Video artist Arthur Jafa on actualizing Black potential, part 1

Arthur Jafa: [00:00:00] I've come to the conclusion that life as we understand it, is a narrowly dimensionalized sliver of existence. Like if you sit down and you play chess or checkers, the board is flat and it's a 2D thing. But fundamentally what it is is a symbolic enactment of human conflict, but it's a narrowly dimensionalized enactment of human conflict and opposing interests.

But I think life is to existence as checkers is to life.

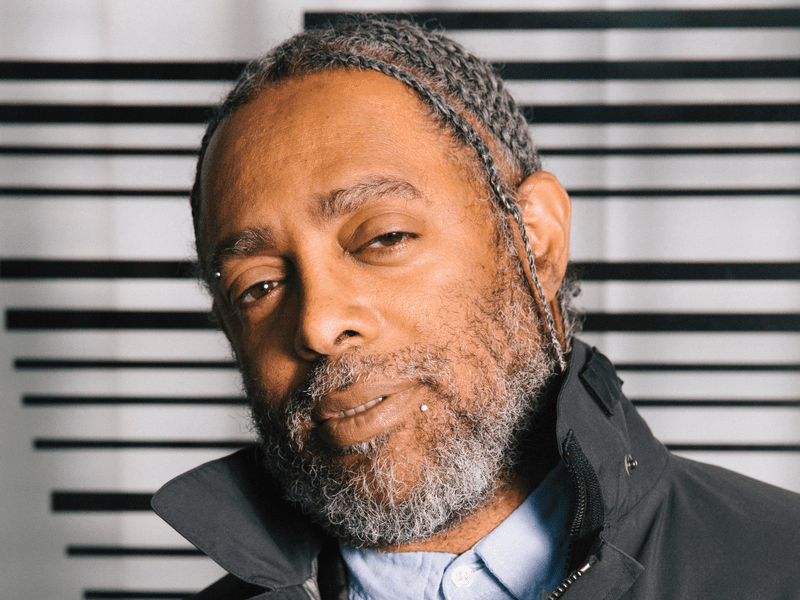

Helga: My guest today is the American Visual Artist and cinematographer Arthur. Arthur's work. Over 30 years in film, has captured the histories and experiences of Black Americans, projects that exemplify both the universal and particular facets of Black life.

I'm Helga Davis and welcome to my conversations with Extraordinary people. Our conversation today is [00:01:00] a masterclass in Black thought, a free fall. Through his breadth of knowledge and understanding of Black visual culture embedded with the references, rhetorics and personal reflections of someone who has spent a lifetime dedicated to centralizing the varied experiences of Black.

Being speaking with him was like listening to the musings of Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, and Orette Coleman - playing a tune together, except this tune is coming from just one person, and like any great musician, you don't interfere and ask them to go back to the top. You listen and let them flow. As something new.

We're going to split this conversation into two parts, part one today and part two next week. Be prepared, follow along and get out to the other side.

I was reading, [00:02:00] and I've been reading this book, Culture Strike by Laura Raicovich. And she quotes Christina Sharpe, Hortense Spillers, and Saidiya Hartman. And they say there is no such thing as a neutral gaze, particularly when it comes to Black subjectivity.

And then it goes on to say, When an artist enters a space of pain and suffering, it comes with responsibility. It must be done with such intention and knowledge as well as a sensitivity to how audiences may read the work. And I wanna know where you feel you fall into that conversation with your work.

Because for me, you are holding a place. Of witness of, of very deep witnessing. And I don't know that the point [00:03:00] of the work or any person of color's work is to represent or to, uh, hold a mirror to anything, but simply that they do their. Is that a possibility you think?

Arthur Jafa: Witnessing?

Helga: No, I know that you do that.

Arthur Jafa: What Uh, my sort of initial response is not a yes or no response. It's a kind of, I have adopted over time or developed. Some internal mechanisms around what it is that I'm doing. Oftentimes, they are mechanisms when I attempt to articulate them that resist narrow or reductive readings of what it is that I do, which is not to say I'm not doing those things just to take Love is the Message.

For example, it was often very early on, constructed as being largely a sociopolitical gesture. Mm. But it's not the only thing that it is, and I'm not even sure that it's the [00:04:00] primary thing, that it is, certainly not for me as an artist, as a person who made it, it was made very intuitively. It wasn't made with any kind of, uh, specific intent around what I was gonna do with it.

I made it very, very quickly. I put 90% up together in two hours. and, uh, heard Kanye's Ultra Light being performed on Saturday Night Live about a week later. So put the music on after it was cut together. Spent another couple of months filling with it, but essentially 90% of it was in place, like just immediately.

So I say you edited it that fastest say, I wouldn't even call it edited, I just strung it. I think a lot of what people sense when they're in the presence of it, it looks very much like a music video, which on one hand it is, but at the same time, very few people refer to it as a music video because in this way, , it contradicts one of the basic assumptions about the music video, which is that [00:05:00] the images are following the sound.

Mm-hmm. , and that's not the case. There's a complex kind of rhetorical relationship between the sound and what you're seeing. Half the things in there, I have people saying I adamantly don't even agree with. I mean, actually I disagree with some of the things that I have people saying in there. So when people would lean into early on the sociopolitical reading of it, and then I would push back and say, Those two things were both held equally in my hands when I made the choices that I made.

So, so for me, I don't want to be the prisoner in a box, even if it's a box I made. I just wanna keep my maneuverability. Um, so the kinda witnessing part that I think. For me, it is a given aspect of what I do. You know, if there's anything remotely like a responsibility, that's it. I just want to bear witness to what I'm here to see, what I've seen.

Uh, but I'm not, I'm not interested in protest. Me personally, protests [00:06:00] are, I'm not, um, , I'm interested in protests. Mm-hmm. , but not protests, art so much. Mm-hmm. . But, uh, I know oftentimes there has been a tendency or the implication that there's something primarily activists about it, and activism is critical and important in society.

You know, society doesn't succeed any change without. without agitation. We know that's this to be true. This is a fact. So I'm not trying to diminish the importance of that at all, but I'm very, particularly at this age, very clear about what it is I do and what my skills are. And I would say that I'm like an alchemist.

Mm-hmm. the kind of change that I'm interested in. Catalyzing or provoking. It's not so. Subtler kind of change, but it's maybe a more structural change or it's acting on fundamental kind of stuff. You know, it's not really like what the politics of the day are about. It's really trying to figure out how do you make [00:07:00] emancipatory acts?

How do you make a transformative change? We, we all love mathematics. I love Malcolm X, I love Martin Luther King. I don't see them opposed in any way. Uh, and their sacrifices are incredible. But then there's a John Henry Clark who lived to be like damn near 90 years old, just dropping bombs. But just because of how he moved, it just didn't draw the kind of attention, you know what I mean?

That a Malcolm or MLK would draw. What's the difference between, you know, a Charlie Parker and say Duke Ellington? Mm-hmm. I'm like, in many ways, The Duke Ellington model is not as romantic because it's not as tragic. There's something about a Jean-Michel Basquiat, a Charlie Parker, or Jimi Hendrix. It's fascinating, particularly as a Black person because the sort of pronounced sense of latency. [00:08:00] A person demonstrates incredible capacity, but then we don't get to see that capacity played out. Mm-hmm. So it's inherently fascinating for Black folks. I used to use this term all the time. I call it Black potion. Black potion as a fundamental aspect of Black being meaning like, This sort of inherent tension between actualizing and not actualizing your capacity.

That's central to Black being. And in these instances, it brings that thing to a crux of what the person was capable of. Anybody who grew up around Black people or in Black communities know that for every Aretha Franklin, there's 20 motherfuckers who people will say, oh, if you had been in that church, she would've killed, are.

You know what I mean? She just didn't, in a white supremacist environment that's full of minefield, she just, or that person wasn't born in the right place at the right time. They weren't lucky. They didn't have the things fall into place the way they did, so you never heard of them. But it's something that everybody's familiar with because it speaks to potentiality.

[00:09:00] Mm-hmm. and whether that potentiality is fully actualized or not, because on the kind, most almost elemental. The story of Black people in the Americas is a story of frustrated. And in these incredible instances, fully actualized capacity. I mean, the whole thing that's always that question is our capacity.

Mm-hmm. , our humanity, our genius, all these kinds of things. This all comes down to what are you capable of and to what degree, and what are the forces that are aligned against you actualizing that capacity. So in those instances where there's a premature but demonstrable genius, People are fascinated by, it's not as fascinating as.

As amazing as Prince is, it just doesn't have the same charge. And so, or Cecil Taylor, who's like my God, right, but who was ahead of the curve and stayed ahead of the curve. Nobody ever caught up with him. And so [00:10:00] those are different kinds of models. What would Jimi Hendrix have done if he had just lived three or four more years?

Like you saw? Hendrix ended up in London because he couldn't get any traction here. His thing took off there, but they had framed it, power Trio, white Rock kind of thing. They framed it like that and he spent. I mean, it's weird to say the rest of his life cuz that was only three years, right? 67 and 1970 , that's three years.

It's amazing when you think about how transformative and, uh, just did redefined everything that three years were, but it was only three years. So, . If he had had a normal, let's say even a moderately normal maturity period, we would've seen him, I think, move in some ways that he was trying to move, but it just took a second because he had, you know, found himself in this box.

Mm-hmm. . It was a successful box, but it was a box. And so, but that's why Jimi is fascinating versus like a slot [00:11:00] stone. Mm-hmm. , who, if he had just died, Right after Riot or right after whatever the record was, right after Riot, we would think about, in the same way that we think about Jimi, like what would he have done?

What could he have done, but because he didn't die? Toughest nails, whatever you want to say about sly existence, toughest nails like miles, just a survivor. I mean, some people look into the abyss and they shout back what they see, and that's it. It's swallow of them. Mm-hmm. , there's some people who can look into the abyss and they're just fucking toughest nails, like Miles looked into the abyss and just stepped back from it.

So if you see a slide or something like that living in his RV or something like that, it's like he's not supposed to be around. He supposed to be like Hendricks or something, you know what I mean? Mm-hmm. just like a figment of our imaginations to a certain green. He's not. So my kind of. Interest in an obsession with these questions of actualization, like I termed it, Black Potention [00:12:00] is just bound up with the whole primary questions of what it means to be a person of African descent i.e. Black in the context of the Americas.

It's like, you know, the Black story in America is the American story. It sounds corny to say it, but it's true. It's the American story and it's the story of like, what is. A person capable of. Hmm. And what are the forces and what is the investment in those forces in frustrating or, um, resisting that capacity?

So,

Helga: Where are your people from?

Arthur Jafa: Mississippi? Mississippi? Like everybody's people. Not everybody's people, you know, it's like where are the people from? The people are from Mississippi or Alabama, but the south, you know, I grew up in the Delta, the Mississippi Delta. [00:13:00] I grew up kind of in two places. I was born in Tupelo, Mississippi, which is decidedly not in the Delta.

Northeast Mississippi and uh, uh, that's where I was born, that's where my mom was born. All my cousins, aunts and uncles. And, uh, in 67. My parents relocated me and my three brothers to Clarksdale, Mississippi, which is at the very heart of the Delta. Sometimes people used to call it the capital of the delta.

And it was, uh, a very different environment from Tupelo, you know, in that, in that like Tupelo was the model post segregated southern town. It was a town which. Integration embrace it. I think mostly because the leaders of the community saw integration as an inevitability and not really worth resisting at the end of the day, because I don't think ultimately in Tupelo they seeded and in control.[00:14:00]

Of the municipality. And that brings us back to exactly what you were talking about. Yeah. They didn't see it any control of the municipality, but they understood that there was gonna be more benefit to working with the inevitability than resisting the inevitability. So if you look at Tupelo now, then it's just totally bereft of industry and you know, in Clarksdale it's just a Black town.

You know, it's very much like Jackson's been in the news recently. Mm-hmm. and the water, the infrastructure's collapsed and all this kind of stuff. It's cause Black Jackson is a Black town, not in the Delta, but it's a Black town and it's been at arts with the state government, which is white controlled and run since it sort of became a Black town.

But I grew up between Tulo and Clarksdale and moved back and forth between one and the other on an almost weekly basis. Mm. And so that definitely shaped not just my consciousness, but my personality in a lot of ways, because it's like moving back and forth between. [00:15:00] Like, if you can imagine a person who spent one week in an apartheid era, a South African the next week in Angola, which was like a post Marxist socialist society, you know what I mean?

If you were going back and forth and having to code switch or understand, it left me feeling pronouncedly alienated in both environments. And so it's something that I think has characterized my interests, who it is I gravitate towards, the kind of work that I'm interested in making. I remember talking to, you know, obviously my friend Greg Tate before he passed.

I had just finished, um, a gig. It was something that I had worked on for almost two years through most of covid. I had worked on it and presented it and, uh, it was super well received, which somewhat surprised me. I went into it feeling like, okay, I'm about to approach my first like, Great Public failure, or something like that?

I mean, I really felt like that, and it wasn't like, because I didn't [00:16:00] think the work was good, it's just because it just seemed like it was obtuse and it just didn't do a lot of very intentionally, it didn't do a lot of the things like say love is message does. It just didn't do those things in some ways.

The kind of contrarian part of my personality made it to not do those things. And so whereas Love is the Message was composed of found footage of AGHDRA has no footage in, it's all cgi, it's all generated. Whereas love is, the message is full of Black figures. It's figurative work. Has no figures in it. You know, it has a thing in it that you can't tell if it's a landscape, meaning a backdrop or an entity.

Like, you know, is it foreground or background ? You know what I mean? I mean, it leaves that to the viewer to the side, so, So it was very intentional and it felt like I had realized something that I had been striving towards since I was, uh, in my early twenties, which I think is when I, my [00:17:00] consciousness as a artist consolidated itself and that consolidation totally bound up with meeting Greg and becoming, you know, he is, as I've said, the love of my life, you know?

Yeah. Like just becoming best friends and, uh, . I think a week after AGHDRA opened, I was on the phone with him and I was just saying, yo, dude, why do I feel so unsettled? I just thought my whole life, the sense of unsettledness that I felt had to do with not having succeeded, not having actualized, you know, my fantasies of what success was gonna look like, and, uh, , I mean the people who defined success for me growing up was like, for most people my age, I was born in 1960.

Michael Jackson, the Jackson five, and Michael Jackson was a level of success that, I mean, you wanna say on one hand it was unprecedented, but that sounds as if, almost as if we like products. Thirties or forties or something. There are just no other [00:18:00] examples of it. You're looking at the landscape. There's no other young Black person, and here it is, the Jackson five go from having songs to having a Saturday morning cartoon when there was no other Black folks on Saturday morning cartoons, period.

And so that was always a kind of, metric, a public metric, a shared metric of what it means to succeed. I mean, I was practically a grandfather before I achieved any real success. I mean, I had some successes. Mm-hmm. , but they were oftentimes, or generally speaking, in support of other people's art. I mean, my most arrogant sort of way to frame it would be something like, it's like John Coltrane in Miles Davis Band or something like mm-hmm.

you know, you did your thing, but it's very much Miles's thing. And so I was 50 before I, I did anything that kind of felt like it was my own and you know, and it felt real and [00:19:00] substantial and something that I felt like wasn't gonna go away. Like even when love is a message, which was never intended for the hard world, I just wanted to put it on YouTube.

And all my friends were saying, don't put it on YouTube. Don't put it on YouTube. And a very close friend, Khalil Joseph, basically took it with him too. Basel unbeknownst to me and showed it, and Gavin Brown, my dealer, saw it there, tracked me down. And hence, this is where I am. So by the time I actually do a Gira and I'm sitting there like, wow, I didn't anticipate that it was gonna be as well received as it was.

Uh, and I'm talking to Greg about it on the phone. It's like, why do I feel so unsettled when Greg said just, he said, motherfucker, you are a Unsell n***a. It ain't got nothing to do with. You know, you have never had a movie or a hit, you know, anything. It just, you just unsettle. And it's funny that it would take somebody to say it back to me.

I mean, that is completely aligned with what I said about moving back and forth [00:20:00] between Clarksdale and Tupelo. Mm-hmm. It's unsettling. It's unsettling to be in an environment that's segregated. and to say this shit is not normal, or to be in an environment that's integrated and say, this shit is not normal.

I'm just unsettled in that way. And it has, even though for most of my life I've taken it to be a product of not having succeeded. Hmm. And I can see now that it has nothing to do with not having succeeded. It just has everything to do with my personality, you know? So

Helga: You’re listening to Helga. We'll rejoin the conversation in just a moment.Thanks for being here.

The Brown Arts Institute at Brown University is a new university-wide research enterprise and catalyst for the arts at Brown that creates new work and supports, amplifies and adds [00:21:00] new dimensions to the creative practices of Brown's arts departments, faculty, students, and surrounding communities. Visit arts.brown.edu to learn more about our upcoming programming and to sign up for our mailing list.

Helga: And now let's rejoin my conversation with video artist and cinematographer Arthur Jafa.

Can you remind me the story of when, when we first met,

Arthur Jafa: Um, well, we didn't exactly meet, right? Yeah, exactly. I don't, I don't really have a memory of having first meeting you. I have, uh, a memory of you being there. Okay. You know, there was a meeting when you got, I saw the band Women in Love, all Apart. And we were all very super young.

I mean, I would just say that too, not in the defense of it, it was what it was, [00:22:00] but when, uh, Women in Love kind of came apart was one of the most mortifying things I've ever experienced. Mm-hmm. I mean, I, I'm not saying there weren't things leaning up to it, but I saw the moment where you would say, okay, if you were gonna dramatize a moment, that was the moment in the office between the managers and this, it's like one of the few times.

in my life where I can say my good friend Greg, the classic Libra, who has all that equilibrium that he had and could manage a lot of kinds of personalities and stuff seemed thrown off of his center. Like at the end of the day, in response to the things that you guys were saying, it kind of came down to what, well, this is just the way we we gonna do it because this is my band.

And I remember pretending to be asleep through most of it. Cause it was so fucking mor mortified to be there. I was just like, I'm just gonna lay here like I'm fucking asleep because this shit is crazy. You know? And that was the end. And then I think he more [00:23:00] found his footing. with burn sugar, you know what I mean?

And just started to, I think he, he got a better grasp of what it meant to be a real collaborator. Nobody's perfect, you know? And I wasn't a member of the band, so I don't know what it looked like inside. But I would say from the outside it looked like he very much had learned his lesson. What was

Helga: Interesting about, I mean, I completely remember that meeting.

Mm-hmm. I came with my piece of paper.

Arthur Jafa: Oh no. It was a mutiny, and it was a mutiny. It was a slave insurrection. It was an insurrection. I don't know about slaves, but it was an insurrection.

Helga: I came with my paper. I had my points right because it was the first time I had actually experienced a love that I wanted to fight for.

Arthur Jafa: Oh, interesting.

Helga: Mm-hmm. And that I didn't want us to break up. Right. And I thought that if I came with my list mm-hmm.That there would be some kind, like I [00:24:00] could get it off my chest. Right. One thing. Right. And that there would be some kind of, wow, baby. I didn't know you were feeling like that. Right. Right. And you know what, let me, let me sit down with you And work this out and,

Helga: and see what you're saying to me and, and let me talk to you about where I am. Mm-hmm. . and let's see what we can do.

Arthur Jafa: Right? , but that wasn't his response. His response, it just, it sorta, it was like his normal cerebral, and I think some emotionally sensitive response just got shut down and it provoked this kind of hard line thing.

Because I remember it was saying something about being in tune, being out of tune and who it was was gonna be, the person was gonna be able to decide. And I was just like, yo, this shit is crazy. It was cray cray. Lemme say, you know? But I think it's interesting because like in some ways you have to reduce it to some, you were saying it was kind of like [00:25:00] this, this is my band and y'all are in it.

And that's why I always think of Burnt Sugar came outta the ashes of women in love because it was a kind of thing that he was very resistant to saying. He resisted from the beginning, from saying, this is Greg Tate's Burnt Sugar. It just became burn sugar, which had a very pronounced collective you know, like we are adults, we know these things in real time don't necessarily perfectly align with your ethos, but that certainly was the ethos of burn sugar very differently from Women in Love.

Even his adopting a Butch Morris conduction strategy as a primary component of what Burnt Sugar was, is a little like a way of kinda asserting a kind of direction and control overing, but seeding also to the ensemble, uh, some of the sense of who it was that was dictating what it was gonna be. That's how I always understood it.

Helga: I think the thing where, where, I mean, definitely [00:26:00] guitar tuning was, was on my list.

Arthur Jafa: I mean, I'm just saying that's one of the things I remember.

Helga: No, and, and I'm just gonna say, it was so hard to sing those tunes right in tune. Mm-hmm. with his guitar, a half step somewhere else. Right. Up, down, wherever.

Yeah. But his argument to me around that was that I had been around too many white people. Right. And that, uh, Muddy Waters guitar wasn't in tune and

And I said, but you're not Muddy Waters. Right. And we're in a different time. Right.

Arthur Jafa: And he would see that now that he's not muddy. He wasn't muddy waters, but, uh, but yeah.

Helga: Yeah and I remember he came at me with a whole box set of Howlin Wolf and he's like, you need to listen to that. But it was his stance that, that I [00:27:00] was somehow not Black enough. Hmm. And I don't think he believed that. I think that his response in feeling attacked and feeling outed in some way. Mm-hmm. took him there. Yeah. And you know, the, the truth of it is that I never, ever. Stopped loving Greg.

Arthur Jafa: And I don't think he thought you stopped love loving him.

I don't think so. Yeah, I don't think so. That's as a person who knew him. You know, for 40 years intimately. That was never the sense that I had of, I mean, we all have those moments where we show our asses. That's so that's just, it was a show you ass moment. It was about the only one I personally experienced with him.

I mean, for a person who was my friend for 40 some years, we never had an argument. I mean, we argued about intellectual things, right? But we never had a [00:28:00] ar, you know, we just never did. Me and him just got along, you know? So, But I would say it's one of the only him showing his ass moment that I ever witnessed.

I mean, I could say that cuz I love him and I think he was like a legendary , you know, he was a mythic, legendary person. So it's hard for people who weren't there to imagine the kind of critical authority that Greg willed at the time as a critic of Black music. So for him to actually get in the game, I don't think people recognized how tough that was.

Mm-hmm. Cause people had their knives out, they were ready to skew him. Cause he had just been sitting back for, I don't know, X amount of years and. Very surgically taking people's shit apart. I mean, praising the things that he thought were their praise. And I don't find Greg to be the kind of critic who went after people too deep.

Mm-hmm. . But oftentimes [00:29:00] him ignoring you felt like. he got in your shit. I mean, the fact that he wasn't actually celebrating you felt like a critique on a certain level. I mean, me and him are different in that respect that I always thought Greg was a very generous person with regards to his critical assessment of Black people's musical production, but a lot of people didn't like the power that he wielded.

Mm-hmm. . And they were like, well, motherfucker, it is easy to sit back and talk. , it's a lot harder to do. So I just think the kinda willpower that it showed and his capacity to push on through two burn sugar, which made itself a part of the tradition. Mm-hmm. like women in love is part of the story of Black music, but I wouldn't say women in love is part of the tradition.

Burnt Sugar is part of the tradition. You know what I mean? It's a marker. It, it meant something. It stands for something. If you wanted to tell the story of Black American music in the last 25 years of the 20th century, you would touch on burn sugar because they stood for something. They would've sort of repository of a number of [00:30:00] things, which in that went to Marcella's moment, what miles and fusion, the rock, jazz rock thing did.

Burn sugar was a repository of a lot of that. Let's say for example, You know, I just say that that women in Love was the moment when he said, I'm not just gonna be a consumer and observer around Black music. I'm gonna be a producer myself. Mm-hmm. . And if you want to tell the story of Greg, you have to kind of deal with burn sugar because it really was him like throwing his hat in the ring and not just standing back and critiquing people's hats.

You know what I mean?

Helga: I remember when he died that morning, Carl Hancock Rux called me. and I said, okay. And the first person I reached out to was you. Hmm? Yeah. Because of all the people I knew. Wouldn't be okay, it was you.

Arthur Jafa: Yeah, and I wasn't, okay. I was very much not Okay. That the proceeding two or three [00:31:00] weeks of Greg passing were very intense because, as I said, Aguire had opened, I had a lot of, uh, not yet processed feelings about it.

What it was, how it was being received, which I, as I said, I hadn't anticipated, I hadn't anticipated. Like recognizing that it was being very well received and that I was still, you know, on my run, I hadn't stumbled yet, and that maybe I was a success. Mm-hmm. and why did I feel so unsettled? And then, uh, Virgil Abloh, a good friend passed and I was very, very upset about that.

Virgil had just turned 40, and I remember saying this to Greg, you like warlords. You know, at some point you are a young warlord. Certain point, you are older warlord and you understand that nobody survives forever. And the people that you looked up to and who were like heroes and models, whether they be, I mean, it's more musicians than you can [00:32:00] mention, but than Toni Morrisons and uh, You know what I mean?

Like masters, I mean, well, we would term masters, but I remember saying to Toni Morrison, what are we gonna do now? Everywhere I look, the masters are down. And Tony just said it. You know what her hands out like, and here I am, which I was like, woo. not modest. You know what I mean? But how could you be modest in the face of that?

But I guess what I'm trying to get at is like, yeah,

Helga: that's on you too though, not to

Arthur Jafa: recognize. Yeah. And so the warlord thing to me is like, you realize that. , you do what you can do, and then when you look around and you see people coming up behind you who seem to be in. the tradition of what you wanna be in a nutrition.

Understand yourself as being in a traditional meaning, not just a creative, but a creative who understands that their creativity is bound up with a kind of epic struggle against white supremacy. And I would just say the negative retrograde. Forces in the world, you know what I mean? That you were an [00:33:00] agent of the emancipatory, not an agent of the whatever, the reverse, the enslaving impulse in human beings.

Mm-hmm. Um, which is not strictly speaking just a black and a white thing as we know, but this is certainly the manifestation of it here that we are familiar with. And so you start to see yourself a bit as a war Lord. So when you look back and you see somebody and you feel like, yeah, they got. . They got it.

They're doing it and they're taking it for, and Virgil was a person like that. He was a rare person who not only excelled, but he shared the blueprint. Mm-hmm. A lot of times when people excel, they don't share the blueprint, you know what I mean? They just get to where they are and you, we take 'em, say, well, we know we can get there, but they not sharing the map.

And Virgil was a person who almost compulsively I would just say super intentionally shared the blueprint. So when Virgil died, I was distraught. I was literally distraught.

Helga: And it's all happening in the same moment.

Arthur Jafa: I'm, that's what me and Greg talked about the [00:34:00] last two weeks of his life is Virgil. I remember calling Greg and said, man, we can't have nothing.

They won't let us have anything. You know what I mean? And I was like, why were you saying that? I mean, cuz it just seemed like in so many instances, anytime a Black person, like either you have the wherewithal but not the resources, or you have the, the resources, but you have no interest in the wherewithal.

Because in some ways it seems like oftentimes when Black people succeed in this context, a prerequisite for that succeeding, for being allowed to succeed is you have no interest in. Or inclination towrds or commitment to reproducing Blackness in the space that you're in. You're not, you know, it's like, yeah, we'll let you in, n***er, but we, you ain't bringing no more n***ers up in here with you.

And you can see it manifesting in so many different kinds of symbolic ways. Who people, pardon? With these kinds of things. Look, you love who you love. I'm not trying to critique who people love, but I'm just [00:35:00] saying there's a certain level of which structurally it is a real thing. I remember at a certain point I had this list of the 200 most successful people in the art world who are Black and without one or two exceptions, everybody had a white partner. It's not a critique of who you partner with. You love who you love. I love people who are, I've loved people who are not Black, so I'm not here talking about who you love and who you should love. I'm just saying structurally, if you make a list and you can only find one example on a list of a person partnering with a Black person, that's structural.

Helga: What do you think it says though, AJ?

Arthur Jafa: I mean, I think what it suggests is, like I said, we will allow individuals into this space, but only if they don't reproduce, only if they're, in some ways neutered. Even if that's only symbolic, you know? Only if we feel like if they were reproduce themselves, [00:36:00] they're not reproducing uncut Blackness.

And that's not just in ethos, it's not just in biology, it's just not in resources. I, I think that is the logic of white supremacy. Look, Black people, we don't situate being in the body in a way that white people or whiteness or white supremacy does. Meaning. For a Black person to have, like if one of your parents is Asian, that's just a Black person with an Asian parent.

That is not something non fully Black person that's just a Black person who has a Jewish parent or white parent. It ain't no thing for us. But on the other side of the equation, in terms of whiteness, it's like if you got one observable drop of blood and you then you're not white. White supremacy produces a different self-conception.

It's a very fragile self-conception cuz it's defined by what's not there, but not the whistles there. And that's an inherently unsustainable [00:37:00] position in the world. Cause the world is about bumping up against shit. I mean, this is why all this border madness and all this trying to protectorates and all this kind of stuff, it's because you can't win if your definition is, you have a mix with anybody.

See what I mean? The Black position, for better or worse, you don't become less Black cuz you mixed with something else. You just become Black with something else in it. But if you are white and you become mixed, then you are not white or you're less white or something like that. So it's a very fragile self-conception.

It's not a conception of them that anybody else imposed on them. It's their own self destructive for whatever reason's, conception. So, In the case of a Virgil, like for me, I was just distraught because I was like, this was a person who I felt like I can rest. If I need to rest, I'm not trying to rest, but if I need to rest, I know he got it.

He got it him and people like him. Got it. And so when he died, I was very [00:38:00] disturbed and upset. Like super upset. Like some things I wouldn't necessarily even wanna repeat in public that I felt like about what happened with Virgil. People would say paranoid things about what happened with Virgil, but will you

Helga: just say what happened with Virgil for the people

Arthur Jafa: who don't know?

Well, Virgil uh, had cancer, you know? Yeah. He had cancer. He was very young and he got cancer. Like Bob Marley got cancer and had people around him who he didn't share. It was only shared with a very small, right, small group of people. Virgil was a very brilliant person, so it doesn't surprise me, say for example, like a lot of people say, oh, he didn't share with many people.

Well, he sold off White to LMVH, which was his fashion label to a certain degree. Off White was Virgil. Virgil was off white. Off-White was Virgil. So like there's a certain kind of value that [00:39:00] it had because Virgil was part of it, and I'm not sure if they had known that he was sick, they would've bought it.

That's just me now. Yeah. So whatever you think about it, he secured the bag for his family. It's brilliant. It's, everything else he did was super brilliant. You know, after he passed a few months later, I was talking to a woman who's writing some things about him. I had written some things with him and she said, well, you know, as much as Virgil was loved, he wasn't necessarily loved in the fashion world in the same way that he was loved in general.

Meaning like a lot of individual people loved him, but the fashion world never embraced Virgil in a way because everybody could see that it was just a step for him. Like for most of the people in the fashion thing, that's it. It's, yeah, that's it. They arrived in Nirvana, but for Virgil, it could be like, I was ahead of, Louis Vuitton, and then I moved on and I'm not even doing fashion anymore.

Mm-hmm. , it was just a footnote. It was a chapter in my book, and that made people uneasy about [00:40:00] him. He had a nomadic quality. Anybody who knew him said he was doing the LMVH, but he was like DJing every, it was ama. It's like nobody quite understands how he would kept it up. Like I always say like, , he just never seemed weary.

He never seemed tired. He never allowed it to dictate his generosity with, you know, the people in his life, or pretty much almost anybody seemed like so, so when he passed, I was super distraught and I talked to Greg mostly, like anything that really troubled made me and Greg talked about it a lot. And in fact, I went to Chicago for Virgil's Memorial.

And uh, and I would say, Greg, hey, I'm going to do this. You know, they want me to say some words that is Memorial. And Greg said, you should write down like what you wanna say. Cause he knows me. That's like, I'm not a writer downer kind of person. I generally talk, you know, off the dome or something like that.

But he said, yeah, write it down because you have a lot of strong feelings. [00:41:00] And so I did like very atypically for me. People know me. I sat and wrote things down and I sent them to Greg because. Over the years, if it's something that I was super invested in, particularly if I wrote it, I would send it to him and just ask for notes or feedback, you know, and he didn't get back to me, which is very unusual cause anybody knows, Greg knows you could damn to call him anytime of night and he will wake up.

He just didn't seem to sleep or slept very lightly. and uh, so I just like, hmm, strange. But I'll just send it and I'm sure when I wake up in the morning, he would've gotten it cuz I texted it to him and he would've given me feedback or notes or something I got up that morning and no, you know, no texts or anything and, uh hmm.

Unusual but. I was focused on Virgil's Memorial. I read, you know, read my thing at Virgil's thing, had lunch with some friends in Chicago and then jumped back on the plane, was back in la, got in a little bit after midnight and about six in the morning, [00:42:00] I think Rachel called me and said, have you spoken to Brian, Greg's brother?

And I was like, no, why? And she said, call Brian. I tried to call Brian. I didn't get through to Brian. And then Craig Street called me and I said, Hey man, what's up? And he said, man, Tate's out. And I was like, huh? He said, and I, I littered, my legs collapsed. I was in the room out, my legs buckled onto me. I was just on the floor.

And so I was very, You know, I got your message. Just a lot of people calling me. I think because people knew how much he meant to me, like just straight up. At one point I was gonna say my soulmate, but I would just like the straight up love of my life. Like all the greats girlfriends used to laugh and say, well, I know me and you are like, you know me, and you are like semi-permanent, but you know, this n***a over here clearly is your partner or something.

You know what I mean? Uh, I mean, had I been gay, I guess we would've, we'd reacted on it, but [00:43:00] not at all. You know what I mean? So, um, we didn't hit it off right from the beginning, but we did eventually hit it off. But like, looking back now, you know, we had a 40 year run. It was all of my adult life, and a lot of people I know don't have friendships that deep or that last that long.

You know, sometimes you could have a friendship. It's deep like that, but maybe it didn't last so long. So I definitely feel very blessed to have had the run that we had. Uh, I miss him like every day. I mean, it made me think a lot about existence. Um, when he passed, um, uh, I told my son, I said, I've come to the conclusion that life as we understand it, is a narrowly dimensionalized sliver of existence.

Like if you sit down and you play chess or checkers, the board is flat and it's a 2D thing. But fundamentally what it is, is a symbolic enactment of human conflict, right? But it's a narrow narrowly [00:44:00] dimensionalized enactment of human conflict and, uh, opposing interests. . Right. And that's why we find chess or checkers maybe simply we find them interesting because they are like life in that way.

But I think life is like to existence as checkers is to life. And so I have no doubt that. When the game is over, I'm still in the game. He's not in the game, but I'm gonna like everybody check out of the game at some point that we'll be able to hang some more, you know? And I always think like, okay, Greg is in heaven now, or with the ancestors, the first thing he is gonna do is check in on Miss and Mrs. Tate. And then after that he gonna go find Jimmy. You know. That's the first thing that occurred to me. You know, he gonna go find Jimmy after that.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.