56 Years

(Dated music plays, almost backward, as if rewinding, then quiet.)

Julia Longoria: Vann, I was—I was so sorry to hear about your mom passing. Um, how—how are you holding up?

Vann R. Newkirk II: Uh, it’s, uh … it’s—it’s been a difficult couple of months.

Longoria: Can you—can you tell me about her? What—what was she like?

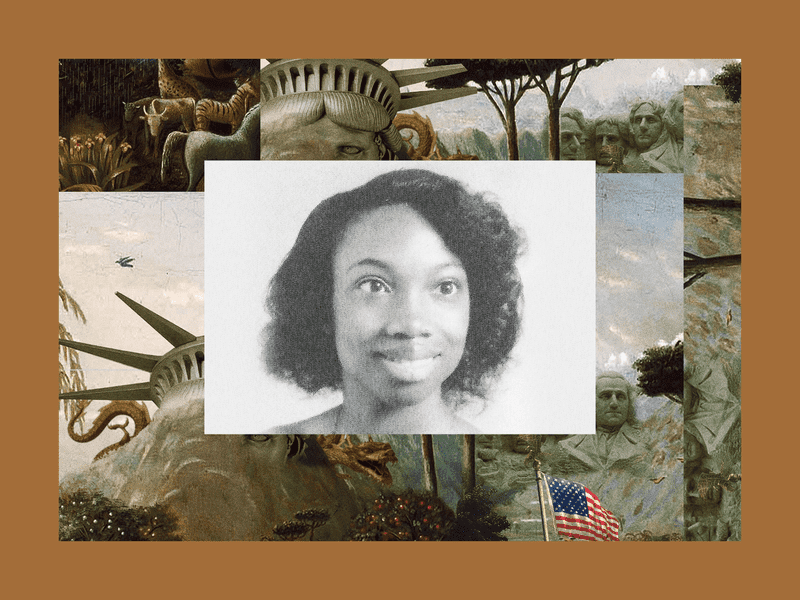

Newkirk: The first thing most people noticed about my mother was her eyes.

(Soft piano music plays, continuing under the narration.)

Newkirk: She had this, like, intense stare.

Longoria: Hm.

Newkirk: She was a teacher, and lots of kids would ask if my mom ever blinked. [Longoria laughs.] She never cursed. She was terrified of anything that did not have legs: snakes, slugs, worms. [Longoria laughs again.] The thing I think about a lot—and it’s a really weird, dumb thing to think about, but, you know, grief does really weird things to your brain—I think a lot about her hands. She and I have, like, strangely similar hands. Long, spindly fingers. Our knuckles are very prominent. It’s like branches on a tree, almost. That’s the first thing I think about when I think about her, uh, because it was such a reminder that she was me.

(Another moment of music.)

Longoria: The life of Marylin Newkirk ended on November 6, 2020, after a long battle with cancer. She was 56. She is survived by her husband, three siblings, and three kids, including her son Vann, who’s a senior editor at The Atlantic.

Newkirk: I’m my mom’s oldest child. I am, uh, required under law to only speak good things about my mother. (Longoria laughs.)

Longoria: When a life comes to an end, we—the ones who are left behind—we’re left with a story. Or really, a bunch of different stories. Like, for Vann, there were small stories about the way his mom looked …

Newkirk: … She had really plain attire. Jeans and a T-shirt …

Longoria: Or what she cared about …

Newkirk: Being involved in your church …

Longoria: How she treated people …

Newkirk: She was an incredibly patient woman …

Longoria: What she struggled with …

Newkirk: You could just see the stress, like, rising off her, like heat, almost.

Longoria: But when Vann took a minute to pull back, to really zoom out on a timeline of his mom’s life, he could see this bigger story—about the country she lived in.

Newkirk: One of the things I like to think about is the fact that, when she was born, it was by no means guaranteed that she would be granted the right to vote and that that right to vote would be protected.

Longoria: Looking back on her life, Vann sees a story about democracy. And it’s different than the one he was taught.

(The soft piano slowly fades out as Newkirk speaks, to be replaced with an airy synth sound.)

Newkirk: So, I mean, I was always taught that America was founded explicitly as a democracy. You know, you go to school and you’re taught that this was the biggest hit in global democracy since the Athenians, you know? But really, to me, I have been more and more convinced that the only true phase of what might even be somewhat called democracy in America has been America since the Voting Rights Act. And my mother has seen every single day of it.

(The airy synth plays up for a breath.)

Longoria: Vann says, contrary to what you might’ve been told, real democracy in America hasn’t been here that long. It’s only been here for 56 years.

This week, Vann Newkirk tells the short story of democracy by taking us through the life of the woman who saw the whole thing: his mom.

I’m Julia Longoria. This is The Experiment, a show about our unfinished country.

(A long beat with no narration, just music.)

Longoria: As Vann tells it, his mom was born just one year before our democracy started.

Newkirk: My mother was born in 1964. I understand that family storytelling is often, uh, embellished, so you have to work with me a little bit.

Longoria: (Chuckles lightly.) I know that all too well.

Newkirk: Uh, I have not yet gotten the fact-checkers on some of this. But, as the story goes, my mother was born in Greenwood, Mississippi. She went home in a cardboard box. That is the legend.

I believe it was probably one of those cardboard bassinets, which are not that uncommon. [Longoria laughs.] Um, but, yeah, you know? They were poor. And on the way home, you know, they drove past the headquarters of civil-rights organizations staging Freedom Summer.

Walter Cronkite: (Fades up.) This also will be known as the summer of civil rights because of the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project. (Fades out.)

Newkirk: It was, you know, one of the main flashpoints in the civil-rights movement, and they were staging it out of headquarters in Greenwood, Mississippi, where she was born.

Mississippi citizen 1: I walked in. He said, “What you want?” I said, “I want to register to vote.”

Newkirk: A lot of what they were trying to do was to register Black people to vote.

Bob Moses: … to send into Mississippi this summer upwards of 1,000 teachers, ministers, lawyers, and students from all around the country …

Newkirk: And they did that, in part, by bringing in lots and lots of volunteers—lots and lots of white volunteers—from around the country to come down to Mississippi.

White volunteer 1: And I hope we can reach the lives of as many people as possible …

White volunteer 2: … it may seem idealistic—the Constitution, the Bill of Rights—and I think it’s important for everybody to have these …

Newkirk: It was incredibly met with incredible amounts of violence.

(The sounds of activists being attacked, yelling, and gunfire.)

Mississippi citizen 2: So about two, three weeks after that, my house was firebombed.

Mississippi citizen 3: Her clothes had been torn. One of her eyes looked like blood.

Mississippi citizen 4: People should be expected to be beaten. They should expect, possibly, somebody to get killed.

Newkirk: She was born in the middle of all this! You know, a time when Greenwood was a very contentious place to live for Black people.

(The music goes quiet.)

Longoria: The demand from Black people was simple: They wanted the right to participate in the democracy that governed their lives.

In theory, this was a right they already had. We fought a war over it. We passed the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to secure it. (And, you know, the Nineteenth to add women.) On paper, all citizens had the right to vote regardless of race. But it hadn’t taken long for Southern states to find … work-arounds.

Newkirk: You start seeing what I like to call “the innovation lab of Jim Crow.”

Southern states essentially experimented with “What are the most effective ways we can kick Black people off while (a) minimizing the number of White folks we kick off, and (b) not triggering federal intervention.”

Longoria: Southern states passed poll taxes, which charged fees in order to vote. Literacy tests required voters be able to read. Grandfather clauses said a person could only vote if their grandfather could.

Newkirk: It’s not racist to say that you should only be able to vote if your grandfather voted. Is that racist? Hmm. You know, that was the kind of math and logic they were playing back then.

Longoria: And the math worked. The laws that were supposedly not about race ended up having a very clear racial effect.

Newkirk: So I know for a fact that when my mother was born, only 268 Black voters were registered in the county where she was born. So you think about a majority-Black county, over 40,000 people, and 268 of them are Black. That’s, uh, if that’s not, you know, essentially [A beat.] tyranny—

(The sounds of a protest. Yelling. Someone says, “Did you hear me?” in the commotion.)

Newkirk: —I don’t know what else you want to call it.

Longoria: This was the world that Marylin Newkirk was born into. But it wouldn’t stay that way for long.

(Music plays softly, like a lullaby, underneath the following clips.)

Fannie Lou Hamer: Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave? … But I am [A crowd echoes him.] somebody. [The crowd echoes again.] I may be poor … (Fades out.)

Martin Luther King Jr.: Even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with injustice …

Dave Dennis: Don’t bow down anymore! Hold your heads up. We want our freedom now … [A beat, then crying.] I’m tired of funerals. [A fist pounds the lectern.] Tired!

(A long moment of music before it fades out.)

President Lyndon B. Johnson: The command of the Constitution is plain. There is no moral issue. It is wrong, deadly wrong, to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country. (Applause.)

Longoria: After years of pressure from the civil-rights movement, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act in 1965. The law banned literacy tests and all the other ways states restricted Black people from voting.

And Vann says this moment in 1965—this is when democracy in the U.S. actually starts. Marylin Newkirk was a year old.

Newkirk: It’s really hard to overstate just how sudden and how almost miraculous this type of change was for people who had just never considered voting to be sort of within their menu of choices for living. To be able to go and say, “I want this person to be the president. I want this person to be the governor. I want this person to be our local representative.” That was—compared to the changes in American history—it was almost overnight.

(Low, solemn, droning piano plays.)

Newkirk: In the elections after ’65, those were the first time my grandparents and the vast majority of adults in my family on that side could vote.

Longoria: Really?

Newkirk: Yeah. My great-grandmother was a grandmother before she could vote. What a lot of people don’t really realize is that every Black person over the age of 76 has a story of when they voted for the first time under law.

(The piano drone develops into a melody.)

Longoria: If you think about it, the VRA was a radical piece of legislation—and radical not for what it did in that moment in 1965. It was radical because it sort of tried to predict the future, in a way.

It banned existing laws, but it also set up a whole system to prevent the future innovations of the innovation lab of Jim Crow. It did that by setting up a watchlist of states that had behaved badly. It said to those states, “From now on, the federal government is watching you. Before you pass any voting laws at all, you have to check with us first, to make sure the law is fair.”

It was because of that part of the law, Marylin Newkirk could expect that for her whole life, she would always be able to vote.

Newkirk: And really, when I started thinking about her life that way, everything made sense. You know, she was so concerned with her grandchildren being educated and being free, in a sense. And I had never really placed why that was so urgent to her. But I believe it was because the America she grew up in, to her, was always, in some sense, contingent, and always insecure, in a way.

Longoria: Turns out Marylin Newkirk was right to feel insecure. The most radical piece of the VRA was also the most fragile. That, after the break.

(The piano pedal lifts audibly. Then the break.)

(An electronic-music flourish.)

Newkirk: Soon as the Voting Rights Act was passed, there were people trying to overturn the Voting Rights Act. There were people who stake their entire livelihoods on doing it. There are consultants who built careers off of doing it.

Longoria: Despite attempts to bring it down, the VRA survived a bunch of different challenges over the years. More and more people voted. Congress reauthorized it. Courts reaffirmed it—until 2013.

Supreme Court announcer: We’ll hear arguments first this morning in Case 12-96, Shelby County v. Holder.

Longoria: Shelby County was in Alabama, one of the states that had come up with clever ways to keep Black people from voting before 1965. It was a place on the VRA’s watchlist that the feds were supposed to keep an eye on. If they wanted to make changes to their election laws, they had to get them precleared by the Justice Department or a federal court.

Shelby County got sick of being watched. Shelby County got sick of asking for permission. And so Shelby County sued the federal government.

Shelby County attorney: Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the Court …

Newkirk: Essentially, their case was one that had been built over the years by conservatives, which was: A lot of these portions of VRA nowadays are outdated. They’re outmoded. A lot of the teeth that we’ve given the VRA are simply not necessary in a world that’s past racism.

Shelby County attorney: So when I look at those statistics today, and look at what Alabama has in terms of Black registration and turnout, there’s no resemblance. We’re dealing with a completely changed situation—

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: You—you keep, you keep …

Longoria: Shelby County said, “Sure, some places used to discriminate, but not anymore. The list of bad counties and states you’re using is almost 50 years old. The country has changed.”

Chief Justice John Roberts: Thank you, counsel.

Shelby County attorney: Thank you.

Roberts: The case is submitted.

Longoria: And the majority of the court agreed.

Roberts: Any racial discrimination in voting is too much, but our country has changed in the past 50 years.

Longoria: Chief Justice Roberts, writing for the majority, essentially said, “The landscape of discrimination has changed. The geography is different. So that list the VRA created is outdated.”

Roberts: And therefore we have no choice but to find that it violates the Constitution.

Longoria: In effect, his decision meant Shelby County and places like it no longer had to ask for the feds’ permission to change their voting laws. Critics said the decision took out the heart of the VRA.

Newkirk: The most famous dissent to Roberts’s decision comes from now-deceased Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who says making a ruling to get rid of the thing that was stopping them from discriminating is essentially like having an umbrella and being in the rain and saying you don’t need the umbrella, because you’re not getting wet.

The VRA was a thing that was keeping states from discriminating, so changing it or dialing it back because they were not discriminating was a self-defeating premise. And she turned out to be right.

(Lush lo-fi music plays.)

Newkirk: The very next day, a bunch of states that were under the old preclearance formula start making new laws that make it harder to vote. So [Laughs.] North Carolina created a voter-ID law and began embarking on a set of voting laws that a federal court later said targeted Black voters with, quote, “surgical precision.” So they really just kind of got right back to it.

Longoria: The voting laws put in place in the years after the Shelby County decision—like voter-ID laws—seemed neutral at first glance. But critics argue that they have a racial effect, because people of color are less likely to have the right IDs. North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas, Iowa, and Mississippi, they all passed these strict voter ID laws. Some counties in Texas closed many polling locations. Georgia kicked people off the registration rolls, and made registering harder. Other states cut back on early voting. And through all of this, Vann’s mom was watching.

Newkirk: She would have her own little warnings, you know? She would say, “This looks like things we’ve seen before.” She kept up with it really closely on that level.

Longoria: Around that time, Vann’s mom got sick.

Newkirk: So, my mom was diagnosed with Stage 4 metastatic breast cancer in, uh, 2016. Um, you know, this was kind of like a war of attrition for her body. She fought it really aggressively, and she looked pretty good. But in 2019, it started coming back. So in 2020, she was doing the most aggressive, experimental stuff on the market—kind of what they call the “last-line treatments.” You know, in the height of a really uncertain election, she would call me. And she would say, “The thing you were warning about,” you know, “it’s happening.”

She would read in the morning about stuff that alarmed her. She always voted. And so she was really concerned about being able to cast her own vote.

Democracy Now! report: In Kentucky, the state slashed the number of polling places from 3,700 to just 170 …

The Global Herald report: In some areas, the large early turnout and technical glitches have led to long waiting lines and that has sparked a controversy in states like Georgia over whether officials are …

(A still, quiet note plays underneath the narration.)

Newkirk: And so—the week of the election, actually—uh, I got the call from my father that, uh, she would be in hospice shortly. So I flew to where she was in Nashville, Tennessee, the day after the election.

Um, I was with her Thursday night, and she passed away early on that Friday morning.

(A piano melody layers onto the quiet soundscape.)

Newkirk: She passed away in the middle of this sort of, like, weird two days after Election Day when they were refusing to call Georgia and Pennsylvania and everybody became mini–Nate Silvers. [Longoria chuckles lightly.]

Um, and everybody’s trying to do all this, you know, advanced game theory to figure out what happened in the election. And, you know, she followed the election so closely, and if she had just made it one more day, she would have been able to see the outcome. And she wasn’t able.

(A breath of quiet. Then the music softly reenters.)

Newkirk: So what I believe the election showed us was that, whatever we believe democracy to be in America, it is not ancient and it is not invincible. It is entirely contingent upon not just laws, but the interpretation of laws, and also contingent upon certain actors’ willingness to abide by laws and to uphold norms.

That is, you know, a lot of what we think democracy is, is fairy dust.

(The piano playing stops suddenly. The pedal lifts, then a few more notes play before quiet.)

Longoria: One of the things that’s grounded democracy for the last 56 years, that’s turned it from fairy dust into something concrete, is the Voting Rights Act. This year, there are two cases in the Supreme Court that could further limit the power of the feds to police voting laws. If that happens, it’ll take out the last major enforceable piece of the VRA.

Newkirk: You know, I’m thinking about the VRA as a wall, almost. A wall that if you undermine it in any way—it’s holding back a dam—and if you undermine that wall holding back a dam, if you take one brick out, then it makes the whole thing weaker, and eventually it’s going to collapse. And the future in which that collapses is one we go right back to 1964.

Longoria: What Vann’s arguing is that our entire democracy hinges on this one law. And laws are fragile. Laws have a life span. They’re supposed to be replaced as new generations of lawmakers write over them. But Vann says the right to vote—with no exceptions—is too important to be just a law. It needs to be something that lasts for more than a lifetime.

Newkirk: Most likely, my children, my descendants, my cousins, you know, people who I care about, they’re going to be living here. That’s—that’s how it’s going to be. So, for me, if I’m looking at the way, the most surefire ways, to make that living here bearable and free, as free as possible, despite being highly unlikely, my analysis is that an amendment is the only way to ensure that.

So I think we’ve got to look at the Constitution. I think we need the Constitution to say that, without reservation, everybody over 18 should be able to vote and, you know, should be automatically registered to vote. And so that would essentially cut off a good majority of the tools that people are currently using to stop them from voting.

If we make a constitutional requirement that all voting laws, if they make it harder to vote, have to justify why they do that, and the national default position is toward making it easier to vote and spreading the vote, then we cut off the oxygen to most of the other tools too. And I think it’s time to look at the Constitution and say, “Why don’t we have that? Why is the default in America a rather onerous registration process? Why can’t people with felonies vote? What’s the reason?”

I think once we start asking these questions, it becomes clear that the actual Constitution is one of the main things in the way here.

Uh, and that if we want a democracy, we gotta make it a democracy.

(Distant piano music plays, almost inaudibly.)

Longoria: What does your mom think about this country?

Newkirk: So … she wasn’t, you know—my mom was not an activist, per se. She thought that we should do what you need to do in order to keep your job and, you know, provide for your kids and your family.

But I think she believed, you know, [Laughs.] she—she believed that if we were vigilant, and if we cared for our communities as we cared for our own children, that we could make it.

Longoria: Do you think you believe in the same way she did?

Newkirk: (Takes a breath.) I hope that one day I will believe the same thing, you know? So, I mean … [Breathes deeply.] a country that produces a person like my mother, I think, is one where you—you have to retain some hope in its ability to be good and worthy. The fact that, you know, a woman who was born in a county where just over 200 people like her were able to vote, that she could go teach integrated schools, that she could go and be such a pillar, that she could live a life where she could expect certain things and where she would die believing that her grandchildren might have those things—those are things that, you know, you have to have some type of hope or belief in a place like that.

But also, you know, I think the course of her life should always remind us about how fragile everything is. Fifty-six years is not a long time. This phase of history is something that is constantly being negotiated, renegotiated.

(Wistful flute music plays over a droning chord.)

Newkirk: And if we are not vigilant, if we don’t have the same kind of work ethic, and we aren’t looking to preserve things for posterity, you know, I think it could easily slip through our fingers. And so that’s what I think about when I think about her life.

(The music plays up, interspersed with the trill of a bird call.)

Matt Collette: This episode was produced by Julia Longoria, Alvin Melathe, and Gabrielle Berbey, with editing by Tracie Hunte and Katherine Wells. Sound design by David Herman. Fact-check by Will Gordon. Our team also includes Emily Botein, Natalia Ramirez, and me, Matt Collette. Music by Tasty Morsels. This conversation was based on an essay Vann Newkirk wrote for The Atlantic’s new series “Inheritance,” a project about American history, Black life, and the resilience of memory. Find it online at www.theatlantic.com/inheritance. If you’re enjoying this podcast, spread the word: Rate The Experiment on Apple Podcasts, and share this episode with a friend.

The Experiment is a co-production of The Atlantic and WNYC Studios. Thank you for listening.

(More music for a bit, then silence.)

Copyright © 2021 The Atlantic and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.