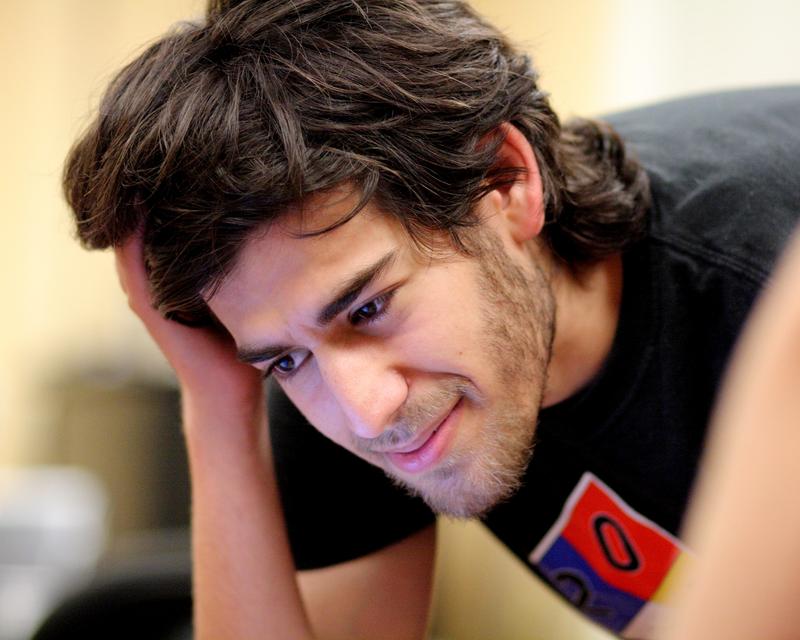

The Wunderkind of the Free Culture Movement

( Sage Ross/flickr )

BOB: This is On the Media, I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. When we left off with Justin Peters, Noah Webster’s copyright campaign had paved the way for laws that would protect the creators of information -- literature, music, film -- with robust copyright terms. The idea that the nation needed a public domain rich with free, and freely available information was receding. But the advent of the internet created an opportunity for some fervent free-culture advocates to step in. In the late seventies, for instance, we encounter Michael Hart, Swartz’s spiritual progenitor. Peters suggests that people like Swartz, like Hart, people passionate about information, share certain traits.

PETERS: I think these data moralists, to use a term I may or may not have coined...they live lives free from ambiguity. of the rightness of their causes. How either expanding or restricting access to information is not just good for readers and writers but for the country as a whole. And Michael Hart is definitely in that line, he's a critical sort of bridge figure between the old guard publishing world and the burgeoning world of the internet.

BROOKE: Yeah, you call him the beginning of the story of the free culture movement.

PETERS: Yeah, Michael Hart created the first eBook. It was on July 4th 1971, he was doing a sleepover in this computer lab at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. And he had this sort of flash of inspiration that people have - I've never had one, but - one of these days. He had this flash of inspiration - he announces to the people sitting beside him, sidebar: Michael Hart seems to have spent a good portion of his life announcing things to people who might not have cared to hear it, right? He announced that the greatest value created by computers would not be computing, but the storage retrieval and searching of what was stored in our libraries.

BROOKE: Yeah, I mean, think about when he said that - this was when computers were still for crunching numbers.

PETERS: Yeah, they were basically all used for mathematical and scientific purposes. And here's this guy, this guy who had dropped out of college twice, who had been in the army, had left early, had spent years hitchhiking across the country, and trying to make it as a folksinger, who finally has this flash of inspiration when he's in his early 20s that he's like, okay, this is what I'm going to do with the rest of my life. I'm going to devote my life to typing up public domain texts and storing them in computers for the benefit of humanity, and that's exactly what he did.

BROOKE: He created what may be familiar to many listeners, something called Project Gutenberg.

PETERS: Yeah, Project Gutenberg was the first general interest online library. He spent the first sort of 20 years of his project toiling in obscurity, sort of bouncing from job to job during the day, he spent the entire 1980s transcribing the King James Bible. It's very long book.

BROOKE: And he was basically camping out at a university computer.

PETERS: Yeah. Exactly

BROOKE: And they just let him basically couch surf?

PETERS: Because like no one else really knew what they were for. And then the world wide web comes along and people start discovering this project and then they start typing up public domain texts that they find and sending them to Hart, and then gradually this becomes an actual online library. So in the 1990s when the commercial potential of the world wide web finally becomes apparent to people, Michael Hart had put 250 e-texts online, which might not sound like a lot, but if you think about the amount of labor required to sit and literally transcribe an entire book on early software programs, then you get some sort of a sense of the hugeness of this accomplishment.

BROOKE: And he gets kicked off that computer.

PETERS: Yeah. By that point right around the 20th anniversary of Project Gutenberg, the University of Illinois and indeed the rest of the world are starting to learn what computers are for, and what the're not for, right? And they're beginning to realize well they're not for people like Hart. And so they revoke his access and the project maintains, I mean he finds a new home for it, but the fact that this happened, right when you know by all rights the world should be looking at this great beautiful thing, and saying "more please! how can we help?" just sort of illuminates the initial dichotomy that we were discussing earlier of information wants to be free, information wants to be expensive, and there's this endless tension between the two.

BROOKE: So, Aaron Swartz. Swartz is growing up a precocious kdi in the suburbs of Chicago, at which time he creates a kind of precursor to Wikipedia and then at 14 he helps develop RSS, which helps people syndicate information online. And then he meets Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig when he's 15, and he gets himself involved with Lessig's effort to create a way to provide information for free under certain circumstances.

PETERS: It was a project called Creative Commons. An attempt to create a middle ground for copyright in the digital era, where you could go on to creative commons and register your content with Creative Commons license, which was basically just a signpost you'd put up to say "okay, if you are using this for example for a non profit, purposes just give me credit' or you could say 'look, anybody can use this photograph or this song or this short story'. It was basically an attempt to say look, our copyright law at this point needs to adapt to the realities of the digital age, but if it's not going to adapt on its own, then we'll find a workaround.

BROOKE: As we follow Swartz, he drops out of high school, he then applies to Stanford, gets in, drops out of there, he's involved with the founding of Reddit. And somewhere along the line, you write about Swartz reading Noam Chomsky's book Understanding Power.

PETERS: On his blog, he wrote that after he wrote Understanding Power, he was literally struck down to the floor. I think he said something like "I couldn't stand up, I couldn't think straight, I had to grasp the doorknob to keep myself upright." Anyway, after reading that book, something seems to have switched and he seems to have realized now that I've seen this, I can't unsee it. Now that I've seen how power works and accumulates, I can't pretend that I don't know how the world works.

BROOKE: I mean we're still talking about a kid here.

PETERS: Oh yeah, I mean, he was 14. He was 14 or 15 when he started working with Creative Commons. By the time he's writing about Chomsky he's barely 20 years old. going across the country speaking to groups about the moral necessity of liberating pieces of culture and information that are held as literary property.

BROOKE: And in fact, he embraces revolution.

PETERS: Of a kind, yea.

BROOKE: He drafts the Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto. He starts the content liberation front. I mean, these are phrases at least designed to evoke revolution. And I have a quote here the Guerrilla Open Access manifesto: "It's time to come into the light and in the grand tradition of civil disobedience declare our opposition to this private theft of public culture. We need to take information wherever it is stored, make our copies and share them with the world. We need to buy secret databases and put them on the web. We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks. We need to fight for guerrilla open access. With enough of us, around the world, we will not just send a strong message opposing the privatization of knowledge, we'll make it a thing of the past. Will you join us?"

PETERS: And then two and a half years later he's arrested at MIT after having downloaded 4.8 million academic journal articles. He never admitted or said he was planning to do with all of the material he had acquired. You know the federal government certainly took the Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto to heart, and they said, look, he wrote about taking thse gigantic data sets and freeing them to the world, then he downloaded all f this material, so it was clear to them at least what they thought that he wanted to do with it.

BROOKE: So, tell me how the - how the case unfurled.

PETERS: Yeah, so, it's the beginning of January 2011 when he's first arrested and at first, they bring him up on you know, state breaking and entering charges --

BROOKE: Cause he did it from MIT.

PETERS: He did it from MIT where he was not enrolled and he wasn't sort of employed there. But then federal prosecutors get involved. This joint computer crime task force that was working the case with MIT cops, Cambridge cops, and the Secret Service.

BROOKE: Now basically JSTOR, this repository of academic journals that you have to subscribe to, probably wouldn't have cared except that he was doing it on such a massive scale that it slowed down and crashed their servers initially.

PETERS: Yeah. He was making hundreds of download requests per second, and there was a big strain on the JSTOR servers, and the JSTOR staff looks at this activity and thinks, whoa, someone is trying to siphon our entire archives so, they start telling MIT hey you gotta find the guy who did this. And when the found him, and they found out that it was Aaron, not some malicious hacker, but a guy who had in many ways established himself as if not the conscience of the internet a least one of them. No one really knew what to do with him.

BROOKE: Except the prosecutors.

PETERS: Oh they knew exactly what to do with him. They wanted to put him in jail. And they would not budge from that stance, and they charged Aaron under something called the computer fraud and abuse act, the CFAA, which is America's sort of omnibus computer crimes legislation that serves to prosecute malicious hackers who are trying to tap into government computers to find state secrets. It can also be used to prosecute you or I if we sort of violate a website sort of terms or service. I mean it's an incredibly broad piece of legislation. And so Swartz returned all the documents he had taken, he gave them back to JSTOR. And then JSTOR called the prosecutors and said look, we've got what we wanted, we have no interest in seeing him go to jail, we have no interest in seeing this case proceed, and the prosecutors said, thank you very much, duly noted, and then they delivered an indictment that could have theoretically landed him 35 years in a federal prison. And then they delivered a superseding indictment that upped that to a potential 90 years. He never would have received the maximum sentence, that was just there for scare value. But still, the lead prosecutor in the case made clear that if they went to trial, and if Swartz lost, the prosecutor would ask that he be sentenced to around 7 years in federal prison.

BROOKE: The boy and the man you describe, Aaron Swartz, couldn't handle any confinement, he couldn't make it through high school, he couldn't make it through college, he couldn't even work at a cozy comfy job at Reddit.

PETERS: He was a very sensitive kid who couldn't stand having to play by someone else's rules. By which I mean,you know, he was a product of the Internet, where the collaborative digital world in which you advance by sort of the strength of your own ideas and your contributions to the group, right? And if there was a better way of doing something, a better way of solving a problem, then everyone said, great, you found a new way, let's do that. That dynamic just is very hard to find in the real world. You can't go to high school and say, all right, we've got this four year structure here, I've got this better way that is better suited for me. He tried to do that. They said, duly noted, no. So he left. He was in the first class of Y combinator start ups - Y combinator is the big start up incubator that's relatively famous - he couldn't take that. He did not like being forced to work on one thing that was not his thing.

BROOKE: If it didn't have the potential to change the world, he lost interest. One of his friends said that he always felt like they were disappointing Aaron. That they couldn't live up to his standards.

PETERS: Well you know he was the sort of person who was a great friend but could be a difficult collaborator because his mind was working on a different frequency than everyone else. And I think that was partially why he ended up starting so many projects and then leaving them, because they couldn't live up to his own standards.

BROOKE: So how did he die?

PETERS: It was January 2013. It was becoming more and more clear that this case wasn't going to go away. He gotten lawyers, they were very good lawyers, and they were going to try to convince a judge to exclude a bunch of evidence that the government was planning to use. That's the thing that kills me that I just dont' understand after living with this story for so long. It felt like things were looking up for him, right after living under the strain of an extended indictment for 2 years at that point. The case was looking like it might resolve in his favor. And he had a girlfriend whom he loved, and their relationship had never been stronger. And everything seemed to be going so well. And then one day his girlfriend comes home from work to find him hanging by his own belt. And the entire world sat up and asked why.

BROOKE: There have been basically two competing narratives about Aaron Swartz since he died. One is that he was a restless frustrated young man, a high school college dropout, a social misfit, a difficult colleague, and then there's the narrative that asserts he was smarter than all of us, possessed with more commitment and integrity and generally just too good for this world, and actually those narratives don't preclude each other. Both could be true.

PETERS: He's an idealist. Someone who has a very clear idea about how the world should be and about what he can do to bring the world to that point. And yet, he was ill equipped to deal with how the world actually was.

BROOKE: Did your opinion of him change as you reported the story?

PETERS: It did. Honestly at first I came at this story on sort of the side of stringent copyright, I'm a journalist I've seen a lot of my friends lose their jobs in this last decade because no one's paying for content anymore. And the more I learned about this story, the more I'm like this is an extraordinary guy. You know what he was? He was a herald. This is near the end of my book where I sort of try to sum it all up. It's three years on, the story of his life and death serves as a necessary reminder that there is a fundamental disconnect between our laws and our habits. Between the way we are supposed to conduct ourselves online, and the way we actually do. We can amend bad laws, we can promote better culture, we can choose to create systems that can be opened without breaking. Tolerate deviants without collapsing. Regard the unfamiliar not as a threat, but as an opportunity. Who Aaron Swartz is to me, he's the living manifestation of those ideas and those ideas are supremely important today, tomorrow, in the future, as information continues this paradoxical need to be free and expensive, what it ends up as, it's up to us.

BROOKE: Justin thank you very much.

PETERS: It's such a pleasure, Brooke.

BROOKE: Justin Peters is author of the new book The Idealist: Aaron Swartz and the Rise of Free Culture on the Internet.

BOB: That’s it for this week’s show. On The Media is produced by Kimmie Regler, Meara Sharma, Alana Casanova-Burgess, Jesse Brenneman and Mythili Rao. We had more help from Alex Friedland, Dasha Lisitsina and David Conrad. And our show was edited by…Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Cayce Means.

BROOKE: Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s Vice President for news. Bassist/composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB: And I’m Bob Garfield.