The Wastebook

THE WASTEBOOK

Undiscovered is produced for your ears! Whenever possible, we recommend listening to—not reading—our episodes. Important things like emotion and emphasis are often lost in transcripts. Also, if you are quoting from an Undiscovered episode, please check your text against the original audio as some errors may have occurred during transcription.

ANNIE MINOFF: I’m Annie.

ELAH FEDER: And I’m Elah.

ANNIE MINOFF: And this is Undiscovered, a podcast about the backstories of science. Sheila Patek has always obsessed about whether her work was important.

SHEILA PATEK: I mean always. There's this little voice in the back of my brain saying well what are you doing for the world. I know that sounds kind of ridiculous but it's really true.

ANNIE MINOFF: Sheila’s a biologist. She’s a professor at Duke University. And she studies an animal called the mantis shrimp.

ELAH FEDER: Yeah, more on them in a second.

ANNIE MINOFF: But she thinks this what are you doing for the world question? It comes from her family.

SHEILA PATEK: My older sister teaches developmentally disabled preschool children and my younger sister teaches STEM classes in a public high school in Maine.

ELAH FEDER: Her mom taught high school Latin and French. And for the teachers in Sheila’s family, it’s pretty clear what they’re doing for the world—

ANNIE MINOFF: Right—

ELAH FEDER: This is not some kind of abstract idea. They are shaping the next generation. It’s normal dinner time conversation for them.

ANNIE MINOFF: And then at some point in this conversation, the three teachers turn to Sheila, and it’s like, “So Sheila...How’s it going with the shrimp?”

ELAH FEDER: Yeah, no pressure! So Sheila says, the pivotal moment that helped her family understand just what exactly she’d decided to do with her life, it came in grad school. Her research got written up in The New York Times.

SHEILA PATEK: And when they read this stuff in The New York Times and they realized, “Oh! It's in the section about discoveries, like new discoveries,” they had this aha moment <<laughing>> of, “Ohhhh, that's what she's doing! She's discovering stuff.”

ANNIE MINOFF: Sheila has made a career discovering stuff about mantis shrimp and other equally bizarre creatures. She deeply believes that what she’s doing is making the world a better place. And then, in December of 2015, this happens:

SHEILA PATEK: It was my birthday weekend. <<laughing>>

ELAH FEDER: You can probably tell this doesn’t end well. So Sheila, she’s in the lab. She’s answering some emails before she heads home for the weekend, and then she gets one...

SHEILA PATEK: ...that had in the header, Good Morning America, ABC News query...

ELAH FEDER: An ABC reporter was emailing to get Sheila’s reaction. How did Sheila feel about her research being put in a wastebook?

ANNIE MINOFF: Now at this point, Sheila had NO IDEA that her work had been put in a wastebook. This was news to her. But she knew what a wastebook was.

ELAH FEDER: A wastebook, or sometimes it’s called a waste report—

ANNIE MINOFF: Or an oversight report—

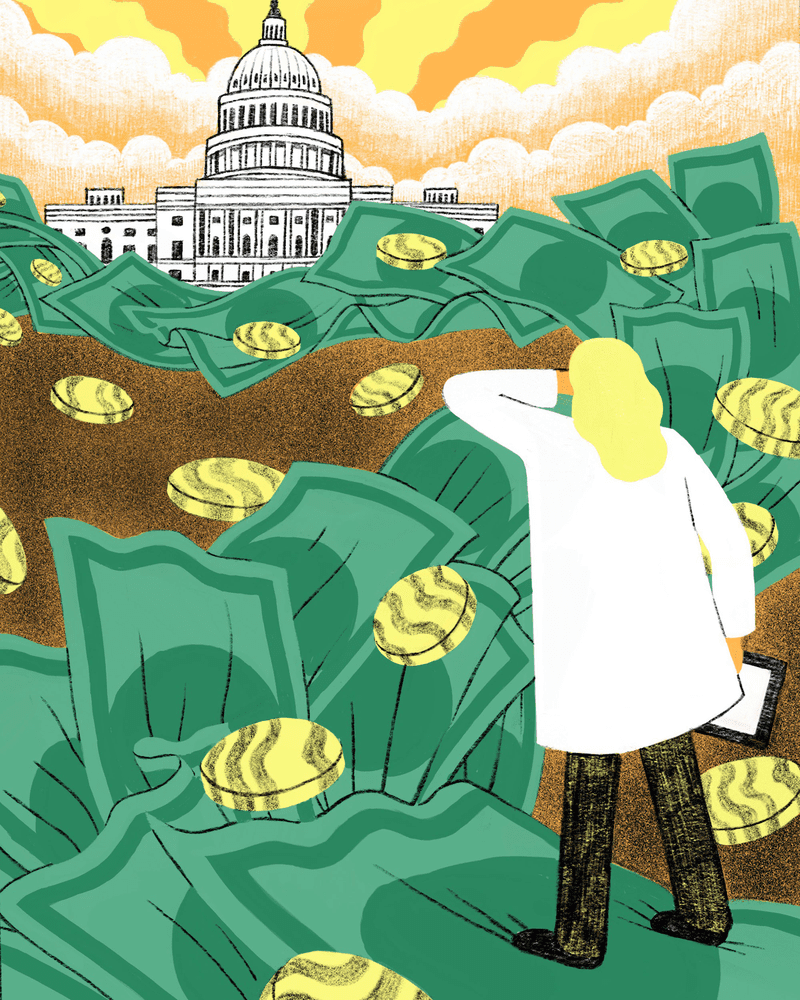

ELAH FEDER: Right, lots of names. It’s a document that a member of congress puts out. Basically, a big list of projects funded with federal money that this congressperson thinks didn’t deserve that money.

ANNIE MINOFF: And that’s what had happened to Sheila. So a U.S. Senator had learned about her shrimp research, decided this was a waste of federal money, put it in his wastebook.

SHEILA PATEK: When I read that email, I have to say, my stomach sort of fell through the floor.

ELAH FEDER: Because she knew what was coming.

NEWSCASTER 1: You will not believe what your government is wasting your tax dollars on…

NEWSCASTER 2: One hundred examples of government waste…

JEFF FLAKE: Duke University got money to actually pit shrimp against each other…

NEWSCASTER 3: Price tag? 707 thousand dollars….

JEFF FLAKE: This stuff? You can’t make it up....

ELAH FEDER: Today on Undiscovered: A shot is fired. An accusation is made, and answered! We’ve got a story about what happens when scientists and politicians go head-to-head.

ANNIE MINOFF: On one side, you’ve got the scientists. Saying that politicians in DC, they don’t understand—or they willfully misunderstand—science. They aren’t funding science enough.

ELAH FEDER: And on the other side, the politicians are saying, “ Hey, we’re spending billions of dollars a year on scientific research. What are we getting out of it?”

ANNIE MINOFF: Well today, those two sides are gonna meet in a marbled office building on Capitol Hill, as Sheila Patek comes face-to-face with the Senator who called her science “waste.”

ELAH FEDER: That’s coming up on Undiscovered.

*************

ANNIE MINOFF: The animal that got Sheila into this whole mess is a truly bizarre creature. I mean mantis shrimp are WEIRD.

SHEILA PATEK: Yeah! So you think shrimp and you think the little pink thing with the tail that's partially peeled on your cocktail plate or whatever if you eat those. And these animals—mantis shrimp—are really not shrimp.

ANNIE MINOFF: Mantis shrimp are stomatopods, technically. The great-grandaddy of the stomatopods and the great-grandaddy of your modern cocktail shrimp? They diverged about 4 hundred million years ago. And according to Sheila, these mantis shrimp? They kind of look like cartoon characters.

SHEILA PATEK: I don't know how else to put it.

ELAH FEDER: You showed me some pictures of these, Annie? Oh my—

ANNIE MINOFF: They’re crazy!—

ELAH FEDER: Wow. They literally come in every color of the rainbow. There’s this one species in Florida that’s hot pink with flashing spots!

ANNIE MINOFF: The shrimp in Sheila’s lab, they’re kind of a light, grassy green, with speckles?

SHEILA PATEK: And they have googly eyes! So they have these oblong eyes on stalks that track you. Each eye separately! So you walk up to this multi-colored thing, it comes right up to look right back at you and—moving both eyes around—and you just know right away that this is like an alternative life form that you're dealing with! <<laughing>>

ELAH FEDER: These mantis shrimp will stare you down with their google-y eyes because they’re not afraid of you. And that’s because they are packing lethal weapons.

ANNIE MINOFF: They have this mouth part—it’s a mouth part but it kinda looks like an arm—and it ends in this rounded hammer shape? And the shrimp use this hammer to smash open snail shells, because this is their food. They wield these hammers at accelerations as fast as a bullet coming out of the muzzle of a gun. And they do this underwater!

ELAH FEDER: Sheila says, when you walk by the aquariums in the lab, the shrimp…

SHEILA PATEK:...might come out and smash the tank when you go by. You might hear them pounding some snails. It's pretty— There are lots of crackles and pops especially if people just fed them snails.

<<Small tapping sounds>>

ELAH FEDER: Ennnh, so like a bunch of clicking. But imagine you’re a shrimp or a snail, big boom—

ANNIE: Yeah—

ELAH FEDER: for you!

ANNIE MINOFF: So the study that landed Sheila in the wastebook, it was actually by one of her grad students. And it was about those lethal weapons that the shrimp have.

ELAH FEDER: Mantis shrimp fight. A lot. And most of these fights are over housing. In Sheila’s lab, housing means a little burrow made out of a sawed-off PVC pipe.

ANNIE MINOFF: And watching these fights, like with your naked eye, you have no idea what is happening. You see these two little shrimp, they’re about two inches long, bright green. And they kind of run into each other, and something really fast that you can’t see happens, and they run away, and they do it again and they do it again....

SHEILA PATEK: And you kind of start holding your breath to see what's going to happen! Because they're zooming back and forth and finally all of a sudden it’s just over.

ANNIE MINOFF: And nobody’s dead!

SHEILA PATEK: You know nobody's been hurt. They just settled it. So someone gets their own territory and the other one is like never mind. I quit. <<Laughs>>

ELAH FEDER: The study that ended up in the wastebook was about what was happening in those fights. It turns out that shrimp are using those hammers to repeatedly bash each other on a super strong, armored tail plate.

ANNIE MINOFF: Boom boom boom boom boom really fast!

ELAH FEDER: Yeah but more like k k k k k k. And the shrimp that lands the most hits, wins the real estate. Which raises some interesting questions. Like, what is this armored tail plate made out of? How is it that it’s enduring so many hits without getting damaged? It suggests some pretty cool engineering applications.

ANNIE MINOFF: The Wastebook, however? Did not exactly describe the study like this.

JEFF FLAKE (TV CLIP): This year we have a shrimp fight club.

ANNIE MINOFF: Yeah they decided to go with Shrimp fight club.

JEFF FLAKE: Duke University got money to actually pit shrimp against each other.

ANNIE MINOFF: That is Senator Jeff Flake on Fox News’ On the Record.

ELAH FEDER: Jeff Flake is a Republican senator from Arizona. And he’s the one who put Sheila’s research into his 2015 wastebook. His list of the most wasteful uses of taxpayer money that year.

ELAH FEDER: And so you know, Senator Flake’s office declined our requests for an interview, both with the Senator and a senior staff member.

ANNIE MINOFF: Jeff Flake is a fiscal conservative. He’s a crusader against congressional earmarking, which is, you know, this practice of sneaking goodies into the budget for your constituents. He is frugal and very proud of that fact. A few years ago, he reportedly said he’d only paid for three haircuts in his life.

ELAH FEDER: His wife Cheryl actually cuts his hair.

ANNIE MINOFF: And He LOVES puns. Which are all over the wastebook.

ELAH FEDER: Flake’s wastebook is straight-up campy. In 2015, the full title was The Waste Book: The Farce Awakens! Ha? Pretty good! Ok! The Star Wars reboot was just about to come out, and the whole report is Star Wars themed.

ANNIE MINOFF: Here is Jeff Flake introducing his wastebook on the Senate floor.

JEFF FLAKE: It’s my hope, my only hope that this report gives congress something to chewie on….

ELAH FEDER: Chewie?

ANNIE MINOFF: Chewbacca?

ELAH FEDER: Oh! God…<<laughs>>

JEFF FLAKE: ...before debt and deficit saddles tax payers, and they finally strike back.

ANNIE MINOFF: The cover of the wastebook? It features a cartoon of Flake wielding the lightsaber with which he is presumably ready to laze the fat from the federal budget. Flip to page seventy-eight, and you will find a full 3 page write-up of Sheila’s Shrimp Fight Club. Plus a price tag: Seven hundred seven thousand taxpayer dollars.

ANNIE MINOFF: So one of the things I’ve noticed about the wastebooks, is there’s kind of this, like there’s a lot of jokes.

BRYAN BERKEY: Yeah!

ANNIE MINOFF: That’s Bryan Berkey, former congressional staffer.

BRYAN BERKEY: The point of those is kind of, A, it’s written from the Senator, right? So it’s showing their personalities a little bit. But B, it’s trying to, you know, if someone’s going to take time out of their day to read about the government, you know, it’s helpful for them to be a little lighter.

ELAH FEDER: Bryan Berkey did not help write Jeff Flake’s wastebook. But he’s helped write other waste reports for Senators Tom Coburn and James Lankford, both from Bryan’s home state of Oklahoma.

ANNIE MINOFF: These days, Bryan’s executive director of Restore Accountability, a non-profit that educates young people about the national debt. And Bryan points out, it is not just science spending that gets criticized in wastebooks.

ELAH FEDER: In Flake’s ‘The Farce Awakens,’ science projects are about a quarter of the entries.

ANNIE MINOFF: As for what counts as “waste”?

BRYAN BERKEY: Coburn used to say, you know if ninety percent of people would agree that this is not a priority for the federal government? Then we'll include it. And you know it might turn out that, you know, the other ten percent are those that listen to your podcast. <<Annie and Bryan laugh>> And that's ok. That's, that’s fine.

ELAH FEDER: Bryan says, basically, look. We wastebook writers, we’re not anti-science. But budgeting is about priorities. And the Senators Bryan worked for? They wanted federally funded research to advance national interests. Economic development, for example. Or National security. Or health.

ANNIE MINOFF: And he says, yes, the government should totally fund science.

BRYAN BERKEY: We don’t come to this from the perspective that we’re a bunch of luddites that don’t understand, you know, the importance of basic science and research, right?

ANNIE MINOFF: But maybe money’s being spent in the wrong places. A few years ago, the NIH director said, you know, maybe we’d have an Ebola vaccine right now it it weren’t for all those budget cuts over the years. So Bryan says, ok, not enough money for Ebola…. But we have money for this stuff in the wastebook?

BRYAN BERKEY: And it's not meant to you know, pit one against the other necessarily, but that's kind of Congress's job right? Budgeting is our job.

ELAH FEDER: Resources are limited, we have a twenty trillion dollar national debt…

BRYAN BERKEY: Some of these projects hiding behind the veil that all science is good science is just, you know, we just don’t agree with that.

ELAH FEDER: And this is basically the message that Senator Jeff Flake took to ABC in December 2015 when he released his wastebook:

JEFF FLAKE (TV AUDIO): A lot of those studies are very legitimate and useful. But a good number of them, ya think, who in the world thought up this stuff.

GRETA VAN SUSTEREN (TV HOST): But somebody’s gotta ok this. Who’s the person who’s saying ok to this stuff. Who’s writing the check?

ANNIE MINOFF: Great question from Greta Van Susteren. She was a Fox anchor at the time. Who IS writing the checks?

ANNIE MINOFF: Where does your lab get money?

SHEILA PATEK: Yeah. So I'll walk you through this process.

ELAH FEDER: Sheila paid for this so-called “shrimp fight club” with money from the National Science Foundation. The NSF funds basic science and engineering research. Which means it’s research that’s not geared toward any immediate application.

ANNIE MINOFF: So, if you want some of that sweet, sweet NSF cash, what you gotta do, you type up your grant proposal, send it to the NSF. NSF gathers the top scientists in your field. They rank the proposals, and give out the money. And chances are you walk away with nothing. Because three quarters of NSF proposals, they don’t get any money.

ELAH FEDER: Yeah and in Sheila’s field it’s more like ninety percent don’t get any money.

SHEILA PATEK: The competition is extremely fierce. It is very, very difficult to get a grant.

ANNIE MINOFF: Ok, but Sheila does!

ELAH FEDER: She gets a grant!

ANNIE MINOFF: She gets a grant for nine hundred thousand dollars, to be distributed over 5 years. So she’s basically rich.

ELAH FEDER: Right. Except now she has to knock off four hundred thousand dollars - ish? Roughly four hundred thousand dollars which is going to Sheila’s university for overhead.

ANNIE MINOFF: Her lab building…

ELAH FEDER: Her utilities... Now she’s got about five hundred thousand dollars left, which works out to..

ANNIE MINOFF: Divide by 5 years—

ELAH FEDER: Right. Divide by 5 years, a hundred thousand dollars a year. That goes to pay a postdoc, a grad student, pay for everybody’s conference travel, a summer program that brings grade school teachers to Sheila’s lab….

ANNIE MINOFF: And it pays for a shrimp fight club.

ELAH FEDER: Yeah how much was that?

SHEILA PATEK: What I can tell you is that it's in the order of only a couple of thousand dollars. If that much.

ELAH FEDER: This was one of the things that really irked Sheila about the wastebook. It made it sound like she’d spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on just ONE study. When instead she was spending it on multiple studies, on training young scientists, on having this program where she mentors grade school teachers.

ANNIE MINOFF: And so sitting there, at her desk, on her birthday weekend, she had a choice to make. She could ignore the wastebook. Wait for the news cycle to move on. But she didn’t. She did not want to slink away like a mantis shrimp who’d just lost a fight! A burrow-less mantis shrimp! She decided to fire back at Senator Flake.

ELAH FEDER: Strike back, even.

ANNIE MINOFF: Make the case for why mantis shrimp matter.

SHEILA PATEK: And then it becomes something constructive. And not that miserable sinking feeling where you have to hide or just feeling like, “Man what is up with politics! Why am I, you know, the focus of this now!” Just so stupid at some level! But I felt like, I deserve to have a, have a chance to explain why what we do is important for the broader goal of explaining why science is important to the world.

ELAH FEDER: Sheila drafted a statement. Duke splashed it on their website. And it explained how her research could have military applications.

ANNIE MINOFF: Flake’s response? Here he is speaking to KFYI’s Mike Broomhead:

JEFF FLAKE: And they tried to make some connection between this and then helping our troops, <<laughs>> and I just fail to see it.

MIKE BROOMHEAD: I don’t— I don’t know if you’re supposed to be talking about this because we all know the first rule of shrimp fight club is you don’t talk about shrimp fight club! <<laughing>>

JEFF FLAKE: That’s right, that’s right. Brad Pitt’s gonna come beat me up!

ELAH FEDER: Sheila’d made a statement. Flake fired back. And she figured that was the end of it.

ANNIE MINOFF: And then? She got another email. An invitation to Washington D.C. Would she come to Capitol Hill and present her research to members of congress?

ELAH FEDER: Coming up, the tensest, weirdest science fair you’ve ever attended, as so-called spendthrift scientists meet congress.

ANNIE MINOFF: And Sheila confronts the Senator who called her work a waste of taxpayer money.

SHEILA PATEK: <<Laughing>> I mean I almost passed out. I FREAKED OUT.

ELAH FEDER: That’s after the break, on Undiscovered.

****************

SHEILA PATEK: Okay. The trip to D.C….

ANNIE MINOFF: Three months after her research showed up in Senator Flake’s wastebook, Sheila Patek got an invitation to D.C. It was for a reception, hosted by two science advocacy groups. And the idea was researchers who’d been singled out in these waste reports, they’d go to the Hill. They would set up in the Senate office building. And congresspeople would drop by, and the scientists would explain the value of their work. Basically make the case that the wastebook got them wrong.

ELAH FEDER: So in April 2016, Sheila’s standing in this beautiful marble room, in front of a poster about mantis shrimp.

ANNIE MINOFF: Naturally.

ELAH FEDER: And she’s surrounded by all these so-called pilferers of the public purse.

ANNIE MINOFF: Mm-hm.

ELAH FEDER: A few feet away there’s the scientist who put monkeys in hamster balls on treadmills.

ANNIE MINOFF: Also the public health researcher who inspired this headline: “Feds wonder why fat girls can’t get dates.” <<Elah sighs>> And then there’s Sheila.

SHEILA PATEK: You know one thing that we heard a lot was please do not get mad at the people who show up.

ELAH FEDER: Flake wasn’t the only politician on the invite list. In the last decade, wastebooks have taken off in D.C. There’s a handful of congressmen who now publish their own takes on the waste report with slightly different spins.

ANNIE MINOFF: Senator James Lankford has his “Federal Fumbles.” John McCain has “America’s Most Wasted.” There’s Rand Paul’s “The Waste Report,” Steve Russell’s “Waste Watch”... All had been invited. All of them, you might’ve noticed, are Republican.

ELAH FEDER: But that wasn’t always the case. The guy in whose footsteps all wastebook writers follow—the founding father of the wastebook! He was a Democrat. Senator William Proxmire from Wisconsin.

MELINDA BALDWIN: Proxmire is someone who is unafraid to take strong stances. He is an early advocate of campaign finance reform. He was a very early critic of the Vietnam war…

ELAH FEDER: That’s science historian Melinda Baldwin. She’s written about Proxmire and early science funding fights.

MELINDA BALDWIN: He’s also a diet and jogging enthusiast.

ANNIE MINOFF: Melinda says one time, during this debate about whether or not the Senate should approve funds for a new gym…

MELINDA BALDWIN: Proxmire gets up and he says that's a waste of taxpayer money. None of you need a gym. You should all learn to jog and I will teach you how <<laughs>>

ANNIE MINOFF: Proxmire actually had a book about jogging. You Can Do It! Exclamation point! Senator Proxmire’s Exercise, Diet, and Relaxation Plan.

MELINDA BALDWIN: But that moment I think was very much in kind of Proxmire’s grand tradition, because the other thing that he’s really famous for is being an aggressive critic of government spending.

ELAH FEDER: Proxmire hated waste. He wanted to root it out. And in 1975, he hits on a brilliant idea.

MELINDA BALDWIN: The Golden Fleece Awards.

ANNIE MINOFF: The Golden Fleece awards work like this. Every month, Proxmire will award a prize…

MELINDA BALDWIN: Imagine “prize” in air quotes here because it's not a prize. It's a badge of dishonor.

ANNIE MINOFF: A prize to the most egregious use of taxpayer money. And these “prizes” get attention. Because the press releases? Kind of funny.

MELINDA BALDWIN: They're funny and a little mean.

ANNIE MINOFF: The punniness of Flake’s wastebook? That is classic Proxmire. And Proxmire goes after science.

ELAH FEDER: And Melinda says, it’s not that Proxmire was against government funding of science per se. It’s just that he didn’t want to fund stuff that seemed like it would never pay off.

ANNIE MINOFF: And I asked Melinda: We’ve been doing this waste report thing for four decades. Has the argument changed? Or are we just dancing the same dance?

MELINDA BALDWIN: I think it's kind of the same dance. I think that in a way we're all still dancing to Proxmire's tune.

ELAH FEDER: So Sheila’s come all the way up to D.C. for this very awkward science fair.

ANNIE MINOFF: Very awkward.

ELAH FEDER: And she’s there to make the case that mantis shrimp matter. And by this point, she’s spent a lot of time thinking about how you break out of this dance. How do you talk to a Senator who’s called your work waste?

ANNIE MINOFF: And she thought, it comes down to what you value.

SHEILA PATEK: People value science for different reasons. For VERY different reasons. Some people value science because we discover new things about the world. Other people feel that science needs to be directed toward solving human problems…

ELAH FEDER: And Sheila has to figure out, what kind of person is Senator Flake? What do he and the wastebook writers value?

SHEILA PATEK: I think that that they fall on the end of the spectrum that science should be done to solve human problems. That's— that's what I really spent a lot of time thinking about is, the real, tangible justification that someone like Senator Flake could listen to and could understand.

ANNIE MINOFF: That’s assuming he even showed. Sheila’d been told, somebody from Senator Flake’s office would come to the event.

SHEILA PATEK: I was expecting, you know, some kind of staffer.

ANNIE MINOFF: The intern!

SHEILA PATEK: Yeah the intern, right? And so I'm sitting there talking to somebody. And I look up towards the entrance and I see Senator Flake who's actually quite a distinctive looking person.

ANNIE MINOFF: Senator Flake is tall, tan. Got a beaming smile and a dimpled chin.

SHEILA PATEK: And I—<<laughing>> I mean I almost passed out! I FREAKED OUT. And whoever I was talking to who actually had some stature of their own, was like, “Are you OK? What's wrong?” And you know, I mean, I'm not like, Senator Flake's just another human per— you know, human being. I wasn't actually AFRAID of him. It was just that through this whole process this NAME you know, disembodied from this person had sort of loomed so large that to actually see him walking in the room really freaked me out!

ANNIE MINOFF: It's like, he exists!

SHEILA PATEK: Yeah! So I'm like— I’m trying to get myself back to the present to talking to the person who I was presenting to. And I see him, sloooowly weaving his way towards me. So yeah, so gradually he made his way to my station.

ANNIE MINOFF: What’d you say? Like what happened?

SHEILA PATEK: Well he came up and was very polite. And I said, you know, “May I present to you the work?” And he said sure….

ELAH FEDER: And here’s what Sheila told him. These shrimp? These “fight club” mantis shrimp? They are clobbering us when it comes to engineering. Outperforming our best systems by orders of magnitude.

ANNIE MINOFF: So first, these shrimp? They wield their hammers at accelerations on par with a bullet coming out of a gun, at accelerations that outpace missiles and racecars. And they don’t use combustion. Just this system of springs and latches in their arm. A system that they deploy over, and over, and over, without it breaking. And they do this in WATER. At tiny scales that human engineers can’t replicate.

SHEILA PATEK: So I started by just by showing him what engineering is not doing today, and what biology has been doing for millions of years.

ELAH FEDER: And then she really sells it. She explains what this could do for humans.

ANNIE MINOFF: She explained how mantis shrimp, even though they’re wielding their deadly hammers at bullet like accelerations, they avoid this weird fluid dynamics thing called cavitation. Usually when you’re moving as fast as a mantis shrimp does underwater you create this area of low pressure. And the water literally vaporizes in that spot. It forms a little bubble called a cavitation bubble. And this bubble implodes. In a burst of light, creating heat equivalent to the surface of the sun. Cavitation will wear away the steel on a boat propeller. It’s the bane of naval engineers. But mantis shrimp avoid it until the final moment when their hammer HITS that snail shell, and that shell cracks in a burst of heat and light. How do they do it?

ELAH FEDER: Or take the tail plate that these shrimp use in fights. This tail plate is taking blows like a punching bag, over and over. But unlike a punching bag, it’s LIGHT. That’s why engineers are actually using this mantis shrimp research to develop better materials for sports helmets, or for better armor.

SHEILA PATEK: And you know, I have to say, you know I guess we all know this. That a lot of times it really helps to have a conversation face-to-face with people. <<Laughs>> I mean, I think we all know that but it's good to be reminded. And he, you know he really, I really felt like he was listening or else he was a good faker. But I think he was listening!

ELAH FEDER: So Sheila goes for it.

SHEILA PATEK: And I said, you know is any of this worthwhile to you?

ANNIE MINOFF: And he pointed to the part of her poster about human applications.

SHEILA PATEK: And he said that that seemed worthwhile to him.

ELAH FEDER: But here’s the thing. Senator Flake— he wants these human applications. But if he wants this particular human application, this bio-inspired armor? You only get that if you gamble in the first place that investigating an animal as weird as the mantis shrimp might pay off.

ANNIE MINOFF: Because what we’ve found out about the mantis shrimp? We didn’t find it out because some scientist was looking for a human application. We know it because Sheila got curious.

SHEILA PATEK: It took a scientist’s eye to go in and reach for new knowledge. How fast is that animal going? How much force is it producing? Is that really a cavitation bubble collapsing to help break open the snail shell?

ELAH FEDER: This was one of Sheila’s main points. If you want applications, you’re gonna have to invest in curiosity too.

ANNIE MINOFF: And we are. The federal government puts something like 34 billion dollars a year into basic research. So it is totally fair to ask: What kind of return are we getting on that investment? Like what is the number?

PAULA STEPHAN: I think it would be very dangerous for economists to tell you that there's a number.

ANNIE MINOFF: That’s Paula Stephan, Professor of economics at Georgia State University, who could not give us a number.

ELAH FEDER: Paula’s like, “Look. You want a rate of return?”

PAULA STEPHAN: You’ve got to know what the benefits are. And you also have to know what the cost is.

ANNIE MINOFF: And for something like a stock market investment, that’s not too hard to figure out. But figuring that out for science?

ELAH FEDER: Yeah. Good luck.

PAULA STEPHAN: I mean the perfect example that everyone in my field brings up is the atomic clock. <<ticking clock>>

ELAH FEDER: In 1879, a guy named Lord Kelvin writes that maybe we could use atoms to tell time!

ANNIE MINOFF: Genius!

ELAH FEDER: But it takes about 7 decades before a physicist named Rabi actually figures out how to do it.

ANNIE MINOFF: And voila! The atomic clock.

PAULA STEPHAN: You know, most people, I think, who turn on their GPS device don't have a clue that we would not have GPS if it weren't for the atomic clock.

ELAH FEDER: This becomes a problem because if we want to calculate how much money went into the invention of GPS—

ANNIE MINOFF: Like a truly transformative technology—

ELAH FEDER: Do I have to go all the way back to Lord Kelvin?

ANNIE MINOFF: Or you can take Sheila’s research. So a decade ago, a materials scientist named David Kisailus he takes a look at Sheila’s research, thinks “What the heck is that shrimp hammer made out of?” He spends 5 years finding out, and last fall, David got a patent. For a mantis shrimp-inspired material he says is fifty percent more damage resistant than what Boeing is using in its 787 airplane. And he wants to sell it to companies like Airbus.

ELAH FEDER: And if he succeeds, Sheila’s research becomes another one of these success stories. It becomes an example that science advocates can cite, whenever a new wastebook comes out. They can point to this and say, “Hey look, investing in curiosity? That can pay off big.”

ANNIE MINOFF: Just like it did with the MRI, the laser, and—oh yeah—the internet.

ELAH FEDER: Right, the internet. Good one.

PAULA STEPHAN: Well it's very tempting to give all those examples and I've given you some examples today.

ANNIE MINOFF: Paula again. Paula says, beware the anecdotes!

PAULA STEPHAN: The problem though with those studies is that they've just been selected on winners, you know? And there are number of research projects out there that don't have a happy ever after ending so to speak.

ANNIE MINOFF: So….no. There’s is never gonna be one magic number that scientists and politicians can all point to and say, yeah that is the value of science. This is how much we should spend.

ELAH FEDER: Right, which means these funding debates end up playing out in politics. And they’re about what you value. You know how much do much do you value the search for new cures? Or understanding the structure of space-time? Or growing the GDP? That’s why budgeting is hard.

ANNIE MINOFF: Because we all have our own answers to those questions. Including Sheila.

ANNIE MINOFF: Why does Sheila Patek value science?

SHEILA PATEK: You know the answer to this question has been a journey. Because it has actually taken me most of my career to have the confidence to say this. That the knowledge that we generate in my lab is why it's important. It's that we have explored biology. We have tested it. We have, we have put it to the most rigorous scientific analysis that we possibly can. And from that we have been able to say new things about the world. And that is what I think the value of what I do is.

ANNIE MINOFF: A month after their conversation, Senator Flake released another waste book. It’s science-themed. Titled, 20 Questions: Government Studies That Will Leave You Scratching Your Head.

ELAH FEDER: The cover features the latest poster children of wasteful science spending. No boxing shrimp, But there’s a drunk songbird and a sexy goldfish.

ANNIE MINOFF: But inside, the writers do something interesting. They have a list: 20 questions that they hope will guide science funding decisions. Questions designed to get at what the value of science is. Will this research advance science in a meaningful way? Will the study enhance technology? Or advance medicine?

ELAH FEDER: Will it expand our understanding of the universe?

ANNIE MINOFF: They’re good questions. They’re continuing the conversation.

ELAH FEDER: And then you flip the page. And you read about how one researcher spent part of a 1 MILLION dollar grant to find out where it hurts most to get stung by a bee.

ANNIE MINOFF: And another round of the dance begins.

***********

ANNIE MINOFF: Undiscovered is reported and produced by me, Annie Minoff.

ELAH FEDER: And me, Elah Feder. Our editor is Christopher Intagliata. Thanks also to Danielle Dana, Christian Skotte, and Brandon Echter.

ANNIE MINOFF: Shrimp sounds were recorded by Leah Fitchett and Martha Munoz. We had fact-checking help from Michelle Harris. Original music by Daniel Peterschmidt. I am Robot and Proud wrote our theme.

ELAH FEDER: Special thanks to our launch partner, the John Templeton Foundation. You can find more Undiscovered at undiscovered podcast dot org or on Twitter at undiscoveredpod.

ANNIE MINOFF: And a tip of the hat to everybody who reviewed us on Apple podcasts. Thank you to Rockstein, Jeeves, Elah’s mom. It helps us out and we really appreciate it.

ELAH FEDER: Thanks mom. See you next week!