When Snow Came to San Juan

David Remnick: This is The New Yorker Radio Hour, I'm David Remnick.

[music]

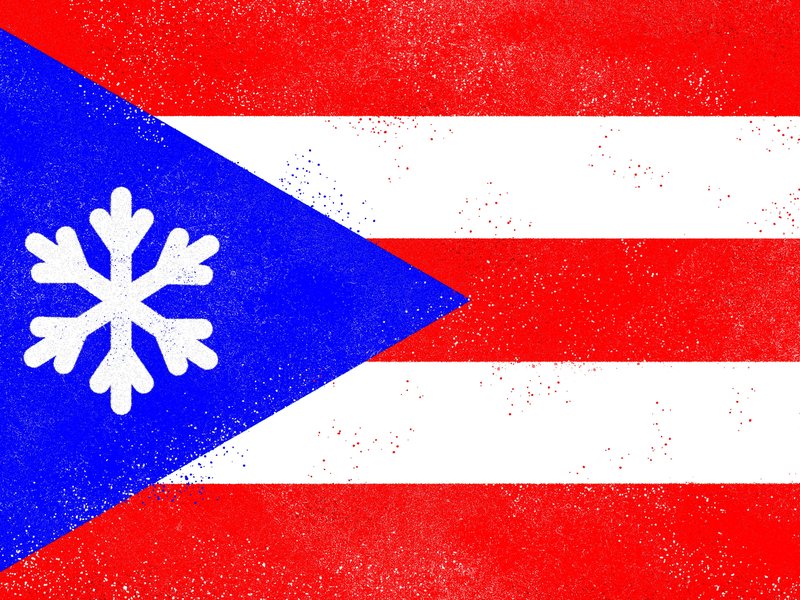

David: The way things are going on this planet, I've got to wonder if one day people will have to take their kids to Barrow, Alaska, or Greenland in order to see a white Christmas, somewhere north of the Arctic Circle. Since the beginning, Christians all over the world have managed to celebrate the holiday without sleigh bells and without snowmen. Alana Casanova-Burgess is the host of La Brega. She brings us a story about a very unusual holiday occurrence. Not quite a miracle, but close. For several years in the early 1950s, Puerto Rico received snow right around Christmas. Alana spoke to people who saw it with their own eyes.

Alana Casanova-Burgess: Many years later, as he sat for an interview, Ignacio Rivera was to remember that distant morning when his father took him to discover snow in San Juan.

[music]

Ignacio Rivera: I thought that it was almost impossible for me to have seen snow. At that time, it was something that like came from the moon. Something strange, like going to Mars, something out of the imagination.

Alana: It had been announced in all the newspapers, "snow was coming." It was the early 1950s. Ignacio was around eight years old living with his parents in Barrio Obrero.

Ignacio: From watching movies, I know snow was white, but I had no idea what cold was because I had never been exposed to under 70 degrees in my life. You don't know how it falls, how it accumulates, how it turns into ice once it starts to melt.

Alana: It came, real fluffy snow, cold and fresh from the slopes of the Northeast brought to a city park for a snowball fight.

Ignacio: I simply enjoyed myself. I had a snow fight with my friends, something that we knew we would never see again because that was a one-shot deal.

Alana: It actually wasn't a one-shot deal. For four years in a row, kids in Puerto Rico were invited to the snowball fight in the tropics, to see snowmen assembled under palm trees. For a brief moment in the early 1950s, it was a miracle that kept happening.

Ignacio: Magnificent, magnificent. Maybe there was a subliminal message there which I begin to understand at the tail end of my life.

[music]

Alana: If you've read 100 Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, maybe the snow in the tropics sounds familiar. The first sentence is one of those iconic lines in literature. "Many years later as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice." This happens in Macondo, a fictional town somewhere in the Caribbean. We never learned exactly how the ice got there, or where it came from, or how long it lasted in the tropical heat. In the novel, the ice is a symbol for a kind of wonderous progress, but also for something existing where it doesn't belong, a kind of dark magic. Here in the real world, Macondo is shorthand for any surreal place where the unexplained is routine.

Ignacio: Embracing a place where the most impossible things can happen, and people get used to it and they don't even get affected by it.

Alana: Ignacio is a defense attorney and political commentator based in Puerto Rico, which, as it happens, people call Macondo all the time.

Ignacio: If we saw a flying saucer land right now in San Juan, half of the people wouldn't even blink an eye because we're used to the extreme economic and social collapse of the country.

Alana: In Puerto Rico, potholes are so big that people put Christmas trees in them to warn other drivers. Shuttered school buildings are taken over by vegetation, as though by force. It's not quite true that nobody blinks an eye when these kinds of things happen. The absurdity is maddening, frustrating, stifling. There are protests and a level of austerity that nobody can get used to. Unlike in the fictional Macondo where bizarre things happen for no reason, Puerto Rico's weirdness is often a function of a broken government and of the colonial relationship with the US. There are people in power who are responsible, who make decisions that affect people's lives. Even though we never learned how the block of ice came to Macondo, I can tell you how snow came to San Juan and who brought it there.

Felisa Rincon de Gautier: My population is about more than half a million.

Ignacio: Half a million people just in the city of San Juan.

Felisa: In San Juan [unintelligible 00:05:19] which is to compose in whole San Juan.

Alana: This is Felisa Rincon de Gautier, known in Puerto Rico as Dona Fela or Dona Felisa. She was mayor of San Juan for 23 years, starting in 1946. She was considered an incredibly effective politician. For example, she developed a preschool system that was the model for the Headstart program in the States. She also expanded healthcare in the city, as she told WNYC during a visit to New York in 1957.

Felisa: The physical facilities are not as good as I want, and I am working for the plan for a new hospital.

Alana: If she was a populist, she didn't look it. She had studied fashion design in New York and owned a clothing boutique in Old San Juan before running for office. She wore strings of pearls and elaborate gowns. Her long hair, first blonde, later Gray was braided and coiled on top of her head, defying gravity and also humidity. She looked like an older Marie Antoinette if Marie Antoinette also wore sunglasses.

Ignacio: Like a queen, I'm imagining that poor country when you dress like that you stand out.

Alana: Ignacio remembers her vividly.

Ignacio: People want to be like her. She played that role all the way till she became extremely old and retired. She was a very elegant woman.

Alana: Hilda Rodriguez was Dona Fela's assistant for 20 years. She's 96 now. We connected in a shaky Zoom just after a blackout in San Juan.

[foreign language]

Hilda: [foreign language]

Alana: She says the mayor was extraordinary, incomparable. Hilda kept Dona Fela's calendar and organized official trips. She remembers the mayor going to John F. Kennedy's inauguration. There was one invitation that would cement the mayor's legacy.

[music]

Alana: It was 1952 and an executive from Eastern Airlines asked if she'd come to a big company conference in Florida.

Hilda: [foreign language]

Alana: 400 delegates, only three were women. Hilda says that Dona Fela would be the keynote speaker. When they arrived, the executive approached Hilda with a message, "The head of Eastern Airlines would like to thank the mayor for coming with a gift."

Hilda: [foreign language]

Alana: "Maybe a watch, would Dona Fela like a watch?" "Absolutely not," Hilda said. The mayor did not accept gifts. After the speech, she was approached yet again.

Hilda: [foreign language]

Alana: "Give her only flowers, nothing more." she told the mayor, "Look, this Eastern Airlines guy is being very persistent." Dona Fela said she'd think about it. At breakfast the next morning, she had a request. Snow. She wanted him to figure out how to bring snow to the Caribbean.

Hilda: [foreign language]

Alana: As we talked on the Zoom, I could see Hilda put her hands up to her face, mimicking Dona Fela holding a ball of imaginary snow, sucking on the cold. The mayor remembered that joy from living in New York. "I want you to take snow to my kids," She said. Hilda says she'll never forget the look on the man's face when he heard the request.

Hilda: [foreign language]

Alana: That was a Saturday. They got back to Puerto Rico on Sunday. By Wednesday, Eastern Airlines was calling. They would bring her snow.

[music]

Alana: In San Juan, it was in all the local papers.

Ignacio: My father was a public servant and he said that the mayor of San Juan, Dona Felisa, was bringing snow to Puerto Rico.

Alana: In 1952 that first year, the snow arrived in March. In future years, it came on Three King's Day, January 6th, at the height of the holiday season. Here's how it happened in 1953, according to one local paper. In Pico Peak Vermont, two tons of snow was prepared for its journey. An article in the Rutland Daily Herald claimed it would be packed by local kids as a gift for the children in San Juan. Snow untouched by adult hands. The snow went into insulated bags that could hold 10,000 snowballs, no mention of how that calculation was made, and a snowman in parts ready for assembly. Then the bags went into a refrigerated truck bound for a New York airport, where they were loaded onto a four engine constellation airplane packed into a aluminum canoe.

Ignacio: A big gigantic, like the trailer truck size. It was full of snow.

Alana: It was attached to the bottom of the plane, a belly boat. Once it arrived in San Juan, that canoe was put on a trailer and driven just a few minutes to Puerto de Tierra, a strip of land that connects the peninsula of old San Juan to the rest of the city. Thousands went to a park there to receive it.

Hilda: [foreign language]

Alana: It was unforgettable. Ignacio remembers he and his friends were so excited they couldn't wait for the snow to be unloaded.

Ignacio: I was not that disciplined so a bunch of my friends jumped inside the container. We had a snow fight with the guys outside. I began to realize that tennis shoes are not the best thing to be stepping on snow because they tend to get very cold but I have no idea what cold was so we have to learn the hard way.

Antonio Martorell You learn fast, and I had seen pictures and the movies and whatnot.

Alana: Antonio Martorell was 11 or 12 when he made his first snowball from Donya Fela's snow. He grew up to be one of Puerto Rico's most famous living artists. His portrait of Dona Fela is part of the collection in the National Portrait Gallery in DC and he remembers that she through the first snowball ever thrown in Puerto Rico.

Antonio: [foreign language]

Alana: Thus began a pitched battle that made for some quirky news back in the States.

Speaker 1: It's a race against time to enjoy this pawn importation, for the mean temperature here is 73 degrees so gather you snowballs while you may. The thermometer is too uncooperative.

Alana: In this news reel from 1955, you can see hundreds of kids packed together with a flurry of white being hurled at short range.

Speaker 1: A snowball fight to end all snowball fights for 10,000 youngsters seeing this fleecy stuff for the first time.

Alana: The snowball fight isn't trench warfare. It's more a hand to hand combat. Men with shovels spread the snow on the ground. A boy in short sleeves zooms by on a sled. Donya Fela is tossing it into the air, her up-do perfectly intact, enjoying herself, but the star of the news reel is not Puerto Rican at all. She's a tiny ambassador for this white Christmas.

Speaker 2: To San Juan Puerto Rico from new Hampshire's white mountains comes 12 year old Nancy Conway, the snow princess. Nancy is bringing to this to this torrid zone Commonwealth commodity unknown here but plentiful in Nancy's home state transported by airplane.

Alana: The snow princess comes down the airplane steps in a cable knit sweater and a winter hat. Dona Fela and couple of kids in traditional costumes greet her. Watching it, you wonder how much snow is melting during all that pomp and circumstance. Do you remember trying to taste it?

Ignacio: Yes, I did, I ate it. It was ice, a big surprise . I Puerto Rico we put flavor to the piragua, which is a cone of ice.

Antonio: With a syrup, with a sugary flavor on top of it, and it's delicious.

Ignacio: It didn't taste like my piraguas. It tasted like nothing, like water, which is what it is.

Antonio: What's the sauce? Just nothing to it, tastes like nothing.

Alana: Ignacio recalls the delight of the snow lasting hours and so does Hilda, but not Antonio.

Antonio: Because it melted right away, melted right away. Didn't have much time to enjoy it. I think it was about all together about 10 minutes, that was it.

Alana: He remembers all the kids showed up wearing white.

Antonio: [foreign language]

Alana: As the snow melted, everything turned to mud and the illusion melted in their hands.

Antonio: We saw that the dream turned into a nightmare, that the snow melted into mud.

David: That's the artist Antonio Martorell speaking with WNYC's Alana Casanova Burgess. Our story continues in a moment. This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. We'll continue now with a story of how snow came to San Juan Puerto Rico in the 1950s. A gift from the city's mayor and delivered by Eastern Airlines, which milked the publicity for all it was worth. It didn't cost the people of Puerto Rico much at all. You could say the snow came with other strings attached though. WNYC's Alana Casanova Burgess picks up our story.

Alana: Even before the snow arrived, there was plenty of Christmas magic in San Juan. Street vendors would throw an orange peel up in the air. The shape it made on the ground would be like a love spell.

Antonio: That letter would be your boyfriend or your girlfriend or the one you were supposed to marry. It was great.

Alana: The holidays in Puerto Rico last from Thanksgiving through Christmas, then through Three King's Day and all the way to San Sebastian, a festival in late January.

Antonio: We felt privileged in that way and we still do, because we have not only one Christmas, we have two.

Alana: By the early 1950s, hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans had moved to the States, part of a massive wave of migration. Antonio and many other kids on the island were already getting reports from cousins about the glories of American Christmas. Of course, those reports were often exaggerations. Nobody wants to tell their family that they're struggling in some far away frigid city. Yet to Antonio, it still felt like there was a message about living in the colony, that it was a second class Christmas, even down to the weather.

Antonio: the leaves didn't change. It was a little cooler than rest of the year, but not that much. We did feel that it wasn't a privilege to have this tropical climate. We felt really underprivileged .

Alana: Over the decades, Antonio came to see the snow not simply as a wondrous discovery-

Antonio: [foreign language]

Alana: -but as an attempt at assimilation.

Antonio: [foreign language]

Alana: A sign that being Puerto Rican was to be less than, what he calls the colonized mind.

Antonio: Not only snow was better than sunshine, but also English was better than Spanish, being white and blonde was better than being dark and Puerto Rican and being in the north was better than being in the south. Of course, it had all had to do with person of privilege, be it true or imagined.

[music]

Alana: All of this wasn't only a matter of culture or psychology. It was politics, and it was brutal. In the early '50s, there was severe violent clashes between the independence movement and the government. Wheels were in motion to make closer ties with the US seem like the best option and the snow was literally blanketing over that tension. The first year the snow came, 1952, was critical. It happened in late March, just a few weeks after Puerto Ricans approved a new constitution that would change ever so slightly their relationship with the United States. Puerto Rico would be rebranded as a Commonwealth, or a Estado Libro Associado. A free associated state, which yes, doesn't mean much. Today there's widespread understanding that it's not the same as self-government.

Puerto Rico is still a United States colony, regardless of the rebranding and Donya Felisa supported. Hilda, her secretary, says the snow wasn't about that. It wasn't a political manipulation. It was just that the mayor loved snow. Antonio says, "Yes, but-"

Antonio: All politicians, at least most of them, are colonized themselves. More so even than most people.

Alana: It's worth remembering that Puerto Rico in the 1950s was a place of intense poverty, it still is. San Juan had vast slums with no running water. The arrival of the snow, this extravagant fantasy come to life was yet another sign of the might and wealth of the US, and it furthered this promise that staying close to the empire would lift Puerto Rico out of poverty. 70 years later, that's still not the case.

[music]

Alana: When Hurricane Maria tore across the Island, it knocked out the entire electric grid. Four years later, there are still blackouts constantly. The system was recently privatized and the cost of energy is going up while the service is getting worse. Then, just last month, there was a headline that seemed ripped from Macondo. The mayor of [inaudible 00:20:31], a town in the Lush Mountains in the center of the island was going to use $100,000 of COVID-19 aid for the creation of an ice skating rink, at a time when electricity is at such a premium and people are struggling to keep their insulin refrigerated.

Ana Teresa Toro: When there's another blackout, and it usually happens in the middle of the night, so you wake up because you are sweating.

Alana: Ana Teresa Toro is a journalist a novelist based in Puerto Rico.

Ana: The first thing I do is to take off my baby's pajamas because he's sweating even more than me. I will put a little bit of fresh towels with a little bit of water and then we wait for the morning because usually you cannot sleep anymore.

Alana: She lies awake, her mind turning over the questions. Will daycare be canceled? Did she buy too much food the last time she went to the supermarket, will it rot?

Ana: Is this going to last a few hours or is this going to last a few days? There's uncertainty. Everything in your work week goes off the rails and there's a feeling of, you feel defeated because you start thinking things that I don't want to think. Why do I even bother? Then you start looking around and you realize that it kept moving and you feel left behind. Of course you could say, "Well, I could leave."

[music]

Alana: Ana Teresa lived for six months without electricity after the hurricane. Some people, like my aunt, lived a whole year without it. I remember visiting her and thinking about another part of 100 years of Solitude. The residents of Macondo, the fictional Macondo, are afflicted with insomnia and they all begin to forget the names for things. They have to label objects with notes. Like, "This is a chair. It is for sitting. This is the cow. You must milk her every morning." I looked around my aunt's home and saw the oscillating fan useless without electricity. This is a fan. It used to keep us cool.

This is a television. It used to show us movies. This is a light switch. This is a refrigerator, a washing machine, a cell phone charger, a lamp, and on and on and on. When nothing works, people leave. Puerto Rico has lost over 10% of its population in the past 10 years. People wonder openly in newspapers, on the radio, on Twitter if the government is actively trying to make life impossible for Puerto Ricans, if rich people from the United States are welcome to pay less in taxes and develop the Island's coastline while everyone else is standing in line waiting to buy bags of ice.

Ana: Anyone from Puerto Rico that went through Hurricane Maria will have different relationship with ice. It changed radically. Maybe I was eight hours waiting for the ice and it lasted three or four.

Alana: In a Caribbean climate there's nothing more delicious than the feeling of cold, even the memory of cold. There's a different story about snow in Puerto Rico that has stayed with Ana Teresa, a story that has shaped her idea of what it means to be Puerto Rican. The big mall in San Juan is called Plaza Las Américas. Every Christmas it has this elaborate display of fake snow. Eight years ago she went to write an article about it and she had a pretty good idea of what she thought.

Ana: Look at the palm trees full of fake snow. This is so ridiculous, to have fake snow in here and this is stupid. Why are people coming to see this? Oh, my God. There was this woman who came from Moca, that's like an hour or so, a little bit less than an hour to San Juan. She was with her two kids and I was like, "Look at this woman. How could she come from Moca with her two girls? They are supposed to be in school, and to see the fake snow? How could people do this?"

Alana: The woman explained that she grew up in New York. The daughter of that generation of Puerto Ricans who moved to the States in the '40s and '50s who would've told their cousins about the beautiful snow at Christmas. In the '70s many of them moved back to the island and brought their US born kids with them.

Ana: She told me, "I have no money to take my daughters to New York to show them how was my Christmas. This is the only chance I get to share with them this very special memory of my childhood." Every time I remember that I get goosebumps.

[music]

Alana: There's a saying that Puerto Ricans are Puerto Rican wherever we are, even if we're born on the moon. As long as people have roots in Puerto Rico, Ana Teresa says, as long as there's a love there.

Ana: Now every time I go to Plaza Las Américas, I even stay a little bit. I look at the fake snow with tenderness, with emotion, because I remember that, yes, it's a spectacle. Yes, you could give it the colonial lens to read the experience but also there are human stories behind that that we have to respect and that we have to embrace as our own because Puerto Rican history has a lot of snow in it.

David: That's Ana Teresa Toro talking with Alana Casanova Burgess. Alana is the host of La Brega from WNYC studios and Futuro Media.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.