What A Segregated Mental Asylum Can Tell Us About Health Care in the US Today

Suzanne Gaber (show producer): What have your discussions with your family been like around mental health?

Female Speaker 2: Typical African American. You always heard the not crazy, I'm going to say crazy, uncle or aunt that that's just the way they were.

Female Speaker 3: It's always kind of a hush-hush, we don't talk about it.

Female Speaker 4: I think it's a difficult balancing act. I would say within my immediate family it's not stigmatized.

Female Speaker 5: I feel like it's changed recently. There's more talk about mental health on social media, and among friends, peers.

Female Speaker 2: I know some folks that go to therapy. You don't tell everybody you're going to therapy.

Female Speaker 3: It's less of a curse word. It's less of a we don't talk about it. I think we are able to name the thing, but now we're starting to have to engage with the memories and things that have happened, and now that's a little scary.

[music]

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America, I'm Kai Wright. Welcome to the show. Engaging with memories that we've tried to avoid or push down is indeed scary, but as someone who will happily tell you that I'm in therapy, I also know that reckoning with scary stuff often leads to healing. This week we're going to engage with some scary memories in our nation's collective past. Memories around mental health care and abuse. We're going to look at one place in particular, a small town in Maryland that shaped a lot about how we address mental health in this country.

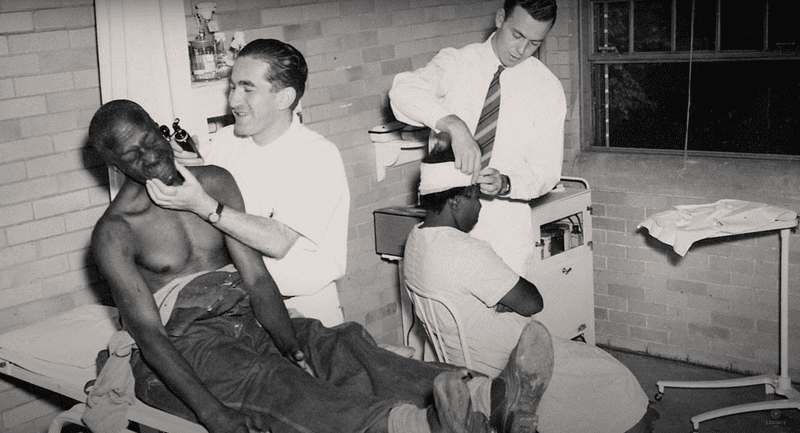

The story begins in 1911 when 12 men were brought into the woods outside of Baltimore and told to start working. They were tasked with creating one of the first asylums for Black Americans with mental illnesses. It was a segregated facility called Maryland’s Hospital for the Negro Insane. The workers who built it, they would soon become its first patients. The hospital would remain open for 93 years, eventually renamed the Crownsville Hospital Center. It would change the community that lived around it, and today 20 years after its closing, its impact is still being felt, and not only by people in Crownsville, Maryland.

Journalist Antonia Hylton has spent 10 years learning about this institution, and she tells its story in her new book Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum. She joins me now to dig into the history and to explore what it teaches us about mental health in this country. Antonia, welcome to the show.

Antonia Hylton: Thanks for having me, Kai.

Kai Wright: Let's start with that striking story about this institution's origins. The hospital itself was built by the patients which was an unheard of practice at the time. Can you tell me that story? Who were the 12 men who were tasked with this?

Antonia Hylton: Well, we don't know their names. We know some of the names of men who were present in 1911 and 1912 at Crownsville, but we don't know exactly who the first 12 were. Their status as these nameless people who were transferred from another all-white hospital called Spring Grove, where they were no longer welcomed, and then brought here into the middle of a forest in what-- For people who are in Maryland what they would know as Bacon Ridge Natural Area, but at the time would've been this completely thick empty forest.

They are marched in there on a very cold day, March 13th, 1911, by a doctor and a number of officials in the state of Maryland, who bring them not to a hospital ward, not even to a house. They're brought right into the middle of this forest and they have to start cutting down trees, clearing paths. They have to also harvest willow plant, and they have to create baskets and all of these goods that the hospital is preparing to use to offset the cost of the construction and care. They begin to do the back-breaking work of building an asylum that is still standing, mind you, more than a century later.

You can drive down Crownsville Road in Maryland and look at the work of these 12 men. That group of 12, they are the first people there for the first few weeks, but week after week the hospital's bringing in new Black men and boys as young as 10 and 12 years old, to what is becoming a work colony, a plantation of sorts.

Kai Wright: Why were these 12 men tasked with building the place in the first place? Was it just like, this is free labor? What was the justification for that?

Antonia Hylton: Well, the state of Maryland had been debating for years what to do about what they called rising insanity among Black people. Many of them, and not just in Maryland, all around the United States at the time, in the decades after emancipation, white doctors and politicians would debate what they thought was going on with Black people's bodies and minds. They believed many of them were suffering after emancipation. Very few of them considered the role that enslavement might have played in mental suffering.

They often thought, well emancipation had been a mistake. They miss the plantation structure. They miss the good old days. That is the natural state of being for Black people. When they decided that they needed to do something about this insanity among Black Marylanders. They realized that they wanted to build this institution because they believed Black people to be so different from white Marylanders, it needed to be in a different place, but they didn't want to pay for it.

Conveniently all these men know how to build. They have these skills. Many of them had come off of different farms and agricultural work around the state of Maryland so they already know what to do. The state takes advantage of that aggressively and week after week brings in dozens more men. It takes them three seasons to build the original iconic structures that are still standing to this day. Something that no other patient in the state of Maryland of any other racial background was ever forced to do. At least in my research, I've not been able to find an asylum anywhere else in the country that started this way.

Kai Wright: On this idea that they were insane because they were free and Black, there was an actual mental health diagnosis at the time, right?

Antonia Hylton: Yes.

Kai Wright: It's been called Drapetomania-

Antonia Hylton: That's right.

Kai Wright: -going back. Tell us what Drapetomania was.

Antonia Hylton: A term coined by a man named Samuel Cartwright, a physician in the South. He was not alone in creating these pseudo-scientific terms in trying to using science and medicine make sense of or protect, really, the racial order of the United States in the 19th century all the way up to the early 20th century. He creates this term, and what Drapetomania is in his view, is a disease, a sickness that overcomes Black people who defy their master's orders. Who run away from plantations and become free. He describes Black people's state of being when they do that as indolent, childish, very prone to alcoholism. Essentially their minds, he's saying, unravel the moment they don't have the direction, the order, and the control of a benevolent white master.

He would publish these papers, and write letters, and argue with other physicians not just because he wanted to put his beliefs about Black people out there, but actually because he was trying to send a message to slave owners. A sort of an economic message really to people running these plantations at the time, that you need to very aggressively beat back any kind of resistance on your plantation. He encouraged beatings and very physical forms of violence back against slaves at the time, as a form of mental illness prevention. As a sort of therapy, if you can believe it.

Kai Wright: This idea was still part of the supposed science of mental health in the early 1900s when Crownsville was built. Is it also the case at that time there was also this broader idea, no one else had to build their own mental health facilities, but this notion that labor was somehow curative of mental illness was a broader idea outside of the racism of this case as well, right?

Antonia Hylton: That's right.

Kai Wright: Can you talk about that a little bit? Help us understand that moment.

Antonia Hylton: That had long been the case. This idea that, in Europe and in the United States, is these institutions were initially built that patients shouldn't be idle. They shouldn't be sitting around in rooms all day, or sleeping all day, they should go outside, they should work in gardens. Then eventually they started to follow the United States and European model of industrial therapy. The idea is you would get patients working in a laundry or in a carpentry shop. They would maybe be somebody's apprentice while staying at the hospital. The goal was that they would work their way up, develop a trade, a skill. Then when they recovered, they would have references. They would have a community, a real background, a resume of sorts to go into a field and begin their life anew.

When you look at the records for Crownsville though, that intention to build a career, to reconnect people to a broader community, is lacking. There aren't these sort of internships and apprentice opportunities. There is a heavy, heavy emphasis on the antebellum plantation structure. The hospital records show this, an extreme attention to the cost savings to the government, the amount they can make from selling products, the way in which the patients are producing their own food. The state is, in other words, not spending money to feed the patients themselves. In addition to doing all that labor during the day, when they come back inside, they also are serving the superintendent, who's the head.

Kai Wright: The white staff.

Antonia Hylton: The white staff. They're serving them meals. You would think in a place like this, because that would've been the case at other institutions, it would've been the other way around. At this time, you have to remember, during Jim Crow, this belief that Black people are so different and so much less human than anyone else has infected everything, including the clinical setting. This recreation of the plantation is in their minds, what good therapy, what the natural order of things is. That's why you see, yes, there's work across the board for all patients, and that work could be abusive for patients of all backgrounds, but the emphasis on agricultural labor, they start renting Crownsville patients out to nearby private businesses.

Kai Wright: The same thing is happening in corrections at the time, correct? That they're arresting Black people for being idle and then renting them out-

Antonia Hylton: That's right.

Kai Wright: -to idle plantations in a recreation of slavery. That same thing is happening in the mental health space.

Antonia Hylton: In the mental health space, in the correction space, in the reformatory space. During that period in the early 20th century, there are all these schools for boys and girls who have misbehaved, or gotten in trouble with their families or have become orphans. Similarly, those institutions for Black boys typically end up feeding into that same system as well.

Kai Wright: I'm midway through Tananarive Due's latest mystery, The Reformatory, about the ghost of just that, and it's chilling. We need to take a break. I'm Kai Wright, and this is Notes from America. I'm talking with NBC News correspondent Antonia Hylton about her new book, Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum. Coming up, we're going to add your voices to the conversation. You can call or send us a text message if you've got a question about the history of Crownsville Hospital, or maybe a personal experience with mental health in your family that you'd like to share. I'm particularly curious if we have anyone listening who had family at Crownsville or another segregated institution like that, more just ahead.

[music]

Regina deHeer (show producer): Hi, I'm Regina, a producer here at Notes from America with Kai Wright. I know you're loving this episode. I promise I won't hold you long, but I have to ask, have you seen what we're up to on Instagram? That's where we post questions to you that help shape the conversations that we have on this podcast. Plus, it's a great way to keep up with the show. Follow Notes with Kai on Instagram, that's @noteswithkai, and we'll talk to you there. Thanks for listening.

[music]

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright, and I'm talking with Journalist Antonia Hylton about her new book. It's called Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum. We can also talk about her work covering mental health in this country generally, and we can take your calls and texts if you've got a question about the history Antonia describes or the ways in which racism and other biases have shaped our understanding of mental health. Talk to us.

Antonia, your own family history with mental illness and the silences around it was one of your provocations in doing this research. Can you introduce us to your father's cousin Maynard? He was this wonderful young man in your family. What was he like? What was his personality like in your family?

Antonia Hylton: Maynard was this beautiful, hilarious, athletic, belligerent presence in my family. I come from a very big Black family, and so to stand out-

Kai Wright: Such a joy.

Antonia Hylton: -that's something. Yes, it takes a lot of personality, actually. He loved poetry. He read all kinds of philosophy. He was a huge fan of Malcolm X and carried around an autographed copy of his autobiography until he then decided to hand it down to his little brother, Kendall, who is my dad's cousin, but I consider him an uncle. He was really a mentor too to a lot of the other young men in my dad's generation. He taught them a lot of their first swear words. He would help my dad and his twin brother and his older brother. They would get into joking boxing matches. At dinner time, he would drink with my grandparents and argue about Richard Nixon and all-- He liked to call it his theories of the world order. He was someone who was so alive, so interested in politics and civil rights and in being Black in America.

As he got older, it was really hard for people in the '60s and '70s in my family to see this, but he started becoming more conspiratorial. Started sleeping less and less. They didn't know it at the time, but he had schizophrenia. He was hearing voices. The problem was, and this is what I hear from my father and from my uncle Kendall, and others who were around at the time, the paranoia, fear in that period in America was commonplace for Black people.

At one point he visits my father in the '70s. My dad is just about 11 years old. My dad grew up with the riots in Detroit. This fear of persecution, rejection from the system, concern that the man was after you, it was pretty normal. It's hard to diagnose mental illness in those circumstances. It's not until Maynard is killed by a police officer back in his home state of Alabama on the steps of a federal building in Mobile that my family really is faced with what Maynard has been dealing with all along.

Kai Wright: What happened to Maynard in that incident?

Antonia Hylton: Really, all we know about what happened to Maynard that day comes from the Mobile, Alabama Police Department. There are no witnesses in our family, no family friends who were there at the federal building downtown. What we know from their version of events is that Maynard arrived in distress begging someone to take him out of the country, fearful for his life and wanting to get out of the United States as fast as possible. He encounters a guard. That guard runs inside. It turns out Maynard has a gun on him. A white police officer arrives on the scene, and within seconds of finding Maynard, alleges that Maynard runs at him with the gun and he shoots him in the abdomen, and kills him.

It is a death that is so traumatizing and so strange for my family that when it happens in the '70s, it becomes impossible for generations of my family to figure out how to talk about Maynard for the rest of time. His death changes my father. It changes his brother Kendall. A year later, Maynard's dad, who was his senior, Maynard was his namesake, passes away and everyone in the family believes it's from heartbreak. All that loss in such a short period of time, my family really starts to pick up this habit of deciding not talking about mental illness, not addressing Maynard's life. They hide photographs of Maynard. His photos are taken down from mantles.

By the time I was born, I knew his name, but I'd never seen his face. I knew his death, but I didn't know a thing about his life. I'm one of seven kids. For me and my six siblings growing up, we had a lot of anger about how little some of the older generations in our family wanted to talk about these things. Many of us experienced depression and anxiety growing up, and we would try to talk about these things or try to know if someone else had gone through it and we couldn't get answers.

At first, I was really angry with my family, and Maynard came to symbolize that anger. Then, when I came to understand this history, both the fullness of Maynard's life, but also this broader history that, for me, Crownsville has come to represent, I had a lot more patience and compassion for them because I see how Black families come to sense that they're not safe in these spaces, that there either is no care available to them or if there is care that it can be harmful. In those circumstances, what is there to talk about? What is there to do? How do you help? Who can you call?

I see their actions now as a defense mechanism or a strange way of thinking that they could protect us, but all they really did do was make us all so much more curious. I felt like I had to know who Maynard was. I missed this person who I never got the chance to meet because I could see how much he had clearly affected my father, and my uncles, and my grandparents.

One of the things I do in the book, in addition to telling the story of Crownsville Hospital, is share some of my family's experiences with the mental healthcare system in America. I share more of Maynard's life because I think part of I guess the driving force behind all this for me is this feeling that we shouldn't hide our family members who've suffered. We shouldn't take their photos down. They shouldn't be a footnote in our family history. They deserve to be out front. Their stories need to be told. Actually, if we talk about them more and we love on them a little bit harder, all of us will be better for it and maybe our system will be better.

Kai Wright: There's so many of us with similar stories. Let's go to Hannah in Mound, Minnesota who has a question? Hannah, welcome to the show.

Hannah: Yes. Hi. Thank you so much for taking my call. I just really wanted to draw a line, and I don't know necessarily if I can articulate it in the best way as a question, but when you tell people about the institution of slavery, and then you're talking about institutionalizing people post-slavery based mostly on color, and then you correlate it to the current prison system, which again, isn't incarcerating people of color on the high level. Well, some prisons are built actually on the sites of past plantations. That these people are put into the same situations that we're looking at in the story that I think it's just perpetuating over time with different veils and that it's the same thing. It's like you're taking a person and you are dehumanizing them on a basis, and then you're institutionalizing them for the benefit of a different society. It really is the perpetuation of slavery.

Kai Wright: I'm going to stop you there, Hannah, and thank you for that tie. In the book, Antonia, you, in fact, talk about a lot of these interconnected perpetuation that Hannah's talking about through actual individual families. One of them I want to ask you about, which is really striking, is that the daughter of Henrietta Lacks was a patient at Crownsville. The quick backstory, Henrietta Lacks was a Black woman who had cervical cancer and doctors harvested her cells without her consent. Those cells have been the basis for huge amounts of medical research including the development of a polio vaccine but her family never knew about it for decades. It turns out that Henrietta's daughter, Elise, was at Crownsville. What can you tell me about Elise and why her story is an important example of this intergenerational question?

Antonia Hylton: Well, for me, there's a direct parallel between Henrietta Lacks and her daughter Elsie, who is just a child.

Kai Wright: Elsie, sorry.

Antonia Hylton: Yes. Elsie goes to Crownsville around the same time that Henrietta's health is declining. Henrietta and her family are struggling to care for her daughter because she has been born with what they called idiocy at the time. She's unable to speak. She mostly communicates through cries and physical signs. Henrietta and her have this very special bond, but Henrietta becomes overwhelmed and as many people did at that time, needed to send this child somewhere. They bring her to Crownsville, the only place that would accept Black people suffering with any of these kinds of developmental, cognitive, behavioral, emotional differences.

Elsie ends up subjected to experimentation and to abuse by science in a different way at the very moment that her mom is having her cells taken from her. Elsie is subjected to a really gruesome procedure in which staff at the hospital drill into her skull and several other, or many other, dozens of other patients who are just like Elsie. They pump the skull full of air and helium. They want to get a look at people who have a condition called epilepsy or what they thought was epilepsy at the time. These experiments, the drilling through the patient's brains, they don't even publish anything that we can find in the record that leads to any new discovery, any new therapy for the patients there. About a hundred children like Elsie are subjected to this. Elsie ends up dying at 15 with extreme complications from all of this.

For me, what I was so struck by with Elsie's story, which was first reported by Rebecca Skloot in all of her reporting on Henrietta's family. I think often people think about Henrietta Lacks and the billion-dollar cells, you think about the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, these big flashy moments, or a single person. When you see that this happened twice to just one family, you're actually-- I think Elsie's story calls on us to consider the fact that this was happening in a lot of small, quiet, and different ways in facilities all around our country. That very likely these things have contributed to a current reality in which these very same communities have very fraught relationships with institutions like Johns Hopkins or mental health care facilities all over the country really. You see it happen twice just to this one family. I've met Henrietta's descendants, they're still angry at the medical systems in Baltimore and Annapolis more broadly.

Kai Wright: Indeed, I would hope so.

Antonia Hylton: They are. Every single one of these moments, whether they've been reported or published or not, they have led to a domino effect and a disconnection and an isolation and exploitation of communities like ours. That's why I give Elsie's story the space that I do in the book because I think it's important for us to see this is so much bigger than some of the major incidents or stories we often recognize or we think we can just pay people back for one, but the pain goes a lot deeper than that.

Kai Wright: I hope we have time before we take a break. I want to ask you to read a poem from the book because it gives us a little sense of what we're talking about for the patients. It was written in 1952 by a man named Mr. New Unit.

Antonia Hylton: Yes. That's a pseudonym. Many of the patients at Crownsville would write poetry and publish them in weekly newsletters or just write them on the wall, and they would use pseudonyms. Mr. New Unit wrote this poem in April 1952 at a time when the asylum was still 100% Black. He wrote,

If you get sick against your will, they will bring you to Crownsville

If you're lucky so and so, it won't be long before you go

The doctors keep you until, and there you'll stay in Crownsville

If they don't make up their mind, you'll stay there for a long, long time

When it's time for you to go, you and everybody will know, and your mission, you'll fulfill, then you can leave Crownsville

Someday in the Sweet by and by, you won't have to stay there until you die

Just trust in God and you can depend, He will bring things to an end

Kai Wright: That is quite affecting. It points to the question of how often did patients actually leave the facility.

Antonia Hylton: During the first half of the 20th century, you were more likely to die in Crownsville than to get out. Sometimes you would look at records for one year and just 12 people of the thousands were able to get reconnected to their families or communities. In that same year, maybe a hundred or so people would perish there. I think that this poem reflects the hopelessness, the isolation of that time. When I found it, it was really amazing to me because one of the things that was so frustrating while doing this reporting was that prior to about 1955 they are almost no patient voices. The majority of the staff in this period they're really all white. They're systematically barring Black people from being able to work as nurses and doctors in the institution at that time.

In their notes are not putting patients' perspectives, stories, personal memories. They're not making much of an effort to call their families or to integrate families into care. It's not until about 1955 and into the 60s as more and more Black people get their very first jobs there, that those things start to shift. Not because a new medication arrives on the ward, not because there's new technology really. Although some of that does start to arrive, what really starts to shift a lot of the relationship and your access to patient perspectives is simply that there were Black people there who knew them, who literally rode the bus to school with them. Who then start saying, "Oh, we have to do something about this."

Kai Wright: My guest is Antonia Hylton, author of Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum. Up next, we'll hear from you about the discussion of mental health and mental illness, how it unfolds in your families. If you've got a question for Antonia, again, you can text us or call us. I'm Kai Wright. Stay with us. This is Notes from America.

[music]

Kai Wright: This is Notes From America. I'm Kai Wright. Before we get back to our conversation, a quick note about next week's show. The countdown to election day 2024 is on, and we're going to be checking in with different kinds of voters or not voters about what their priorities are this year. First up, we want to hear from people in our audience who consider themselves conservative, whatever that means to you. In particular, we want to hear from conservatives for whom Donald Trump is decidedly not a candidate you can get behind.

We want to know what's on your minds now that he's poised to be the Republican nominee, and where you are planning to put your political energy this year. The best way to talk to us is record a voice memo on your phone and email it to us at notes@wnyc.org. Right now, we are spending time with Antonia Hylton, author of Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum. We can take your calls and questions for her about the history that she has covered here. Let's go to Pascale in Jericho, New York. Pascale, welcome to the show.

Pascale: Hi, Kai. Thank you so much for taking my call and covering this such an important talk topic with this author, Ms. Hylton. I'm a child and adolescent psychiatrist, and I'm teaching medical students. I literally just had a talk about racism and psychiatry, and we talked exactly about this topic, about how our country has really had a history of racialized social control that's reinvented itself to meet the dominant social class according to the constraints of every era. Just going back to the Jim Crow era, I talked specifically about the central lunatic asylum in Virginia where Blacks would be thrown in there for not getting off the sidewalks if they didn't let a white person pass. Things like talking back to a boss and the like.

The treatment was really, as you had mentioned, putting them into hard labor that mimicked slavery at the time. It's no wonder that Blacks mistrust the mental health system and we're seeing the repercussions today. That's what I was telling my students that there's a lack of Black psychiatrists. There still continues to be diagnostic biases, and the mental health payment structure really excludes people who can't afford to pay out of pocket. Thank you, Ms. Hylton, for your book. I can't wait to get it. My students actually came up to me and showed me the book.

Kai Wright: Oh, there you go. Good student.

Pascale: So important. Even as a Black woman in psychiatry, we have to face this history so that we don't repeat any of this and be vigilant not just in psychiatry, but in all fields of medicine. Thank you so, so much.

Kai Wright: Thank you, Pascale. That points to a lot of what you talk about in the book when the Black staff did finally arrive. There's one story in your book that I think really shows the difference that it made. You tell the story of a man named Mr. Bell who was in Crownsville for decades until a Black nurse comes into the facility and starts spending time with him. Can you tell us what happens to him after that?

Antonia Hylton: Oh, boy. This is a story that I think about all the time. Mr. Bell is on an overcrowded, underfunded ward packed with hundreds of men on a floor in Crownsville. One week in 1955, a woman named Marie Goff gets her first job there and is told she's assigned to this ward. Marie is about five feet tall, maybe a hundred pounds soaking wet. She and a few other women are assigned as some of the first Black women underneath white supervisors on the ward. She goes in and she starts to see how filthy, how terrible everything is. She starts to politely try to push her supervisor to let her bring some of the patients outside. She brings this gentleman, Mr. Bell, along with another group of patients outside after a few weeks of fighting on their behalf. He tells her he hasn't seen the sun or the sky in years.

She just becomes curious about him. She digs into his history and discovers that the only reason that he was brought to Crownsville is because her supervisor in coordination with authorities in Baltimore had overheard him speaking and he has a British accent, and they had never heard a Black person with a British accent. They thought he just made it up. They pick him up. He's brought to Crownsville and he is there for years. It turns out once Marie gets to know Mr. Bell that he was born in London, he was a jockey, came to America, and fell on some hard times, but he had never made that accent up and he had no actual mental health diagnosis. She's exactly right. These institutions became receptacles for Black Americans, seen as strange as unwelcome as just not fitting into the broader status quo.

I also tell the story at one point of a researcher who comes to work at Crownsville, one of the psychiatric departments where they're really looking at patient files, but not working closely with the patients themselves. She freaks out when she discovers a record of a patient who's brought there for the crime of cutting off a white woman who's on a horse in traffic on the street. That patient too had been at Crownsville for a very, very long time.

One of my favorite parts of the reporting is, a lot of these women who came in and started to change the culture, who started to ask the questions, they arrived and it was not rocket science. They really start just with their kindness, their willingness to listen, to pick up the phone, and try to reach a family member or a loved one. They start to change patient outcomes, get people out of Crownsville for the first time and back home.

They also start treating their own friends and neighbors that they grew up with and giving them this sort of extra level of love. They wrap their arms around the people that they know there and commit themselves to a form of community mental health care that at one point our country thought we would really build but never came to be. In this strange moment, this place that has this sorted history comes to actually represent a community finally taking care of itself for a short period of time. It's those women, majority of them women but also men, who make all the difference.

Kai Wright: It's interesting too because the place was open until 2004 for--

Antonia Hylton: Within our lifetimes. Very much within our lifetime.

Kai Wright: There are many living people for you to talk to, and you talk to staff members and some don't believe that it should have been closed. Tell me about that. I think there was one nurse in particular, Joyce Philip, who said--

Antonia Hylton: Joyce Philip, Faye Belt doesn't feel like Crownsville should have closed. That's not because they believe that these institutions were perfect, shouldn't have been reformed and altered in a significant way, but their concern is that what we've left ourselves with is worse. What they tell me is they drive around and I got to ride around with them and see Annapolis and Baltimore through their eyes. Their patients are living under overpasses out on the street. Some of them are in group homes if they are lucky, but those group homes often mistreat them. Many of them have passed away, and then many of them have ended up in prison and in jail.

I think the other piece of this that breaks their hearts is that they put in all this effort in the 60s, 70s, 80s, after these medications arrive, they're able to try to do trauma-informed care. They're bringing more talk therapists onto the wards. Black women and men are treating Black women and men and it's really a community hospital for the first time. Just at that moment where they're starting to build a community hospital, the state starts chipping away at funding, rolling back support for mental healthcare services and constructing new juvenile facilities, new prisons, and jails around the state of Maryland. That's really where their institutional focus shifts.

These Black doctors come to feel like, "We fought and fought and fought for integration. We fought to come in here and to have access to this space. At the very moment we win now they want our people to end up somewhere else." There's that anger at what could have been. I think there's that outrage at what we all I think around this country can see we've been left with, which is a mental healthcare system that's really in tatters that even the wealthy have anger and concern about. You can have great insurance and be waiting for six months on a waitlist to get to see a certain doctor or to get a bed in an inpatient treatment facility. If you don't have great insurance, well, you're just out of luck.

Kai Wright: This is a much larger question than you have time to answer for, but how did we end up there? Where is the pivotal point that we end up there? Is this in fact, the closure of mental health institutions in the early 80s that some may have heard of? Where in your mind is the pivotal point that brings us there?

Antonia Hylton: A lot of people argue about this. I think my personal pivotal point is actually in the '60s during the Civil Rights movement because there are a few things going on in that moment that I think are not properly understood there. These different movements concurrently happening there. On the one hand, we have a community, a culture, that is becoming more sympathetic toward patients. Medications are arriving and there's a push, a drive, get them out of the hospitals back to the community, we want patients home. At the very same time, the civil rights movement is happening. There's unprecedented levels of protests. Police are responding and brutally beating people in the streets. Black men are being carted off to jail or their protests being criminalized and pathologized in some ways.

At the very moment where our society says it has become more compassionate to people with mental illness, it's become very uncomfortable with and very reactive to Black protest and Black criticism of this country. That means that as the hospital deinstitutionalizes, but we build more prisons and jails. There's a major shift happening and Black people are right at the center of that shift. Decisions our country starts to make about who is sick and who is criminal, who deserves care and who deserves incarceration, who do we think can be redeemed, fixed, rehabilitated, and who is a lost cause. For me, those conversations start in the '60s. A lot of times people want to say Reagan shows up and he ruins everything. It's not quite right.

Kai Wright: It's not Ronald Reagan. It goes before that.

Antonia Hylton: No. Unfortunately, he helped lower the system into the grave and close the casket and all that, but it starts unraveling a lot sooner.

Kai Wright: We have a caller from Baltimore who asks, "Do you know what happened to the Advocate Sharon Jones, her relative was in Crownsville and she fought for better care." Are you familiar with the Advocate Sharon Jones?

Antonia Hylton: I'm not off the top of my head familiar with her. I can tell you if you are listening and you know somebody who has a connection to Crownsville, that there are teams of people. There is a local historian named Janice Hayes-Williams, who has done a lot to catalog former patients there, particularly if you have loved ones who've passed away. She has compiled a binder, which I actually have in front of me here with the names of people who were buried on site.

We also have records for people who were sent as cadavers to medical institutions around the state of Maryland. There are living nurses who have a lot of memories of patients who they worked with. Some of this you can have an easier time finding that connection through community than you can if you honestly go through some of the bureaucratic red tape of the state and local government.

Kai Wright: Another question, sort of like this, somebody's text message asks, "Was San Quentin's gas chamber built by inmates as well? That they were under the impression that that was true."

Antonia Hylton: That may be true. I would want to double-check that. [laughs]

Kai Wright: You can't be the source of facts for that.

Antonia Hylton: I don't want to be the source of that.

Kai Wright: Got you. Speaking of all of these connections, one more thing I want to ask you about that's connected is, you've talked about Jordan Neely. This was the young man who was killed on the New York City subway in last spring in what appeared to be a mental health crisis. You covered that story and you see through lines between that and what happened to your father's cousin Maynard and the story you tell in Crownsville. Can you just connect the history to Jordan Neely's story?

Antonia Hylton: Yes. I try to bring you to the present day and to Jordan Neely so that people can see how each era of our mental healthcare system has built upon the one that came before it. I see there were so many similarities between my cousin Maynard and Jordan Neely. They're pretty close in age 27 and 30. They're both experiencing a psychiatric crisis and they both come out in public to make a declaration of suffering. In the case of my cousin Maynard, he goes to the federal building in Mobile, Alabama and he says, "Someone needs to take me out of this country." He can't take it here anymore in America. That's literally what he's asking someone to do. Jordan Neely, according to The New York Times, according to video taken that day--

Kai Wright: Is asking for help.

Antonia Hylton: Is asking for help, "I haven't had food, I haven't had a drink. I'm fed up," is what he says. Immediately when I heard that story I thought of my dad's cousin, Maynard. I guess I found myself asking all the same questions that many of the nurses and doctors at Crownsville have posed to me about, is what we've got going on now better than this system we had in the '50s, '60s and '70s? When it comes to mental healthcare in America, are we doing more or better for Black Americans in particular?

I think when you see that Jordan Neely had about 40 prior interactions with whether that was police or that was mental health care service providers in the city, and that in each case he ends up back on the streets in New York still very much suffering, not getting proper care, not properly reconnected with family, and I look back at what happened to Maynard.

Kai Wright: Because we've got about two minutes left here. I think all of that leads me to a question that wraps us up that a texter has. The person says, "This is so angering, in the Black community I've seen a lack of trust of dentists, doctors, and any invasive testing. I've also experienced racism in medical care. It definitely affects our health outcomes. I particularly think Black women are given short shrift in getting diagnoses of successful medical care. What can we do to change this? In the 90 seconds or so we have here, how do you answer that?

Antonia Hylton: I'll tell you what the doctors and nurses of Crownsville, what many Black psychiatrists are telling me who I spoke to, and who you'll hear from in this book, a few things. They think that we need to recommit ourselves to building the community mental health care and reconstructing hospitals, not like the mammoth institutions we saw in the past, but by the actual specialized clinics politicians once promised us they would fund, that there should be a groundswell of movement around that they believe.

Many Black psychiatrists believe that we should teach people the same way we teach people CPR. We teach them what to do if there is a shooting at school or at their workplace, that we should teach people the signs of mental suffering, of what to do, of what the proper phone numbers are to call so that people can support loved ones or colleagues when they experience those moments. Then also get to the right people. It's not the police, it's not authorities who respond.

The other act that I think many of them would like to see more of are people being supportive of things like parks and green space and libraries and public schools, that the erosion of these spaces is contributing to a mental health crisis, particularly for young children in America right now. They believe that none of this is actually all that complicated. If we recommit ourselves to it and we make our voices heard, we have a much better system and outcome.

Kai Wright: Antonia Hylton is the author of Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum. Thank you so much for the book and for this conversation. Thanks to all our listeners, especially those who called in. I can confirm that according to ABC, San Quentin was built by inmates. Notes from America is a production of WNYC Studios. Check us out wherever you get your podcast and on Instagram @noteswithkai. This episode was produced by Suzanne Gaber. Our theme music and sound design is by Jared Paul. Matthew Marando was at the boards for our live show. Our team also includes Regina de Heer, Karen Frillman, Felice Leon and Lindsay Foster Thomas, and I'm Kai Wright. Thanks for spending time with us.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.