Where Political Reporting Goes Wrong

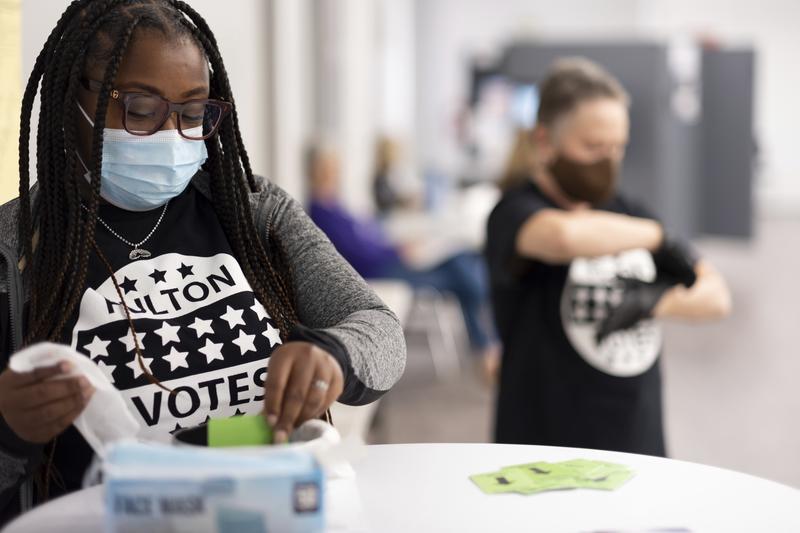

( Ben Gray / AP Photo )

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York. This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. On Tuesday, Donald Trump announced his third run for the presidency at Mar a Lago in what he'd have called a low energy hour if he hadn't been delivering it.

DONALD TRUMP Our country is being destroyed before your very eyes.

BROOKE GLADSTONE This on the heels of a week long defenestration of MAGAism and its leader by the press. 14 candidates endorsed by Trump, who once said that with him in charge would all get tired of winning – lost. Leading to the best midterm result for a president in decades. Since then, the pundits have been asking.

[CLIP MONTAGE]

NEWS REPORT Is Trumpism over? I mean, the donors are running away. The Murdoch media are moving away.

NEWS REPORT Donald Trump's moment has come and gone. That window is closed.

NEWS REPORT This is a deeply damaged ex-president like I haven't seen. Now we're talking about him being a mixture of Warren Harding, Andrew Johnson.

NEWS REPORT Trump is a joke. He lost the house, the Senate and the White House. He's lost the popular vote twice.

NEWS REPORT And I'd like to think that the Republican Party is ready to move on from somebody who's been. For this party a three time loser. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE But if the GOP is ready to move on from Trump, it'll be tougher to move on from Trumpism. Tom Scocca wrote this week in The New York Times that it's difficult to, quote, declare defeat for a movement that is built around refusing to accept defeat. He said that though some may call Trump a loser. They haven't yet gathered up the courage to find another, less Trumpy way to win. Even so, Trumpism has over is the dominant post midterm political narrative. Of course, political reporters were singing a different tune prior to the vote. Something about an inevitable red wave in a democratic climate that could be described only as bleak. And I mean only.

[CLIP MONTAGE]

NEWS REPORT The economy now a top issue in the midterm elections, less than six months away, with Democrats chances looking increasingly bleak.

NEWS REPORT A new poll from ABC News and The Washington Post explains why the midterm landscape is so bleak for Democrats.

NEWS REPORT A final CNN snapshot of the midterm climate and it is beyond bleak for the Democrats as the president and the Democrats remain in complete disarray ahead of the midterms. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Oh, I forgot about Dems in disarray. That was very popular.

JAMES FALLOWS You have to view the New York Times as the outstanding news organization of our era. That is why is with enormous respect for its influence that I've noted, the things where in politics it has seemed to consistently steer US media discussion in an unfortunate direction.

BROOKE GLADSTONE James Fallows has been writing about the jarring gap between reality and the predictions of political reporters for 40 years. He also writes the Substack newsletter, breaking the news.

JAMES FALLOWS As soon as the very first results came in on Election Day, which were from those gerrymandered districts in Florida that Ron DeSantis had set up, and that flipped Republican. The New York Times put out an early edition whose banner headline was GOP Collects Early Wins in Pivotal Vote and the two above the fold stories. One was an explainer saying Allies wonder why America can't fix itself. And the other one was saying Democrats faced intense national headwinds. They were so spring loaded to interpret what was going on that even on election evening as people were voting, in fact, for the best incumbent results in 50 years in midterm elections, they were prepared to interpret this as why can't America fix itself?

BROOKE GLADSTONE As you noted, what happened in reality appeared to be entirely at odds with what the political reporter cadre across the media had been preparing the public for. So how did the coverage of these midterms compared to prior election cycles?

JAMES FALLOWS There are two standards of comparison that I find interesting. One is an admittedly unfair standard, which is how this is going to look in, quote, history, unquote, because it seems already clear that some of the fundamentals of this election, for example, a very strong vote for women based on the Supreme Court's Dobbs ruling and the changed abortion landscape, and a sense that on economics, it wasn't strictly the price of gasoline, which we heard about ad infinitum, but also the job market, which was very strong. Joe Biden's speeches about democracy, which were widely ridiculed by the press, actually seemed to have gotten some traction. And almost all of the election deniers and sort of Trump-weirdos, if I can use that category for a lot of the candidates – they lost. Leading up to the election, it was all prices at the pump, Biden is unpopular. Hangover from Afghanistan which remember a year and a half ago was going to be the end of his presidency. There was a really fundamental mismatch between what seems to have been going on there and what our experts were telling us.

BROOKE GLADSTONE I'm wondering where these narratives come from.

JAMES FALLOWS I would enumerate three streams. One is whatever is happened to political polling, that seems as if all the fallibility of polling, whether it's not reaching enough, young people not getting enough answers overall, people not answering honestly, they seem to have cumulated in a number of really large scale errors. There seems also to be a sort of self-sustaining narrative within a number of the political press corps that my good friend Timothy Crouse wrote about 50 years ago when his son.

[BROOKE LAUGHING].

[BOTH SAY "BOYS ON THE BUS"]

JAMES FALLOWS Yeah, this was actually the election of 1972. And Tim Crouse wrote The Boys in the Bus about the way a narrative would evolve. And I think back then a guy named Walter Mears was the AP correspondent. People would say, okay, what do you think the narrative is after a speech by McGovern or Nixon or whatever, and you'd say, Yeah, the speech was X, and that became kind of the narrative. And we have the modern era of that. I think where certain narratives 'Biden is unpopular,' it's all about 'prices at the pump.' 'Trump is unstoppable.' They became the modern version of the boys on the bus.

BROOKE GLADSTONE That single word analysis has prevailed in all the ensuing elections. 'Al Gore was a liar.' 'George W Bush was a dummy.' 'Hillary Clinton was an emasculating–'.

JAMES FALLOWS –is unlikable. And also her emails.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Oh, and her emails. That was a narrative that the Times made great use of. And I mark that down to fairness bias. It's a kind of both sides-ism, and it's because the legacy press is still upset about being labeled liberal, starting with Richard Nixon all those years ago. Still trying to overcompensate to report two issues as if they're equal when they aren't and never were.

JAMES FALLOWS It's just a matter of observed fact that more people who go into the press as their career are politically liberal than not. You know, why do you go in this line of work and not become a financier and out of self-consciousness of that reality, and also because of relentless criticism from the right of 'oh your liberal bias' a lot of mainstream organizations want to make sure they have on Marjorie Taylor Greene, along with Jamie Raskin, as if these were people of comparable weight in what they're saying. And I think that was especially the case in the 2016 election where it seemed so, quote, certain, unquote, that Hillary Clinton would win. That mainstream outlets wanted to show that they were fearless in criticizing her, thus her emails.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Now I'm curious about the narratives that are emerging post midterms. In The New York Times, I saw a really good opinion piece by Tom Scocca, who described the temptation by some reporters to declare that, quote, the strength of the MAGA forces is ebbing at last. The calendar leaf is turning over on the Trump era. I have heard so many times this is the thing that'll sink it. That's the thing that'll get them and so on.

JAMES FALLOWS On the one hand, you're like, I'm setting this up. On the one hand, there are indications of some greater normalization of politics. One might have guessed two weeks ago that if, for example, Kari Lake were losing in Arizona or Dr. Oz or any of these other characters, Blake Masters, there would have been all these widespread protests and election denial and things we saw after Trump's defeat in 2020. And so far we haven't seen that as you and I are talking. So that could be some sign of normalization.

BROOKE GLADSTONE I just think that that is a weariness with Trump and not an exhaustion with Trumpism.

JAMES FALLOWS 'Yes, and' as we say. Yes, and this kind of Trumpism has always, always, always been part of the American makeup ramped up or damped down by different leaders at different stages of history. Obviously, has been ramped up to a truly rancid degree in the last six or eight years, as it was by George Wallace a generation ago and others before that. And so if even Fox is turning its back on Trump and seeing him as sort of past his sell by date, the sentiment will still be there. And the question is whether somebody else will emerge with the same talent at ramping it up.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So what are the post midterm narratives that you think maybe people ought to take a moment?

JAMES FALLOWS The post midterm narrative I'm against even more strongly is looking instantly to the 2024 lineup. If there were a single thing I could change about the political press corps, it would be to reduce by about 90% the effort, space, assignments, energy, etc. to what is going to happen two years from now or four years from now and switching them instead to what is happening right now. If you look back to any previous presidential election and try to correlate what is said right after the midterms with what happens two years later, there's basically zero correlation between who people think is strong and weak and rising and falling and just just forget about it. And instead, tell us more about what it was that made people vote the way that they did. So, for example, a thought experiment. You recall how after Trump's election, some of our leading newspapers we won't name had what we think of as the guy in the diner crusade of saying, Oh, how did we miss people who voted for Trump by this hair's breadth margin? And we could maybe have not the guy in the diner, but the woman in an office narrative of what it was that shifted the vote as fundamentally that made things not turn out the way all the reporters thought, over the last couple of months. And I'd like to hear from more of the people about the complexities of people's motives in voting, how they did.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Talk to me a little bit about the business of prediction. You wrote the book, Breaking the News 26 years ago about how strong this impulse is.

JAMES FALLOWS I understand why people in our business, the politically-minded media, like predicting things. It's always interesting to think who has the combination of intangibles and luck that might end up with that person being president. That is the fun part of our game. The challenge is that it's both cheating and it's not useful. It's cheating because it reduces everything to an area where people in our business are the supposed experts rather than what are the economic fundamentals, how does this person work with colleagues? What has this person done? What kind of personal characteristics does he or she have? Etc., etc.. So it moves the playing field away from all the vast 3D reality of life to a flattened 1D reality of politics. It's also just not useful, and it's not even as accountable as being a Las Vegas sportsbookie. The sports bookies or the crypto investors, they finally have to cover their losses. You don't have to cover a loss if you are saying Person X is going to be president and that person is not. You just say, Well, any surprising result? Blah, blah, blah. And it's just a surprise.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And it's contrary to expectations because it's these political pundits that establish what those expectations are.

JAMES FALLOWS It was like an Olympic ice skating move of landing, a quadruple axel or whatever. The same exact people who, a day before the election were writing about the red wave were the day after the election, saying which many people had expected to turn into a red wave instead. But that's not saying many people, including me, I think in many other fields there would be at least a pause to say, let's recalibrate here.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You know, we once reported on a study that found that the number of appearances that a particular pundit had on television was inversely proportional to how accurate their predictions were. The more wrong they were, the more likely they were to be invited back. No one wants to hear on the one hand. On the other hand, someone saying with great passion, something extreme is just better TV. So when it comes to print, have you seen any publications who have self corrected post midterms?

JAMES FALLOWS Let's take an example of Andrew Sullivan, once my colleague at The Atlantic for a while, and he did very forthrightly do a 'I was wrong' piece after the midterm election saying that all of his woke narrative was excessive and rising crime narrative was excessive, and he hadn't taken either abortion or democracy seriously enough. I've seen a couple of other people do limited versions of that, but institutionally it would be worth it for our colleagues, again speaking you and me and the press to say the kind of after action report you get in medical operations or whatever when there's a problem to say what went wrong here and how can we account to our public for things where we didn't do what we thought we were doing?

BROOKE GLADSTONE So you're recommending that the press just take a timeout from predicting?

JAMES FALLOWS Yes, I'm saying that I had actually a little little formula, which was for an assignment editor or a writer for every 3 times the impulse comes up to say, let's follow Ron DeSantis. Let's follow the next six people who might be contender in 2024. For every 3 of those impulses, shunt off two of them to a story about the actual world of the now. Of its culture. Of its economics. Of its technology. Of something else. Of its sustainability. Don't predict the future, which you don't know. That is my timeout suggestion. It might be nine out of ten, but I was gently suggesting two out of three.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And the chances of that. Any predictions?

JAMES FALLOWS [LAUGHS] Well done, Brooke. Talk about landing the quadruple axel. I would predict zero out of zero. I hope that in surprising results in results then that many observers did not expect, we'll see a diminution in predictions.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Thank you so much, Jim.

JAMES FALLOWS Brooke, it's a pleasure to talk with you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Coming up, Twitter in disarray. This is On the Media.