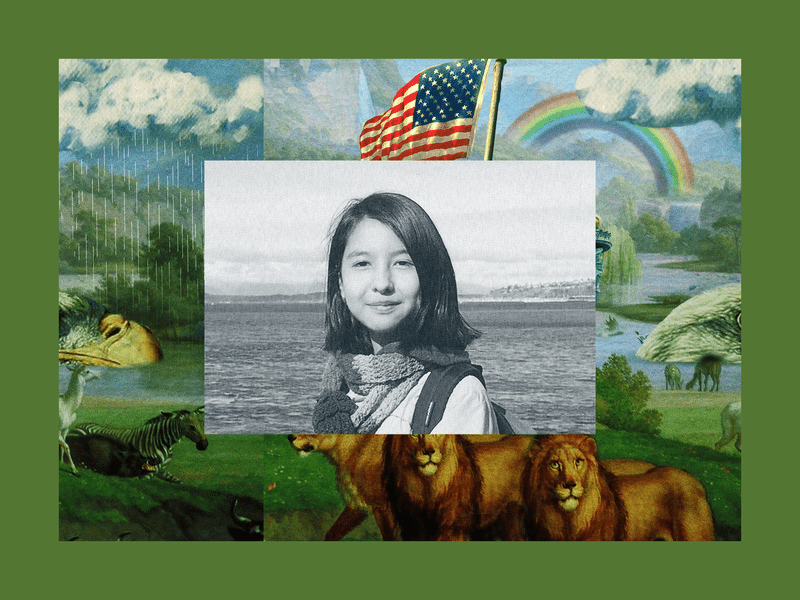

Teenage Life After Genocide

( Tahir Hamut Izgil )

(A heavy, low, roiling sound ever so slowly crescendos, up and up, and ends when a brief blip plays.)

Natalia Ramirez: Okay! Good morning! Um, so are you with a lot of family right now?

Aséna Tahir Izgil: (Laughs.) Yes!

Ramirez: (Lightly, also laughing.) Yes? How many people?

Aséna: So there is five people in my family.

Ramirez: Okay, cool. And, um …

Aséna: This is, like, the basic question I learned when I learned English with my teacher. (Chuckles.)

Ramirez: Oh yeah? Really? (Laughs.)

Julia Longoria: What you’re hearing is a mic check between producer Natalia Ramirez and our guest, a new young immigrant to the U.S.

Aséna: I remember my favorite phrase in, like, whole English language was “I don’t know.” (Both laughs.)

Ramirez: Why was that your favorite?

Aséna: Because it just avoid me from a lot of troubles. Like, my teacher asked me, like, complicated questions, and I’d just say, “I don’t know.” And then it’s done! So I still love it to this day. (Both laugh.)

Ramirez: Okay, perfect! Now you can stop recording.

(The blip from before sounds again.)

Longoria: So when I finally sat down to talk to her—

Longoria: You can go ahead and click Record.

(The blip.)

Aséna: Okay!

Um, hello! My name is Aséna.

Longoria: I first asked Aséna Tahir Izgil, 19 years old, about the things she did not know when she first got here from China four years ago.

(A slow but steady cushion of sound—a plodding percussion line, a jazzy synthesizer—lazily plays underneath the conversation.)

Aséna: I didn’t know what cafeteria means. It was, like, right before lunch, and the teacher was like, “Okay, kids, let’s go to cafeteria and eat your lunch!” And I was like, “What the hell is cafeteria?” [Both chuckle.] Sounds so fancy to me! [Both laugh.] You know, it’s like, uh, French or something.

Longoria: (Jokingly.) “Where are we going now?” Yeah!

Aséna: Yeah! Like, expensive, you know? It’s like an art gallery or something. [Both laugh.] Only thing that I learned from my British English that I learned from my teacher in a year was restroom.

Longoria: There were a lot of basic words she didn’t know. Like, instead of “restroom,” she would say “toilet.” Instead of “excuse me,” she’d say “pardon me.”

Aséna: So one day a girl in front of me—she turned her head back. She looked at me, and she’s like, “Hey.” I said, “Hey.” She said, “You know you sound like an old lady?” And I was like, “Really?” She said, “Yes.” I was like, “Okay.” (Laughs.)

Longoria: Aséna says she didn’t really mind being called an old lady—’cause a lot of times in class, she kinda feels like one.

Aséna: When I be friends with my same-age kids, I just feel like I’m their grandma.

Longoria: The main thing keeping Aséna from connecting to kids her own age isn’t the stuff she doesn’t know.

Aséna: The things they talk about is, like, TikTok, malls, games.

Longoria: It’s that she knows too much.

(The music changes tone. The percussion drops out, and a series of slow tones, almost like trumpets, play instead. The synthesizer is decidedly less jazzy, more spacious and empty. The whole of it feels more serious.)

Aséna: And then the things I think about, it was genocide, it was Uyghurs, it was international policies. All those, you know, like, annoying adult facts.

Longoria: Aséna knows these “annoying adult facts” because she’s Uyghur. She grew up in Urumqi, a part of Xinjiang, China, where over 12 million Muslims like her are now under extreme surveillance. Human-rights groups estimate that over a million have been detained in concentration camps over the past few years. And the U.S., Canada, and the Netherlands have officially called it a genocide.

(The music echoes and reverberates, then fades out.)

Longoria: Aséna and her family were able to escape four years ago.

Aséna: The whole thing just made me grow up so fast that I had to think a lot of things that, in my age, like, it doesn’t belong to my age.

(Airy, low woodwinds play through the crackle of gramophone static, looping quietly.)

Longoria: For years, I’ve been hearing stories about the Uyghurs in China, the ethnic minority group that’s been persecuted by the Chinese government. But very few Uyghurs have been able to leave China in the last few years, so it’s rare that we hear what is happening there firsthand, much less in English.

Aséna: It’s pretty much impossible to escape. I—I feel like I’m the only one who’s, like, the most recent here.

Longoria: So this week, the story of one young Uyghur: how she became old before her time in another country, and how she is now trying to make her way here, where no one her age seems to know the things that she does.

(The music plays up, surrounding, enveloping.)

Longoria: I’m Julia Longoria. This is The Experiment, a show about our unfinished country.

(Just as the background noise becomes overwhelming, it cuts out.)

Aséna: My name, Aséna, is a Turkish name. It’s a pretty common name in Turkey, according to my dad. It’s also a name of, like, a female wolf who’s, like, a mother of the whole Turkish people. So, at the time when he named me, he wanted me to remember that we are from Turkey.

Longoria: Aséna grew up among many Uyghurs in a part of China—Xinjiang—that used to be Turkish.

Aséna: We called Xinjiang “East Turkistan” here, just because it’s what it named before.

Longoria: But growing up in China, she didn’t know much about her own people.

Aséna: The history we learned is the Chinese history—their dynasties—I still love it ’til these days. I still watch movies about it; I still read books about it. It’s so beautiful. But they’ve never taught us about our own culture.

Longoria: In her classroom, in Urumqi—the capital of Xinjiang—where most of the kids were Uyghur, the only Uyghur history they got was a few paragraphs long.

Aséna: My Chinese textbook from first grade had, like, couple articles introducing Uyghurs. Basically what they introduced is: Our region is a pretty good region to grow fruits. We have a lot of good fruits and veggies. [Chuckles lightly.]

And the people there is friendly, optimistic. Every single person [Chuckles.] knows how to sing and dance. Little fairies, you know—like, a land of fruits and veggies!

That—that’s what they imagined.

And I was like, They don’t know anything about Uyghurs. We’re not like that. My dad doesn’t know how to dance. [Both laugh gently.] We don’t—we don’t dance around a fire. It’s like, we did, but, like, it’s a couple decades ago.

The understanding is not deep, and I’m pretty sure they don’t want it to be deep.

Longoria: Growing up surrounded by Uyghurs, this never really bothered Aséna very much. It was only when she left Urumqi.

Aséna: When you go to places that there’s only Han Chinese people that live, they literally just see you like a foreigner.

Longoria: She remembers one trip her family took to Beijing.

Aséna: We took a train, and it was, like, a pretty happy moment, ’cause I can eat whatever snack I want.

(Softly, a percussive melody plays underneath the dialogue.)

Longoria: What did you eat?

Aséna: Oh! Oh my god. I ate a lot of trash foods. [Both laugh.] Instant noodles. I ate all those, like, spicy little snacks. [Both laugh.] It’s been, like, a trash-food three days for me.

Longoria: Like a bender. (Laughs.)

Aséna: Yeah. Yeah! They basically don’t have any Halal foods in train. That’s why my mom just brought me a lot of snacks.

Longoria: Because your mom normally wants you to have Halal foods?

Aséna: Yeah, for sure. We’re Muslims. We have to eat Halal foods!

And then a pretty, really, really nice Chinese woman compliments me. [Laughs.] She’s like, “You’re so pretty!” That’s why I thought she’s nice. And then she told us that she didn’t even know the difference between, like, ethnic minorities in China. And the media taught them that the Uyghurs or other ethnic minorities is basically, like, I dunno how to say that word, but [Searching.] “brutal”? Yes, really brutal, religious, extreme people. But we seems good.

(A pause.)

Aséna: A lot of Chinese people had never traveled to Xinjiang, and they just believe the medias and the knowledge that they got from pretty old textbooks. They just describe us as, like, fruit-eating, dancing, singing, optimistic, brutal, religious, ethnic minority that, you know, like, dance around a fire. [Laughs.] That—that was their stereotype. And she told me that—pretty honest.

I wasn’t surprised. We just laugh. We don’t do anything else. It’s just—just insecurity. Just makes you feel like you don’t belong to this country. They literally, like, introducing you like an alien or something. (Laughs, but each subsequent laugh bears a growing nervousness, as if it’s a laugh of discomfort and not humor.)

(A beat.)

Aséna: We got used to it, to be honest. You got used to all these small discriminations, all those small stereotypes, all those small things—we got used to it.

At least I thought it was pretty normal back then. It—it hurts, but it’s like a little bit. It’s not much.

But the things they did afterwards was terrifying, and it’s basically a genocide.

(The music becomes more complex, adding in a swarm of strings whirring about.)

Longoria: The first big turning point for Uyghurs who had lived peacefully in China came when Aséna was just 8 years old.

Aséna: I was too little to understand what happened at that time.

Longoria: In June 2009, in a factory in eastern China, rumors flew around that Uyghur workers had raped two Han Chinese workers. As a result of these baseless rumors, Han workers lynched several Uyghur co-workers. This sparked protests in Urumqi, Aséna’s hometown. The protests were peaceful, but soon turned violent after police suppressed them.

Aséna: My mom and my grandma, they were going to a wedding at the exact day of July 5. And they left me and my sister to our, like, pretty close neighbor. So we were on the outside of our neighborhood and buying groceries in a—like, a small store on the roadside. But then, suddenly, a young guy from that store, he was, like, outside, and he just ran into the store and he was like, “Something bad happened over there.” That’s what he said. And then I saw it too. People literally screaming with sticks and stuff. They were like hitting each other. You can see it from really far. [A nervous chuckle.] It was really, really terrifying. It was like screamings and stuff. It was like a war—small war happening over there.

Longoria: At least 197 people were left dead from the violence.

Aséna: Couple hours later, I guess, my mom and my grandma came back. They saw the whole thing. They looked terrified, and they came back to our house and sit down and drink water and they just can’t speak for, like, a long time. And I was small, but I can feel, like, you know—it’s a pretty bad situation.

Longoria: The violence made international news and heralded a new era in the Chinese relationship to the Uyghur people. From then on, the government would watch them closely.

Longoria: Did you understand what was happening was because you were Uyghur—because it was about your identity?

Aséna: Yes.

Longoria: How did you know that?

Aséna: It was so obvious. [Laughs.] We knew just from our nature. It was just something that’s in your blood and your bones, and you know that they don’t like you and they discriminate you.

Longoria: Yeah. What—what do you mean that you know it in your bones? Like, what is that feeling?

(The whirring music has faded out slowly. Now, a plunking sound, like drops of water, sounds off solemnly in the background.)

Aséna: Mmm. [A pause.] It’s basically like you are a drop of oil, but you are in a cup of water. [Laughs.] You are, like, both liquids—both humans—but you can just never actually get into them. You can’t just put yourself into that water.

Longoria: After the violence of 2009, Aséna’s childhood was relatively peaceful. But in the background, clashes between Uyghurs and the government continued. And tension kept growing, mostly in subtle ways that Aséna never noticed—until 2017.

Aséna: The first sign of the things getting bad was they started to build brand-new, small police stations—like, a small box—in every 100 meters of our city.

It’s weird. I used to walk to school. It literally takes me, like, 10 minutes to go walk to my school. And in every quiet mornings that I walked by myself, I saw tanks with, like, five, six soldiers standing on a tank and looking at me when I walked past them. I knew things are really, really, really bad.

Longoria: What were people saying about this change?

Aséna: Let me tell you something. Um, you know the cable in the house?

Longoria: Mhm.

Aséna: They installed so many cameras. They did fingerprint checkers and all this stuff in every single part of our lives that a lot of Uyghurs start to believe that the cables have, like, chips or something that can record what we’re saying. So my dad and my mom, they didn’t believe it, but they still didn’t talk about politics at home.

You can tell how terrified we are. We couldn’t do anything. We couldn’t even talk about it. We were just, like, forced to get used to it. And no one could actually, like, stood up and say, “Hey, what you guys doing? We’re not prisoners.” But, like, no one. Not even the brave ones, not even the intellectuals—because they were all in camps.

Longoria: By 2017, Uyghurs had started to disappear, one by one. The Chinese government had taken them away to camps.

Aséna: Yeah. They first targeted the religious people and a lot of my dad’s religious friends got in there. If you look really religious, if you look really Uyghur—and especially when you were a male—they will definitely think you are suspicious.

Longoria: Suspicious? What is the suspicion? What are they suspecting?

Aséna: The suspecting is that you are a religious person and you are trying to divide the country. They started to put people inside those camps in the name of “studying.”

Longoria: The government called the camps “study centers.” And the official word from Beijing was that people were going there voluntarily, for reeducation.

Aséna: They said, “We are teaching them.” They said, “They have to learn Chinese language. They have to learn all the skills.” And then they’re gonna, like, put them back into society after they finished learning. That’s what they said—in the beginning.

Longoria: But as the months passed, people didn’t seem to be coming back. More and more people were carted away to camp.

Aséna: Intellectuals—my dad’s friends—they start to disappear.

Longoria: It’s estimated that more than 1 million Uyghurs have been put in these camps. Human-rights groups and several governments say that, at these camps, the Chinese government is forcibly sterilizing Uyghur women.

Aséna: I remember once, when I was in my classroom—we had cameras in classrooms, every single classrooms—one of my classmates started crying all of sudden. He said his dad was in camps. At that time, at least one relative, one friend from each family was in camps.

So the whole classroom just start to begin crying. And then my biology teacher—he stepped into classroom, he looked at us, and then he grabbed the blackboard wipe, and he covered the camera on the back door of our classroom.

He knew that the things he’s going to talk about is going to make him in a big trouble.

Longoria: What did he say?

Aséna: So he said, “Don’t cry. I know that the situation is bad, but you can’t let them see our tears.” He said, “You young people, you teenagers are the hope for Uyghurs. You guys can’t be freaked out. You guys have to stand up and be brave.” That’s what he said. And then, couple weeks later, he disappeared from school. And then we got the information that he is in a jail—like, in the camp.

Longoria: In a study camp.

Aséna: In the study camp. That’s my last time seeing him.

(A beat.)

Longoria: Watching their friends being taken to camp, Aséna and her family were terrified. And Aséna looked to her dad for answers about what was going on.

Aséna: My father is a poet and a writer and a film director—and my idol.

Longoria: Aséna’s father, Tahir Hamut Izgil, is a famous Uyghur poet—and an activist. He’d been politically active for most of his life. He helped organize hunger strikes and marches during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. And in 1996, after he applied to study abroad in Turkey, he was tortured and then imprisoned on charges of exposing state secrets. He spent three years in a forced-labor camp, where conditions were harsh and he lost 100 pounds. After that, he started over, building a career as a filmmaker and a poet in Xinjiang.

Aséna: So he’s, like, my idol. He’s—he’s really experienced, and it’s something I really respect.

Longoria: What is your favorite poem of your dad’s? Do you have a favorite one?

Aséna: I used to have one.

Longoria: Oh yeah? What was it?

Aséna: So I don’t know how did they translate it to English in exactly, like, uh, the words, but it’s called “Men ölgende.” If I translate it here, it’s like “When I Die.”

Longoria: Hmm. Do you remember it in—in Uyghur?

Aséna: Yes. Um …

[Aséna begins to recite the poem in Uyghur. The translation follows in parenthesis.]

Men ölgende (“When I Die”)

Men ölgende, bayriqingni chüshürme yérim, manga mensup tenha yoqilish. (“When I die, don’t fly your flag half-mast, it’s my destiny to disappear alone.”)

[Aséna pauses.]

… I forgot.

Longoria: Hmm. What does—what does that mean?

Aséna: It’s basically like, uh, he was saying, “When I die, don’t be sad and don’t lower your flags.” It’s basically like, uh, “I deserve a lonely death.” (Laughs.)

Longoria: (Laughs, maybe a little uncomfortably.) Oh goodness!

Aséna: I used to like it.

Longoria: What do you like about it?

Aséna: It’s just so lonely. You can feel the emotion. And I can tell my dad was lonely at that time. And I know it was, like, the hardest moments of his life, so I can feel the emotions.

Longoria: Aséna’s dad saw what was happening in Xinjiang and believed it wouldn’t be long before he, too, would be sent to the camps.

Aséna: He knows everything. He was so smart that he already smelled that the danger’s coming.

Longoria: So he started looking for ways to get his family out of the country—which proved very difficult. When he finally got a passport, they couldn’t get a visa. And when they got the visa ...

Aséna: They took our passports away. So he didn’t sleep for a whole night. And he searched online that “Which kind of illness that Chinese people will go treat in the United States.” It’s epilepsy. So my dad said, “I have epilepsy,” and he had to came to the United States to do it.

Longoria: They even got three medical professionals to help make the epilepsy look legit.

Aséna: You know, in China, um, you can basically do everything with money. [Laughs.] If you have money, you can do anything. You can fake anything.

Longoria: And then they had to wait.

Aséna: So, like, couple last months from our escape to the United States, my dad, he’s basically like a ghost. He was just, like, eating, and he just goes out to walk ’round and even run. He never exercised, but he just can’t relieve the emotion in his heart. It was—it was desperate. It just makes us so tired. When you are in that situation, you don’t even want to think anymore.

Longoria: Did you see him as your hero during this time—during that kind of desperate time?

Aséna: I thought I was—I was his hero. [Laughs, with sharp intakes of breath.] I tried my best to make him feel better. I was really afraid that his mental health—You know, in this situation, there’s no hero. It feels like the death is coming closer and closer to him every day, because every person that got into camps around him is related to him, and he knows that he can’t escape. I didn’t think, you know, he’s not brave. I didn’t think he’s not strong. I just—I feel sad for him. And I tried my best to make him feel better.

Longoria: During this time, all the family could do was wait.

Aséna: At that time, I hated the place. My walk in the streets, I hated. And I just can’t wait to escape. That was my thought. I looked at the soldiers, and I look at the street, and I look at the whole city that raised me, and I hated the city. And I—I was just—I just felt sad for them because I know the situation is going to get worse.

Longoria: Then, after months and months of trying to get out of the country, Aséna and her parents and her little sister made it to the airport.

(Busy background noise, then a beep—of the security points in the airport, maybe—signals a dreamy, light glockenspiel song, a lullaby.)

Aséna: When we, like, pass through the security points in the airport—and this whole process, you know, like, going from my house to the airport—it’s like spy movies you have. [Longoria laughs.]

I felt excited, to be honest. My parents were, like, freaked out. They’re afraid. But I was, like, excited, because I like airplanes. [Chuckles.] I was like, “Yeah! 16 hours of airplane!” [Longoria laughs again.]

But then, after a couple hours of excitement, um, there’s, like, an empty feeling in all of our hearts, I guess. It just feels like you escaped from your own—own homeland. You lived there—especially for my parents, they lived there for, like, 40, 45 years. And they’re, like, going to a new—brand-new country that they only saw in movies before, you know?

(The music quiets.)

Aséna: So it just—you don’t know what to do. It’s just—it’s unknown. The future’s unknown. And it was a complicated feeling. We just sat there, like, quietly, for, like, hours thinking about our own future. Except my sister! She was sleeping. (Both laugh.)

(As the plane in the story begins to land, the music picks back up, whirling and twisting like butterflies in Aséna’s stomach, distorted and weird.)

Aséna: It was all those unknown, worried, panic feelings. And then, when I stepped out of the plane, and I see all those people, it’s just disappeared [A beat.] at one single moment.

(The whirlwind of noise cuts out suddenly, making way for a twittering bird, the sounds of the commotion of bodies. After a second, an eruption: animals and wind and traffic, people talking and the movement of feet, a melody weaving through it all, monumental and entirely overwhelming.)

Aséna: It was like I’m in a garden. I still dream about it sometimes, in my dreams.

Longoria: Really?

Aséna: Yeah!

Longoria: What does it—what do you dream about?

Aséna: Like, when I see, like, a bunch of Americans. They’re so colorful. All the ethnicities you can find in the world. [Laughs.] All the colors of hairs, skins, all the heights, all the weights. All the genders, colors, all the weird clothings. [Both laugh.] Difference, it’s just make it so beautiful.

It feels like I’m in a garden with all the colors of flowers. [Laughs.] When I see all those people, I feel like, Hey, you see all those colored people here. They looked like they’re fine; they’re living here. And they’re fine all together. So I guess I’m going to be fit in here too.

(The cacophony of life—of Aséna’s dream—plays for a moment. A lullaby lilts its way through the animals. The sound is so full that it feels as though it might burst. After a long moment, the sounds quiet, leaving only the melody of the lullaby.)

Aséna: Oh, my brother is crying. Can you hear him or no?

Longoria: Oh, a little bit. Yeah. Is he doing okay?

Aséna: Okay. I should—I should change my location. [A beat.] Oop! (The blip of the recording ending.)

Longoria: Aséna starts a new life, after the break.

(The break.)

(As the break ends, the melody of the lullaby reprises for a moment. Then, the blip.)

Aséna: Hold on. Okay, I’m back. Hello?

Longoria: I’m Julia Longoria. This is The Experiment, and we’re back with the story of Aséna Tahir Izgil.

Aséna: Hello?

Longoria: Hi! We lost you. (Chuckles.)

Aséna: (Laughing.) Yeah, I changed my location. Just the way my brother’s—

Longoria: Is everything okay?

Aséna: Yeah, yeah, yeah. He was just crying downstairs.

Longoria: Back in 2017, Aséna’s father’s plan to escape finally worked. She, her parents, and her sister finally boarded a plane to the United States.

Aséna: And I got here, stepped out of the airplane, and I saw the Starbucks. [Longoria chuckles.]

The Starbucks looked amazing. It smells amazing. It smells so expensive. [Both laugh.] It smells fancy. [Longoria bursts out.] So I went in there, and I bought a cup of coffee. It’s, like, a random ordinary coffee, nothing fancy. And I drink it. I don’t like coffee. I don’t like coffee ’til now! But that coffee tastes so good. It tastes, like, upper-class. [Both laugh.]

I feel like I’m rich now, you know? I feel like I can go back to my class and tell them that I had this Starbucks, and they must be jealous. That was my first thought. I was happy—excited for a couple minutes—thinking about, you know, like, the images of going back and tell them I drink Starbucks.

And then, all of sudden, I realized it’s impossible. And then I realized, I had the Starbucks, and I might have it like every single day of my life for next years, but they can’t.

So, I just—I—I was not happy anymore. Every time, the feel of guiltiness is that when you try something new and when you eat something good, the only thing is, after, like, short terms of happiness, the thing left in your mind is, They should try this too.

(A single violin plays as if in an echoey chamber, lonely.)

Aséna: Like, why—why am I the one who is enjoying it? What—what did I do? I don’t deserve this, you know? I should stay with my—my people. I should stay with my relatives and I should stay with my classmates. And I don’t deserve this beautiful life here.

(Clanging, twisting, almost industrial bells chime in.)

Longoria: But slowly Aséna tried to adjust to life in the United States. She was the only one in her family who knew English, so she had to act as their translator, helping them find a new apartment, find the cheapest groceries—stuff normally adults would do—all while she tried to adjust to American high school.

(The music plays out.)

Aséna: I didn’t like the kids in my school. I thought they’re immature. I even blamed them for not knowing what’s happening in my homeland. I compared them to my classmates who have to see their parents in camps or in jails.

So I just kind of hate them too. I—I hate them being, like, so ignorant, not knowing what’s going on. Like, things are really bad in—in corners of the world, but you guys here just, like, doesn’t know anything and having a really, really good life that we can’t imagine.

Longoria: It’s like not knowing here is, like, this luxury. It’s, like, being spoiled to not know about these things happening.

Aséna: Yeah. When the kids in my classroom talks bad things about the government—the American society—I feel really angry. No, I was not born here, but I love this country more than anyone that’s in the classroom. They never know how lucky they are, and they never know how things can get really bad in other countries, but here they’re safe. They even have the freedom, you know, to talk bad things about the government and stuff we can’t even talk about in our own—own house. They can do it in classrooms, and they can debate about it. I felt like they don’t know how to appreciate the country.

But now I realize it’s a good thing.

Longoria: What do you mean?

Aséna: For the people to have thoughts, to have debates, to think in opposite views and not only just compliment the government and compliment society—especially for young people, I guess it’s a good thing. I mean, I can be the lover, you know? [Laughs.]

I can be the one who compliments every side and they can be the one, then, who can see the bad sides. And we can work together and make this place a better country.

But I still think they should appreciate it, you know? They should at least appreciate big soccer fields and the basketball fields. It’s expensive.

And the whole, like, American life feels like a dream for us. It was so unreal. I realized that, after escaping here, every single one in the family felt some sense of guiltiness.

Longoria: Is there another life you imagine for yourself that would take away the guilt? Like, what do you wish you could do?

Aséna: At the time, to be honest—it’s a pretty dark thought—but I wished I could die.

Die in, like, a way that everybody knows what’s going on in Xinjiang.

I just wanted to rescue my people.

Longoria: Like, you wished you could die and kind of save all of them from … ?

Aséna: Yes.

Longoria: … That pain?

Aséna: If I go back and died in a way that it’s beneficial for my people, I felt like this guiltiness will go away. (A breath.) That was my thought.

Longoria: Have your thoughts changed?

Aséna: Yes.

Aséna: One day, in February 2019, when I got back from school, sitting on a couch, and my mom said to me that she’s pregnant. I was, like, 18. And I’m 18, I’m going to have a baby brother. [Both laugh.] And I was shocked. [Both laugh even more.] I was, like—I was shocked! [Longoria keeps laughing.]

I’ve been through so much with my parents, you know? I’d survived, like, a genocide. So I was, like, sitting on the couch for, like, literally hours, like, thinking through in my mind.

Longoria: (Chuckling.) What did you say to your mom?

Aséna: I said, “No.” [Longoria cracks up.] I said, “Definitely no. No.”

But she obviously didn’t listen to me. And she was mad at me; I was mad at her. I was mad at her that she’s not responsible to herself and she tried to give birth in such an old age. I want my mom. I don’t want a new brother. That was my thought. And she was mad at me that I was so cold-blood that I didn’t want a baby.

So we had a couple of days of cold war. [Longoria laughs.] But then I had to go take an appointment for a doctor to go to ultrasound. I give up.

So I apologize, after thinking through it a couple of days. You know, it’s her choice. I can’t—I can’t change her decision. So I realized that we definitely need something that we can take care of and, you know, like, distract us from the emotions.

So I thought my brother was a good choice, and it ended up I was right. No one can think of anything [Laughs.] except, like, taking care of baby when they’re taking care of baby. It’s so distracting. [Longoria laughs.]

But when I take my baby brother to, like, playgrounds and stuff, everybody look at me, and I’m pretty sure they think I’m a teen mom. And I’ll accept it, you know? [Longoria laughs.]

I can’t die now! I have a baby. [They both laugh.]

I’m a teen mom. I have to take care of my baby. [Longoria cracks up.]

He basically saved us from our bad mental-health situation, because you can’t die, you know, with a baby. It’s—it’s—it’s not good! You have to live for them.

So you said, if my thoughts have changed. I’ll say now, like, it changed. I don’t want to go do a pointless death. I want to spread the story. I want to be successful, as my biology teacher said. It might not helpful if I was back in China, but now I’m here, and I hope—I hope it works. [Both laugh gently.]

I hope I can do the things that my biology teacher said, you know?

Longoria: Be the—the hope of the Uyghur people?

Aséna: Yeah, yeah. Be the hope of the Uyghur people [Both laugh.] by teaching my brother stuff [Both laugh harder.], always remembering the responsibility, and [Sighing.] always keep this guilty feeling.

Longoria: Always keep it?

Aséna: Yeah, always keep it. I don’t wanna—I don’t wanna forget it. It’s painful, but I think I have to keep it. Mmm.

I want to—I want to feel guilt. I wanna—I wanna help my people. I want to always remember this. But I also want to enjoy my own life, you know?

(A new lullaby—this one heavier, playing in a void but resonating so it feels less lonely, more cocoonlike—begins. After a long moment, as Longoria starts to speak, it fades out.)

Longoria: (Speaking softly and seriously.) Hmm. It’s so interesting, like, just listening [Longoria sighs.]—it’s just really powerful, and I feel really grateful that you’re sharing so much with me.

And my parents were actually born in Cuba. Um, they came from Communist government there. And reading your dad’s work and listening to you talk, it actually reminds me a lot of stories my family’s told, you know? About the experience of being under a Communist government: the fear, the mistrust, these neighborhood committees that would “check up” on each other.

My grandfather always talked about how he wished he had stayed, how he wished he could have made the country better instead of, like, coming to this country. It’s like this country kind of had it figured out in his mind, you know? (Laughs lightly.)

Aséna: Yeah.

Longoria: America had it figured out. And so, you know, he wished that he had been brave enough to do something in Cuba, you know? And it’s so interesting, ’cause, you know, I dunno—I guess, like, if you have a daughter, that would be my generation, you were actually the same age that my dad was when he came. And I’m American now, so you adjust to a new country. You let go of the guilt. You just look forward. ’Cause I guess that’s all you can do.

I don’t really have a point, but [Both laugh lightly.] that was my—that was—that’s what I’ve been thinking about. [Inhaling sharply.] Um …

Aséna: Yeah.

Longoria: Do you have hopes for, like, your—I don’t know—if you have [Laughs.] a daughter, what you would want, as she lives in this country?

Aséna: My brother—when my brother born …

Longoria: Hmm.

Aséna: We have, like, a special event. So, basically what they do is, like, they put him in a bathtub and then, like, little kids come over. Then they pour, like, one spoon of water on him and then saying good wishes. My parents invited, like, five, six kids around—like, Uyghur kids, you know? [Chuckles.]

And then they poured the water, and they tell him to be rich, to be a scientist. [Both laugh.] They said all kinds of successful lives—to be a doctor—all kinds of stuff. And then, when it’s my turn, I—I grab a spoon of water, and I pour it on him, and I said, “I hope you become a free person.”

(A beat.)

Aséna: That was my thought. I just want him to have, like, a freedom. My dad struggled almost his whole life, looking for freedom. And he finally got it, and he’s, like, 50s. And I hope my brother, he can be free forever. But I know it’s hard for him to escape this identity as Uyghur.

I think about it all the time, that if it’s fair, like—fair to, you know, like, let him get all those memories and give him this, like, this, um, hard responsibility. Like, give him this identity—the whole Uyghur identity. I don’t know if it’s fair for him, but—

Longoria: (Softly.) What do you mean?

Aséna: Like, um, I dunno. I just want him to have the choice. I just want him to have the choice—to choose if he wants to be Uyghur. Choose if he wants to, you know, get all those genocide, all those bad things from—from our memories.

Longoria: You want to give them the luxury of not knowing?

Aséna: Yeah. But, like I mentioned, it’s in our bones and bloods. You can’t escape it. Then I realized he has to—he has to be a Uyghur. His name is Tarim. My dad gave him this name. And Tarim is, like, a mother river of our homeland.

Longoria: Is a what?

Aséna: Is like a mother river? So basically it’s, like, the river that raised us. That’s what Uyghurs say.

Longoria: “The river that raised us”?

Aséna: Yeah. It’s a big river, you know, in Xinjiang, and, basically, Uyghurs lived in Xinjiang because of that river, I guess. All the civilization started with the water. (Laughs quietly.)

Longoria: Hm, yeah.

Aséna: So, yeah, his name is Tarim. And my dad and my mom, they don’t want him to forget he’s Uyghur.

And they have hopes for him, not—to at least not forget where he’s from.

I feel like he’s going to struggle a lot in future, and I have to help him. [Both laugh.]

He’s going to be like, “What the hell is Uyghur?” And I’m gonna explain to him. And he’s like, “Okay, what does it look like?” [Longoria starts to laugh.] I have to tell him that we dance, we sing, you know, around the fire. [Longoria laughs even more, a laugh that sounds like a release.] We have veggies and fruits! [Both crack up laughing.]

Yeah. I have to buy that textbook from eBay or something, if they sell it here. You know, I have to show him, like, this is Uyghurs!

(Light music, funky and ethereal, plays clearly for a moment, then descends into a fog and fades out.)

Aséna: Okay. Uh, my dad is out here. I guess our time’s up. Do you want to talk to him, though? He can say hi.

Longoria: Yeah! I would love to say hi.

Aséna: Okay. Baba! [Speaks to her father, Tahir, in Uyghur. Translations are provided in parentheses.]

Dada, kéling, mawu mukhbirning siz bilen körüshküsi barken. (“Dad, could you come over here? This reporter wants to talk with you.”)

[In English, to Longoria.] My dad loves interviewers.

[The sounds of shuffling and creaking as Tahir settles in. Then, in Uyghur, Aséna speaks to her father.] Mana. (“Here.”)

[In English, to Longoria.] Okay, you can say hello, Julia.

Tahir Hamut Izgil: Hello, this is Tahir!

Longoria: Hi! Hi, Tahir! This is Julia Longoria from The Atlantic. Thank you so much, um, for—

Tahir: Hi, Julia!

Longoria: Yeah, it’s so nice to meet you!

Tahir: Nice to meet you too.

Longoria: Well, your daughter is really incredible. She’s been telling me all about her experience, and she’s—I know you know she’s wise beyond her years. It’s been such a privilege to talk to her. So, um, you raised a pretty incredible person.

(Aséna translates for her father.)

Aséna: (In Uyghur.) Méni bek yaxshiken deydu. (“She’s saying nice things about me.”) (Both chuckle.)

(Aséna turns back to Longoria.)

Aséna: I translate for him that “I’m the best! I’m the best!”! (Both Aséna and Longoria laugh.)

Longoria: Um, would you ask him if he could remember any of that poem? Maybe you could start it off for him, and maybe it’ll jog his memory?

Aséna: Yeah!

(Aséna translates the request for her father.)

Aséna: (In Uyghur.) Dada, birer shé’ir ésingizde barmu? Shé’irdin birini dep béring, bizning mawu némige salidighan’gha. (“Hey, Dad, is there a poem you know by heart? Could you recite a poem for us, to put in?”)

Tahir: (In Uyghur.) “Aséna” dégen shé’ir? (“How about my poem ‘Aséna’?”)

Aséna: (Over the sounds of a car beeping and signaling.) Oh, yes! He wrote a poem with my name. It’s called “Aséna.”

Longoria: Oh yeah?

Aséna: Yeah.

Longoria: Would he … ?

Aséna: I forgot about that poem. Totally.

Longoria: (Laughs.) Would he—would he recite it?

(Aséna once again translates the request.)

Aséna: Ésingizde barmu u shé’ir? (“Do you know that poem by memory?”)

Tahir: Tordila bar u shé’ir. (“That poem’s available on the internet.”)

Aséna: Yadlap bérelemsiz? Siz oqup bersingiz podcastning akhirida chiqidiken. (“Could you recite it from memory? If you recite it, it’ll be included at the end of the podcast.”)

Tahir: Men hazir oqup bersemmu? (“Recite it right now?”)

Aséna: He’e. (“Yes.”)

Tahir: U shé’ir hazir yénimda yoq. (“I don’t have that poem with me at the moment.”)

(The two finish talking.)

Aséna: Okay, so we’re gonna—my dad said it’s totally fine for him to recite it, So later today we’re going to do it.

Longoria: We’ll do it later? Okay. Great. All right, well, enjoy your vacation. Thank you so much!

Aséna: Thank you!

Longoria: We’ll talk later. Bye. Bye.

Aséna: Bye. (The blip as the recording ends.)

(Over a lilting piano melody, Tahir reads the Uyghur poem he named after his daughter, “Aséna.” Each stanza that starts with “She” can be heard like a pause in the Uyghur.)

Tahir:

Aséna

A piece of my flesh

torn away.

A piece of my bone

broken off.

A piece of my soul

remade.

A piece of my thought

set free.

In her thin hands

the lines of time grow long.

In her black eyes

float the truths of stone tablets.

Round her slender neck

a dusky hair lies knotted.

On her dark skin

the map of fruit is drawn.

She

is a raindrop on my cheek, translucent

as the future I can’t see.

She

is a knot that need not be untied

like the formula my blood traced from the sky,

an omen trickling from history.

She

kisses the stone on my grave

that holds down my corpse

and entrusts me to it.

She

is a luckless spell

who made me a creator

and carried on my creation.

She is my daughter.

(The poem ends. The piano continues to play after Tahir reads the last line. It continues even as the credits begin.)

Tracie Hunte: This episode was produced by Julia Longoria, with help from Gabrielle Berbey and editing by Katherine Wells and Emily Botein.

Fact-check by Yvonne Rolzhausen. Sound design by David Herman, with additional engineering by Joe Plourde. Translations by Joshua L. Freeman. Music by Tasty Morsels.

Our team also includes Natalia Ramirez and me, Tracie Hunte.

You can read work by Aséna’s father, the poet Tahir Hamut Izgil, titled “One by One, My Friends Were Sent to the Camps” and more on the Uyghurs in China on our website, www.theatlantic.com/experiment.

If you’re enjoying this podcast, please spread the word: Rate and review us on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen.

The Experiment is a co-production of The Atlantic and WNYC Studios. Thank you for listening.

(Slowly, but with a certainty, the piano’s quiet melody comes to a halt.)

Copyright © 2022 The Atlantic and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.