What's Driving the Rollback of Mask Mandates in Blue States

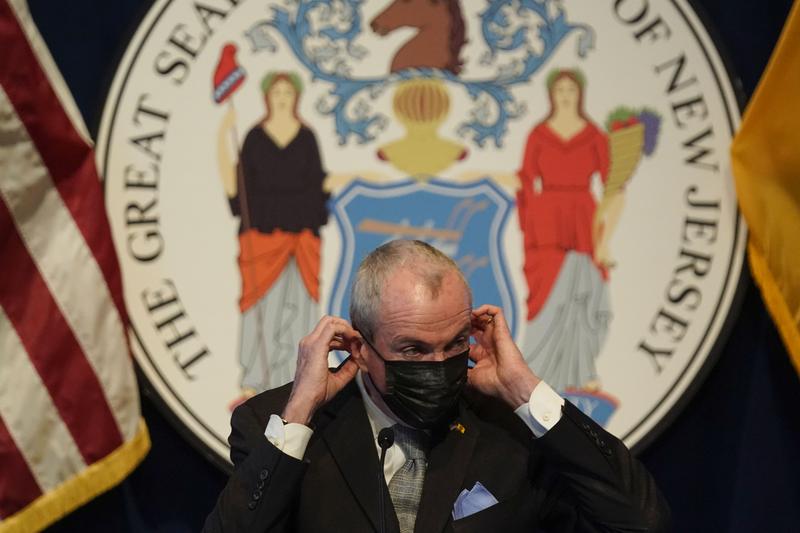

( Seth Wenig / AP Photo )

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: This is The Takeaway. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry.

Governor 1: There's no doubt about it that the peak is behind us. Now we're just off the peak. We still have very high levels of infection, but we're not out of the woods. Obviously, future surges are always possible. We really can't predict it with any high degree of certainty. We should just prepare and make sure that there are surges that we know how to handle.

Melissa Harris-Perry: All right, you heard it. It seems the surge in COVID-19 infections and deaths caused by the Omicron variant is declining. Cases have gone down by about 66% over the last two weeks and across the country rates and hospitalizations are declining. Although this is definitely welcome news, there is no evidence that this pandemic is drawing to a close. The peaks and surges of new variants have proved hard to predict. Nearly 2,500 people are still dying nationwide from COVID every day.

We can't forget the difficulty to wrap our minds around reality that nearly 925,000 Americans have already perished as a result of the coronavirus. When I look at these numbers, I keep wondering, did the pandemic have to be this bad? Certainly, no nation could have escaped fully such a deadly contagious disease, but here in the US, our response to COVID has been characterized by a political choice that likely made the pandemic even worse. Devolution.

Now, devolution is just an academic term for leaving it up to the states or to the localities. Just how much decision-making power should reside in the federal government versus state governments, that's been a matter of great disputes since our founding. Remember the articles of Confederation or the civil war, still, for most of the 20th century, Americans agreed that when the nation faced a truly great threat, a deadly existential crisis, that was when it was time for a unified response.

Think of how our entire nation responded following the attacks on Pearl Harbor, but when faced with the coronavirus, we didn't respond with one voice, we devolved. Handing over to governors, mayors, local school boards, and sometimes even to individual business owners the authority to make critical public health decisions.

Are the schools closed? Are masks required? Can you fill a restaurant to capacity? Is a vaccination card necessary to enter? For two years, the answer to these critical questions has been, it depends. The result is a confusing patchwork of public health guidelines and restrictions. Over the past few weeks, that patchwork has only gotten patchier.

Governor 2: We're not going to manage COVID to zero. We have to learn how to live with COVID.

Governor 3: At this time, we say that is the right decision to lift this mandate for indoor businesses and let counties, cities, and businesses to make their own decisions on what they want to do with respect to mask or the vaccination requirement.

Governor 4: If these trends continue and we expect them to, we will lift the indoor mask requirement.

Governor 5: Now is the appropriate time for me to announce that Nevada will rescind our mask mandate effective immediately.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Those are the voices who are among the nearly dozen governors who this month, including in the states of New York, California, and Illinois have announced an end to universal mask mandates, or simply allowed those mandates to expire. The latest round of mandate rollbacks seems to defy recommendations from the CDC.

Rochelle Walensky: Right now, our CDC guidance has not changed. We have and continue to recommend masking in areas of high and substantial transmission that is essentially everywhere in the country in public indoor settings. We continue to recommend universal masking in our schools.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Now that was CDC director, Rochelle Walensky speaking with Reuters earlier this month. Now here's what you told us about whether you still trust advice and guidance about COVID-19.

Laura Reed: I trust the national level public health officials like the CDC who follow and adapt to the science that presents itself. I don't trust my local county who would be recommending bloodletting and leaches if the politicians told them it would work. Laura Reed, Palisade Colorado.

Joe Wolfenden: My name is Joe Wolfenden. I'm calling from Sacramento, California. I take the advice of the public officials on COVID quite seriously. They're going on the advice of the experts which is the best knowledge we have as of this time. It's affecting my life. I have been following that advice. I live with nine people, including a couple of healthcare workers and they also follow that advice.

Caller: I was taking public advice seriously until the governor relaxed the mass mandate. I think that's just plum crazy.

Caller: I'm 80 years old, and I have never been gone for a whole bunch of vaccinations, frankly, but the consequences are so bad that it was a no-brainer, of course, I had to get all three shots.

Caller: Do I trust government officials about COVID-19? Right now I trust the government about as much as I trust gas station sushi. You've got to be kidding me.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Thanks to all of you who called in and shared your opinions with us. Here's the big question. In a patchwork of devolution, just how are we supposed to decide what to do next? Nsikan Akpan is Health and Science Editor at WNYC Newsroom. Nsikan, it's great to have you with us.

Nsikan Akpan: Always glad to be here.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Are the governors doing the right thing here by announcing these mask mandate rollbacks based on the science?

Nsikan Akpan: If you look at places like New York, New Jersey, or California cases are back to where they were before Omicron, or they're heading in the direction, or they're below it. New York is recording about 5,000 cases per day now. When governor Kathy Hochul reinstituted the mask mandate in early December, we were at like 10,000 cases per day. Huge improvement. If you look at the beginning of this year, 70,000 cases per day, we've seen a huge improvement, but we're also starting to see cases in hospitalizations and deaths plateau.

In New York City, cases are flattening out at about 2,000 per day, which is a lot. The number of people currently hospitalized, flattening out about 1,300 people per day, also a lot. We're still seeing about 100 deaths per day statewide in New York, and about 2,200 deaths per day nationwide. My worry right now and also the worry of some of the public health experts that I've spoken to is that severe cases and deaths could just keep petering along for weeks which would add up to a lot of harm over time.

Melissa Harris-Perry: When we're looking at those graphs and we're like, "Oh, it's coming down or it's plateauing," but what does that plateau mean if it's your grandfather or grandmother or you who is in that hospital?

Nsikan Akpan: Exactly. I think if you're in an at-risk group or if you're immunocompromised or if you're a child that's not vaccinated, the risk could still be high for you. We've seen a lot of pediatric COVID deaths, especially towards the tail end of last year. We saw way more deaths last year than we did during the first year of the pandemic when everything was locked down. I think the situation is improving, but there are certain groups that could face a lot of pain, like going forward if we don't make the right decisions right now.

Melissa Harris-Perry: You recently published an article drawing on research about mask efficacy, tell us a little bit about the science around masks.

Nsikan Akpan: Masks work. Studies show they can physically block airborne particles that cause infections. Studies on super spreader events show higher case rates in people who didn't wear masks versus those who did. That also includes studies on schools, but most of those studies are forensic investigations or retrospective, meaning they're looking back at something that happened.

The reason that we hear a certain group of people say there's no good science on mask-wearing is because researchers can't really conduct clinical trials on face covering. Subjects are picked at random and then they receive either a treatment or a placebo or no treatment. Because we know that mass provides some benefit, it would be unethical to withhold them from a placebo or control group. I spoke with Lawrence Kleinman, who's a pediatrician at Rutgers Wood Johnson Medical School in New Jersey. Here's what he said.

Lawrence Kleinman: In order to do a randomized control trial, one needs something called equipoise. That is two options for which there is truly no evidence that one is better than the other.

Nsikan Akpan: Yes. The closest thing that we have to a clinical trial is this Science Magazine report that involved about 342,000 adults in Bangladesh. What they did was they gave masks to everybody, so you didn't have this ethical dilemma, but a subset were also given educational outreach or polite reminders from paid locals called mask promoters. In villages without the reinforcement, only 13% of people wore face coverings, mask-wearing rose to 42% in places with those extra nudges which corresponded with 11% drop in COVID rates.

Melissa Harris-Perry: You just used the word extra nudge. Of course, pointing there to the behavioral economics around nudges and sludge, I guess not sludges, but around the nudge and the sludge. When we're talking about devolution here, the idea that localities and states have been able to make these decisions, we introduced an enormous amount of sludge in the system. What if from the beginning, or even now, there was one univocal national perspective that says "masks, masks, everybody, masks"?

Nsikan Akpan: Typically, during a crisis like this, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, they would be the unified voice. They would be the people that we go to for advice and for information. I think during the first year of the pandemic, they largely abdicated that role. What you saw was you had a lot of expert voices say on Twitter or in the news giving their opinions like they were trying to help out the situation but I think what happens sometimes is that it can create uncertainty when those experts disagree.

You get a situation then when people don’t really know what to do and it can lead to a lot of fatigue. I think some of that fatigue has created political pressure on some of these Democratic governors. There's obviously the conservative-leaning camp, which has been pushing to rollback precautions for a very long time but for my story, I talked to Dr. Jay van Beville, who's a social psychologist and neuroscientist at New York University who studies how partisanship influences the way people think. He said people who've been following the rules are also pushing for changes.

Dr. Jay van Beville: There's people who've been against COVID being a real problem, aren't going to change probably. At this point, I don't think they're going to change. That hard group is very hardcore. Then what you're going to get is a bigger group of people who are not left or right. They could be all over the political spectrum who have been boosted and done these things and we're two years in and they want a slow phase-in or a quick phase-in to normality.

Nsikan Akpan: Democratic governors were left in a situation where even their loyal constituents weren't going to follow their policies. I think people who had been following the rules, who have been vaccinated, who have been boosted, who haven't been going to work, haven't been going to see Spiderman in the movie theaters. I think they were just like-- they're just getting to a point where they're fed up. Even before Governor Hochul's announcement, more and more people in New York City were ditching masks in public. The policy was losing value and that can turn into a pretty big erosion of power.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Nsikan, let's take a really quick break right here. We're going to have more on the rollback of mask mandates in blue states and the science around this in just one moment.

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: Back with you now on The Takeaway, I'm Melissa Harris-Perry, and still with me is Nsikan Akpan, Health and Science Editor for the WNYC Newsroom. Nsikan, say a little bit more about children and especially obviously the under-five population, not only the unvaccinated, they're not even eligible for vaccination.

Nsikan Akpan: Obviously, with Pfizer, everyone was expecting this decision to come through earlier this month. They had to push it back because Pfizer wants to get more data before they conduct the official review with the Food and Drug Administration for that emergency authorization for vaccines for people under five, six months to five. I think that that was disappointing for a lot of parents who want to vaccinate their kids and have them protected but to be honest, the vaccination for kids, especially among kids 5 to 11 has been going very slowly. Nationally, five to elevens are only 24% fully vaccinated. It's only about a quarter of them.

Even if you go up to the teenagers, 12 to 17s, it's only about 56% fully vaccinated, so about half are not vaccinated or only have one shot. New York, it's about 40% fully vaccinated. What we're seeing in national surveys like one's done by the Kaiser Family Foundation is that there's actually a fair amount of hesitancy, like only 3 in 10 parents say they're going to get their child under the age of five vaccinated.

Then when you look at groups like the 5s to 11s and what their parents' are saying, only about like 50% of those parents are saying like, "Oh, we're going to wait and see still?" "In January, we're waiting and see, or we're not going to get our kids, 5 to 11, vaccinated."

We're inside of this weird position where I think if you open up the vaccinations for kids, like we've done, and if you open it up for people under five, some parents are going to do it, but some parents just aren't, and so then it's like, "Okay, how do we protect those kids that are unvaccinated? Do we try to push for more vaccinations in adults?" I think if we did that, there is a chance you could also bring down the transmission to kids and therefore the case rates in kids, or do you keep using masks? Do you keep using social distancing in schools or in other public places to protect the kids?

Melissa Harris-Perry: It may be that we find ourselves in this moment of experimentation. You talked about the gold standard for experimentation for clinical trials, requiring that the alternative, the placebo effect be something that we don't have evidence for. That it would be helpful. There's no placebo for non-mask wearying. We know that it reduces transmission, but with governors now opening up and allowing far more public places to go unmasked or partially masked, we may be in a place where whether or not it would be ethical at a clinical trial or not, it's going to start happening as a matter of public policy.

From the folks that you've talked to, is there a sense of what we should be watching in terms of numbers, in terms of transmissions to understand how this experiment, one which we may not have opted into, but nonetheless find ourselves in, how it's going and when to make a different decision if necessary?

Nsikan Akpan: Yes, I think we should look for plateaus. If we see cases in hospitalizations and deaths plateau in the thousands, I think that can tell you that we're still getting a lot of community transmission, that Omicron hasn't reached everybody and it's just slowly winding its way through the population.

Then I think if that happens, if you have this long plateau, this extension, you're going to get to a point with this wave where its total number of deaths or hospitalizations is going to outnumber the total numbers of deaths and hospitalizations that we've seen in past waves that we thought were really, really bad. I think when you reach that point something will click and people will be like, "Oh, hey, we've just pushed this to the backgrounds. We're not thinking about it, but actually, the situation is really bad."

Melissa Harris-Perry: I'm fascinated by your political point about if people don't follow the rules that you set, that is an erosion of power and so you have to act. Part of it is actually moving your rules so it doesn't look like you are in a situation of people ignoring you. Is that what's going on here with governors or have governors decided that they're buying the narrative that there's an economic effect to masking. I'm really trying to understand what the core political, or power-based reason is that particularly Democratic governors are making this choice.

Nsikan Akpan: I think there's a political calculus going on right now over the tradeoffs between masks and vaccines. I think a year ago, a lot of these governors said, "Hey if you go get vaccinated, you can take off these masks, we're making a deal with you. We're making a bargain with you." It pitted mass versus vaccines.

I think they're like, "Well, okay, now we need to make good on that promise." Even though a lot of public health experts were like, "We need to layer on protection in order to lower the risk as much as we can." There's this thing called the Swiss cheese model of COVID health precautions, where it's like, you layer on vaccination, you layer on mass, you layer on social distancing. By doing that, you prevent the coronavirus for squeezing through society.

I think yes, governors want to make good on that promise, but I think there's also the danger of like once you remove a precaution, say cases go back up, say another new variant emerges, can you then tell people to put masks back on? Are they going to listen to you then? I wonder if that's the calculus that the CDC is making or the federal government is making that the cases are still high. If we take this off now and it pivots, will people listen to us going forward? I just think that's another thing that politicians should probably keep in mind as we continue to move through COVID-19.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Nsikan Akpan is the Health and Science Editor for the WNYC Newsroom. Thanks so much, Nsikan.

Nsikan Akpan: Of course, thanks for having me.

Melissa Harris-Perry: This is The Takeaway with Melissa Harris-Perry.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.