4. Vieques and the Promise To Build Back Better

Alana Casanova-Burgess: 13 days after Maria, a group of people affected by the hurricane, met at the Calvary chapel. That's a church in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico.

Donald Trump: There's a lot of love in this room, a lot of love in this room.

Alana: President Trump was there visiting the Island to assess the hurricane damage. He stopped at the church and it was in that visit that he did something a lot of Puerto Ricans will never forget. He started throwing rolls of paper towels towards the hurricane victims.

Donald Trump: Great people.

Alana: It was, let's say, a controversial act.

Male speaker from Morning Joe: Throwing paper towels at the victims of the hurricane like it was a game. I've never seen anything like that before.

Female speaker from Morning Joe: Ever.

Male speaker from Young Turks: You were supposed to be helping victims of a hurricane. So he's like, "There's a lot of love for me here, right? I threw paper towels and people. People loved it."

Nydia Velazquez: To kick fellow citizens when they are down is shameful.

Alana: At the time, thousands were homeless and millions were without electricity. It was an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. And for many, this act by the president was deeply offensive.

Male reporter from ABC News: Mr. Trump also appeared to criticize the US territory for there more than $70 billion debt.

Donald Trump: I hate to tell you Puerto Rico, but you've thrown our budget a little out of whack.

Alana: The president made these kinds of remarks in public, but in private, his advisors were having meetings with then-Governor Ricardo Rosselló Nevares and his team.

Carlos Mercader: [Spanish language]

Alana: This is Carlos Mercader, former director of the Puerto Rico, federal affairs administration in Washington. In other words, he was Rosselló's point man on Capitol Hill. Mercader says that the day after Trump's visit to the church, the governor's team was summoned to the White House. He says they were brought to the Situation Room-

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Alana: -kind of bunker in the west wing, where military decisions are made and crises are dealt with. Vice president Mike Pence, was at the head of the table, surrounded by various FEMA representatives, all looking at maps of Puerto Rico.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Alana: "The atmosphere was tense," Mercader said, because the FEMA administrator was defending the hurricane response and the governor told him in front of the vice president, that what they were doing was failing. Later, Rosselló's team met with more heads of federal agencies. It was during this meeting that something unexpected happened. The director of the office of management and budget at that time, Mick Mulvaney, told them that president Trump wanted to meet in person.

Carlos: "Governor and Carlos." [Spanish language]

Alana: Without knowing what to expect, they were shuffled directly into the Oval Office. Mercader says they actually bumped about five or seven other federal agency heads that were waiting to meet with Trump. The president entered the room, the governor and his staff thought this would maybe just be a photo op, something quick.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Alana: Then Trump told the governor, "You know what? I want to do a press conference with you."

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Alana: It was a total surprise, something that was never on the agenda. In fact, the administration had told them that Trump was too busy to meet.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Alana: The president, got out of his chair and walked to a cabinet-

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Alana: -Filled with cans of aerosol hairspray.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Alana: He sprayed his hair and with a very serious demeanor, looked back at Mercader and said,-

Donald Trump: Carlos, you go there.

Alana: The White House press corps then filled the room.

Donald Trump: Thank you very much. It's great to have the governor of Puerto Rico with us. We have gotten to know each other extremely well over the last couple of weeks and I can tell you, you are a hard working governor. It's a tough situation. So much has to be rebuilt. Even from before. With that being said, I think we've done a really great job-

Alana: In the recording, you can see- governor caught between making the president feel comfortable and the need to communicate the dire situation in Puerto Rico.

Ricardo: Thank you Mr President. Thank you for setting this opportunity. It's a catastrophic situation in Puerto Rico as you know but certainly working in a united front we are going to beat this. We know we're going to build better than before. Today, it's an example. Mr President, I don't think--

Alana: An example. That's how Rosselló described the work that his government was undergoing alongside Trump's administration. An example of working together to rebuild Puerto Rico. Build back better. That was the slogan of the promise to reconstruction.

[music]

Alana: From WNYC and Futuro Studios, this is La Brega. I'm Alana Casanova-Burgess and in this episode, the historic agreement that was supposed to help the island's reconstruction after Hurricane Maria. Supposed to.

[music]

Alana: When it comes to so many things, Puerto Rico is the exception to the rule, including with federal responses to natural disasters. This is how it's supposed to work. A massive fire engulfs California, a huge hurricane strikes Texas, and another one makes landfall in Florida and one of the first federal agencies to respond is FEMA.

Brock Long: If you start with Harvey all the way over to the California wildfires, over 25 million Americans have been impacted. The FEMA search and rescue teams alone saved over 9,000 lives. Tens of thousands of lives have been saved. Over 4.5 million Americans have been registered inside FEMA's individual assistance program.

Alana: FEMA's ability to provide aid comes from something called the Stafford Act. The letter of the law in this Act is clear. FEMA has the duty to rebuild but only up to the way things were before a disaster. FEMA cannot make destroyed buildings better than they were before except in rare instances. Today's story is about one of those exceptions. Cristina del Mar Quiles from al Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, the Center for Investigative Journalism in San Juan, has been covering Puerto Rico's rebuilding efforts for more than two years and she takes the story from here.

Cristina del Mar Quiles: After the impromptu press conference with Trump, the surprise engagements from the White House kept coming for the Puerto Rican team.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Carlos Mercader recalls a lunch on the White House mezzanine where Tom Bossert, Trump's homeland security advisor, showed up.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: He had a handwritten document with some scribbled notes and ideas about Section 428 of the Stafford Act. This was a defining moment for the recovery of the island. Section 428 is a very specific part of the Stafford Act that grants FEMA the power to go beyond the norm when it comes to reconstruction after natural disasters. The document offered Rosselló help rebuilding everything that was damaged on the island and went even further and proposed building new and improved infrastructure.

For example, if a building had only lost some of its windows, Section 428 made it possible to replace all of them. The idea was that the affected structure would be rebuilt better than before. With Section 428, the federal government was promising stronger and more resilient construction.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: "Puerto Rico would receive more money in a shorter period of time," Trump's people said at the lunch. Section 428 had been used before but in really isolated cases like the reconstruction of New York's lower Manhattan subway station and New Jersey's energy plant back when Hurricane Sandy hit the East Coast in 2012. The plan Bossert had for Puerto Rico was using Section 428 for the whole island's reconstruction, the most expensive use of the Section up to that point.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: But Puerto Rico had to ask for it first. The governor had to make a formal petition based solely on that handwritten piece of paper given to him by Bossert and he had to do it right then and there. It was a tempting offer. Any politician would prefer to end their term with brand new infrastructure, better than the one they came into power with, but there was a catch in Section 428.

The local government would be responsible for any unforeseen expenses during construction. Puerto Rico was a jurisdiction in the middle of a financial crisis. In simple terms, Puerto Rico did not have the means to deal with those unforeseen expenses.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

[music]

Cristina: Mercader says the governor told Bossert that he was open to the idea, but it needed more discussion.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Mercader remembers it as a constant struggle. Meeting after meeting of a heated debate about what would be best for Puerto Rico. One of the main pieces of contention was the timeframe FEMA would allow the government of Puerto Rico to inspect and describe the damage. FEMA basically functions as an insurance company that evaluates and then approves money for reconstruction, but they're always trying to spend as little as possible.

In practice, FEMA wanted to use the 428 to build back better, but with as little investment as possible on their part, while the Puerto Rican government was trying to secure enough money to actually get the projects done. All parties had to reach an agreement on every single project following an island-wide disaster. That, obviously, was going to take some time. The proposal from the federal government was that all agreements would be due in 12 months. At that moment there were 5,000 projects pending for review. The schools, community centers, parks, roads and public buildings. The total amount to make these projects happen, $30 billion.

A few weeks after the intense meetings at The White House, Carlos Mercader remembers traveling back to Washington with Governor Rosselló to attend meetings unrelated to 428. In one of those meetings, Elaine Duke, Acting Secretary of Homeland Security, bust into the room with another piece of paper.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: And told the governor, "Sign this."

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: It was a formal printed letter to be signed by Rosselló asking for authorization from the federal government to implement section 428 for all of Puerto Rico. Mercader says she was very insistent.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Telling the governor they had waited too long and that this had to be done now. The governor told her,-

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: "Look, I cannot do it this way."

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: "What's the problem? What's missing?" she asked. Rosselló responded,

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: "We need to discuss it because you haven't agreed to anything we have proposed. To be honest, we have reservations." The most important reservation was the process. For each reconstruction project, they had to navigate a sea of red tape at both local and federal levels. While Rosselló evaluated if section 428 was really worth it, the conversation with federal staff had become more difficult, especially when talking about the amount of money around the reconstruction.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Mercader says that every time Trump's cabinet talked about money, he felt they had a grudge about it.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Mercader felt their tone was condescending at times. Some, like Mick Mulvaney, who would eventually become Trump's chief of staff and had been appointed to be the captain of this effort, took it even further, acting despotic at times.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

[music]

Cristina: Our podcast team reached out to Bossert, Mulvaney, Duke, and Brock Long, who was famous administrator during the 428 negotiations. Only Long responded to our request and told us he was not available. During all these harsh negotiations, Rosselló came to a conclusion.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: He would formally request 428 because it was evident that it was the only way the federal government was willing to work with Puerto Rico.

Cristina: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Instead of 12 months, Rosselló's team got the federal government to give them 18 months to evaluate all 5,000 products. That's how Governor Rosselló finally accepted and officially asked for Section 428 to be applied to Puerto Rico. It was actually the only option on the table but Rosselló and his team went back to Puerto Rico to announce the implementation of Section 428 as a resounding victory of his administration.

Ricardo Rosselló: [Spanish language]

Cristina: At a press conference, he spoke about the important achievements they reached in a span of 48 hours.

Rosselló: [Spanish language]

Cristina: He explains they made a series of requests to the federal government and then mentions a quote, 'novel mechanism, Section 428.'

Rosselló: [Spanish language]

Cristina: He then describes how 428 allows the government to take all bigger building projects and add them all together. He says this gives more flexibility to move estimates around. This wasn't the only time he praised Section 428. The audio quality isn't very good but here, he's speaking to the Puerto Rico Builders Association.

Rosselló: [Spanish language]

Cristina: In this 2017 speech, you can hear how Rosselló talks glowingly about the prospect of rebuilding Puerto Rico with a new set of tools.

Rosselló: [Spanish language]

Cristina: He asked everyone to grab this opportunity by the horns and make a better, more robust, and resilient Puerto Rico.

Rosselló: [Spanish language]

Cristina: I admit this is a little puzzling after hearing Mercader explain how much pressure Washington put on the governor to accept 428. So I asked him why, despite all the troubles he had just described, they presented these as an achievement of their administration.

Mercader: [Spanish language]

Cristina: "Because the written agreement stated this would be a faster process than a normal one," he said. But the Puerto Rican government knew that Section 428 was not risk-free, and it was a massive undertaking.

[music]

Cristina: Even months after the hurricane, the situation was dire for a lot of Puerto Ricans and neither FEMA nor the local government had a clear idea of how, in practice, they would really build back better.

News 1: Basic supplies like food, water, and medicine still scarce in some areas forcing many families to improvise their holiday celebrations.

News 2: Every school in the island has dealing with the same situation, losing students, losing people, losing family.

CNN: Half of the island did not have electricity at the end of 2017 three months after the storm.

News 3: Inside the medical crisis in Puerto Rico, tomorrow marks one year since Hurricane Maria devastated the island.

News 4: Right now, people are traveling hours to get the help they need.

Omar Marrero: [Spanish language]

[music]

Cristina: That last voice is Omar Marrero, a former director of the office that is in charge of the recovery efforts in Puerto Rico. I interviewed him in February 2019, and he told me that even a year after the approval of Section 428, there wasn't a single project greenlit, not even an agreement on a fixed cost estimate for any of the rebuilding projects.

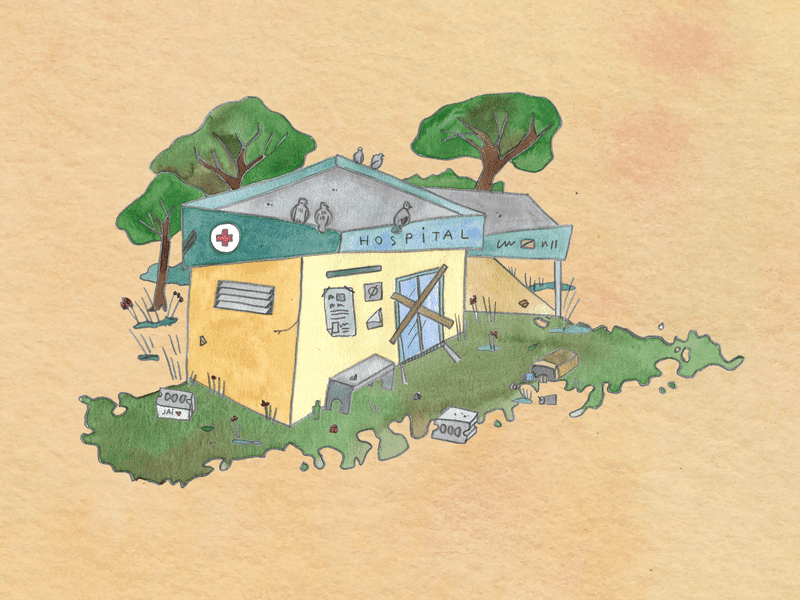

Without those agreements, not a single one of these projects could get started. These delays seriously affected one of the most important projects of the promised rebuilding, the hospital on Vieques Island. A project that had been in planning since Hurricane Maria hit the island and which they even referred to as an early project; a brand-new hospital for the 9,000 residents of this island municipality.

[music]

Alana: The delay on this project will end up having dire consequences. When we return, what happened in Vieques. We'll be right back.

[music]

Alana: We're back to La Brega.

Diana Ramos: [Spanish language]

Alana: This is Diana Ramos, a producer who lives on the island of Vieques. Here she describes how hard it is to reach what was the Central de Diagnosticoy Tratamiento Susana Centeno, the only health center with an emergency room on Vieques.

Diana: [Spanish language]

Alana: She says some of the electric poles are still bent over almost horizontally, and the area around the center is overgrown with vegetation.

Diana: [Spanish language]

Alana: This was in October of 2020, more than three years after Hurricane Maria hit Vieques and the rest of Puerto Rico, and this was the first project of the build back better plan under Section 428 of the Stafford Act.

Christina Delmarquiles from El Centro de Periodismo[Spanish language] continues from here.

Christina: Vieques, La Isla Nena is a place that is deemed by many as the colony of the colony. It's an island haunted by a long history of negligence and abuse by both the Puerto Rican government and the federal government. To understand the impact of 428 in Vieques, one has to first understand the long struggle of this community for better health services.

ZaidaTorres: [Spanish language]

Cristina: This is Zaida Torres. She says that Vieques has never existed for the Puerto Rican Department of Health. Torres is now a retired nurse. She knows the history of the island's health services because she spent her entire career serving in the only hospital in Vieques. This health center is crucial since the nearest hospital is an hour and a half away by boat or a 30 minute flight.

Getting on a plane is not cheap either, and in reality is inaccessible to most of Vieques population. Most people have to use what has been for decades, an inconsistent ferry system. Sadly, Zaida also a veteran to this commute. She's a cancer patient who has to travel every 21 days to La Isla Grande, the big island, to get the treatment she needs.

Zaida: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Often, the ferry is not available for one reason or another and she has to call to cancel her appointment. We're not even mentioning the days where she can travel and how difficult it is for her to actually get back home.

Torres: [Spanish language]

Cristina: She says that at least two times she has had to wait for the 8 PM Ferry because the procedure took longer than expected.

Torres: [Spanish language]

Cristina: She waited until 8 PM, no ferry. Then waited for the 9:30 PM ride, still no ferry. Her return trip after a day where she underwent chemotherapy started at midnight.

Torres: [Spanish language]

Cristina: "As a cancer patient it's the worst thing that can happen to you," she says. Zaida is not alone in this. Scientific studies have shown that Viequenses have higher cancer rates, as well as very high occurrences of diabetes, hypertension, lupus and asthma when compared to the Big Island.

Torres: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Zaida asks herself why this is.

Periscope Films: This is a beach of Vieques island near Puerto Rico in the Caribbean Sea. Peaceful isn't it? White sand, palm trees and the intensely blue water of the tropics.

Cristina: The answer can be found in films like these, an industrial documentary from the '50s commissioned by the United States Navy.

Periscope Films: But one day ships of the Atlantic Fleet came from the west, and slipping across the long horizon at dawn, commenced to hurl steel and explosives against this strip of sand.

Cristina: For more than six decades, most of Vieques island was used by the US Navy and their allies as an open range where they conducted war games with live ammunition and real explosives.

[chanting]

Cristina: During those decades of constant bombing, various groups in Vieques and Puerto Rico demanded that the US Navy leave Vieques. Then on April 19th, 1999.

Telemundo 1: [Spanish language]

[music]

Cristina: David Sanes was a Viequenses employed as a security guard in an observation post inside the range where the Navy practiced its war games. Two 500 pound bombs hit the observation deck where he patroled killing him immediately. His family heard the explosions and were kept in the dark about what happened for at least a whole day. This death sparked a civil disobedience movement, Viequenses, Puerto Ricans from the main island, diasporic groups and US activists and politicians rallied. They traveled to the military practice range, entered the area, and waited for the federal authorities to arrest them.

Protestor: Go home. This is Puerto Rican land.

The News Hour: First tonight, the Vieques showdown. Activists on Puerto Rico's Vieques island continue to wait today for a possible federal raid.

Protestors: [Spanish language]

John Warner: What steps have you taken then to enforce the law?

Pedro Rosselló: It's a federal law. Sometimes it is not wise to act. All I'm saying is I'm giving you what I think is good advice.

James Inhofe: Someone's going to die doing that. That blood will be on your hands.

Pedro Rosselló: Somebody has already died, Mr. Senator. One has died. [crosstalk] If the bombings continue that blood will be on your conscience.

Speaker 8: Thank you very much. We opened this hearing. Don't push it.

Cristina: At the end, they actually made it happen.

George W. Bush: My attitude is that the navy ought to find somewhere else to conduct its exercises. These are our friends and neighbors and they don't want us there.

Cristina: In 2001, President George W. Bush announced that the US Navy would leave Vieques in 2003, but the legacy of the bombings continues today. A group of Viequenses sued the federal government asking them to acknowledge the environmental harm caused by decades of war games and the contamination of land and sea. Even with a federally mandated clean-up, there are at least 10 years of work left.

All this is the setting when on the night of September 19th, 2017, Hurricane Maria made landfall in Vieques with sustained winds of 100 miles per hour. The devastation continued until late afternoon the next day disrupting the fragile calm of the island.

Amaya Cruz Ventura: [Spanish language]

[music]

Cristina: This is Amaya Cruz Ventura, a 14-year-old who was born and raised in Vieques. She says everything was in ruins after the hurricane.

Amaya: [Spanish language]

Cristina: She was shocked. In just one hour, everything changed. Amaya, spent the hurricane huddled with her family in their home. She recalls how the situation of the island's health center following the hurricane left an impact on her.

Amaya: [Spanish language]

Cristina: It was completely destroyed.

Amaya: [Spanish language]

Cristina: The roof seemed to be gone.

Amaya: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Amaya says that at that moment, she thought that since health is a top priority, someone would eventually fix the hospital. It seemed at first like that would happen. Omar Marrero who was the director of the Recovery Reconstruction and Resiliency Central Office known as COR3, said that rebuilding this medical facility as a proper hospital would be the first project to benefit from section 428. It would be an early project. As early as 2018, they actually reached an agreement to start building a new hospital for $22 million. Just eight months later, FEMA started changing the initial cost estimates.

Omar Marrero: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Marrero explains that they changed the cost to $50 million and then to 70 million. He remember saying to FEMA, that 70 million for a hospital for 7000 people was going to be a tremendous hospital.

Carlos: [Spanish language]

Cristina: In other words, he was implying that maybe that was too much money for a hospital for Vieques. Then, one day, FEMA changed it's mind and started talking about just repairing the facility instead of rebuilding an improved version. What the Puerto Rican government originally feared about 428 came true. It was not easy to reach a working agreement with FEMA.

Marrero, then had to testify to different committees in Washington investigating the reconstruction of Puerto Rico. In June 2019, a year after the announcement that the hospital in Vieques would be the first project under Section 428, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, asked Marrero the following question.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez: Mr. Marrero, are their patients in Puerto Rico still receiving medical care in temporary facilities?

Marrero: Yes, ma'am, Vieques Island.

Cristina: During all this time, Viequenses were using a makeshift health facility covered by tarps. When those were deemed inadequate for prolonged services, it was moved to an old building near the destroyed facility as they waited for the new construction and a more resilient hospital.

Alexandria: Why has it taken so long to rebuild these facilities?

Marrero: The process. I don't know if you're familiar, but in Puerto Rico we're implemented for the first time in FEMA history, what is called section 428. To add the fact that Section 428 is a pilot program. There's no clear guidance in writings.

Cristina: Then Marrero gave an explanation of what section 428 had meant for Puerto Rico repeating a metaphor they had used before.

Marrero: We're essentially designing the plane as we fly.

Cristina: Designing a plane as it flew. While the federal and Puerto Rican government figure out how to advance the recovery efforts, back in Vieques, residents were dealing in any way they could with their health issues.

Jessica Ventura Perez: [Spanish language]

Cristina: That is Jessica Ventura Perez. Jessica, is Amaya's aunt. Jessica says she has always correlated the chronic asthma of her second daughter, Jaideliz with environmental issues that exist in Vieques. Even before the hurricane she was one of the Viequenses that preferred to schedule appointments outside of Vieques, due to a lack of quality service on the island.

In January of 2020, she noticed that her daughter, Jadeliz was not feeling well. She had a constant cough and felt discomfort and pain in her body. Jessica took her to one of the specialized pediatric hospitals in San Juan to get her examined.

Jessica: [Spanish language]

Cristina: She noticed that Jaideliz looked out of it, not her normal self. The next day they got back to Vieques and Jaideliz was looking better. They spent the afternoon with some friends on their patio, and then around 11:30 PM they went to sleep. But at midnight-

Jessica: [Spanish language]

Cristina: -Jaideliz entered Jessica's room in tremendous pain. She was holding her head and told Jessica that she had a terrible headache. Jessica sat Jadeliz in her bed. At that moment her teenage daughter started having a seizure. Jessica started screaming for help, while taking her daughter to the car. One of Jessica's neighbors heard her and helped carry Jadeliz. They headed to the provisional health facility in Vieques. Jessica remembers vividly how when they arrived with her daughter having a violent seizure, she asked the doctor what he thought could be happening. He responded-

Jessica: [Spanish language]

Cristina: "I see the same thing you see." "But you are the doctor and I am not," she snapped back. After an hour and a half of waiting the assigned pediatrician arrived at the provisional facilities.

Jessica: [Spanish language]

Cristina: He had arrived empty-handed, and he couldn't really do anything. He started making calls for an emergency helicopter to move Jaideliz to San Juan, but he told Jessica that that process was going to be a lengthy one. He then decides to charter a plane instead. They get Jaideliz in an ambulance to the airport in Vieques. When they arrive and take her out of the ambulance to get her in the plane-

Jessica: [Spanish language]

Cristina: -Jaideliz enters cardiac arrest.

Jessica: [Spanish language]

Cristina: They had to intubate her in the ambulance and rush back to the temporary facilities. When they arrived, Jessica and family members that joined notice that Jaideliz was not being connected to a ventilator to help her breathe.

Jessica: [Spanish language]

Cristina: They realized that the facility didn't have a mechanical ventilator on hand. They only had a manual respirator. Over the next hour, the medical personnel were exhausted from manually pumping the machine, keeping Jaideliz breathing. Three of Jaideliz and Jessica's family members volunteered to do it instead. For the next two hours, the paramedics and the family took turns to do what a machine was supposed to do.

Jessica: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Five hours after arriving at the provisional hospital, 13-year-old Jaideliz died. An autopsy later revealed that she had suffered from a cerebral aneurysm, a medical emergency that requires urgent action.

Hector Ventura: [Spanish language]

Cristina: That's Hector Ventura, Jessica's father, Jaideliz's grandfather, telling a local news channel that his granddaughter died because what can barely be called a hospital failed in giving her the emergency attention she deserved. Jaideliz's death shook Vieques as a whole. Family and neighbors, stormed the surrounding area of the provisional hospital to confront its director and hold her accountable for the teenager's death.

Protestors: [Spanish language]

Cristina: During Jaideliz memorial service, Geigel Juilio Rosa Cruz, a neighbor, asked everybody to join him in a special protest.

Geigel Juilio Rosa Cruz: [Spanish language]

Cristina: He asked for everyone to take a cinder block to Vieques public square, right in front of their mayor's office, and place them there at six in the morning. The next day, the public squared was filled with cinder blocks, a concrete display of their plea for the construction of a real hospital that could really give them dignified health services. Two days after the protest, a week after Jaideliz's death, FEMA announced a fixed cost estimate agreement for a new hospital for Vieques $39.5 million. It was the third time in three years that a new hospital for Vieques was announced.

Protestors: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Later, the cinder block protest moved to San Juan, in front of el Capitolio, the capital building. There Vieques demanded the start of the hospital's construction.

Protestors: [Spanish language]

Cristina: Then the pandemic started and nothing happened. In July, 2020, Peter Gaynor FEMA's director testified before Congress to explain why construction had not started. Congresswoman Nydia Velazquez confronted him.

Nydia Velazquez: With the COVID pandemic, what are we saying to the children and the elderly in Vieques, seven months after the money was approved? Why is that difficult to break grownd in Vieques, that we sent a message to the people of Vieques that their lives matter?

Peter Gaynor: Yes ma'am. Again, it doesn't happen overnight. There's design, there's environmental--

Cristina: Viequenses are still waiting while Jideliz's mom asks-

Jessica: [Spanish language]

Cristina: -how many more Jai's will happen while they wait for the construction of a hospital. It's impossible to say that the bureaucracy of section 428 cost Jaideliz's death. Even without all the delays it's improbable that a brand new hospital would have been ready for Jaideliz or many others that died during the three years that Vieques has gone without a proper hospital.

[music]

There is a history between Vieques and the United States, a sequence of events, formalities, red tape and protocols that are designed offices in the most important departments of the federal government, modified in agencies and altered by officials. When combined with negligence and neglect, this bureaucracy has deadly consequences for people like Jaideliz.

[music]

It is really impossible for me not to wonder that maybe with a little more support to start the construction of the hospital, more wood will, more commitment to build in that hospital back better, and have it equipped with the right tools for emergencies that perhaps Jaideliz's story would have been different. Could Jaideliz have been saved? We can not know. What I know is that it's terrible to have to live in a world where we have to ask ourselves that question.

Alana: Christina del Mar Quiles is a reporter for the Center for Investigative Journalism, Centro de Periodismo Investigativo. At the time of this recording, construction of the hospital in Vieques has not yet started. Between 2019 and 2020, the government of Puerto Rico renegotiated the implementation of section 428 to help advance some of the pending projects. There are 4,483 projects from hurricane Maria that still have to undergo this process and which still have no money allocated for them.

In January of 2021, a year after her death, Jaideliz's family sued the Puerto Rican government saying their civil and human rights were violated when officials failed to guarantee health services to properly tackle the medical emergency that took the 13 year old's life. Their claim co-signed by Jaideliz's aunt, her parents and grandparents asks the court to deem the abandonment of public health for Vieques as unconstitutional and a threat to human rights.

[music]

La Brega is a co-production of WNYC studios and Futuro Studios. This episode is available in Spanish as well and you can listen to either wherever you hear your podcasts through La Brega's podcast feed. This episode was a collaboration between La Brega and CPI, the Center for Investigative Reporting in Puerto Rico. It was produced by Ezequiel Rodríguez Andino with help from the Diana Ramos and from me. The story was edited by Luis Trelles and The English adaptation had additional editing by Marlon Bishop and Mark Pagan.

Fact checking by Istra Pacheco. Engineering is by Stephanie Lebow, Leah Shaw Damron and Alicia. Original music for La Brega was composed by Balloon and our theme song is by EFA. Art for this piece was done by Garvin Sierra. Deep gratitude to Vanessa Almenas, Lauro Marcuso, and Luis Valentinortis. Leadership support for La Brega is provided by the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation and the John S and James L. Knight Foundation, with additional support provided by Aimee Lees. Coming up in the next episode of La Brega, David and Goliath play basketball in Athens. [Spanish language]

Copyright © 2021 Futuro Media Group and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.