Tanzina Vega: I'm Tanzina Vega, and this is The Takeaway. Sunday marked the 30th anniversary of the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, also called the ADA.

[applause]

President George H. W. Bush: And this is-- this is indeed an incredible day, especially for the thousands of people across the nation who have given so much of their time, their vision and their courage to see this act become a reality.

Tanzina: That was President George H. W. Bush at the signing of the ADA which prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in the United States, and that includes at the ballot box, but while the ADA intended to make polling places more accessible to people with disabilities, they still remain largely inaccessible today. According to the government accountability office, just 40% of US polling places were accessible during the 2016 election, and access to polling locations is just one of several challenges faced by people with disabilities when it comes to voting.

For more on this, we turn to Rebecca Cokley, the director of the Disability Justice Initiative at the Progressive Center for American Progress. Rebecca, thanks for joining us.

Rebecca Cokley: Thank you for having me here, Tanzina.

Tanzina: Let's start with a basic definition of disability today. How do we define it?

Rebecca: So according to the ADA, a disability is a mental or a physical impairment that impacts an activity of daily living. Our forefathers or our elders or whatever you'd like to call them, we're very intentional about not including a checklist about what is and isn't disabled. Um, you know, and I think that's very important because if you think about it back in 1990 when they wrote the law, it was on the heels of AIDS and HIV's massive outbreak in the 1980s. We're also talking about a generation of legislators and advocates that came out of the Vietnam era, people with both physical and mental trauma as a result of-of their time in military service.

So disability was not just white dudes in wheelchairs, even though that's what we see on our parking signs, um, disability was mental health, disability was chronic, uh, was and is chronic illness, you know. And if you think about it today, if they hadn't have been that flexible in terms of the actual definition of disability, it wouldn't include kids in Flint who are drinking leaded water after all this time, it wouldn't include students in Compton, California, who sued to be able to receive special education services citing that poverty in effect had made them disabled, and it wouldn't include people today who are living with a long-term impact of the coronavirus.

Tanzina: Let's talk a little bit about where we are in terms of access to voting. Uh, we are in a contentious, um, election season, probably one of the most significant elections that many of us have witnessed in our lifetime will be happening in November. So tell us before the ADA, what did voting rights and access look like for people with disabilities?

Rebecca: It was very much a hodgepodge. I mean, I remember going to vote with my father who was a wheelchair user when I was a small child, and I remember us having to sit in our car and wait for someone. I had to run in actually, to the polling place, which was at a church, and let's remember that churches are actually exempted from the ADA, which is really problematic when it comes to voting because churches are one of the most popular voting sites.

So, I remember running into this church and asking them to bring out a ballot to my dad who was sitting in his van, because there was no curb cut for him to bring his wheelchair up. There were three steps outside of the church. There was no ramp down to where people were actually voting inside the church. And so quite literally, a poll worker just came out and handed my dad his ballot and like sat there while my dad voted. And that's actually a very common story for a lot of people with disabilities, or you know, it was-- we've heard stories of people with disabilities who've arrived at polls and been told that-that they assumed, they, meaning the poll workers assumed that disabled people couldn't vote.

Tanzina: Rebecca, tell us about what are called incompetency laws and how those affect the right to vote for some people with disabilities.

Rebecca: So, incompetency laws vary across the nation and they're laws that are put in place. They're also typically called guardianship laws. And these are laws that are-- specifically target largely people with mental illness, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and they are typically put into place as somebody transitions from special education to whatever comes next. Parents are largely encouraged to apply for guardianship for their loved one under the premise that should they not, they'll have no say in any of the decision making as it relates to that person, their education, or their care.

However, this is simply not the case. But one of the things that we have seen as a result of this, is tens of thousands of disenfranchised voters around the country depending on what a state's given definition is. Um, I think probably one of the best cited by the disability community but least known by mainstream society is Britney Spears. Britney Spears is not able to vote in this current election.

Tanzina: And she's not able to vote because?

Rebecca: Britney's father and her business manager have her under a guardianship plan, and so because Britney is under guardianship, she is not able to cast a vote in this election.

Tanzina: Rebecca, how have these incompetency laws been justified?

Rebecca: They've really been justified because our nation still largely operates off of a framework of paternalism when it comes to people with disabilities. The ADA is 30-years-old and while it is middle age, you can say in some ways it is sort of having a midlife crisis at the moment. But what we've seen as it relates to the guardianship statutes, is that people really apply for these for their loved ones out of thinking, "Well, if I don't do this, who's going to have a say in the-person-that-I-love's healthcare? Who's gonna have a say in their financial obligations?" Or, you know, "What if they are the target of fraudsters?"

And so I think there's a real opportunity here to broaden the conversation and, you know, share with folks that are listening, that this isn't the only option. I think it's also important to note that the number one reason that people with disabilities challenge their status, they challenge their "guardians" in court is to vote. We hear that time and time again from people with intellectual and developmental disabilities and people with mental illness who want to be able to vote, but find that they're not eligible to vote under their state statute.

Tanzina: How has, uh, coronavirus affected, uh, access for people with disabilities so far?

Rebecca: Well, we know that roughly one third of the individuals that have died of coronavirus are people in nursing home settings. And while society likes to put out the notion that it's only seniors in nursing homes, the reality is that there's a large number of people with disabilities, including children with disabilities in nursing homes around this country. Also, um, people with underlying conditions count as people with disabilities under the ADA. We know that these folks often are also individuals of color, so we're also talking about issues of systemic racism in the medical field when it comes to this. And so when we're seeing who's dying, it's largely people of color with disabilities.

Tanzina: Like I mentioned, we have a very important election coming up, what should we expect at the polls come November for compliance with disability, uh, regulations so that people with disabilities can actually exercise their right to vote?

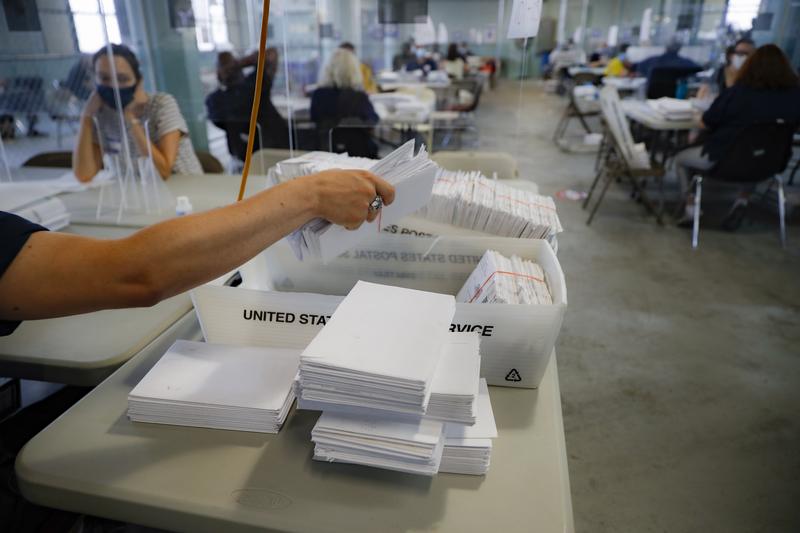

Rebecca: Well, frankly, I'm not holding my breath. One of the biggest challenges with the data that we continue to see out of the GAO is that that number, that 60% of polling places are still inaccessible in one way, shape or form has held steady over the last three presidential cycles. I think given the circumstances of the coronavirus, the best case scenario is a mix of universal vote by mail so everyone would receive a ballot as well as limited in-person options, because let's be real, even vote by mail is not accessible for all people and so we still need in-person options.

And so I think that the best case scenario is a blending of early voting and making national voting day a holiday, but that must be done with early voting or we'll actually see a disproportionate impact on disabled senior and low-income voters.

Tanzina: Rebecca Cokley is the director of the Disability Justice Initiative at the Center for American Progress. Rebecca, thanks so much.

Rebecca: Thank you so much for having me.

Tanzina: Have you or someone you know been affected by the Americans with Disabilities Act? What has it meant for you and your life? Leave us a message at 877-869-8253.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.