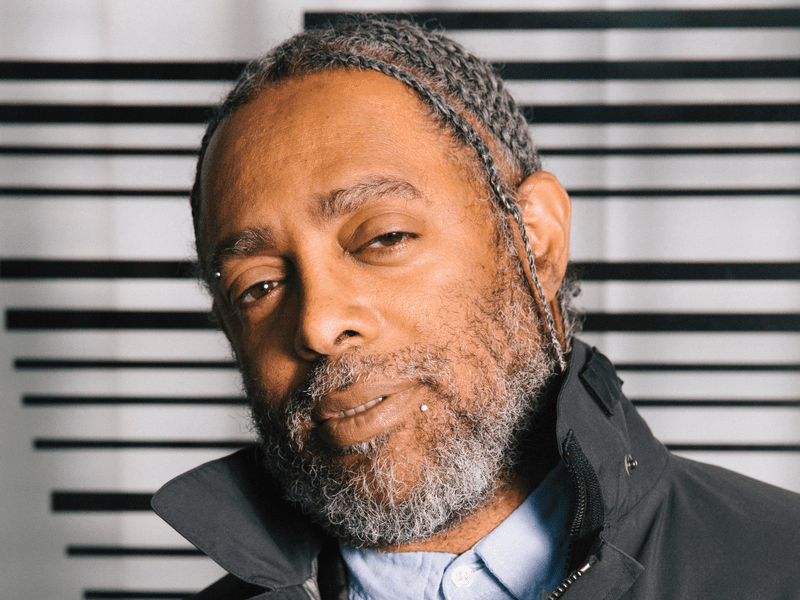

Video artist Arthur Jafa on actualizing Black potential, part 2

Arthur Jafa: [00:00:00] Black people know this as the difference between what you say and what you mean. I mean, and we have a finely calibrated mechanism measuring the difference between what is said to us and what is meant because it's been a matter of survival for us. You know what I mean? And we play. We say one thing, we mean something else. I mean, we made bad good.

Helga: Today we resume and conclude my conversation with the wildly imaginative visual artist and cinematographer Arthur Jafa. I'm Helga Davis and welcome to my conversations with extraordinary people.

When did you leave New York for California. And how come? How come you did that?

Arthur Jafa: I lived in New York for about 16 or 17 years, and I essentially was following my son, who's now 18, but at the time was two.

His mom had gotten into graduate school in San Francisco Art School, [00:01:00] and she moved out to San Francisco with him and we weren't together together so I commuted between New York and San Francisco for about two years and it almost killed me just the back and forth. And you know, I was struggling like financially, so it wasn't easy, but I was very concerned and anxious about losing my emotional connection with my son.

So I just went back and forth a lot for two years and then eventually I was like, okay, this is non-sustainable. I can't afford to do all this flying. I can't afford to be in San Francisco for two weeks at a time where I'm just watching him so his mom could focus on her studies and stuff. So I moved to LA cuz I just thought it would be easier.

And just by happenstance, a friend of mines, two friends of mines, actually I had met that early before, who had actually stayed with me when they were in New York. They said, we're about to get a house in La Mer Park in LA and we're looking for a [00:02:00] co- you know, house person. Would you be interested?

And I was like, sure. Yeah. Space sense. So I, that's how I ended up in LA.

Helga: What was that like to live communally? I hear so many more people talking about that and especially black people as we come up on the 30th anniversary of Octavia Butler and finding communities and ways to share, share land, share resources.

Arthur Jafa: I wouldn't necessarily thought of it in those terms, but yeah, it was an amazingly seemingly magical opportunity at the time. Like, wow, I get to move to LA and I don't got to stress about applying for a lease, uh, getting an apartment. Which, you know, like anybody who lived like I live. On the margins, credit fucked up, all this kind of shit.

It was always anxiety producing, trying to find an apartment, things like that. So it was a dream in that respect. Now, just [00:03:00] naturally speaking as a consequence, I went into what I would say is like more or less the toughest year of my life that I've ever experienced.

Helga: In what way?

Arthur Jafa: A culmination of having turned 50 and being, I could never say I was unloved, but not being partnered in the way that I wanted to be partnered.

So very wounded and romantically, let's say turned 50 and being like, I don't got a pot to piss in. It's one thing turning 30 men broke and chasing your art, or even 40 for those who can hang on if they haven't actually got traction, but shit, 50 is scary. That shit was scary. It was scary. So, there was a point at which I was spending a tremendous amount of time by myself, I mean to the point that Greg and friends, like, you know, Nefertiti and Gugu and Brad Young in particular were on the phone with me.

And they were just like, man, you're spending too much time. You know, I just had a lot of [00:04:00] suicidal ideation, like my kind of ongoing mental health issues, which I had always, uh, managed, struggled with, whatever you wanna call it, came to a head. It was just a miserable, miserable moment in my life where I spent a lot of time convincing myself not to kill myself.

Basically. Whatever the resilience that I was able to muster mostly had to do with my kids cuz I knew. You can just look at statistically parents who kill themselves or harm themselves, make their kids like, it’s some astronomical figure, more likely to haunt themselves. So it wasn't really an option for me, but it was an option that I obsessed about quite a bit.

And it came to a head when I was like, okay, I just need to get my cinematography career back online because I had quote unquote retired from cinematography. I just didn't want to do it anymore. , but it was the most lucrative thing I knew how to do. [00:05:00] And, but I remember a friend of mines had put me forth, she was a, a cinematographer on this TV series.

It was kind of like a Latino Degrassi High kind of thing. Mm-hmm. Low budget, you know, whatever. And she was shooting it and she had to go on maternity leave and she put me forth as a person to replace her. and I went in, I did to talk, I talked to the director, the producers, everybody else. They were like, wow, this is great.

She was there, she was smiling cuz she wanted me to replace her. Um, we were gonna work together for I think four or five weeks with me as a camera operator and her as a DP. And then when she went on the maternity leave, I was gonna take over. I went in, I did the interview, and I was very much in my “yes” “affirmative” mode, whatever you ask me, can we do this?

Yes I can. , yes I can. I was monosyllabic basically like, yes. It was just, yes, affirmative. You know, as people say, they've seen me [00:06:00] talk my way outta more jobs, you know, they knew my work that was like overqualified to shoot kind of what that was, you know? But, I wasn't working at all and so I was like, okay.

Then they said, well, go talk to the production manager. I remember like, man, when they told me how much they were paying, it was so low. I was like, I don't know if I can do this job and survive. I don't know if I can afford to do this job, but I thought at the end of the day, cuz it was like a hundred dollars a day or something like that, and I was just like, damn, I, I couldn't even pay my bills with this.

But I was like, well, at least it's a lot of shooting. So I'll come out of it with my chops being up, you know, up.

Helga: So you found another frame - way to frame.

Arthur Jafa: Yeah. Yeah.

Helga: And to take it as a place where you could also learn

Arthur Jafa: Learned and build on, I mean, I think you learn in every situation.

Mm-hmm. , but technically speaking wasn't gonna be a lot for me to learn in that situation. Cause I really, you know, [00:07:00] post crippling and all these other things. I mean, I've been shooting since my mid twenties, so, you know, I was a veteran. I knew how to do what that was gonna require. I think. But I wasn't arrogant about it.

I thought there was a lot to learn and then I was like, well, yeah, okay. I, I'm gonna try to do this. And then I remember sitting at the bus stop, which gives you some indication where I was in LA and the bus

Helga: Public transportation in and in LA this trip. Yeah. It's not a thing. Yeah. Um, that works.

Arthur Jafa: A lot of people do it, but yeah. You know what I mean? Like nobody chooses to do it. Mm-hmm. . Um, so I was waiting at the bus stop and then I got a call and they said, Hey, we've decided to go with someone less experienced. I'll never forget the way they put it. And I was like, damn, how did I get to the point where I can't even get a hundred dollars a day job?

And I was just, man, I mean, it was just a culmination of everything. I was basically couch surfing at this point. And I remember, I mean at 50, this shit is [00:08:00] scary. It was scary. And um, I remember just calling my dad and said, dad, I don't know how I landed here. Like, I was a person who was supposed to do X, Y, and Z and gave indications that I was gonna get there and I didn't.

And I just was, you know, I felt like and was a kind of failure. And he just said, just come home son. And. We we get you. Regroup. Regroup. Yeah. He just said, come home. Going home at 50 is scary. Mm-hmm. , you know, and I just went and basically sat in my parents' living room for a couple of weeks and just looked out the window.

I didn't know what I was gonna do and my friend Bradford called me. He was shooting a documentary in Philadelphia and had to replace him, so, so you guys should get AJ to shoot. He shot a thousand documentaries. I went up, we were there together for maybe a day and a half, and he split and I shot the remaining four days of the documentary.

So I got a little money in my pocket. I mean, I said a little money. It was a little money, a couple of grand, you know, but it was something. And I just [00:09:00] was like, okay, I need to just prepare myself to go back to LA cuz my kids in LA so I just gotta go back and just deal with it for whatever it is. And, uh, I, uh, was sitting there and I just got a call out of the blue from Paul Garns, who is the primary producer for Ava DuVernay, and also at the time was producing for the Akil’s.

Mara Brock Akil and Salim Akil. Who did like Girlfriends, Being Mary Jane, The Game out there had done a bunch of TV things and Paul was producing a TV series for them. It was a pilot for a new series called The Startup, which was a kind of black Entourage. You know, it would've been a huge hit if it had happened.

I think, uh, they called me and said, Hey, um, Salim and Mara are interested in you maybe shooting this pilot. What are you doing? And I said, well, I'm about to head back to LA. He said, well, don't go yet. Cause they're shooting here in Atlanta, which is where my parents were. And so they [00:10:00] just sort of came out of the blue.

And I even have told Mara and Salim to this day, like I went to him saying, you guys saved my life. I don't think you realized like you literally saved my life. And um, I shot that. It wasn't my vision of where I was supposed to, you know what I mean? But it was a godsend because I could have easily made quarter of a million dollars for two, three months of work out a year and just been free the rest of the year, cuz they don't, you know, they shot on a schedule.

So three months, the whole series and you know, it was a tough shoot. By midway, we had gotten into a groove. Me and Charles, who's my ace on that, and working with Salim who. The most veteran director I'd ever worked with. I could say that. I mean like Salim, the way he saw it, I think like I was just so used to, you do these indie things where it's like a person that's doing one thing every five years or something.

and everything is riding on it. But for Salim, who had directed I think over 200 [00:11:00] episodes, of television, he was just the most veteran person I'd ever worked with. And it took me a second to realize the way he saw things was just very different from any director that I'd ever worked with. Like for him it was just a brick.

And like, you know, you, you lay a brick, it's not perfect. You gonna lay a thousand more, you've laid a thousand before and you're gonna lay a thousand afterwards. Uh, and so we started off a little shaky the first couple of days, but then we got into a groove and I really enjoyed working with Salim. He was very excited about what we did.

And he said, Hey man. I mean, I'm, I would just ask you right now, this is almost like a guarantee it's gonna get greenlit. Like would you shoot the series as opposed to just the pilot? And of course that was a blessing at the time. And so I had come to Atlanta being distraught. And got out of there with a brand new car.

A Prius at the time was a big deal for me. They literally shipped the car back to LA for me. The production did with this job sitting in front of [00:12:00] me. They said it's gonna happen in the next two or three months. And so I went back to LA uh, you know, with a sense of like, uh, possibility. I had also very recently, Right around that same time, a really close friend of mines Craig Street introduced me to his therapist, who became my therapist, and very quickly said, I think you could use some pharmaceutical support.

Which we did. And it kind of changed my life. I mean, like all of it together kind of changed my life. Um, uh, so all of a sudden I remember like, I just gotta hang on till we go back to this other thing, you know? And, uh, and it got pushed once. And then I was like, oh shit. I remember sitting on the side of the bed thinking like, well, wherever I go, I'm not going back to where I was, so I'm gonna make something happen.

And a good angel friend of mines who I've mentioned once already, Khalil Joseph. Someone had asked him about shooting [00:13:00] a documentary for, uh, German television, Zeta ZDF. Uh, it was coming up on the 15th anniversary of The March on Washington, so this is like 2003. And, uh, they had two nights of programs set and they had space for a specific thing, which is supposed to be a look back at The March on Washington.

and Khalil initially was supposed to do it, but I, he couldn't get his head wrapped around kind of what it was sort of, I think it was generational, just a age thing. And so he, before he gave it back to him, he said, Hey Jay, are you interested in doing this? And I was like, yes. Before I even read it. Yes. And I remember just writing, like literally sitting on the side of my bed and just writing a crazy treatment.

It had very little to do with what the project was supposed to be. But I remember just basically saying, well, I don't wanna do a documentary about the March on Washington. I was like, haven't I seen it before on PBS multiple times? I think I've seen mm-hmm. multiple versions of that. I said, what I'm more [00:14:00] interested in is doing something about where black people are now.

I remember just framing it as like, I'm interested in the afterlife of the March on Washington, and I just, I just want to talk to people because this is supposed to be a golden era for black folks. We got all these black billionaires and all this. Stuff, CEOs and all this kind of job, but black people don't seem happy.

We don't seem collectively like this was a golden age. And, uh, and they, I just think in hindsight it was just too late for them to give it to anybody else more than anything. Uh, so in that sense, my sort of fleshly angels and my guardian angels intervened, and so was just fell into my lap. Little on the oversight and we just shot it very, very quickly.

Like in the course of a week or so, flew like to New York, did as many people in New York as I could do. Then went down south starting Atlanta. Kathleen Cleaver, people like that - did my dad, my cousin, a bunch of people. [00:15:00] uh, you know, where I can get my hands on. And then just did a road trip. I think we went to Nashville to do Hortense Spillers.

I hung with Fred Moton in uh, Arkansas, which is where he was from. We were just moving around just one day here, one day, one day in a van shooting as much and as quickly as we could and had always planned to do like Chicago and some other cities and stuff. We just ran out of time and money. And, um, you know, and just put it together very quickly.

And, uh, it turned out to be this thing I did called Dreams are Colder than Death. It, uh, showed at the Black Star Film Festival where it got an award it didn't show at the New York Film Festival. I got a commercial gig as a result of it, more or less. Which went south, meaning they asked for something and then when they saw what they asked for, they were like, whoa, this is not really, and so they did what's called re-brief, meaning like on a commercial, if a person said, we want you to this, [00:16:00] and you do it on the inside, and they don't want that.

And so they basically pay you off because you fulfill your contractual - right, yeah. And they oftentimes will just hand it over to a editor or with footage. They try to make whatever the new thing they gonna make of it. I was in New York and they said, uh, you know, Hey, you, here's your check.

You can bounce if you want. But I was already in New York, and so I was like, no, I'm gonna hang around. I'm curious to see the process. And somebody asked me something like, you've been a person who has theorized a lot about black cinema. Why do you think, you know, you haven't been able to fully manifest some of these things?

And I said, well the first is mental health issues. And people were like, people even laughed cuz they thought I was making a joke. Oh, I don't know. It was just something about the head space I was in at the time. I just didn't want to lie about those things. And I just was like, just very straightforward and honest.

[00:17:00] And I said, yeah, you know, there's all the structural reasons. that I've talked about before, but I just think my own, you know, issues and stuff and so that job went south, but I was sitting there every day. I got bored with what they were doing, and I just went and I sat and I put Love is the Message together in about two hours, like I said.

You know, the art world was the furthest thing for my mind. At that moment. I was thinking, oh, this is kind of intense, what I just put together. I remember crying when I put it together. The first time I looked at it from beginning to end, it made me cry because I think in a way, I just strung things together.

That moved me for whatever reason, sometimes they move me because, cuz you know, that was that moment where all of a sudden, whatever the cell phone camera thing cook kicked in between YouTube. It was a moment, well, all of a sudden - like Rodney King was a harbinger 20 years before because they just ha, some people just happened to have a video camera when the shit went down, but we know the [00:18:00] shit is going down all the time, and once it hits some kind of critical mass of people having cameras in their cell phones and then somebody just saying, oh, you can videotape the shit?

Then all of a sudden there was this moment post Tamir Rice and stuff like that. All of sudden you just start seeing footage. It just was like a wave of footage all of a sudden, and I was like everybody processing it.

And so between that, I just had been collecting things as I would see them with no real intention around what to do with it. Just would just save it compulsively. And I had a file full of stuff and I just strung it together and I was like, wow, this is intense. I remember showing it to the editor. Who had been working with me on the job, Chris Mitchell.

And he was like, whoa, Jay, this thing is intense, man. And uh, like I said, I saw a week later, Kanye do Ultralight Beam. I put it together, which is magic from the beginning. And then Khalil and other friends, Greg was like, don't put it on YouTube. I was like, I want people to see it. Don't put it on.

YouTube. I want people to see it. . [00:19:00] And then Khail, like I said, sort of took it put forward into his own hands. He just put it forward in the. That would've never occurred to me. Gavin Brown, my dealer, great, incredible dealer, saw it, tracked me down in LA and then he was like, I saw this thing you did. I was like, what thing you didn't see?

No thing I did . You know what I mean? He started describing, I'm thinking like, shit, that sounds like Love is the Message, you know? But I was like, how would you see it in Switzerland? You know what I mean? And then he mentioned Colle, and I was like, oh.

Helga: You are listening to Helga. We'll rejoin the conversation in just a moment.Thanks for being here. The Brown Arts

And now let's rejoin my conversation with video artist and cinematographer Arthur Jafa.

Arthur Jafa: And so we come full circle. Full circle and you know, and Gavin had opened his space in Harlem of all places. He hadn't had a space for a couple of years. He had been like just doing art fairs. And so he had put all of his resources into this space on the 127th Street, which was a fairly radical gesture.

You know, Harlem was not where people were thinking you were gonna have art gallery. And it's an amazing space. It's the most amazing space in New York, even now. And, uh, it wasn't open. It was still a construction site. I said, look, I'm gonna be in New York in a few weeks. Gonna shoot a documentary, and he said, well, I'll meet with you afterwards.

We were shooting in Harlem. I just walked over to his space. When I finished, [00:21:00] we ended up hanging out for four or five hours. The next morning he called me 10 o'clock , you know, and he said, well, first of all, we should show this video. Mm. And I was like, well, okay, as part of a group show or something. He was like, no, just the video by itself.

This was like late November. And I was like, next year he was like, no, in two weeks. You know, I was like, fuck. Two weeks. I was like, is that possible? He's like, let me worry about it long as you're down, we'll take care of everything. And I was like, okay, cool. And um, it was about three weeks later that we opened it in Harlem, in his space.

He said he wanted it to open before the election. and Trump got elected and people showed up for love is a message. And you know, and that's how it went. You know, it was a very intense party around it. And someone said to me in England, like a few months later, legendary party. DJ Reborn was spinning the music.

People were [00:22:00] dancing hard. I think they let of some steam from the whole Trump thing. I remember people looking at Dave Chappelle on Saturday Night Live before the opening. We just used the screen to project it cuz everybody was like, Dave Chappelle is gonna be, you know, he's coming back outta retirement and he's gonna be on it and he's gonna be talking about obviously, the Trump thing and all of this.

And I don't know, it was just a work that kinda. I don't know. It just rode that moment, whatever that was, you know. But as I said to people, like, yeah, but I made this, I didn't make any response to Trump. I mean, I was like, right,

Helga: You were just just doing your work. You're doing your work.

Arthur Jafa:And I was like, you know, again, just being resistant to these sort of narrow readings of things. I was like, I made this under eight years of Obama's reign, not under Trump. You know what I mean? Like all this shit we are talking about killing black people. This shit is happening not under Trump. It was happening under Obama.

So, you know, it's not so straightforward as people like to think. These things are.

Helga: And we keep [00:23:00] talking about that as well.

Arthur Jafa: Yeah, yeah, yeah. That it isn't, yeah, this or that. Yeah. I, I like to say like when people have even asked me about what Aguire is about, and I will say, well, because Saddi always say AJ is definitely not good talking about the meaning of his work, which is true.

I have no idea. I make the work the meaning, I speculate about it, but I'm not like the best person. But when I am the best person, About it is talking about the process, like how I arrived at making or I'm really good about process, I think. And so with the AGHDRA, remember saying, I'm not sure what it's about.

I have a more of a handle about what it's about now. Cuz amongst other things, I think it's a, it's a premonition of Greg passing, for example, some conclusion I came to when I looked. With Greg's daughter Chinara, and she shared some of the things that he was saying about it, and we looked at it in light of Greg passing, and it's just impossible for me to not see it.

Yeah. He just feels like he's all over it, you know what I mean? But, um, [00:24:00] but AGHDRA would say, when people were asking me about it, well, what is it you know about? And I was say, well, I don't know what it's about, but I know I was very preoccupied with this term, discrepancy around it. Like, so as we evolved it, you know, it's a wave sort of molten wave piece, what

I guess you would say, I was very interested from the beginning that it had some relationship to a specific thing, but as soon as we locked that in, I was shifted. So it's like it's a wave. It's not a wave, it's a body. It's not a body. It's Africans who would, you know - The transatlantic slave trade.

It's Miles Davis' skin stretched on the Atlantic Ocean. It's an anthropocene vision of the world after man, a thousand years after man has, you know, gone extinct. You know, I remember asking my good friend Kerry James Marshall. The difference between painting and a photograph and he said immediately discrepancy.

Mm-hmm. So meaning like there's a disjunction between the rendering of the thing and a thing. It's a little like in the space on some level of, [00:25:00] or disruption, very deridias of the relationship between a sign and a signified, which is, you know, the first time I've read that I was like, well, black people know this.

Says the difference between what you're saying and what you mean. I mean, and we have a finely calibrated mechanism measuring the difference between. Said to us and what it's meant because it's been a matter of survival for us. You know what I mean? And we play, we say one thing, we mean something else. I mean, we made bad good.

This shit is bad. meaning like, this shit is good. You know what I mean? So it's one of our superpowers, you know, so discrepancy. You know, like I used to say, when James Brown, he didn't just say his shit was bad. He said, my shit is super bad! Right? And super bad means like, not just bad, not just casually or almost like arbitrarily bad, but like, You know, uh, like unrepentantly bad, which would seem like, why would you pursue that?

So I was like, uh, thing about discrepancy. But see, the thing [00:26:00] is, and I just figured this out recently when people asked me about the kind of work that I'm interested in making and the kind of work that I like, I would just say, well, number one, I just not interested in making remedial work. You know, and remedial is like, A is for apple, B is for ball, C is for cat.

I'm just not interested in, and I realized just recently that those two things are tethered together. My embrace of the discrepancy between things and the remedial of things. I mean like, In the true complexity of it. Everything that's great has to have a little of both. In reality, it's gotta have a little shit that's on the nose and a little shit that's way left and right of the nose below and above the nose.

You know what I mean? But it's gotta have, when they say being on the one, like if we thinking black music being on the one, this question you said about. You know, Muddy Wilders and being in key, well, you gotta have a little of both. You gotta be a little ahead and behind the beat. You got a little be to be in, [00:27:00] in key and out key.

That's what gives attention. Having both things in equal measure or in dynamic measure with each other. So, . I can just see it back in my life. If it's like one term, it's becoming a term that's sick. The move back and forth between Clarkson and Tupelo was by discrepancy. That was a discrepancy between the two environments.

We think of environments as being stable, right, and a real thing. And you are the one that's in flux in relationship to the backdrop. But it was like no foreground background. What is foreground and what is background you know?

Helga: Last question I wanna ask you is, is there a thing that you do every day or most days that every person can do to hold some part of you that needs nurturing or a part of some practice that you have a thing that you do that's part of your artistic practice, that [00:28:00] every single person listening to this can do?

Arthur Jafa: Well, the real thing, if I'm being perfectly honest, yes. That I do every day, is Instagram. I hate to say it. I hate to say it.

It's true. Aw. I'm a little obsessed with Instagram. I don't post very often. But I also look on Instagram. Very addictively. I would say compulsively. But the reason that I'm predisposed to Instagram is because I've always been about images. I've always been about looking, looking at images.

Helga: So you do things to support your interests in images.

Arthur Jafa: It's like compulsively, I think about them in a certain way. Over the years, I've learned to think about it, but the compulsion to see images preceded me thinking about 'em in a certain way.

Helga: Okay, but that's part of your work. Yeah. So if I want you to express to me a thing that can help me be on whatever my journey is, what's a thing?[00:29:00]

Arthur Jafa: Hmm. Well, probably would say something like, when I'm trying to, uh, counsel my son who's an artist, I'll just say, follow your bliss. And, and, but part of the following your bliss is like, what kinds of things intercede or disrupt that. It's not just, oh, put this in your mind and pursue that. Pursue the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Okay. Easy enough to say that. But the thing is like, what's all the shit in between you and the pot of gold? So how do you, how do you do that? Well, for me, I would say there's some people who are perhaps, I would say, more gifted than me. Uh, were situated better than me. I grew up thinking like, God, why am I in Mississippi?

[00:30:00] And a lot of my energy going into my teenage years, my adolescent years was about how do I get the fuck outta here? It's a kind of inverse pursuit of your bliss in a way. It's a kind of getting away from the things that you feel are blocking your access to your bliss. Bliss being just. Not necessarily nirvana in the sense of the thing that gives you total or perfect pleasure.

That's not what I mean by bliss. I mean, getting good and comfortable with. The things that trouble you, the things that attract your attention, just on that level of consciousness, what it is that your eye goes into when you walk into a room. You know, I always say to folks like, look, you got to get out here and try enough things to get an idea of what it is you should be doing.

Like you gotta have a big enough sample to even figure out what your compulsions. If you put an apple on the table and you say, that's what I'm attracted to, well, what is that? You gotta put an [00:31:00] apple next to a firetruck, next to a wagon, all of which are red to realize it's not fruit. It is red is what you're attracted to.

You need to have enough in your basic sample to figure out the venn diagram, what connects all these things. It's red. So a lot of, for me, like having trained myself to not do what I think it's kind of human nature, which is a recoil from the things that disturb you. I mean, I have definitely trained myself to not recoil or at least to not stay in that moment of recoil from the things that, uh, disturbed me, but to push towards them.

And that's a learned skill, but I think it's at the core of everything that I do.

Helga: AJ, thank you.

Arthur Jafa: Thank you for having me.

Helga: having me. Thanks for listening. That was the second half of my conversation with Visual Artist Arthur J. [00:32:00] I am Helga Davis, and it's been a pleasure to share these conversations with you. This season, there's been all manner of advice for living a fuller, more open life from our guests.

But from the wisdom of Claudia Rankine, I leave you with the one word we can all write on a piece of paper every day. Listen.