BROOKE: Ethan Zuckerman is the director of MIT’s Center for Civic Media, who’s been tracking and writing about the disparity between the coverage of Paris and Baga. I was going to ask him why the volume of coverage differed so much. But then, the answer seemed so obvious. Was it really just another open and shut case of you know what?

ZUCKERMAN: Yup. Racism is part of it. Yup, it’s really, really far away. But part of it is that there are versions of terror that seem like it’s easy for us to have conversations about, and ones where it’s hard to have conversations about. Syria, in particular, because once you say, ‘It’s terrible what’s going on in Syria.’ The logical question is, "What should the U.S. do?" Do we intervene? Would that actually work? Whose forces would we back? And that’s very, very similar to the situation with Boko Haram. You sort of look at this, and you go, "I don’t like any of these alternatives." Charlie Hebdo is easy for us to have opinions about. It’s quite black and white. There’s a lot of ways to sort of hang existing beliefs and perceptions on it.

BROOKE: It was an attack on a principle that most Western nations share.

ZUCKERMAN: We can sort of look at it and say, "We must defend the free press". Or we can say, "I’m going to defend their right to speak but I’m sure not going to defend what they’re speaking about."

BROOKE: It’s a highly-connected global city. Thousands of working journalists.

ZUCKERMAN: We can imagine ourselves as being part of it. We can imagine the gunmen busting into our office. But, I really think it’s more than that, Brooke. I really think it’s a sense of...news has a start and an end to it. And people who follow Nigeria closely, the answers that they give to what you’re going to need to do to root up Boko Haram, are 20 and 30 year answers. How you take care of the terrible state of economic development. We’re notoriously bad at covering stories that unfold over years, something like climate change.

BROOKE: This is what I call narrative bias.

ZUCKERMAN: And until we have individual human stories to attach to the Baga massacre, it’s going to be very hard to overcome those narrative biases. If we think about the Charlie Hebdo coverage, a lot of what I’ve read has had to do with the editor of the newspaper, and his principled and idiosyncratic stance.The Muslim police officer who was killed while defending the offices. The Muslim shopkeeper who helped Jewish customers hide in the freezer under the supermarket. These are very human stories. And we’ve all sort of jumped onto this and tweeted 'Je Suis Charlie' or 'Je Suis Ahmed'. We don’t know who to tweet about Baga. We don’t know who the heroes are. We don’t know who sacrificed themselves to save their kids. At a certain point we know so little about a story that we can’t even figure out how to get our hooks into it.

BROOKE: What’s been the difference in coverage here in the US, between the attacks in Paris and those in Nigeria?

ZUCKERMAN: I ran the numbers on media cloud. And I looked at the top 25 mentioned media sources in the U.S. On the 7th, 8th and 9th, we saw at least a thousands sentences a day mentioning Charlie Hebdo. And then doing a search in the same period of time for Baga, I got you know more like 30 or 40 a day. So that probably ends up being five or six stories. What was interesting is that in Nigeria on the 7th, 8th and 9th, there was more media coverage of Charlie Hebdo than there was of Baga. Even in Nigerian media. And Nigerians are now talking about the Baga massacre, and they’re talking about its political implications for Goodluck Jonathan.

BROOKE: What happened on social media? Have people on Twitter rallied to address the imbalance in the mainstream press?

ZUCKERMAN: I haven’t seen it. It’s actually interesting to think about three events unfolding. Right before the attacks in Paris, we had the bombing of an NAACP office in Colorado Springs. And that received very little mainstream media coverage.

BROOKE: No one was killed, right?

ZUCKERMAN: No one was killed. And you could argue that that’s why. Although certainly for civil rights activists, the symbolism of bombing an institution devoted to racial justice was ugly. And there was a hashtag campaign asking people to cover the NAACP story. Once the Paris attack erupted, it was pretty clear that that story was going to be buried. I haven’t seen a campaign trying to get people to pay attention to Baga. In fact, this is why I stayed up Sunday night.

BROOKE: Is it a false equation to compare the coverage of Charlie Hebdo in Paris, and the death of two thousand in Baga?

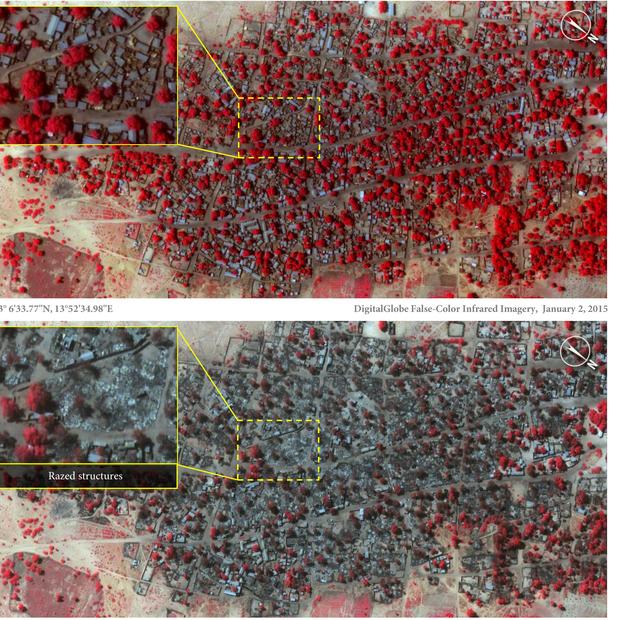

ZUCKERMAN: I do think it’s worth asking whether those are comparable events that demand comparable attention. If you want to argue that they’re not, you have to argue that Nigeria shouldn’t matter to readers of European and U.S. newspapers. And I think it’s a somewhat short-sighted argument. Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa. 180 million people live there. A lot more people than live in France, about three times as large. Boko Haram looks like it’s become a real threat to the stability of Nigeria. I think we have to ask ourselves why we aren’t covering in a serious, sustained way, an attack that could kill 2,000 people. We may find ourselves looking back in time, the way we looked at things like the Rwandan genocide, and saying, ‘Were we trying to do enough to report on this and to stop this?’

BROOKE: You wrote that the hundreds or thousands dead in Baga demand our grief as fellow human beings. And they demand our attention so we understand the shape of religious extremism in the world. Explain.

ZUCKERMAN: If we spend all of our time looking at religious extremism and assuming that it’s attacks like the ones in Paris, we get it wrong. If we conclude that that’s what terrorism looks like, Islamic extremism becomes a war against modernity. It becomes a war against urban elites. It becomes a war where we are the target. It’s a very scary narrative, and it’s a narrative that sells newspapers. But it’s not the right narrative. Most people who’re victims of Islamic extremists, are poor Muslims in developing nations. As many as 90 to 95 percent, according to the U.S. Center for Counterterrorism. These are local conflicts that have a religious component. The struggle with ISIS has a lot to do with local power in Syria and Iraq, with who’s going to control those territories. In that sense, it’s not dissimilar to what’s going on in Boko Haram. Groups in Northern Nigeria think we want to have our own Islamic State. Lumping that together, trying to turn this into global Jihad against the West and modernity, as Bill Kristol did when he tweeted at me demanding that I, you know, condemn Boko Haram as part of the same phenomenon as Charlie Hebdo, completely misunderstands the situation.

BROOKE: Ethan, thank you very much.

ZUCKERMAN: Always a pleasure, Brooke.

BROOKE: Ethan Zuckerman is director of the Centre for Civic Media at MIT.