What 100 Years Of Audio Can Tell Us About Black Americans and Belonging

[music]

Speaker 1: You must be able to put yourself as nearly as possible into the place of the other fellow in order that you may be able to see his point.

Speaker 2: I'm absolutely convinced that our nation or the world will never rise to full maturity until somehow we can get rid of the long night of man's inhumanity to man until we can get rid of racial injustice.

Speaker 3: The Negro artist, the Negro writer in particular, does have a particular vantage point, which is a little different from the white writer. We have the peculiar stance of being within and without, we're never really quite into the mainstream yet we are obviously entirely completely American.

[music]

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright. Welcome to the show. You probably recognize some of the voices you just heard. You almost certainly recognize the people they belong to, Giants of American History and specifically Black Americans who spent their lives trying to make this thing called the United States work out for them. We start by hearing those voices today because we're going to do something a little different and hopefully really fun. First off, here's the context for today's show. WNYC, New York Public Radio, which makes this show, it turns 100 years old this year.

The station maintains this massive archive and I must say important audio archive that covers those 100 years. People here have been going through those audio archives as we celebrate our birthday and they've come across a bunch of stuff that they thought would be of particular interest to the Notes from America Family. One of our editors, she has lined up some of that audio to play for me and for you and a friend of this show and of this public radio station, Christina Greer.

Now Christina is an associate professor of political science at Fordham University, author of a couple of books about the history of Black politics, and just a general nerd about New York City history in particular. She's also the host of the podcast, The Blackest Questions from theGrio Podcast Network, and just an all-around smart lady and my friend. Hey Chrissy.

Christina Greer: Hi there.

Kai Wright: Are you down for this?

Christina Greer: Listen, I always tell people I love two things, cities and Black people. Let's rock and roll.

Kai Wright: [laughs] We're going to do cities and Black people and the audio. Let me stress, Chrissy and I are hearing all of this tape for the first time right along with all of you. It's a bit of a reality show setup, I guess. We're going to just listen and see what each selection brings to mind. Okay, let's get started with the first cut, Josephine Baker.

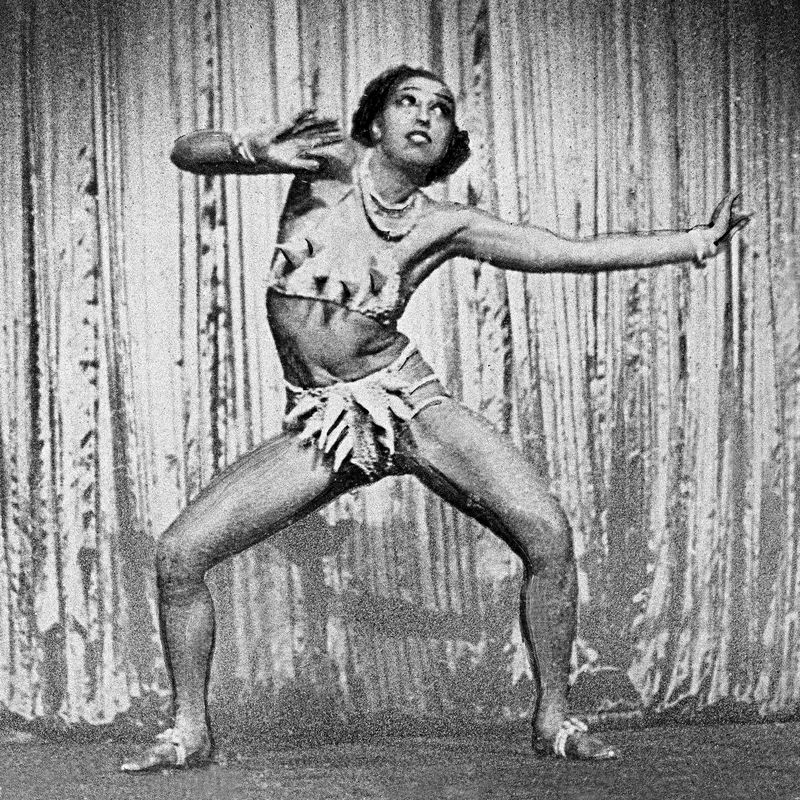

All right. This is going to be 1964. She'd have been 60 years old at this time. It's a part of a speech she gave in New York at a meeting of the Overseas Press Club. Just quickly to give everybody some context, if you don't know Josephine Baker. She left the United States at 19 years old to go to France in 1925 to become a world-famous singer and performer-

[MUSIC - Josephine Baker: J'ai Deux Amours]

Kai Wright: -and a somewhat risqué one. She famously showed a lot of flesh. [laughs] Here is international dance and voice sensation Josephine Baker.

Josephine Baker: Now, I have come to my native land. I have come here through wanting to come for a long time and you know the story I haven't been able to because some parties, some people thought that I was, well, at a certain time, a little bit too broad-minded, or frankly speaking words or saying expressions and doing the things that wasn't at that time very well accepted. I wasn't able to come back to this land with which I was born, which I love because I think everybody loves their land.

I have one thing in common with many people that I love all lands because I love and appreciate all people. I love them because they have accepted me and in my way, adopted me. I've had the privilege of seeing today many people who have come and say, "Hello Josephine. I remember you've come to such and such a country." It's wonderful like that. Don't you think it's the right way of thinking, of respecting people from different lands? Don't you think it's how it should be?

[applause]

Josephine Baker: I think so because it's nobody's fault if somebody is like an egg and just hatched in one part of the world or the other doesn't make him less a human being or a respectable person. Here I am here in New York, which to me is the cradle of all humanity because in this town, one can see all peoples and one can appreciate all people and love them too.

With this great broad-minded way of thinking in New York City, I came back. I came back here because I thought that right here when I was allowed to come back, I knew that I would be understood. I knew that I would not be criticized, and I knew that people would try to understand why I'm still on the stage trying to make a living in an honest way for my children because these are my children.

Kai Wright: Okay. That's Josephine Baker at the Overseas Press Club in New York in 1964. She's 60 years old. She started on vaudeville at 15 years old and became wildly wealthy in the course of her career, was deeply political. That's some of her reference to being allowed back into the country. She adopted 12 children in the course--

Christina Greer: Of different races.

Kai Wright: Of different races. She was Madonna before Madonna [laughs] in that regard. If you don't know Josephine Baker, that's the context for what you just heard. Chrissy, I'd never heard Josephine Baker's voice, I think.

Christina Greer: That's the first thing I just wrote in my little notes so I don't forget things is these accents. I'm so fascinated by the evolution of accents over time. I always think about Charlie Rangel. You don't hear that Harlem accent as much anymore because it's a mélange of so many different groups, really buttressing one another. I know that there's so many different American accents in New York accents. Even the authentic New York accents have changed so much over time. Just listening to the WNYC archives, it's like, "Wow, we don't sound like that on the air at all."

Kai Wright: We don't.

Christina Greer: A few things. One, she says, I was too broad-minded. I'm just thinking back, it's like she's Black and she's a woman.

Kai Wright: And queer.

Christina Greer: And queer. This tri-part intersectionality, where it's like, "Yes, that might be a little too much for America. Isn't allowed for America in 2024." It might be a bit too much in the 20th century. I think about this idea of being allowed back in. I think about someone like Paul Robeson, or Josephine Baker, people who were excommunicated from this country in a lot of ways and really made to feel that you are not welcome and then oftentimes in a legal sense like, "No, you're definitely not welcome."

Kai Wright: "You're definitely not welcome."

Christina Greer: "Not only you're not welcome, you ain't coming back until we decide." This idea of native land, I've written a lot about this for Black Americans especially where this is our land. It's like, "We're the JBs." where it's like, "Just Blacks." We don't have a particular country in the Caribbean or on the continent of Africa. This is our native land. What do we do when it rejects us, not just emotionally, but physically it rejects us? Then this concept that she talks about lands that have adopted me. I feel that way. I travel internationally extensively and I think about cities where I feel at home. When I'm on the continent I feel some kind of way because I really love East Africa and I like West Africa. Don't get me wrong. I love food in West Africa.

Kai Wright: Don't start it. Don't start no mess.

Christina Greer: I'm not going to start the jollof rice wars. I'm not going to do it. I love East Africa. That's where I feel most at home. I feel like Berlin is a home to me. Belfast, I've never felt more at home than when I was in Belfast in Vietnam. I was like, "Oh, okay. My spirit just felt at ease." Now, I think that says something about my spirit because-

[laughter]

Christina Greer: -[unintelligible 00:08:57] places. I love her idea of she's loving all lands in this. Humans are like an egg and it doesn't matter where you crack it. How we can feel place in space and love. This idea that New York City is a place to be understood. That's why people come here. There's a reason why Stonewall happened in New York as opposed to any other major city in the United States. There's a reason why so much activity starts here because this is a place where people can come to be their true selves and see themselves in other people. We see ourselves as global citizens.

Kai Wright: Certainly Josephine Baker belonged to the world. We talk about New York was a place where people come to be understood, but she went to Paris to be understood. I think about that moment of early 20th-century post-World War I and the band of the Harlem Hell Fighters that went to France and became decorated soldiers, but also exported jazz to the globe and this massive fascination with Black art and jazz in particular, that erupted as a consequence of Black soldiers in World War I and Josephine Baker, little Josephine Baker at 19 years old, is stepping into that moment and becomes the embodiment of it. It's so funny to think about. I imagine that that was not pure.

I think of her as this 19-year-old wearing, she famously put on the banana dress, so she was basically naked, but with a string of bananas and some pearls, and danced in this sexual way. I can imagine what some of the people watching that were into that thought of this Black woman as this savage. The ideas--

Christina Greer: A banana is a very deliberate fruit for a Black person--

Kai Wright: Exactly, the ideas that went into that, but the way she took that, and was like, "I don't care. Y'all can think what you want. This is my art," and became rich. This is another thing, she started selling skin-darkening cream

Christina Greer: Ooh.

Kai Wright: -to White people in France is where a lot of her money came from. It was called Baker Skin, and she was selling skin-darkening cream. These people bought it up and I think she had something to do with hair, caulking your hair that she sold to white people-

Christina Greer: Oh wow.

Kai Wright: -as well and was making bank. [laughs] Then took that money and funded politics in both the United States and France.

Christina Greer: She says, "Some people think that I'm ridiculous," but there's this method behind the madness, I guess you would say. When you think about some of the early Black stars on the radio or television and the debates, it's like, "Oh, you're being a minstrel." They're like, "But I'm actually being able to fund things to change the world. In some ways, I'm sacrificing myself so you can throw these slings and arrows, but I use my money to actually make a difference." She's a lot more than pearls and a banana skirt and that was for sure.

Kai Wright: I'm not mad at those pearls and that banana skirt either, get it a girl.

[music]

Kai Wright: This is Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright. My guest is Fordham University political scientist, Christina Greer, and we are celebrating WNYC's centennial anniversary by digging through the archives and hearing some voices. Coming up, we'll hear from a comedian, a congresswoman, and a tennis champion. Stay with us.

[music]

Kai Wright: It is Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright, and I've been working at WNYC, which makes this show for, gosh, coming up on 10 years in one way or another. The history of this station goes way, way back and this year, WNYC turns 100 years old. To mark the occasion, I am digging through the archives.

We've got this massive archive of incredible audio of people who throughout the 20th century have been trying to make a place for themselves in these United States. I am joined as we listen to this audio by Christina Greer. She's associate professor of political science at Fordham University. She is host of The Blackest Questions podcast from theGrio. She is my friend and a really smart lady and we're listening to some tape. Chrissy?

Christina Greer: I'm going to put that on my CV.

Kai Wright: [laughs]

Christina Greer: [chuckles] Friend of Kai Wright and really smart lady.

Kai Wright: Friend of Kai and is a really smart lady. All right. We've heard from Josephine Baker. Now, we're going to hear it from Althea Gibson. In 1957, she was a tennis champion and was given a key to the city of New York. This we're going to hear is her acceptance speech when she's receiving that key to the city. Again, Chrissy and I are going to hear this for the first time alongside all of you. That's the fun here. We're just firing some of these gyms from the archives of the past century and seeing what it sparks. Let's hear Althea Gibson in 1957.

Althea Gibson: Yes. This field of sports is something great, which reminds me of a joke. This is concerning tennis since that's the field I'm in, which reminds me of the joke between the devil and the Lord. The devil got a bright idea in his head one day, and he went up to the Lord and said, "I'd like to have a tennis match with you and those that you have." The Lord looked at him and said, "Are you serious?" He said, "Sure, I'm serious." He said, "You must be kidding." He said, "No. Well, will you agree to it? Will you want to?"

He said, "Well, how can you win? You can't win. I have all the best players up here. I have Tony Trabert, I have Gardnar Mulloy, I have Vic Seixas. Holding all those players, how can you win?" He says, "Do you agree to a tennis match with me?" He says, "Well, knowing that you don't have a chance, yes, I agree, but tell me, how do you think you can win?" The devil said, "Well, you may have all the best tennis players in the world, but I got all the umpires and the linesmen down here."

[laughter]

Kai Wright: Tennis star, Althea Gibson, cracking jokes while receiving the key to the city. Tell me about Althea Gibson. I don't know much about her, but I can't imagine this Black woman in the 1950s is a tennis champion.

Christina Greer: Yes, she's a tennis champion. She's the Venus and Serena way before Venus and Serena. I don't know the deep, deep archive of Althea. All I know is that when you saw her play-- and there was a great documentary about her that I saw at the Barnard Documentary Film Festival many, many years ago. She had the body of almost like a ballerina, obviously, she's breaking color barriers. Obviously, tennis has had a lot more diversity over the years, and it starts--

Oftentimes, we talk about Arthur Ashe, as we should. He's a fantastic tennis player, but there's no Arthur Ashe without Althea Gibson. In some way in the patriarchy, she gets lost in the shuffle.

Kai Wright: Truly.

Christina Greer: We talk about Arthur Ashe as the quintessential beginning of Black American tennis. This idea of winning a Grand Slam in the '50s as a Black woman, it was a huge deal. When Venus and Serena were winning and the racism that they experienced and still experience.

Coco talks about it, all of the young Black tennis stars still talk about going on these tours and what they're experiencing, not just from their colleagues, but from the fans, and sometimes even the umpires as well. To try and put yourself in her shoes traveling, sometimes not being able to stay at the same hotels.

Thinking about this country and race vis-a-vis sports helps us understand the evolution of this country, how far we still need to go. You know what? A lot of people endure to push this country forward through sports. It's this idea that a key to New York City. What must that mean to a girl who grew up playing tennis? "I hit this ball around and you mayor think that I am special among the specials," which is just quite beautiful.

Kai Wright: That was Althea Gibson. The next voice brings us to somebody who I know is dear to your heart, Chrissy, and who is a voting rights activist from the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Let's just get her in our ears real quick.

Interviewer 1: Say your name and where you're from.

Ms. Fannie Lou Hamer: Ms. Fannie Lou Hamer. 626, East Lafayette Street, Ruleville, Mississippi.

Kai Wright: All right. We're going to hear a longer cut from Fannie Lou Hamer, but give us the thumbnail sketch if for somehow, if people don't know Fannie Lou Hamer's name, introduce them quickly.

Christina Greer: Just a brilliant organizer from Mississippi, but really across the south, known as a real thorn in my favorite President's side, Lyndon Baines Johnson. She talked a lot about sharecroppers and the plight of Black Mississippians and also poor white Mississippians trying to register to vote. She had death threats.

She had to move. She was arrested, she was assaulted. The horrors that she endured she was forcibly sterilized. They used to call it a Mississippi appendectomy where you take Black women and you sterilize them without their knowledge or consent.

A child of the South, again, thinking about the complexities of how oftentimes we like our leaders, Black leaders, to look and sound a particular way. We think about the civil rights movement. Rosa Parks was the third person chosen to be the representative because she was married and she was of a certain complexion and a certain educational background and she wasn't Claudette Colvin who was an unmarried mother. Fannie Lou Hamer is brilliant and eloquent speaker.

Kai Wright: She's everything that you're supposed to hate about Black women.

Christina Greer: Exactly.

Kai Wright: She was large body, dark-skinned country, impolite.

Christina Greer: Yes and not apologetic. I'm finishing up this book about Fannie Lou Hamer and Barbara Jordan and Stacey Abrams and thinking about, Barbara Jordan and Fannie Lou Hamer had a baby 50 years later, it'd be Stacey Abrams. These three Black women, Black American women of the Black South, and what that means to organize both inside and outside of politics.

Fannie Lou Hamer was like, "Well, these parties down here ain't doing nothing for us. Maybe we should start our own party. Maybe we should start our own economic collective and raise our own animals and grow our own food." Just the brilliant foresight of this woman.

Kai Wright: All right, so let's hear more of Fannie Lou Hamer. This is an undated interview, but it is likely before her famous 1964 testimony at the Democratic National Convention. Here's Fannie Lou.

Fannie Lou Hamer: My husband was arrested in February in '63 because I went to the City Hall and I told the lady that work at the City Hall where we have to go and pay for our water. I was charged for using 9,000 gallons of water. I told her, I said, "That's impossible for me to use 9,000 gallons of water." I said, "But I will pay you for it." She said, "Don't pay me Fannie." Said, "We will check it again." I was waiting for them to check it. Then on the 12th of February, I had gone to Leflore County, trying to get some petition that we could send in to the federal government to try to get commodities to the people that was in Leflore County that was suffering like some of us were suffering here in Ruleville.

When I got back, the water was cut off like it would usually be cut off, that I would have two young men to always cut the water off when I was out of town. I just turned the water on but after I turned it on, I felt like maybe it could have been some kind of trap. I had the water cut back off, and I went down to my husband's cousin, and I got a couple of buckets of water, and right after that the policeman came and he said, I would have to go up and talk to the mayor.

I went up to talk to the mayor. It was myself and James Jones and [unintelligible 00:22:18] Conway. We went up to the city hall to talk to the mayor, and he said my ignorancy would cost me $10. Say, for me, turning that water on it was just like I had broken a store or in a bank or something, and I would have to pay $10 extra, plus $4.06 for the water, plus another dollar that he would charge would make $15.06. I said, "I don't think it's fair."

Then that same night, Mr. Marlin came to arrest my husband because he had a warrant. Charles McLaurin, one of the field secretaries for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, had enough money to keep my husband from going to jail that night. Then we was asked to meet at the city hall the next day for the trial.

We went up the next morning for the trial, and when we got there, I told the mayor, I said, "You know it's not fair." I said, "It was impossible for us to use 9,000 gallons of water when I've been in South Bend, Indiana, visiting my sister, the kids was in school and my husband hunt every day. I don't have running water in the house." I said, "We just couldn't use that much water." He told the police there to lock my husband up. He said, "You told that woman that you wouldn't pay that bill." I said, "I didn't tell her that." I said, "I told her I would pay it, and she told me that she was going to have it checked."

I said, "You wasn't even around when I was talking to Ms. Carruthers." He said, "Well, you're going to have to pay a $100 cash fine to get pap out." He told the other police, Mr. Gibon, to take my husband and lock him up, so they lock my husband up.

My husband got out of jail. McLaurin paid the fine and got my husband out of jail. Then in April, I attended a voter registration workshop, and actually it was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference workshop in Dorchester at MC and Touch Georgia to take citizenship training. When we got ready to catch the bus right around the corner from here, we saw people there with guns in trucks, and they had dogs but we got on the chartered bus anyway and went on to this voter registration workshop. When I returned home after then, I began teaching citizenship classes to teach people how to register and vote.

Kai Wright: That's Fannie Lou Hamer, the famous voting rights activist from Mississippi. An undated interview we think sometime before 1964. I think one of the things that stands out to me in that Chrissy is we think about voting and we think about public access. She's talking about water.

Christina Greer: And the intimidation, that's what that was about. When she's saying it was $1 here and $15 there and $100, we have to remind ourselves, this is the 1960s. That's a lot of money. That's definitely a lot of money to former sharecropper in Mississippi. The intimidation tactics vis-a-vis money and fines just try and silence people and clearly, she was like, "Well, it's not working. You can keep fining me. We'll figure out the money."

I also think she namechecks SCLC, she namechecks Nick and you think about this network of organizations, entertainers from the north doing shows to funnel this money back down to the south. This is why the vote is such a massive endeavor. People were getting lynched. People were getting raped, people just getting murdered and ending up in a river, all for trying to register to vote. Then this Northern money that can come through and help support these organizations that are trying to change the US South.

Kai Wright: Speaking of northern money and northern artists, let's hear our next person because it's around the same time as this Fannie Lou Hamer interview, there is an interview with comedian and activist Dick Gregory.

Interviewer 2: The Negro problem in America has developed into a crisis. Whites against Negro and now Negroes against Negroes. Those who stand for nonviolence, against those who want blood. Mr. Dick Gregory, the Negro comedian, has been risking his life fighting for civil rights through nonviolence. He's my guest today here to tell us about the Negro problem.

Dick Gregory: It's a white problem because show me a so-called Negro problem and I'll show you dumb white leadership. The Wallaces, the Wagners, the Rockefellers. See, we do not control anything, so we cannot have a problem. We have people that say, "What about the Negro crime rate?" What would the white man's crime rate look like if the Negroes took over America tonight and hired Black Muslim as police? See, I got a man out there that's guarding me don't even like me in the first place.

You see, all our life, the white man said, "Get like me. Be like me, and I'll accept you." The day the white man quit killing each other, we won't have anyone to imitate.

Interviewer 2: Are you saying, then, that the Negro superior than the white morally?

Dick Gregory: No, I'm not saying the Negro is superior to the white morally, I'm saying that the minority will always ask the majority to let me integrate with you. The white man is in a minority worldwide and with jets bringing the world closer together, and a few years the white man in the world will have the same problem the Negro in America have because he will be outnumbered 90 to 1 the same way we are. He should look and look at our problem because one day he's going to have to ask the world's Black man to let me integrate with you the way we are asking the American white man to let me integrate.

Kai Wright: That's Dick Gregory in 1964. For people who don't know Dick Gregory, one of the first really successful Black comedians in the country. He used to say that he was one of the first Black comedians that didn't have to shuck and jive, that he would just stand with his two feet planted and tell jokes, and that was new. He was a civil rights activist, close ally of Martin Luther King. Was one of the people who sent a lot of money south to support those movements. As you have heard, he had a sharp tongue. His autobiography in 1964 was titled Nigger.

Christina Greer: I have some of his albums--

Kai Wright: Oh yes?

Christina Greer: Yes I think I still listen to my dad's record collection so I have some of his albums and I've collected some over the years. A political comedian, which I think some of the through-line with a lot of the folks that we're talking about, it's like, "You have to have humor to live in this country. You have to have humor to be a Black person in order to not just thrive, but to purely survive." There has to be some sort of laughter underneath all of the really harsh truths which he was known. He also was very clear, like, "I'm going to have as many children as possible to populate."

Kai Wright: He had 10 children or something like that?

Christina Greer: Yes. Just like, "I will populate the Earth with Black people." I love this idea, I say this to my students all the time and I can see their minds just exploding, but I don't like the term minority because I always explain to them that I'm a global majority.

Kai Wright: That's right. I'm a woman, there's more of us out here, and I'm a person of color. This framing that I have about myself and where I fit into the world, not just this country, is something that a lot of them haven't thought about because they're just like, "Well, I'm just a minority." It's like, no, no, no, no. There's no just, especially if we think of ourselves as global citizens, the way, say Josephine Baker did.

We still have to remember this is the 1960s. He's still risking his life to do this. He's very clear that he knows that he's doing that. To just organize people in an intellectual fashion in that country.

Kai Wright: He's on the FBI watch list we know.

Christina Greer: He's saying this stuff, and he knows it before Malcolm X and Martin Luther King are assassinated. I love his framing of like, "This is not a Black people problem. It's a you problem. It's not a me problem."

Kai Wright: This is a white folks problem.

Christina Greer: "If you want me to emulate your behavior, look at your behavior." I think that's the larger conversation that now globally as he predicted, other countries are saying, "Listen, you want to sit here and clutch your pearls and say like, 'Why are people behaving this way?' It's like, because you did it. We're just looking at you."

Kai Wright: That's right.

Christina Greer: "Stop pretending that you didn't do what I saw you do."

Kai Wright: One of his jokes I loved, he tells his joke, I shouldn't be doing this because I'm not going to come anywhere close. [laugh] He says when he was at a sit-in in Mississippi, I think and they tell him we don't serve colored folks here. He says, "Well, I don't eat colored folks any place so bring me some pork chops." They say, "Well, we don't serve pork chops, sir." The Klan shows up and he is like, "Well, bring me a whole fried chicken then." They bring the whole fried chicken out and the Klan says to him, "Whatever you're going to do to that chicken we're going to do to you." He said, "I picked it up and kissed it on the ass and said, be my guest."

[laughter]

Kai Wright: Dick Gregory.

Christina Greer: Dick Gregory.

Kai Wright: All right. I'm Kai Wright. You're listening to Notes from America. My guest is Christina Greer, associate professor of political science at Fordham University. Host of the podcast, The Blackest Questions. Just ahead, we are going to continue our listening party from WNYC's archives. The station turns 100 years old this year, and we're going to hear the voices of two women who made history and changed America. That's coming up. Stick around.

[music]

Katerina Barton: Hey, it's Katerina Barton from the show team at Notes for America with Kai Wright. Something happens to me when I listen to this show, no matter the topic or the guest, I can always think of someone I want to tell about what I just heard and I do. If you're thinking about who in your life would enjoy this episode or another episode you've heard, please share it with them now. The folks in your life trust your good taste, and we would appreciate you spreading the word. If you really want to go above and beyond, please leave us a review. It helps more people, the ones you know and the ones you don't find the show. I'll let you get back to listening now. Thanks.

[music]

Kai Wright: It's notes from America. I'm Kai Wright, and today we are having a listening party. We're celebrating 100 years of WNYC, the station that produces this show by digging through the station's audio archives, dating back a century. I'm joined by Christina Greer. She's an associate professor of political science at Fordham University here in New York and host of The Blackest Questions from theGrio Podcast Network. She and I are hearing these audio selections for the first time alongside all of you, and just seeing what they stir up for us.

We've been hanging out in the 1960s, and before we transition from that decade, we have to hear from one of the most iconic Black speakers of the time, Malcolm X. We're going to hear an interview from 1961 when he's still a spokesperson for the Nation of Islam, and he's talking with interviewer Eleanor Fischer, who is asking him to share what he thinks of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Eleanor Fischer: Well, it seems to me that actually the basis of distinction here is one, is a distinction of goals. Dr. King's goals are quite different from yours. He believes in integration, complete integration in society. Is that correct?

Malcolm X: Well, that's where Dr. King is mixed up. His goal should be the solution of the problem of the Black man in America. Now, not integration, integration is the method toward obtaining that goal. What the Negro leader has done is gotten himself wrapped up in the method and has forgotten what the goal is. The goal is the dignity of the Black man in America. He wants respect as a human being. He wants recognition as a human being. Now, if integration will get him, that, all right, if segregation will get him that, all right, if separation will get him that, all right. After he gets integration and he still doesn't have his dignity and his recognition as a human being, then his problem is still not solved.

Eleanor: Well, isn't this exactly what Dr. King is looking towards and that is the day when the Negro will be treated with dignity. Wasn't this after all the result of the Montgomery Bus Boycott?

Malcolm X: No, because I don't think you can-- having an opportunity to ride either on the front or the back or in the middle of someone else's bus doesn't dignify you. When you have your own bus, then you have dignity. When you have your own school, you have dignity. When you have your own country, you have dignity. When you have something of your own, you have dignity. Whenever you are begging for a chance to participate in that which belongs to someone else or use that which belongs to someone else on an equal basis with the owner, that's not dignity that's ignorance.

If I may add, for instance, King and these others will say that they're fighting for the Negro to have equal job opportunities. How can a group of people such as our people who own no factories, have equal job opportunities competing against a race that owns the factories? The only way the two can have equal job opportunities is if Black people have factories as well as white people have factories. Then we can employ whites or we can employ Blacks just like they can employ whites or they can employ Blacks.

As long as the factories are in the hands of the whites, the housing is in the hands of the whites, the school system is in the hands of the whites, you have a situation where the Blacks are constantly begging the whites, can they use this or can they use that? That's not any kind of equality of opportunity, nor does it lean toward one's dignity.

Kai Wright: That's Malcolm X being interviewed by Eleanor Fischer in 1961. This is while he's still spokesperson for the Nation of Islam, a time period where there's still this divide in Black politics between Malcolm X as the embodiment of one set of ideas and Martin Luther King as the embodiment of another. What do you think, Chrissy?

Christina Greer: One, I think it's so interesting to hear his voice and to hear how similar Denzel Washington was in the--

Kai Wright: Right?

Christina Greer: Trips me out just a little bit. I'm sure some of the listeners out there like, "Okay, good, I'm not crazy." I was like, wow, he really did nail it and he was clearly robbed, the Oscars. This idea of integration as the method and the goal being dignity Kai, the first thing I thought about was 2020 and the Summer of Reckoning and how Black folks were demanding this dignity, this equality, this same opportunities. The same conversations he's talking about in 1961. The response was Juneteenth as a federal holiday.

Now no disrespect, I'm glad we got the federal holiday, but that wasn't actually the demand. That wasn't the goal. The goal was dignity. The goal was stop killing us in the street. The goal was actually let's have a real evaluation of policing across this country and have some subsequent conversations that didn't necessarily happen. I think this is like to respect history and have these conversations in the modern day these are some of the tense conversations Black folks are having about reparations.

Some people are like, reparations now reparations forever. I'm one of these folks. It's like, okay, so you get a lump sum. Does this money just go back into white institutions? What does that then do for the Black community? I think these are still some of the tense conversations that we're trying to grapple through that I think Malcolm X and Dick Gregory and MLK to be fair, were having in the 1960s and we're still having them. There have always been several different factions and ideologies as to how Black people are supposed to advance in this country.

The scale of Black ideology has been vast for quite some time. What I also appreciate about this archival clip though is like, it's Malcolm X 1961. He and MLK aren't necessarily on the same page. Then as they get closer to their deaths in the late '60s, we see them after Malcolm X goes on pilgrimage he goes to Mecca, he has Hajj and he comes back a changed man shoulder to shoulder with other Muslims. Then Martin Luther King's like, "Well listen LBJ calls me the N-word."

Kai Wright: Enough already.

Christina Greer: "I'm leaning on the shield over here, but maybe we need to--" The Vietnam War really radicalizes him his famous Riverside Church speech in New York. Not surprising. How the two of them co-mingle in a real deep respect for where the other one was coming from. Because it's like, "Oh, now I see what you're saying," and then it's lights out.

Kai Wright: Then it lights out for both of them. Okay, we've been in the '30s, we've been in the '50s and '60s. Now let's move forward to the '70s and '80s. The first thing we're going to hear is Shirley Chisholm, she was the first Black woman elected to Congress. she sat down for an interview with Casper Citron who was a longtime radio and TV host in New York. Let's hear a bit of that conversation.

Shirley Chisholm: The Democratic Party really has taken Blacks for granted. There's no question about it.

Casper Citron: And Puerto Ricans?

Shirley Chisholm: Yes, that's right. Many of the minorities who've been trying to move out into the political mainstream have been taken for granted by the Democratic Party, yet it's supposedly the party of the masses. On the other hand, the Republican Party hasn't paid that much attention. Maybe the Republican party now is going to try to move in the direction, capture the Blacks back, and go back to those days in history when the Blacks were part of the Republican fold.

I don't want to sit here and tell you what I think happened, that they raised all of that money and they got all of those Blacks. If you look at those who attended the dinner, and you look at those who were selling the tickets, I think that would speak for itself. People connected to the administration. People who enjoyed contracts-

Casper Citron: Office holies.

Shirley Chisholm: Office holies. That's politics. The Democrats have their dinners too, and you have big people that enjoy certain favors. That's the mere American politics moves. The very fact that Blacks came together openly in spite of the fact that other Blacks in the country are saying that Nixon is not sensitized or attuned really to the needs of Black people, it's an indication that everybody's going to really have to get on guard now, from here on in. Everybody's going to have to be on their guard in terms of the Black vote for the future in this country.

Kai Wright: Ooh, that's 1972, Shirley Chisholm. It feels very 2024. What do you think? What do you think Shirley Chisholm would have to say about this political moment we're in?

Christina Greer: Whew. I really would've loved to have her thoughts in 2008 and 2016-

Kai Wright: Oh wow.

Christina: -of Barack Obama versus Hillary Clinton and Hillary Clinton again. This conversation about the Democratic Party taking Black people for granted is not a new conversation. The movement of Black people to the Republican party allegedly is not a new conversation. We still have to remember a few things that were true then and are definitely true now. Black people are overwhelmingly supportive of the Democratic Party way more so than Latinos, Asians, and obviously definitely whites. Even when we see a little bit of wiggle room, it's still exponentially more than every other racial and ethnic group.

There is a party capture that is there. In the 21st century, I would love to hear what Shirley Chisholm has to say about the Republican party that has essentially chosen their lot with white nationalists. Where are Black people supposed to go with a party that believes in swastikas and the Confederate flag? We don't want that nonsense. We also don't want success on the backs of other groups because we know that that's a short-lived strategy. Something that Dick Gregory and Malcolm X and Josephine Baker know all too well. This is actually, it's a conditional acceptance that we know is a shell game. Why would we do that? Partisan politics, of which Shirley Chisholm was very good at. Don't forget. We can't understate this, the first Black woman to US Congress from Brooklyn. I'm telling you.

Kai Wright: This didn't happen because she was whatever, just street organizer.

Christina Greer: No.

Kai Wright: This is a woman who knew how to do politics.

Christina Greer: Who knew how to do politics, who spent some time in Albany. Who cared about teachers, who cared about real issues that have always mattered to families writ large and continue to matter. She wasn't organizer in the sense that we think of like a Fannie Lou Hamer, or even Stacey Abrams to an extent. She was a political operative as well. She's the shark. I always think about this interview is in 1972 where it's like this is when she's running for the presidency and white women are saying like, "We need a woman on the ballot." She's like, "I'm here." Like "Sorry, by woman we meant white woman."

Then she goes to Gary, Indiana, big Black conference, and they're like, "We need a Black person on the ticket." She's like, "Hey, I'll do it." All the people are like, "Yes, by Black person we meant Black man." She finds herself also in this political no man's land. She's got this great political mind, and the time in this country isn't accepting of a Black woman with her political acumen to be at the top of the ticket.

Kai Wright: Okay. Our next voice from the archive is also a very recognizable one. It takes us into the 1980s. It's the first one we we'll hear that belongs to a living legend. This person is still with us, activist and author Angela Davis. This is from 1982. It's also an interview with Casper Citron who is talking to Angela Davis about her book, Women, Race and Class.

Casper Citron: Angela, even though it's not in the book do you feel that under the present Republican administration, civil rights and civil liberties are going backwards?

Angela Davis: Very definitely. Very definitely. It appears as if the Reagan administration wants to turn the clock back to the 1920s, to the period before the struggles of the '30s, to the period before we achieve Social Security and unemployment compensation, welfare, et cetera.

Casper Citron: Undoing the new deal in other words.

Angela Davis: Undoing the new deal. Exactly. This is a period I think that's very similar to the historical moment following the overturning of radical reconstruction. I think we can learn a lot.

Casper Citron: You mean in the South?

Angela Davis: Yes. Exactly

Casper Citron: The carpetbag of days.

Angela Davis: Exactly. That was one of the most progressive moments in the history of this country when Black and white people together passed some of the most progressive legislation.

Casper Citron: It was only temporary.

Angela Davis: Why was it temporary? It was temporary because the forces of racism, and I don't want to imply that it was entirely the ex-slaveholders from the South. It had to do with the new monopoly capitalists from the North who needed to have a malleable working class who wanted white workers and Black workers to be fighting one another in order that it might be possible to oppress all of them with ease. That has been one of the primary functions of racism. I think that it's important for white people to recognize the way in which they suffer as a result of racism. Not only people of color suffer the horrors of racism, but it is against the interest of the vast majority of people in this country.

Kai Wright: That's Angela Davis in 1982 while on a book tour about her book Woman, Race and Class. What do you think was on her mind at the '82 when she's out selling this book?

Christina Greer: We can't underestimate just how brutal the Reagan era was to Black people and to poor people and especially poor Black people. Those are three different groups. I think her book about class, we talk a lot about gender, race, and the intersectionality. Class for Angela Davis, who's brilliant by the way. I think sometimes with living legends, it's like, "Oh yes, she's smart. She did all these things and--"

Kai Wright: Wear the T-shirt, put the poster after you--

Christina Greer: Yes. She's gorgeous and all the things, but it's like, no, no, no. She's a prolific writer. When you read some of her stuff, it's like, "Oh, this is actually one of the greatest thinkers of our time."

Kai Wright: Quite frankly, a lot of it's quite challenging.

Christina Greer: [laughs] Yes. She goes deep in the woods. Get a thesaurus. This idea of turning the clock back during the Reagan era, and that was a big concern. All democracy, especially in this country, is temporary as she says. We've been doing a victory lap, "Oh, Obama two terms," and you put your democracy on the wall and put a frame and clap yourself on the back. It's like, "We did it." "No, you didn't." Because it's a series of daily, hourly, nowadays, choices that we have to make as a nation collectively that we've failed at. Just ask women who no longer have a right to choose in several states across this country.

This larger project of turning things back, the hosts ask Angela about like, "Oh, it's about turning back the new deal." Nowadays it's not about turning back the new deal and the great society. It's about turning back the Civil Rights Act. It's definitely about turning back the Voting Rights Act. It's about turning back the Immigration Act and the Housing Act. Then it definitely made me think of LBJ's quote that talks about if you can convince the poorest white man that he's better than the Negro, you can pick its pockets all day long. Martin Luther King talked about that as well.

It's like, "White people look around your life is not better. All they're selling you is whiteness." That's the only thing that you have to keep you warm at night because you don't have a job, you don't have good schools, you definitely don't have dental care. He's walking around the country. Martin Luther King is murdered organizing poor people. Organizing Black people is one thing. Organizing poor people is a much larger group. You keep poor white people-

Kai Wright: March on Washington Against Poverty.

Christina Greer: -for jobs and freedom. Now imagine if white people paid attention. It was like, "Hey, let me get on this."

Kai Wright: "Jobs? I want some jobs."

Christina Greer: "I want some jobs too."

Kai Wright: You were pointing out though, that Angela Davis, we talk a lot about, many people think about the way she thinks about gender and race, but not about class, and that class was a really important part of her analysis.

Christina Greer: Yes, it's a huge thing because the thing is class is an organizing principle. This is where I think she deviates from say like a Bernie [unintelligible 00:49:24]. Bernie is like, "Class, class, class." Class in this country without an analysis of race is ridiculous.

Kai Wright: Or without her analysis of gender.

Christina Greer: Exactly. What makes her so brilliant is that she recognizes that these are tripart conversations. To just have a conversation about class is important, sure but that doesn't get to the nuance and the brutality of what class does in this country.

Kai Wright: Chrissy, we got to stop.

Christina Greer: I know.

Kai Wright: Christina Greer is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Fordham University. Host of the podcast, The Blackest Questions, and author of How to Build a Democracy. Thank you so much for this time, Chrissy.

Christina Greer: Thank you.

[music]

Kai Wright: That concludes our own archival listening party, but WNYC's Centennial Celebration is just getting underway. You can learn more about special programming, including events on the air, online, and in person at wnyc.org/100. Our thanks to the WNYC Archives and the Municipal Archives for preserving and providing the audio we heard on today's episode. Special thanks to WNYC Archivist Andy Lanson. There are more than just interviews in the archive. There are countless live performances, so we will go out on one from 1950. It's Miles Davis playing alongside JJ Johnson, Stan Getz, Tadd Dameron, Gene Ramey, and Art Blakey.

[MUSIC - Miles-Davis: Max Is Making Wax]

Kai Wright: Notes from America is a production of WNYC Studios. This episode was produced by Karen Frillman and Lindsay Foster Thomas. Mixing and sound design this week by Mike Kuchman. Our team also includes Katerina Barton, Regina de Heer, Suzanne Gaber, Varshita Korrapati, Matthew Mirando, Jared Paul, and Siona Petros. There's more about our show and this episode on Instagram @noteswithkai. I'm Kai Wright. Thanks for spending time with us.

[MUSIC - Miles-Davis: Max Is Making Wax]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.