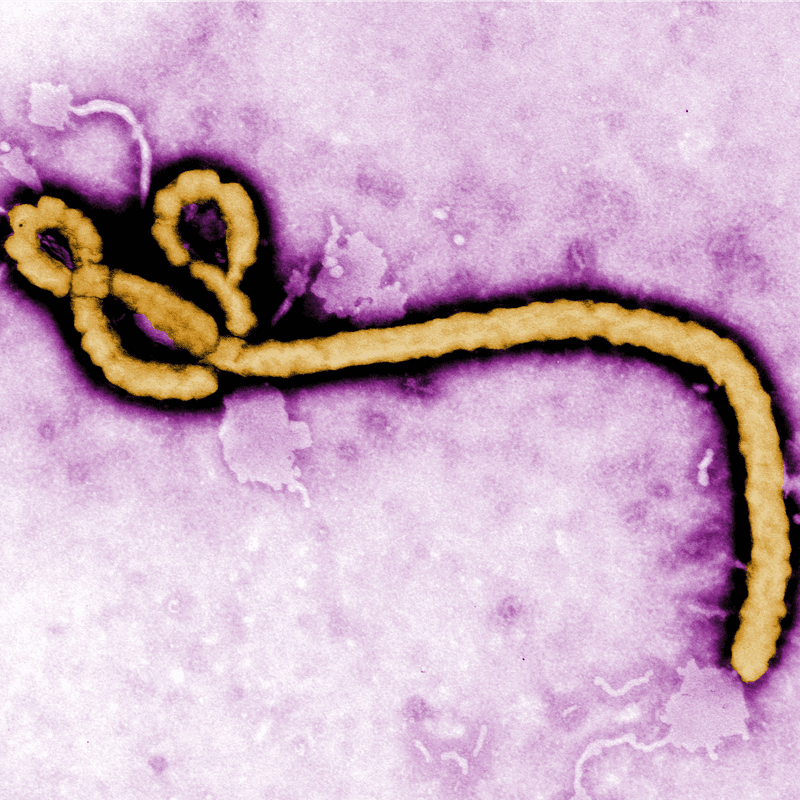

BROOKE: As we watch the struggle to contain the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, the images from Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone look hauntingly familiar. Because they are. They are reflections of what author and professor Priscilla Wald calls “the outbreak narrative.” That’s what we see when we hear the word Ebola...

Newscast 1: Some of this looks like scenes out of a movie, of course. And there are questions about Ebola...

Newscast 2: It's more reminiscent of a movie than it is reality. How has this spiraled out of control so quickly?

Newscast 3: Our brains have evolved over time to consider the threats we can see and we’ve all seen the images coming from the movies...

BROOKE: It’s based on truth, but highly sensationalized, as in Richard Preston’s 1994 bestseller The Hot Zone. Here, he follows the path of an Ebola-like virus carried by a man called Charles Monet...

A hot virus from the rain forest lives within a 24-hour plane flight from every city on earth. All of the earth’s cities are connected by a web of airline routes. Once a virus hits the net, it can shoot anywhere in a day. Wherever planes fly. Charles Monet and the life form inside him had entered the net.

BROOKE: From there, it’s just a quick leap to a terrified Tinseltown. Take the movie Outbreak from 1995…

If one of them’s got it, then 10 of them have got it now, and if one of them gets out of Cedar Creek, we have a very interesting problem

Or 2011’s Contagion…

On day one, there were two people, then four, then sixteen. In three months it’s a billion - that’s where we’re heading!”

Priscilla Wald, author of Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative explains the moment this particular variant of the narrative began...

WALD: The beginning of what I’m calling the outbreak narrative, this specific narrative about a hemorrhagic fever, about disease emergence, is 1989. And that was a conference sponsored by Rockefeller University and others where a group of scientists of and epidemiologists and one medical historian got together to consider the problem of what they then defined as disease emergence.

BROOKE: What sparked it?

WALD: What sparked it was HIV. And I think the reason that this was so significant was that in the late '70s with the last naturally occurring case of smallpox - with the eradication of that - there was sanguinity. It was like, "Look at how we've advanced. look at the progress we've made. infectious disease is going to become a thing of the past." Ebola had appeared in the mid-70s. Bolivian hemorrhagic fever. Hantavirus. But they were relatively well contained. And then we encountered HIV/AIDS. which was something that medical science couldn't understand, couldn't contain. Truly a pandemic.

BROOKE: So how did this narrative emergence from this conference.

WALD: This group of scientists and doctors and so on - said the problem here is development. That human beings were moving into places they've never been before and they're encountering these microbes to which they are not immune. This is not just a medical problem - it's a social problem, it's a social problem and then their analysis of that problem got picked up by science writers, the mainstream media and popular fiction and film.

BROOKE: So what is the basic plot of the modern outbreak narrative.

WALD: A new microbe is encountered and creates a new disease, something that liquefies organs and makes blood come out of all the orifices and it happens in a jungle somewhere and it quickly gets into the cities of the global world. And it becomes a species threatening event. Ultimately it is contained by modern science and medicine. The solution always comes from the US, the problem always comes from - occasionally Asia - but almost always Africa. One of the features of an outbreak narrative is that it ends. That there is a resolution and it's not as horrific and apocalyptic as everybody feared. Now with Ebola there's not a cure but traditionally the Ebola outbreak is extremely dramatic but very quickly contained. I am still hopeful that now that we have paid attention Ebola is certainly something to be respected we, the world, will get it under control.

BROOKE: So Ebola is a perfect candidate for this narrative and there are a lot of upsides. But ultimately there is a substantial downside.

WALD: The outbreak narrative creates the possibility for stigmatizing of people as well as places which has economic consequences and social consequences. It can make people do things that actually exacerbate the danger.

BROOKE: Like?

WALD: Being afraid to go to the emergency room when they're sick. You see that happening in Africa. A second problem is that it can make people complacent. Everyone is so used to Ebola being quickly contained that this one was allowed to get out hand. But to me the deepest problem of the outbreak narrative is that it perpetuates a crisis mentality. What we immediately go to is containment - thinking about pharmaceuticals and vaccines. But the greatest single vector to turn an outbreak into an epidemic is poverty. And when you see people living malnourished, not having adequate shelter, not having access to state-of-the art healthcare, those are the things that really turn an outbreak into an epidemic and an epidemic into a pandemic. So my question is why aren't we looking at the deeper problem and I think the crisis mentality of the outbreak narrative is a contributing factor.

BROOKE: Ok I'm going to stipulate that we are wired for narratives. The world is too complicated to understand as data sets. We create stories. So, how would you change this one?

WALD: An outbreak narrative that would begin to get us being to to address the problem would start before the first outbreak. And I'll give you a real life example with thanks to Paul Farmer, medical doctor and anthropologist. Ten years before an outbreak in an impoverished section of Haiti corporate issues in the United States and Haiti got together and built the Peligre Dam. As a result a once-thriving subsistence farming community is now underwater. The farmers have had to move up the mountain where the land isn't arable. They have then moved from a sustainable lifestyle into poverty. It's a place that people talk about as disease-ridden and crime-ridden. Now we have the conditions for what we think of as the outbreak narrative. But we're telling the story very differently and now we know where to begin to address the problem.

BROOKE: So at what point are we in the outbreak narrative. Would you see we're in the heroic struggle?

WALD: We are in the heroic struggle of the outbreak narrative. Witness the headlines. Words like apocalypse. CNN's comparison of Ebola to ISIS. As though ISIS is a bioterrorist itself. That's the evidence of an outbreak narrative.

BROOKE: Priscilla thank you very much.

WALD: Thank you.

WALD: Priscilla Wald is professor of English and Women's studies at Duke University and author of Contagious:Cultures, Carriers and the Outbreak Narrative.