question that I brought up for me was why tell this story as a graphic memoir? Here's what I mean by that specifically. What's something the illustrations help convey that words alone can't?

Eddie Ahn: I think the visual impacts of climate change alone are fairly unique. The book even ends on a scene from the California wildfires where the sky itself is a fury orange. You can write that out in text, but it's another thing to just see it. Then the other reason why I love comics and graphic, even graphic memoirs nowadays is a medium, is the ability to juxtapose both text and the visuals together, as well as panels against each other too. To move a story from panel to panel is its own kind of skill. It's been interesting to see how the reactions to something like that is very different than, say, an academic textbook describing climate change.

Kousha Navidar: Tell me about that a little bit. What do you mean by that? Can you give a specific example of the reactions that you've been getting that are different?

Eddie Ahn: The interpersonal play between my professional life and then the service even understood in the context of my family has been very different. My parents, for instance, immigrated from South Korea to open up ultimately liquor stores in Texas and that was a family business. The book itself describes a lot about the transactional worldview that was created from that experience where, literally, their business was measured by dollar sold and a bottle passing over a counter.

To do something like nonprofit work and to work in a sphere like environmental justice, which was not well-understood, I would say, even 10 years ago or even five years ago, it's been a lot to get to the stage where my parents, for instance, will understand what I do today. Comics has allowed me to juxtapose the two ongoing themes of my belief in the service and activism and wanting to address climate change and also their own belief in wanting me to preserve my own well-being and take care of myself. It comes from a good place at the end of the day, but it's always been a conflict that's grown over the years.

Kousha Navidar: Let's dive into that background a little bit because it is hand in hand with, I think, your perspective on environmental justice today. Listeners, if you're just joining us, we're talking with Eddie Ahn, who's an environmental justice attorney, nonprofit worker, also published artist. The graphic memoir is Advocate: A Graphic Memoir of Family, Community, and the Fight for Environmental Justice, which is out now.

Eddie, you mentioned South Korean-born parents coming over here. You yourself have lived a little bit in different parts around the country. You're originally from Texas, moved to San Francisco, lived in San Francisco for most of the rest of your life. What's something unique about your upbringing and your background that you see pop up give you extra perspective in your environmental work today?

Eddie Ahn: In Texas, it was a very suburban lifestyle that I grew up in, driving to wherever you wanted to go, whether it was school, the grocery store, et cetera. Then right after, I got to experience New England by going to college at Brown. That itself was a very different setting to live in. It was much more close-knit. The communities were up against each other. For me to go to San Francisco, it felt like a natural evolution where, geographically, it's a relatively small city, 7x7 miles with a lot of people crammed in there. To experience diversity in that context was really eye-opening for me.

I've always thought environmental justice itself should come from a sense of place like understanding where you live, the communities that have been there for a long time, and then, of course, humbling yourself, being able to respect those histories. A lot of my nonprofit's work occurs even outside its physical office address, so working with whether it's across different neighborhoods, up and down the state even like areas as far away as a five, six-hour drive from San Francisco. That act of going to the community, being willing to embed yourself in that community for days or even weeks at a time, is a really important part of the work. Because if you don't understand the geography of where you live in the communities, it's very hard to do the policy work effectively.

Kousha Navidar: Talking about that, how did you witness issues as a result of climate change impacting residents in San Francisco day to day?

Eddie Ahn: I think on a hyperlocal level in San Francisco, you've seen it from things like wildfire smoke wafting over from the earlier Northern California wildfires in 2020, again, when that sky was turning bright orange in a way that people did not anticipate. Of course, we've seen that repeat itself--

Kousha Navidar: Oh, I think we might have Eddie frozen here. We might have to try it again.

Eddie Ahn: Did you lose me for a minute?

Kousha Navidar: Oh, Eddie, you're back on. No worries. We got you right here. You might want to turn your camera off maybe just to preserve the bandwidth, but I think we got you back. Do we? Folks, this is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Kousha Navidar. We're talking with Eddie Ahn, who I believe is right back on here. Let me just reintroduce it. We've got him who is an environmental justice attorney and nonprofit worker. His memoir is called Advocate: A Graphic Memoir of Family, Community, and the Fight for Environmental Justice. Eddie, a little technical hiccup there. Can you hear us now? Are you back with us?

Eddie Ahn: Yes, I can.

Kousha Navidar: Wonderful.

Eddie Ahn: Thanks for your patience.

Kousha Navidar: Oh, not at all. The last thing that you were talking about is how climate change shows up. You were talking about the wildfires in 2020. I think you were moving on from there.

Eddie Ahn: Then even with sea level rise, which was more traditionally how climate change was understood 15, 20 years ago, we're starting to see the effects of that now in the Bay Area, which is a third of California's coastline, but also estimate to essentially sustain over two-thirds of the economic damage involved with rising sea levels across the California coastline. In other words, it's literally going to be $100 billion-plus worth of damage to infrastructure. Everything from buildings to highways to ports, it's going to wreak havoc in people's lives in a way they currently do not see. It's all resources that need to be mobilized and preparation that needs to happen now.

Kousha Navidar: I think it is such an important beat in this conversation to bring it back to Earth Day because I'm sure folks listening will say, "Of course, these are issues impending tragedies that we think about or are told about in the media every single day." Today on Earth Day, I'm wondering for you, Eddie, as someone who's so steeped in this work, do you ever have mixed feelings on days like this? Because we're trying to celebrate environmental protection, but there's so much to be concerned about. How does that sit with you?

Eddie Ahn: I am worried. As a good environmental advocate, I would always want every day to be Earth Day, but I also recognize the importance of highlighting the visibility of environmental action on at least a single day of a year. I do think the realities of climate change, the impacts that are happening will also force us to realize not just recognizing it one day of the year. Mixed feelings overall, but glad that this is still happening.

Kousha Navidar: I think that your policy work that you say is at a high level, but your experience in advocacy really starts at the grassroots. You're a great person to get perspective on an element of climate advocacy that I always find particularly challenging because we're always told about the things that we as individuals can do, recycling, changing our eating habits generally, decreasing carbon footprint.

Obviously, there's this whole other narrative about who's actually able to move the needle, talking about corporations, et cetera. I just saw this statistic from the advocacy group CDP, which is the Carbon Disclosure Project, saying that just 100 companies were responsible for 70% of greenhouse gas emissions over the last two decades. I guess to sum it all up, when people ask you what they can do and if it makes a difference, how do you make sense of it? What do you say to those folks?

Eddie Ahn: I think it does make a difference. I do think there, nowadays, is a growing argument around, "Individual carbon footprints don't matter," which I do not believe in. I do think individual carbon footprints do matter, but I also hear the argument for system-level change. The scale and speed in which climate change is happening means that, collectively, we have to do bigger and greater actions to try to address them. I don't think it means total apathy at the end of the day.

If you are overwhelmed or anxious about climate change happening, it doesn't mean you just throw up your hands and just let the governments take care of it because part of it does require that interplay of understanding what is my individual responsibility in all this, but also hopefully supporting overall whether it's regulation or resources being mobilized. It does take a lot to address climate change, so the overall system-level actions will help us get there.

Kousha Navidar: Is there anything about the state of climate policy and advocacy that's giving you life right now, that's giving you hope, that makes you optimistic?

Eddie Ahn: Personally, I do like technological innovations that have come from trying to address climate change. One of the technologies that my nonprofit has worked in for some time now is offshore wind, which is wind turbine farms being set up currently across the northeastern seaboard and being proposed right now for the West Coast, particularly in California. I do want to caution that offshore wind is not some kind of magic bullet to climate change.

It's not the end-all-be-all solution, but that we can create what are essentially fantastical machines. These machines are the size of the Eiffel Tower. They can potentially either float on water or be fixed in mass in hundreds of turbines also shows me a lot about human ingenuity and a willingness to try to address these problems. Seeing technologies like that rise to the forefront makes me optimistic that we can create solutions.

The other balancing act in all this is also saying tech is not itself the solution to climate change. It requires working with communities well. A lot of, again, my work at Brightline Defense is about trying to implement equitable solutions around something like offshore wind. Making sure we work hand in hand with local communities on the ground is an important part of solution-making.

Kousha Navidar: If you're just joining us, we're talking with Eddie Ahn, who's an environmental justice attorney, nonprofit worker, and artist. Just published a new graphic memoir. It's titled Advocate: A Graphic Memoir of Family, Community, and the Fight for Environmental Justice. It's out right now. I want to dive into the book a little bit more, Eddie, because it is about environmental advocacy. It is also very much about just being a part of a community and understanding what leadership looks like.

One of my favorite elements of this book was when you illustrate the scene of a funeral for community advocate Dr. Espanola Jackson. There are so many details included from the arches to the crosses and the shadows cast down from the pews and the color of these drawings that are bluish. It just gave this sense of who Dr. Jackson was as a person and the impact that they had on the community. I'm just wondering, could you say a little bit about who Dr. Jackson was to you and what legacy she left behind?

Eddie Ahn: I'm glad you mentioned the art specifically of the book and particularly of those scenes because the book is intentionally told through a series of color shades. These color shades signify different eras, periods in my life. They're supposed to also signal shifts between time and mood as well. The color used to describe Dr. Espanola Jackson is in purple. It was Dr. Jackson's own personal favorite color.

I think a lot about that period as a transitional stage period in my life too, where if you think about the creation of purple itself as a color between the mix of blue and red, it was very much about finding my own way to advocacy. I am very grateful for Dr. Jackson, who was a very strong Black woman community leader from Bayview-Hunters Point who understood the value of fighting for her community. She came up in the LBJ area of federal aid and assistance and the war on poverty and understood the need to fight for what was theirs and the battle of resources that often is in urban history.

I think Dr. Jackson also, to her credit, was very good at coalition-building and building ties across different community activists. Even as she aged, she was incredible with me personally in sharing her knowledge about the decades of activism that she had engaged in and was even willing to welcome someone like myself into our own home and have these long chats. That's not something nowadays in the post-pandemic era, I'm sure, people would naturally do. I think a lot about those days. The way she always framed it to me was about making sure you not only pick up the sword yourself but also find other people to take up the sword with you as well in the future.

Kousha Navidar: How do you see that playing into the work that you do today and the ways that you maybe suggest other people get involved even if you don't work for a nonprofit being a part of the solution rather than the problem?

Eddie Ahn: If people want to get involved, I recognize the nonprofit sector is not for everyone. It doesn't pay nearly as well as other sectors. It will always take more from the individual than what that individual will give to the communities involved. It's very much a charitable act in my mind at the end of the day. If people do go on and whether volunteer at a service-oriented nonprofit or even work at a policy-oriented nonprofit, I would just search two things.

One, to try to do it consistently beyond just, say, a single day of action. Maybe thinking along the lines of, "What can I do week-to-week or a month-to-month that is more consistent in that action?" Also, just to be humble about it as well, to not presume that one knows everything. I do think that's helped a lot in my work just to be able to understand in a lot of situations that I walk into. I don't know everything and that I'm willing just to sit and listen as I did with Dr. Jackson in Bayview-Hunters Point.

Kousha Navidar: Before we wrap up, I just want to point out another element of the book that I loved, which is burritos. A big part of your book is about burritos. At one point, you write that you used to measure time in burritos because you ate so many. I was lucky to live in San Francisco for some time. I spent my fair share of it eating burritos. As I read that in the book, I just knew I had to ask this. All things considered, where's the best burrito in SF?

Eddie Ahn: Oh goodness. Burritos, by the way, for listeners who may not be aware in the Bay Area, are very distinct from, say, burritos in Texas, which I also ate while growing up. Burritos in the Bay Area have a ton of stuff jammed into it like guacamole, cheese, beans, et cetera, rice as well. It's a whole feast unto itself. Taqueria Cancun is one place I really enjoy. They have three locations in San Francisco. I can actually make distinctions on how each burrito tastes between those three locations. The one on Mission Street and close to 19th Street is my personal favorite.

Kousha Navidar: I used to work right next to Taqueria Cancun actually. Yes, I will also attest to that. Very good. Eddie Ahn is an environmental justice lawyer and activist. His new book, graphic memoir is titled Advocate: A Graphic Memoir of Family, Community, and the Fight for Environmental Justice. It's out right now. Eddie, thank you so much for your work and for joining us.

Eddie Ahn: Yes, thanks again for having me, Kousha.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.