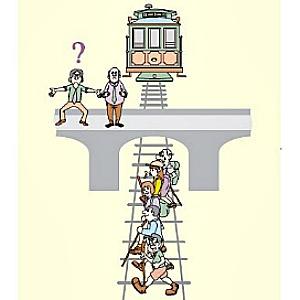

BROOKE: If words matter, then it naturally follows that the language matters, too. Especially when it comes to solving a moral dilemma. That’s according to a study published in April called “Your Morals Depend on Language, ” authored by University of Chicago psychology professor Boaz Keysar and Albert Costa, a psychologist at Barcelona’s Pompeu Fabra University. When we spoke to them last spring, the told us that our decisions can change radically depending on whether you reach them in your native tongue, or in a second, learned language. In his research, Boaz used a classic social science hypothetical: imagine you are standing on a footbridge. An out-of-control trolley passes underneath, hurtling toward 5 people who will die, unless you stop the trolley by dropping a heavy weight in front of it. A very large man stands beside you. Do you sacrifice him to save the other 5?

PROF. BOAZ KEYSAR: Right, so we did not invent that. A lot of research shows that most people don't want to push the man.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Only about 10 or 15% of people would actually throw the man out, in order to save the five others?

PROF. BOAZ KEYSAR: Exactly. That’s been documented in dozens, if not more, of experiments. They viscerally cannot do it. They have a very strong reaction to the idea that they can push someone to their death, even though they can make the calculation, you know, basically, they’ll save five people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And that’s when you're asking people in their native language.

PROF. BOAZ KEYSAR: Exactly.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But when you ask people in a foreign language, one that they understand but isn't their natural tongue, things change radically.

PROF. BOAZ KEYSAR: And that’s exactly what we predicted. When you are thinking about it in a foreign language, it gives you a psychological and emotional distance from the problem. And then more than 40% of people then are willing to say, “Yes, I will do that.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, Albert, while Boaz was doing this in Chicago, you were doing an almost identical study in Barcelona, totally by coincidence.

PROF. ALBERT COSTA: Right, right. We didn’t know each other at that time, and then one day I call Boaz and I said, look, we have these weird results. And then before I finished the sentence, Boaz said, well, I know what you have.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

How do you know? So what you have is that people push more the large man off the bridge in a second language, in a foreign language. I said, yes, that’s right. So we joined forces and we had different samples and it’s a very strong, experimentally speaking, a very strong report.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, it’s my understanding that a truly bilingual person would have the same kind of emotional resonance in both languages. Is that true?

PROF. ALBERT COSTA: Right. People that have learned the second language in the context of social relationships, these people are going to use the second language, emotionally speaking, in the same way as the first language, okay? I mean, this – in our sample in Barcelona, many of the people knew two languages - Spanish and Catalan. And when we split them according to the first language, that being Spanish or Catalan their were no differences in the amount of people that decided to push the man. Whether you were Spanish as a first language or Spanish as a second language but having learned that second language very early on in life, didn’t make a difference. PROF. BOAZ KEYSAR: I’m not a native English speaker, and I have the sense that I make decisions differently when I use English than Hebrew. When you use a foreign language, you have a different reaction to the words, especially emotionally-laden words. You don't get the same emotional resonance. A lot of moral dilemmas, the decision involves an emotional reaction, so we figured reducing the emotional reaction by using a foreign language might lead to a different decision, a different choice.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But can you prove that? Or is it simply that they’re working harder to understand the problem in the non-native language, and since they're taking extra time and, and don't respond reflexively, maybe that leads to more logical thinking.

PROF. ALBERT COSTA: In our previous study, we ran an experiment in which we asked participants to solve some logical problems that did not involve any emotional component. So you have a baseball and a baseball bat that together cost $1.10. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You say 70% of the people, among whom I am, [LAUGHS] would assume that the ball costs 10 cents, but it’s wrong.

PROF. ALBERT COSTA: People respond “10” because it’s an intuitive response that comes to mind quickly, right, so it’s obvious that it’s 10. But it is not. Now, when we present this problem in a foreign language, people didn’t respond better to those problems. Now, if it’s only a matter of working harder, the fact that we didn’t find the effect there will suggest that, to some extent, emotion is involved in driving this effect.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Boaz, you also looked into the effect that thinking in a foreign language has on risk taking, and you found out people are more likely to gamble in a foreign language. Why would people take risks, if they were thinking more logically? What am I missing here?

PROF. BOAZ KEYSAR: We actually looked at risks that are worth taking.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Oh, those!

PROF. BOAZ KEYSAR: You know, we take risks all the time. So how about I offer you $100 in your hand, or we’ll flip a coin and I’ll give you $10,000 if it’s heads or nothing if it’s tails. Would you take the risk?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The logical thing would be for me to take the 50-50 chance that I could get $10,000.

PROF. BOAZ KEYSAR: Yeah, assuming that $100 is not gonna make you or break you, then yeah, you will take it. So we gave people $20 and we said, we’re going to play a game now, for real, 20 rounds. Each round, you take a dollar and you either put it in your pocket or we’ll flip a coin and if it’s heads, we’ll give you $2.50, if it’s tail you get nothing. And you do it 20 times.

If you’re an economist, you would take all the bets. On average, you’ll come out ahead. But people don’t like to do this. People hedge their bets. So people take about 50% of these bets.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But in a foreign language, they took more.

PROF. BOAZ KEYSAR: They took about 70% of the bets. They operate with a little less fear of losing the dollar. In a way, they’re less inhibited by their fears.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So Albert, what do you think? Should we always think about difficult problems in a foreign language?

PROF. ALBERT COSTA: Well, sometimes to take a decision driven by emotion is important. We don’t want to appear and like say that the logical options are always the good ones. I mean, sometimes you have to go with your gut feeling, and that’s correct. So this depends on the problem. Now, for say, financial problems that companies may have, it would be good to have a group discuss the issues in a foreign language and the other group discuss the issues in a native language and see whether they reach the same decisions. In those situations, speaking in a foreign language would help to make decisions more accurately.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Is there anything in your own life that you wish that you had considered in your second language, rather than your first?

[PROF. KEYSAR LAUGHS]

PROF. ALBERT COSTA: Yeah, fights. You start having a fight with someone and you start speaking a second language and the fight is heating up, pretty often you switch to your first language and you say things you don't want to say. So when you fight in a second language perhaps you can have more psychological distance and you can cool and perhaps you can have some psychological distance that allows you not to say things that you will regret later on.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

PROF. BOAZ KEYSAR: Right, so this is my life. I live in English but my native tongue is Hebrew. And my wife and I are celebrating our 25th anniversary this August, and maybe we are able to do this partly because in our fights, it’s much easier for me to say, “You’re right.”

[PROF. COSTA and BROOKE LAUGH]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In English.

PROF. BOAZ KEYSAR: Because it’s in English, exactly.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] Boaz Keysar is a psychology professor at the University of Chicago. Albert Costa is a psychologist at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. Thank you so much.

PROFESSORS COSTA AND KEYSAR: Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: They are both authors of the study, “Your Moral Depends on Language.”