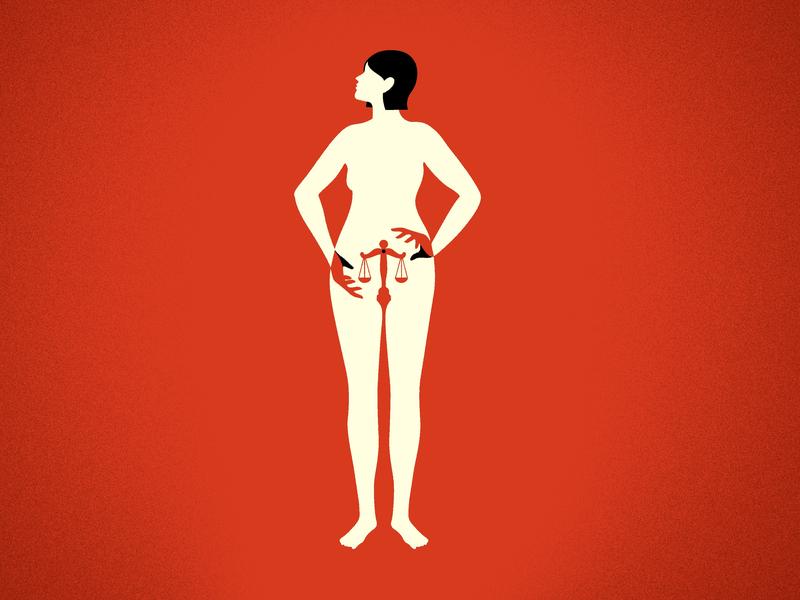

Will the Supreme Court Overturn Roe v. Wade?

[music]

Jia Tolentino: As we know, the Supreme Court is wrestling with two state laws with possible repercussions for abortion access all across the country. On the one hand, there is Texas' SB8 which is already in effect while the judges are deciding whether or not it's constitutional, and in a couple of weeks, the court hears oral arguments in the Mississippi case. That one is known as Dobbs v Jackson Women's Health Organisation.

David Remnick: There are a lot of issues here we need to unpack. Happily, we're joined by Jeannie Suk Gersen. Jeannie is our colleague at The New Yorker, a constitutional scholar, and a professor of law at Harvard. Jeannie, in recent months, Texas and Mississippi have taken very concrete legislative steps to ban abortion. Private citizens in the federal government have sued as a result, and soon the Supreme Court is going to be reviewing all of these actions, so please, help us get up to speed on these cases and their chances in the Supreme Court.

Jeannie Suk Gersen: In the Mississippi case that will be heard in early December, Mississippi is explicitly asking the Supreme Court to overturn Roe versus Wade. Mississippi passed a law that clearly contradicts Roe versus Wade, and that law essentially says that you cannot get an abortion after the 15th week of pregnancy. That contradicts Roe versus Wade because Roe versus Wade and then the subsequent case that clarified it Planned Parenthood versus Casey made clear that until the point of viability, a person does have a right to an abortion and viability at this point is thought to be 23 to 24 weeks.

15 weeks versus 24 weeks, that's the gap where it contradicts the Supreme Court's abortion precedence. The Texas law is even more in violation of Roe versus Wade in that it tries to prohibit abortion after the sixth week of pregnancy. The thing about the Texas law that is different from the Mississippi law and different from other abortion restrictive statutes is that normally when you want to challenge a law as unconstitutional, what you do is go into court and say the state has passed this unconstitutional law and deputize a state official to enforce it.

Here, it specifically says that state officials cannot enforce this law only private citizens, so the only way that an abortion provider can challenge a law like SB8 is to wait until they are sued by a private citizen under SB8. That means that they will be chilled from actually performing abortions and that essentially creates a reality in which abortion rights are very severely restricted, if not eliminated in the State of Texas.

David Remnick: What made certain players in Mississippi and Texas think that they could somehow bypass, override, or plow through Roe versus Wade in the Supreme Court?

Jeannie Suk Gersen: Ever since the Casey decision, states have been trying to do what they can within the bounds of the Supreme Court's abortion jurisprudence to try to limit abortions in whatever ways that they think are permissible. In the recent past, we've moved into a new era, wherein people are trying, states are trying to actually pass laws that they know are unconstitutional under the Supreme Court's cases and they're doing so precisely because of the change in personnel on the Supreme Court because they can count the votes and they can see that there will be a majority of justices who probably disagree with Roe verse Wade and might be willing to overturn it.

David Remnick: The Supreme Court in its majority now is anti-abortion, I think it's fair to say, but do you see evidence that the judges may be offended by this strategy in a legal sense, and that they may rule against them?

Jeannie Suk Gersen: David, is your question about whether justices are offended? They certainly ought to be. The last time we had a significant challenge, and I'm not exaggerating to say this is as significant, to federal judicial power was after Brown versus Board of Education, which was also about a constitutional right, of course. We had states in the south saying we don't want to obey Brown versus Board of Education, and we have our own interpretation of what the Constitution requires, and the Supreme Court said, "No, we are the arbiters of what the Constitution says, we decide what the Constitution says, not you the states."

The Supreme Court is now faced with, not only the issue of abortion, which it will directly address in the Dobbs' case but in the Texas, the whole woman's health case, they are actually deciding a question that is completely, in some ways, divorceable from abortion altogether. It's about their own authority as a Supreme Court. Who is supreme here? Is the federal government supreme here or are the states? Who are supreme here?

Jia Tolentino: As a Texan and as someone who loves my state in many ways, it is a profoundly Texan ideology and strategy. This is a state where the state flag flies more than the American flag often. I just remember I was talking to a bunch of people in Texas around when SB8 was allowed to go into effect, and they were reminding me that every single year at the state legislature, it's dozens of bills, anti-abortion bills that are trying many different strategies. It's anti-abortion spaghetti being thrown against the wall, and this one happened, the strange, strange law happened to stick.

Jeannie Suk Gersen: I like the expression of anti-abortion spaghetti being thrown against the wall, but this particular spaghetti they knew had a good chance of having some more sticking power because of the change in composition of the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court, I have to say, they have to be disturbed by that or they ought to be because do they really want to look like a body that essentially can be manipulated in this way, that essentially the law that you will basically try to get around constitutional rights because so and so got appointed instead of another person?

Essentially, it comes down to who got elected president before that. It would be very mystifying to me to have the Supreme Court actually in the Mississippi case, say, Roe versus Wade is overruled. There are, of course, many things that can do short of overruling that can be quite devastating, but I am not expecting to read ruling months from now where they say, "We hereby declare that Roe versus Wade is no longer good law."

David Remnick: You don't think they'll overturn it?

Jeannie Suk Gersen: No, I don't think that we're going to see an outright overturning of Roe versus Wade, I think we're going to see something more along the lines of Casey in 1992, and that move is just to say, "We're not overturning, but here we're clarifying." They're probably going to do something that clarifies the meaning of undue burden, which is language that was first expressed in Casey and to try to clarify what undue burden means in a way that makes abortion harder to obtain, but overturning Roe altogether, it just would be so embarrassing to the court, so bad for its legitimacy.

Just think about the year we've had. This is 2021, we're in a year, first of all, where we started the year with a violent attack on the Capitol, on our lawmakers, and everyone knows that the situation is such that Roe versus Wade represents, not only the right to an abortion, but in some ways, it's so much larger than that. Roe versus Wade represents the legitimacy of the court and the court's decisions. On the right, Roe versus Wade represents how the court isn't legitimate because it did something. Essentially made up a constitutional right that's not even in the Constitution.

On the other side, Roe versus Wade represents the legitimacy of the court because, despite its unpopularity among some quarters of society, the court has stuck with it and affirmed it again and again and again under the principle of stare decisis, which is the principle that cases that are decided are supposed to stand because if you keep changing the ruling every year, then how is that even law?

David Remnick: We're talking with Jeannie Suk Gersen about the challenges to abortion rights now being heard by the Supreme Court.

Jia Tolentino: Can I ask a question? You spoke about abortion being an invented right in the Constitution. In an alternate universe, what is a kind of case law that would establish an affirmative positive right to abortion? What might that look like.

Jeannie Suk Gersen: What was interesting about Roe versus Wade is just the way that it is so connected to other kinds of personal rights. It didn't just come out of nowhere contrary to what some people may say about it. It was the Supreme Court built this doctrine one step at a time and really it goes back to the notion that there are certain things that are so fundamental to what it means to be a human being that no government can take that from you.

Jia Tolentino: Right, it's privacy.

Jeannie Suk Gersen: Right, and so privacy became a concept that housed the collection of things that human beings consider essential to concepts like dignity and self-determination. The way that the Supreme Court first approached this was in the context of contraception, the use of contraception that married couples would be able to enjoy in the privacy of their own home. The Supreme Court faced with that, I think, was offended at the idea that the state would get to say whether a man and wife would use contraception or not in their own private sex life in their bedroom.

That was really the imagery and the rhetoric and just like, "Get big brother out of here" kind of idea that led the Supreme Court to say due process protects that right of essentially privacy. The privacy of the bedroom, the marital home, that that was very essential. Of course, once you have that, then you can extend it to the right of everyone to use contraceptives without the state telling you whether to do it or not, whether you're married or not. Then that leads to the contraception being a reproductive decision.

That's then what provides a bridge to abortion decisions that you don't want to get pregnant, you should get to choose if you get pregnant or not, and you should get to choose whether you have a baby or not. It's one step at a time. It's not like completely invented out of whole cloth. Then, of course, we know that out of abortion comes the right to have the state not be able to tell you that you can't have sex with the same-sex partner. In 2003, out of those cases, we get the ruling that the state can't criminalize same-sex sexual conduct because that's also part of the privacy, particularly in the home, in the bedroom.

Then out of that comes gay marriage, same-sex marriage. This is like an entire web built step by step one case at a time. Now people can say, "Maybe abortion rights wouldn't be so threatened right now if we had had an alternative, a road that could have been taken instead of this one." Some people have said that. In fact, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg several times suggested that due process and privacy were not really the best way to protect a woman's right to an abortion. Then, in fact, it would have been better if basically the Equal Protection Clause would have been used instead.

There it would be because women have the right to equality and the government should not discriminate on the basis of sex. Given the central importance of reproductive choices to a woman's life and destiny, it would be important for the state to respect that choice because, otherwise, it would be discrimination on the basis of sex. Now, that's an argument that could have been pursued. Many people did think that that was a very promising argument, but once you've got the Supreme Court on board with the privacy doctrine and the contraception, you've got the path dependence, and that's how abortion doctrine went.

David Remnick: What happens if the laws in Texas and Mississippi are upheld? Does the whole house of cards, the whole legal structure that has been supporting the right to privacy, does it all collapse suddenly?

Jeannie Suk Gersen: The Supreme Court would have to do some very fancy footwork for that not to be the case. Perhaps they could do so simply by maybe like a surgical move that would say, well, we basically approved the right to abortion, but we think the details of the test that were laid out in case C were wrong. They could do it that way without touching necessarily everything else around it, but it is very unlikely that a Supreme Court that wants to go that far as to uphold these laws would do it in such a limited way because it just would look really silly.

If you're a true believer as a Supreme Court justice, you're thinking that the greatest wrong that the Supreme Court has ever done possibly, one of the greatest is to say in Roe versus Wade what it did because a lot of legal conservatives do consider Roe versus Wade one of the worst things in terms of jurisprudence that has ever happened. The whole point of upholding these laws would be to say something really deep and fundamental about the methodology that the court used in Roe versus Wade. These things can be done, but again, can they do them with a straight face while preserving the sense that these are judges, not just policymakers in robes?

[music]

David Remnick: Harvard law professor, Jeannie Suk Gersen. You can read all of her writing about the Supreme Court and much more at newyorker.com.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.