When Hip Hop Tried to Fight the Power, and Lost

[music]

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

[music]

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright. This year marks the 50th anniversary of hip hop, five decades between the moment that hip hop emerged from a youth scene in the Bronx as this scrappy art, and what we now know as a multi-billion dollar global business. This week, we look back at one chapter in that long, remarkable story, a time in the late '80s and early '90s when the music became a platform for a particular set of pro-Black political ideas that shaped kids like me.

Producer Christopher M. Johnson takes us back to that era and asks, where'd it go?

Christopher Johnson: Kai Wright.

Kai Wright: Christopher Johnson.

Christopher Johnson: Where did you grow up?

Kai Wright: I grew up in Indianapolis.

Christopher Johnson: Did you get into hip hop when you were a kid?

Kai Wright: I did. I wasn't like one of those heads. I wasn't like steeped in any music. I just remember the Fat Boys. I could say that was the first like group I was like, "Yes, Fat Boys are back!"

[MUSIC- The Fat Boys: The Fat Boys Are Back]

Christopher Johnson: I've never heard anyone say Fat Boys was their like entrée into hip hop. I'm not knocking it. That's just different.

Kai Wright: That's just-- It may have been because I was young, and they were silly and fun.

Christopher Johnson: Do you remember when you started getting into hip hop that was maybe a little more serious or even political?

Kai Wright: A little more advanced?

Christopher Johnson: Well, not advanced, just different.

Kai Wright: It's Public Enemy, and you're like, whoa.

[MUSIC- Public Enemy: Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos]

Christopher Johnson: What was it about, especially about Public Enemy's music, and their style or whatever, that drew you in?

Kai Wright: They had this stuff to say, and I was of an age like, what do I have to say? What do I think of the world? I was going to white schools, and so I had been experiencing this stuff around race my whole life, and here was people who were having a conversation about it. I don't know. It hit right at the right age for me where I sucked it up.

Christopher Johnson: Yes, you and me both, man. Then you had A Tribe Called Quest and Jungle Brothers, and De La Soul, this black bohemia, invoking Black Pride and Africa, aka The Motherland. All of these groups were part of this musical movement that came to be known as "conscious rap."

Kai Wright: Right, and looking back at that moment, I wonder where it came from. Because the thing is, it really was important to me. As a young Black person trying to figure out the world, this music was a big part of how I did that, and developed this sense of being proud in like my Blackness as a political identity.

Christopher Johnson: I was actually wondering the same thing. Of course, there's definitely political and social consciousness and rap music today, but this era, the one that we're talking about now, this was the first big wave. It was dealing with what our communities were really going through. What I wanted to know was, where did that consciousness in conscious rap come from? Then where the hell did it go? You know what I did?

Kai Wright: What?

[MUSIC- Kool Moe Dee: How Ya Like Me Now]

Christopher Johnson: I called up the Kool Moe Dee.

Kai Wright: Shut up.

Kool Moe Dee: Mic check, one, two. Kool Moe Dee. I was born a Leo!

Christopher Johnson: You hear folks talk about old school rap. Well, Kool Moe Dee started rhyming in 1977. This is when hip hop was still this punkish, insular party and art scene in New York's underground.

Kool Moe Dee: I come from the school of hip hop where it's literally two turntables and microphones and no routines or whatever ahead of time, so you really had to earn your audience.

Christopher Johnson: Hip hop is street music, and in the early 1980s, hip hop started zooming in on social problems. Like the rest of the country, New York was crawling out a two national recessions. There was a double-digit spike in unemployment. At one point, nearly 1 in 5 Black New Yorkers was jobless.

Then in 1982, here comes Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five with their classic, The Message.

[MUSIC- Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five: The Message]

Kool Moe Dee: I think that was the first time we even saw hip hop in a space that was outside of just partying. Starting to talk about things in the neighborhood was something that was bubbling, but it wasn't a lot of pop success with that.

Christopher Johnson: Then, in 1988, Public Enemy dropped their second album, It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back. This is considered one of the greatest rap records ever. Militant, pro-Black, anti-crack hip hop. Peak conscious rap.

[MUSIC- Public Enemy: Bring the Noise]

Kool Moe Dee: Once everybody saw that it could be successful, then it became the best of both worlds. You could have the pop and commercial success, and still talk something conscious.

Kai Wright: There was a lot to be conscious about. This was the mid-1980s. Crack cocaine is raging. There's all the addiction, there's all the war on drugs that's coming out of that, and death, and everything in its wake.

Christopher Johnson: Yes. I went looking for this time when hip hop artists answered a call to action. When they used their art and their voices to push for social change. I found that moment. This is 1988, Kool Moe Dee goes on this big tour.

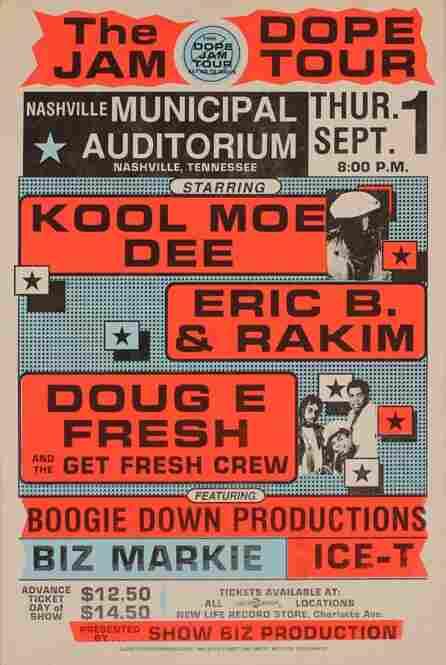

Kool Moe Dee: It was called the Dope Jam Tour. It was a headline by myself, Rakim, and Doug E. Fresh.

Christopher Johnson: Biz Markie performed a Dope Jam, so did KRS One, Ice T, Big Daddy Kane, all artists who either were or would soon become some of the biggest names in rap music.

Kool Moe Dee: We literally were having, I could say, kid in a candy store kind of fun, laughing and telling each other what we loved about each other, so it was that kind of summer.

Fab 5 Freddy: Yo! Fab 5 Freddy. We’re up in the Yo! MTV Raps. I got a mega posse chillin with me right now.

Christopher Johnson: Dope Jam makes its last stop on Saturday, September 10, and it's booked at an arena about 25, 30 miles east of Manhattan.

Hip hoppers came from all over New York for Dope Jam. Ann Carli was one of them. As an executive for Jive Records, Ann went to a lot of hip hop shows. She knew this crowd, mostly Black and Latino, young, and mad stylish.

Ann Carli: People dressed up. You wore your best clothes, your best coat, and your gold chain and everything like that.

Christopher Johnson: As Ann headed into the coliseum, she started to get her first sense of what this night was about to turn into.

Ann Carli: I saw a bunch of older guys that I was pretty sure weren't fans, and I actually said to my two colleagues, "Something's off here. You guys be careful."

Christopher Johnson: Ten thousand heads packed this coliseum, and right when the show was really getting hot, Kool Moe Dee, who's sort of backstage, sees these fights breaking out all over the coliseum.

Kool Moe Dee: There's a posse of guys running around snatching chains, literally scoping and looking and tapping each other and saying, "There's a girl by herself right there. We're gonna go take her pocketbook," and, you know, do what they're going to do. That's where the violence started very early in the night.

Dean Jones: One guy saw me with my gold on. He reached for my bracelet, so when I turned around, I grabbed him.

Christopher Johnson: A fan later told a film crew about all the madness that went down that night.

Dean Jones: I didn't realize I was stabbed until it was all over. When I go into the first aid office, it's crowded, full of people who'd been stabbed and cut.

Christopher Johnson: By the end of the show, a dozen people had been injured. The worst part of this, a 19-year-old Bronx kid was stabbed in the heart and killed.

Kool Moe Dee: I did hear that somebody died from the audience. I'm like, "Wow. To go to a concert and lose your life is absolutely ridiculous."

Christopher Johnson: Just to put this in a little bit of context, in 1988, this is the same year as the Dope Jam Tour. Nearly 1,900 people were killed in New York.

Reporter, Special News Report: Seven innocent people were injured in an August gun battle involving M16s.

Christopher Johnson: For a group of artists and industry people, that coliseum show and the way that the press covered it, this was the last straw.

Kurt Loder, MTV News: First, let's take a look at the news. The most disturbing story of the week was actually a recurring one: the alleged cause and effect connection between rap music and concert violence.

Christopher Johnson: One of the guys who was at Dope Jam, he's reading the coverage, and he is fuming.

Nelson George: My name is Nelson George. I'm a writer and a filmmaker.

Christopher Johnson: Nelson was the Black music editor for Billboard magazine.

Nelson George: This particular incident really irked me. I remember calling a few people, thinking maybe there's a way to do something about it. I remember speaking with Ann Carli.

Ann Carli: Nelson called me up and said, "Can you believe these headlines are blaming the music?" I said, "Nelson, I was there," and so we thought, "What can we do?" Because it's not the music. The fans didn't just erupt into violence by the music.

Christopher Johnson: Nelson wanted to set the record straight. "It was time for rappers to define the problem," he would later write, "and defend themselves."

Nelson George: How do we organize a community of hip hop to counteract the media narrative that rap equated to violence?

Christopher Johnson: Nelson and Ann started recruiting a small, influential group of industry people. They huddled at Ann's office in a New York City brownstone.

They called themselves The Stop The Violence Movement, and their goal was to use rap's growing influence and celebrity to try to counteract some of this violence. The group actually got inspiration from a pop song.

[MUSIC- USA for Africa: We Are The World]

Christopher Johnson: We Are The World had come out just a few years earlier. It features some of the biggest artists of the era, in chorus, on a charity record.

[MUSIC- USA for Africa: We Are The World]

Nelson, Ann Carli, and the rest of their organization decided that they would make a We Are The World for hip hop, featuring rap's leading voices sending a unified message both to fans, and to critics.

Nelson George: There was no precedent really for something like this. Certainly not in hip hop.

Ann Carli: There were people that I called in the industry who said, "You're never gonna be able to get this done. Rappers? Forget about it."

Christopher Johnson: The skeptics were wrong. Everybody wanted in. Some of the biggest, most popular names in rap got on board, including KRS One. He was a key member of the Stop The Violence Movement, and he laid down the song's first verse.

[MUSIC- KRS One: Self-Destruction]

Christopher Johnson: They called the song Self-Destruction. It was a who's who of late '80s rap. You remember Doug E. Fresh, MC Lyte, Chuck D.

[MUSIC- Kool Moe Dee: Self-Destruction]

Christopher Johnson: Kool Moe Dee. He dropped probably the most iconic verse on this song.

[MUSIC- Kool Moe Dee: Self-Destruction]

Nelson George: There was a sense of hip hop had a role in talking about what was going on in the community and what the role of the culture was in that.

Kai Wright: As I recall, this song had some critics, too, though, right? Not everybody liked it.

Christopher Johnson: Absolutely. Some folks argued that it promoted this idea of blaming Black folks for the violence and the neglect in their communities, without a real mention of structural racism.

Kai Wright: Which is a fair point.

Christopher Johnson: Yes, and Nelson accepts that point, but he still sees something bigger.

Nelson George: I feel like it set a certain example for what the possibilities of hip hop were. It was a statement about intention that needed to be made about what this culture could be at its best.

Christopher Johnson: From about this point, there's this real blossoming of conscious hip hop, from artists like KRS One, like Public Enemy. This culture just became saturated with all of these different expressions of Pan-Africanism, Black Pride.

[MUSIC- Public Enemy: Fight the Power]

Christopher Johnson: And, Black empowerment.

[MUSIC- Public Enemy: Fight the Power]

Christopher Johnson: All right, so back to my question. If conscious rap was so influential and it was so rich and so powerful, then how come it only lasted about six years, to like 1993?

[MUSIC- Ice Cube: Rollin’ wit the Lench Mob]

Nelson: Well, you know what Ice Cube said: "Self Destruction' doesn't pay the damn rent or f'in rent."

[MUSIC- Ice Cube: Rollin’ wit the Lench Mob]

Kai Wright: After the break, Ice Cube.

Christopher Johnson: [laughs] Unfortunately no, but--

Kai Wright: Well, sort of. We can talk about Ice Cube.

Christopher Johnson: We can. Yes, we're going to talk about Ice tea, that's for sure.

Kai Wright: Sorry.

Christopher Johnson: [laughs] Get your drinks straight, man.

Kai Wright: Either way, we'll be back.

Christopher Johnson: To figure out what happened to this first generation of conscious rap music, I called at this guy, Dan Charnas.

Kai Wright: One of the most well-respected scholars of hip hop.

Christopher Johnson: Absolutely. Dan was at the table when some important decisions about hip hop's fate were being made.

Kai Wright: What'd he say?

Dan Charnas: What happened starting in around '93 and '94 was the beginning of real mainstreaming of hip hop.

Christopher Johnson: There are two major radio stations--Power 106 in LA-

[Announcer: Power 106 air check: “We have a liftoff! Power 106. Oh, it’s go time.”]

Christopher Johnson: -and Hot 97 in New York.

[Announcer: Hot 97 air check: “The hot 97 summer mix weekend. We’re in the mix. Keep your radios locked, or listen on the where hip hop lives at.”]

Christopher Johnson: Both are owned by the same company, and that company decided in the early '90s to make them all hip hop, all the time. At first, the music is pretty diverse.

Dan Charnas: The stuff that succeeds is the stuff that really conforms to this kind of upwardly mobile, aspirational, capitalist theme. Because now major labels are involved, the search for the different stuff becomes sublimated to the search for the same stuff.

Christopher Johnson: There's another part of this conscious rap story, too. It goes back to 1991. It's an event that most folks just refer to as "Rodney King."

Kai Wright: Yes.

ABC News: The three police officers facing felony criminal charges were among a group of 15 who stopped a 25-year-old Black man last Saturday night, then beat him, kicked him, and clubbed him, unaware that an amateur photographer was recording the incident on videotape.

Kai Wright: You cannot overstate the emotion of this moment for Black people. It confirmed everything that people in the street have been saying about how cops were just showing up in our neighborhoods like a band of thugs, and especially the LAPD.

Christopher Johnson: Like an occupying force.

Kai Wright: Like an occupying force, and then they get away with it. Like, a year later, they get away with it. They're acquitted, and LA explodes.

KABC reporter: As the numbers swelled, they suddenly about a half hour ago just got more militant, and started burning things and started advancing. As I said-

Christopher Johnson: Then, not long after the LA riots, this big controversy erupts over a song. Not a rap song, but the fallout would have these big implications for conscious rap music.

Dan Charnas: In 1992, in the middle of the Presidential election, a police union publication in Dallas, Texas, a writer there, found a tape of Ice T's heavy metal group Body Count. Christopher Johnson: This is Ice T, the rap star from Los Angeles. He and a bunch of his friends had formed this metal band, and they put out a song called Cop Killer.

Kai Wright: Right.

[MUSIC- Ice T/Body Count: Cop Killer]

Christopher Johnson: Cop Killer mentions Rodney King. It mentions Daryl Gates, who was LA's police chief at the time. You remember this song?

Kai Wright: Very much.

Christopher Johnson: What do you remember about this song?

Kai Wright: This blew up the world. White people were angry.

Christopher Johnson: Especially cops.

Kai Wright: White people in general.

[MUSIC- Ice T/Body Count: Cop Killer]

Dan Charnas: This was a Warner Brothers/Time Warner product. The editor, writer, listens to this song, and writes a piece about it, transcribes the lyrics, and that leads to a nationwide outcry of how could Time Warner be encouraging this kind of violence against police.

Christopher Johnson: Dan says, because of Rodney King, police across the US were on the defensive.

Dan Charnas: This, they saw, as a chance to get the moral upper hand. It puts great pressure on the new chair of Time Warner to try to defend this, but very soon it became apparent that the Warner labels were going to be asked to provide a lot more oversight.

Christopher Johnson: Charnas says this had a real impact on rappers, and especially artists with political lyrics. That's because the rest of the industry is watching, and record labels in general start clamping down on songs that have these anti-policing messages.

Kai Wright: Yes, it’s just a reminder that you can’t commodify something and maintain some sort of political consciousness to it. These are just incompatible things.

Christopher Johnson: Exactly. We're talking about this time, I remember personally when popular rap music was making this shift to a sound that was almost this grotesque materialism. It was obsessed with money, and with stuff, but looking back at this era is important because it reminds us of how hip hop can influence the way the young Black people think about themselves as Black people.

I remember personally, for me, one of my favorite lines was from this Tribe Called Quest song. It's one of Q-Tip's lyrics where he says, "With speed, I'm agile, plus I'm worth your while. 100% intelligent Black child." Those kinds of ideas, man, that shaped us.

[music]

Kai Wright: They are among the many ways that over the past 50 years, hip hop has been shaping all of American culture. I'm Kai Wright, this is Notes From America. Happy Labor Day weekend, and maybe spend the rest of it bumping some Kool Moe Dee. Talk to you next week.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.