What Happens When a Political Project Dies?

BOB GARFIELD From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Last month, many Puerto Ricans were incensed by spring breakers and other visitors who flouted local rules imposed to reduce the spread of covid-19. Puerto Rico was one of the first U.S. jurisdictions to issue a mask mandate, and it maintains strict curfews. The pandemic wasn't politicized, and when it arrived amid earthquakes in the South and the protracted efforts to rebuild after Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico's fragile health care system was still able to cope. Tourists are always welcome, but as one local told NBC News, people can't come here and act as if the virus doesn't exist. They have a sense of entitlement and apathy I don't understand. For the mainland, the island has long been a locus of both entitlement and apathy. But next week, politicians, some of them anyway, will be paying attention. On April 14th, Wednesday at 1 p.m. Eastern Time, the National Resources Committee, which oversees territorial affairs, will consider two competing bills. One would provide for the admission of Puerto Rico as a state. The other would provide for true self-determination. Either would be historic. Both are deeply opposed by the GOP. There's also a rich history of division within Puerto Rico over what its status should be, but most agree that the current situation, this disenfranchised limbo, isn't it? OTM producer Alana Casanova-Burgess also is host of the La Brega podcast produced by WNYC and Futuro Studios. And in this episode, La Brega offers up some insight into that part of American history that the mainland mostly doesn't know and needs to understand. Here's Alana.

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS I've noticed that outside of Puerto Rico, many people seem uncomfortable calling the island a U.S. colony. In English, you'll hear the word territory or Commonwealth, protectorate even. And that used to be the case in Puerto Rico, too, but not anymore.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Hay muchos en Puerto Rico, muchos, muchos, aun dentro de su partido, que dicen que si que Puerto Rico es una colonia, por eso, es que se llama de descolonizacíon. [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Eso es ser una colonia completamente. [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Por que Puerto Rico es una colonia de los Estados Unidos. [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT no sea una colonia. [END CLIP]

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS People would twist themselves into pretzels to avoid the C word. And there's a reason for that.

YARIMAR BONILLA Puerto Ricans were promised that they were not a colony.

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS This is Yarimar Bonilla. Yarimar is a political anthropologist. She has a column in the Puerto Rican newspaper, El Nuevo Dia, and she's also written for outlets like The Washington Post and The Nation. That promise that Yarimar mentioned, about not being a colony, it's pretty much been broken. In 1952, Puerto Rico had adopted this new political status called the ELA, the Estado Libre Asociado, or free-associated state, which doesn't really mean much. In English, we call it a commonwealth. And what does that mean? Is it like the Commonwealth of Massachusetts? No. Is it like the Commonwealth of Canada? Also, no. Commonwealth doesn't really mean anything concrete, but it's the kind of word that made everyone feel better about the US having a colony. The Estado Libre Asociado, the ELA, promised self-governance, but not independence. It was a kind of compromise created by the island's first elected governor, Luis Muñoz Marín in order to massage the continued colonial interests of the U.S. and Puerto Rico and present a sovereign future to his residents, Marín came up with this label that sounded like decolonization.

YARIMAR BONILLA He thought that like since it had all this language of decolonization. He thought that he could set legal precedents to kind of if you build it, they will come. Like if you build it, they will decolonize - kind of idea. And then meanwhile, the United States, they're like, well, we're going to pretend that we're decolonizing, but we're not really going to decolonize. So, it's like both parts were kind of calling each other on their bluff. It kind of reminds me of this like Seinfeld episode that I love where like George Costanza meets up with the parents of his deceased fiance and he tells them he has a house in the Hamptons and they know it's not true

[CLIP]

GEORGE COSTANZA It's a two-hour drive. Once you get in that car, we are going all the way...

[DOOR SLAMS].

GEORGE COSTANZA...to the Hamptons [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA And they all get into a car and start driving to the Hamptons.

[ALANA CHUCKLES].

YARIMAR BONILLA And they also all know that the others know that it's all a farce.

[CLIP]

GEORGE COSTANZA Almost there.

FATHER IN LAW Now this is the end of Long Island. Where's your house?

GEORGE COSTANZA We go on foot from here.

FATHER IN LAW All right. [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA So basically, like we've been in a car with the United States, headed to the Hamptons, when we all know there's no house in the Hamptons. You know?

[BOTH CHUCKLE]

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS There's some indication that Luis Muñoz Marín and the U.S. Congress both knew there was no House in the Hamptons. In 1950, while testifying in a House committee hearing, he said, quote, If the people of Puerto Rico should go crazy, Congress can always get around and legislate again. That's what he said in Washington, D.C. But in Puerto Rico, he claimed this new status would be a definitive end, to quote, every trace of colonialism. Part of the promise of the ELA was that it was supposedly the best of both worlds. Self-governance with the protection of the U.S. military, and the mobility of a U.S. passport. It was also imagined as a key to prosperity, having a link to the wealthy U.S. while also being able to manage our own affairs. But that was 70 years ago, and recently this idea has been dealt some severe blows. 15 years ago, a recession became a debt crisis, which is now an austerity crisis. Then in 2016, during 2 Supreme Court hearings, the US government itself pushed the argument that Puerto Rico wasn't really sovereign after all. The next nail in the coffin came in 2016. It was a law named unironically, Ley Promesa, or promise. That's the federal law that installed a fiscal control board to manage the island's finances and implement austerity policies in order to service the debt. These series of events created an awakening. In response to the Promesa Law, protesters declared that the time of the promises was over.

[SINGING]

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS Se acabaron las promesas, the ELA had been a lie. Something between Puerto Rico and the U.S. had been broken.

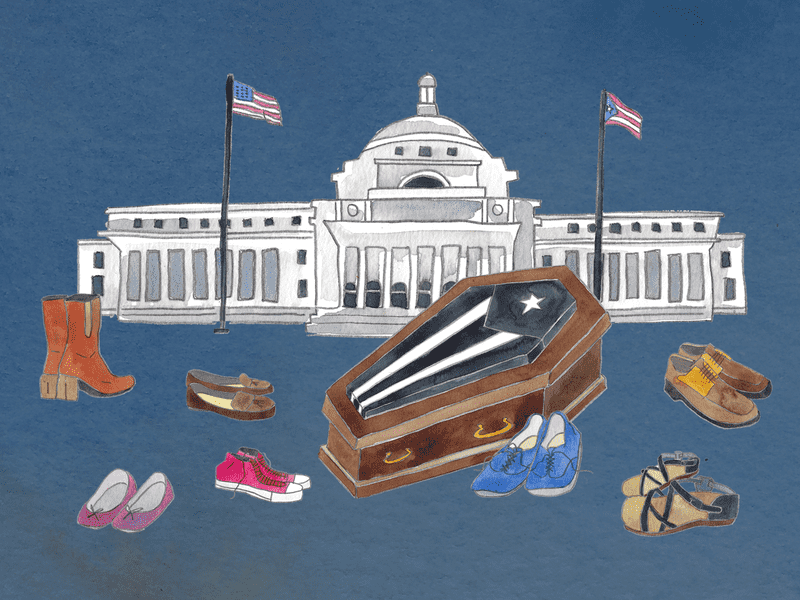

YARIMAR BONILLA After all these revelations, people started talking about the death of the ELA, the death of the Commonwealth, and I became really fascinated by that idea. Like what does it mean for a political project to die?

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS In what some called a sign of mourning, black and white Puerto Rican flags started popping up, instead of the red, white and blue one. There were murals denouncing colonialism, too. And then came the deaths from Maria. Not metaphorical, not performative, but thousands of lives lost in the aftermath. And here here is where maybe Puerto Rico could have used the benefits of the island's murky relationship with the U.S. to rebuild from the hurricane. Instead, President Trump threw his infamous paper towels and the White House slow walked funds. Leaving many residents without electricity for nearly a year. Some people are still living under tarps, 3 years later.

YARIMAR BONILLA Who feels decolonized in Puerto Rico, and who’s like we're good? I want to start at the beginning. I want to think about what was the ELA promise to be and who believed in that promise. Who said we had a house in the Hamptons?

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS Yarimar decided to start right at home, with her grandmother.

MONSY [SINGING] Ay, ay, ay, ay, canta y no llores...

YARIMAR BONILLA That voice you hear is my 93 year old grandmother, Maria Monserrate Fuentes Gerena, better known as Monsy. She loves to sing. In fact, it's hard to get her to stop singing.

MONSY [SINGING] Acercate mas, y mas...

YARIMAR BONILLA Like many Puerto Ricans. I grew up very close to my grandmother. She was always around telling me to fix my hair, asking me if I was really going to go out dressed like that and basically helping raise me along with my mother. During the pandemic, we spent lots of time joking around and filming funny videos for Instagram where her handle is Badmonsy.

YARIMAR, MONSY, YARIMAR's MOM [SINGING] Me levanté contento...

YARIMAR BONILLA This is us, with my mom, singing Bad Bunny.

YARIMAR, MONSY, YARIMAR's MOM por que dicen por ahi que están hablando de mi. Que se joda, que se joda, que se joda....

YARIMAR BONILLA No joke, my grandma really does love Bad Bunny.

MONSY Él hablo malo pero actúa bien.

YARIMAR BONILLA She thinks he has a potty mouth but a good heart.

MONSY Ay a mi encanta Bad Bunny! A mi encanta él.

YARIMAR BONILLA The pandemic has also given me a chance to discover her surprising brushes with history.

MONSY Yo fui a un cumpleaños de Munoz Marín. Yo te lo dije.

YARIMAR BONILLA It turns out she had gone to a birthday party for none other than Gobernador Luis Munoz Marin. She was invited by a suitor who coyly asked if she’d like to join him at a birthday function. When he explained who the party was for, she lost it.

MONSY Yo: que que? Yo me volví loca.

YARIMAR BONILLA I asked her what she wore to the special occasion. And unsurprisingly, she dressed in red. The color of Munoz's party. She wore a bright red pantsuit and a pava, the straw hat traditionally worn by Puerto Rican peasants. This was her homage to the color and symbol of Munoz's party. The populares. She's bummed that there weren't cell phones back then so she could have a picture, not just of her slammin outfit, but of this historic encounter.

[CLIP]

ANTHEM Jalda arriba va cantando Popular, jalda arriba siempre alegre, va riendo [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA What she remembers most fondly about those times is the conviction and commitment of the political leaders.

MONSY Ramos Antonini.

YARIMAR BONILLA She fondly remembers Mr. Ramos Antonini, the well-known black socialist lawyer who is one of the founders of the party. But her favorite, of course, was Luis Muñoz Marín. Just looking at him, she says, inspired confidence. She loves to talk about how he would go to the chozas of the jibaros. Homes with dirt floors and few belongings and have coffee with the residents in the little cups they fashioned out of hollowed out coconuts.

MONSY Él decia que sabía mejor ahi el café

YARIMAR BONILLA He swore the coconut cups made the coffee taste even better. Every time she tells the story, something about that small gesture of grace really gets to her. She's convinced that he really did love Puerto Rico and just wanted the best for it.

MONSY Él sentia, amaba a Puerto Rico, él lo amaba.

YARIMAR BONILLA This kind of uncritical nostalgia is a common staple among Puerto Rican abuelitas. But actually, Luis Muñoz Marín did a lot to erase rural life through his emphasis on industrial development. But for my grandmother, it was all about eradicating the poverty that she grew up with. Bread, land and liberty. That was the promise, and my grandmother believed in it because she saw it with her own eyes. Lands were being massively redistributed, even her uncle got a parcel. During this time, industry was also arriving. Homes and schools were being built.

MONSY Y siguió mejorando y siguió mejorando.

YARIMAR BONILLA For my grandmother, everything was getting better and better. The ELA really did seem like the best we could hope for. The best of all possible worlds.

DEEPAK LAMBA NIEVES The people of Puerto Rico felt – hey, el ELA, lo mejor de los mundos.

YARIMAR BONILLA This is Deepak Lamba Nieves. He's a development planner at the Center for a New Economy, and a good friend. Deepak argues that the ELA was never really about decolonizing Puerto Rico. It was about using Puerto Rico as an economic experiment as a counterpoint to communism during the Cold War

[CLIP]

ADVERTISEMENT Apartment complexes, bilingual schools, modern hospitals, luxury hotels, progress can be seen everywhere. This is Puerto Rico, Progress Island, USA. [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA To the outside, the ELA was sold as an economic success story, but all that economic growth was built on unsustainable compromises. From the beginning, there was an overreliance on tax incentives which Washington could enact and take away as it pleased. Once the tax incentives were taken away, companies started fleeing Puerto Rico and the government took on massive debt to stay afloat. By 2016, it became clear that Puerto Rico was descending into what economists literally call a death spiral. Everyone began putting pressure on Washington to pass some kind of debt relief. Among those making the rounds on Capitol Hill was Deepak. He thought...

DEEPAK LAMBA NIEVES Hey, there's another way of addressing the Puerto Rican dilemma with the economic situation and also the debt issue.

YARIMAR BONILLA He was initially confident about the impact he could have. He assumed he would be taken seriously. After all, he's a smart guy who works at a fancy think tank where they had developed a solid, cost effective plan. But Washington politicians had no time for him. Deepak says they made him feel like he was begging for a handout– or worse, praying for mercy. He returned from D.C., convinced that Puerto Rico was quite simply a colony, and that the island just doesn't matter to the United States. If you read a news story about Puerto Rico's debt crisis, you will most likely see it accompanied by a picture of desolate Paseo de Diego. This pedestrian mall used to be a bustling commercial district. Visitors from surrounding parts of the Caribbean would come and load up on goods to sell back home. My mom was a master seamstress. Every year we would do her back to school shopping. Happily combing through the big bolts of fabric at stores like La Riviera, where we would purchase fabric for a whole semester's worth of new handmade dresses. Now, that's a long-lost memory. Most of those stores are shuttered, and the few that remain are struggling to survive.

[MUSIC PLAYING FROM CARAVANA]

YARIMAR BONILLA Alana and I were recently Rio Piedras at a time when it felt much more active. There was a Caravana – a political rally where people get in their cars and drive around following a candidate during election season. We were asking folks there if the ELA had died, and one guy was quick to answer.

[CLIP]

MAN Él ELA un engaño. No murió, ni siquiera nunca nacío [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA It never died, he said, because it was never born. He was there supporting a new movement in Puerto Rico that wants to stop talking about status and focus on other fundamental issues like government corruption, gender violence and the need to audit the debt. The Caravana was for the campaign of a young politician named Manuel Natal. That he narrowly lost the race to be San Juan's mayor, but even this near victory was astonishing, given that Natal is from a brand-new political party.

[CLIP]

YARIMAR So how would you define the ELA?

NATAL It was, el maquillaje de la colonia? It was a way of putting a little bit of makeup [CHUCKLES] on our colonial relationship with the United States.

YARIMAR A little lipstick on the pig?

NATAL Yeah [CHUCKLES] the pig is the colony, not the people of Puerto Rico

YARIMAR That's good! [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA Natal actually used to really believe in the ELA. He comes from a family of Populares and was once a rising star in the party. But a few years ago, he made a radical decision and became an independent, citing corruption among his colleagues. Then, along with other progressive leaders, he helped found a new political party called: Movimiento Victoria Ciudadana. Its members have different visions. Many are pro-independence, but some are pro-statehood and others, like Natal, are soberanistas, meaning they want more local sovereignty while still retaining their ties to the U.S.. But they all agree on one thing – decolonization is necessary, and we need a new process for deciding which status we want. For decades, the political parties in Puerto Rico have been organized around status options, and every couple of years we undergo these performative votes that are described as plebiscites or referendums. Back in the late 60s, when NBC was reporting on the first plebiscite vote, they called out, right away, the irony of the spectacle,

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Most Puerto Ricans, even those who favor a commonwealth, agree on one thing. This plebiscite is at best only a temporary solution. The United States is not legally bound by its results, and neither is Puerto Rico.

YARIMAR BONILLA At best, these are little more than opinion polls. In the most recent one, last November, the statehood option won by a slim margin, receiving 52 percent of the votes cast. But these plebiscites are non-binding. They're not tied to any legislation and have no support in Washington. They're basically another bluff. It's like once again, we're getting in a car heading for the Hamptons.

NATAL So what are our other alternatives?

YARIMAR BONILLA Natal's party proposes what they call a constitutional assembly. In which representatives of each political option could negotiate directly with Washington, the terms of each status choice. And what would this do? Ideally, it would bring concrete answers to enduring questions like would we have dual citizenship if we were independent? Would we have access to federal programs like Pell Grants as an associated republic? And maybe the most delicate question, but also the most important one, would any of these options be tied to reparations, for over 120 years of colonial rule? I started the pandemic posting videos of my grandmother on social media, joking that she was la influencer, but by the time the political campaigns were in full swing, she had become a bona fide social media sensation.

MONSY Dime hija.

YARIMAR BONILLA ¿Por quien vas a votar?

MONSY Pues, yo quiero un cambio, pero un cambio radical.

YARIMAR BONILLA radical?

MONSY radical.

YARIMAR BONILLA I posted a video of her in a rocking chair, where I asked her how she was going to vote this time around. She surprised us all by saying that she supported the pro-independence candidate, Juan Dalmau. The conventional wisdom was that only young voters were supporting the alternative candidates like Natal and Dalmau, and that older voters were afraid of change. Her video went viral. Dalmau even used it for one of his TV spots, and then the morning shows came calling.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Como todo una influencer, como Bad Monsy ha conquistado las redes sociales por sus videos. [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA She then wrote and sang a political song that also took off:

MONSY [SINGING] Ni azules ni colora’os, ni azules ni colora’os. Yo quiero la patria nueva que nos propone Dalmau! [HOST LAIGHS],

YARIMAR BONILLA And the weekend before the election, then Mao himself actually came to visit her and brought her flowers, which put her over the moon.

MONSY No lo puedo [unintelligible]!

YARIMAR BONILLA After a lifetime of voting for the Populares and of supporting the ELA, her public support of an independentista was surprising, but it doesn't mean that she wants independence itself.

MONSY No, no independencia por ahora

YARIMAR BONILLA She told me she voted for Dalmau, simply because she thought he would make a good governor. As far as the status, she felt like that could be dealt with later.

MONSY Entonces despues se podia bregar con lo otro. Tu sabes? Poco a poco.

YARIMAR BONILLA Like a good popular, she thinks we should just kick the status can down the road. But you know who is really kicking the can down the road, really hard all the time? The U.S. Congress, they refused to commit to anything or to even speak clearly about why it insists on keeping Puerto Rico as an ambiguous transition land. So where does that leave us? Honestly, I don't know. But I'm skeptical of all the options currently on the table. For example, when I consider independence, I get excited about the possibility of being our own country. But then I look around at our neighbors in the Caribbean and see that many have the same challenges as Puerto Rico, indebted economies, austerity regimes, huge diasporas, the challenges of disaster recovery and battles over corruption. Independence is clearly not a silver bullet. It doesn't guarantee sovereignty. Instead of battling the fiscal control board, we might end up battling the World Bank or the IMF. But when I consider statehood, I think of Hawaii and how the native population there was shut out of much of the prosperity and development that statehood supposedly ushered in. Or I look at the movement for black lives in the U.S. and the discrimination suffered by people of color in the States. And it makes me wonder if anything other than second class citizenship will ever be available to us. So, I end up back where we've been for all these years – at an impasse. Yet something feels different about the current moment. The signs of change might be subtle, but they're there. In the ubiquity of the black and white protest flags, in the dark lyrics of a Bad Bunny song, and in the transformations at the ballot box as thousands moved towards alternative candidates. So perhaps if the death of the ELA and the end of the promises means anything, it's the realization that the world we deserve is not something that can be promised, conceded or guaranteed, but it's also not something that we can keep waiting for.

[PROTEST CHANTING & MUSIC]

BOB GARFIELD Coming up, that one-time Puerto Rico absolutely owned the U.S.... In basketball.

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.